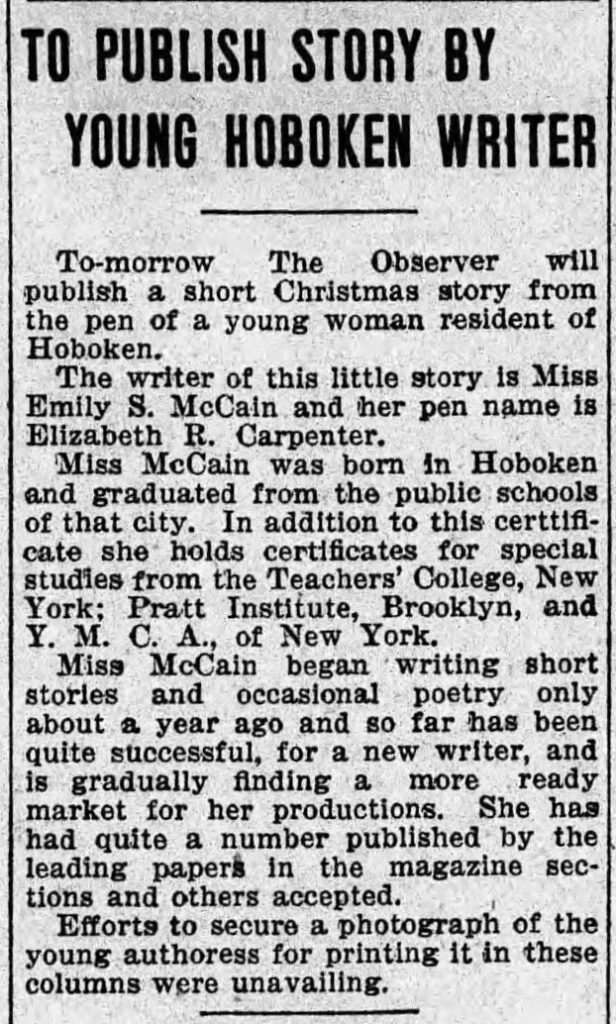

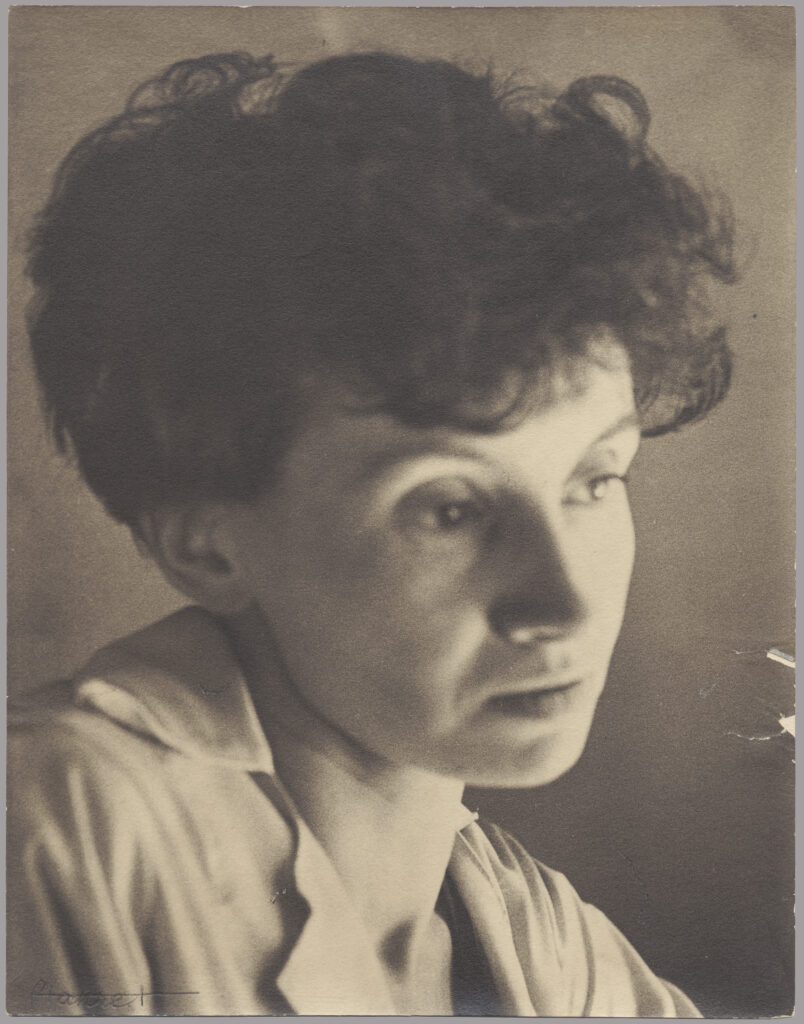

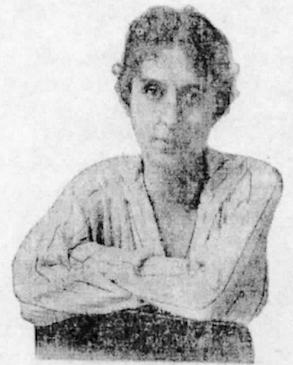

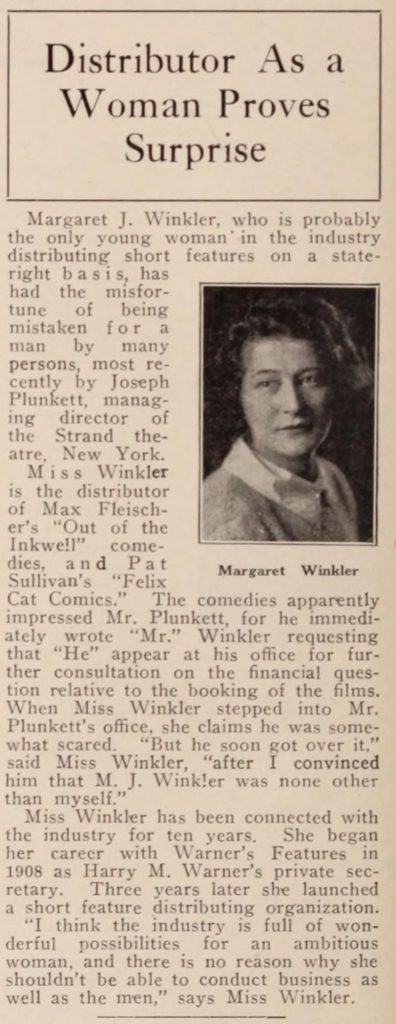

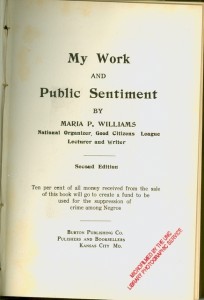

Diana Karenne was one of the most interesting personalities in the Italian and European film scenes of the early 1900s. Star, actress, intellectual, artist, director, screenwriter, and producer, she is representative of an effectual coexistence between two different ways of considering a woman’s role in both the film industry and in a society that was undergoing deep changes as to gender boundaries (Guerra 2008, 39; Pravadelli 2014, 5; Vicarelli 2007, 13). Through her artistic career, she supported demands concerning female identity, widely felt between 1800 and 1900 (Bianchi 1969, 190): in this very period, Europe was facing a process of modernization and large transformations at every social level. Karenne never took sides towards women’s emancipation movements, yet she opposed conservative morals and social conventions of that time through her personal, aesthetic, and professional choices (Gaines 2008, 20), and helped to update the idea of cinema thanks to her bold artistic proposals and acting style (Bianchi 192).

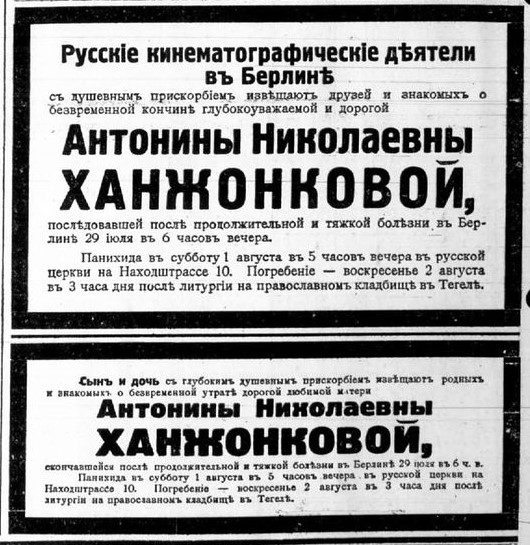

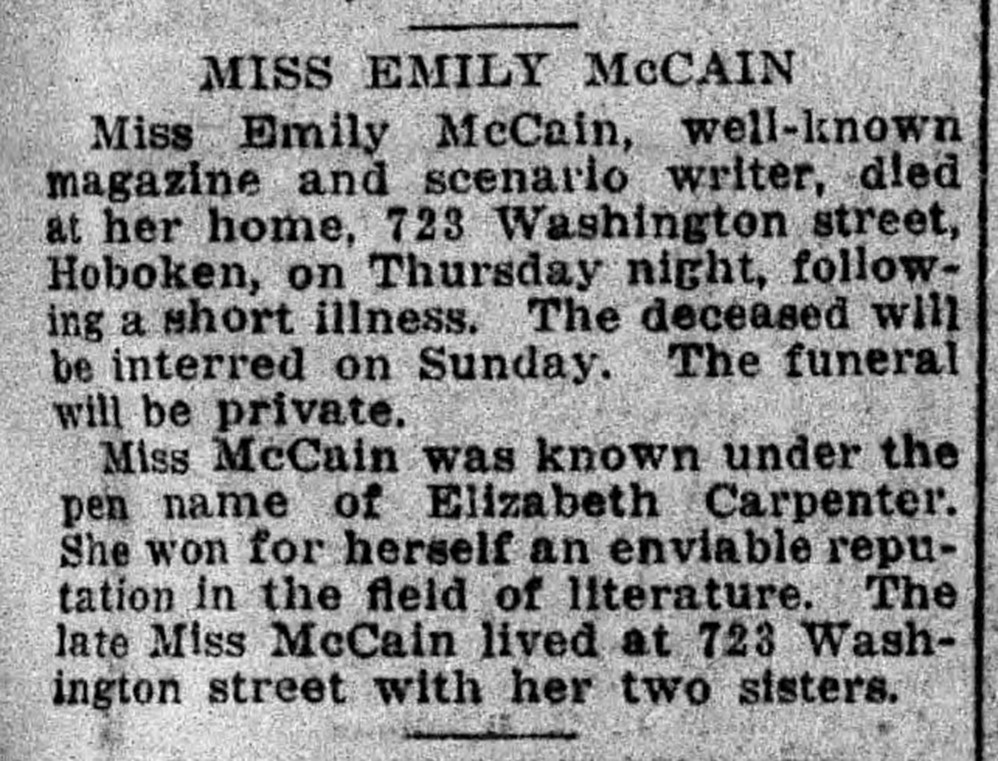

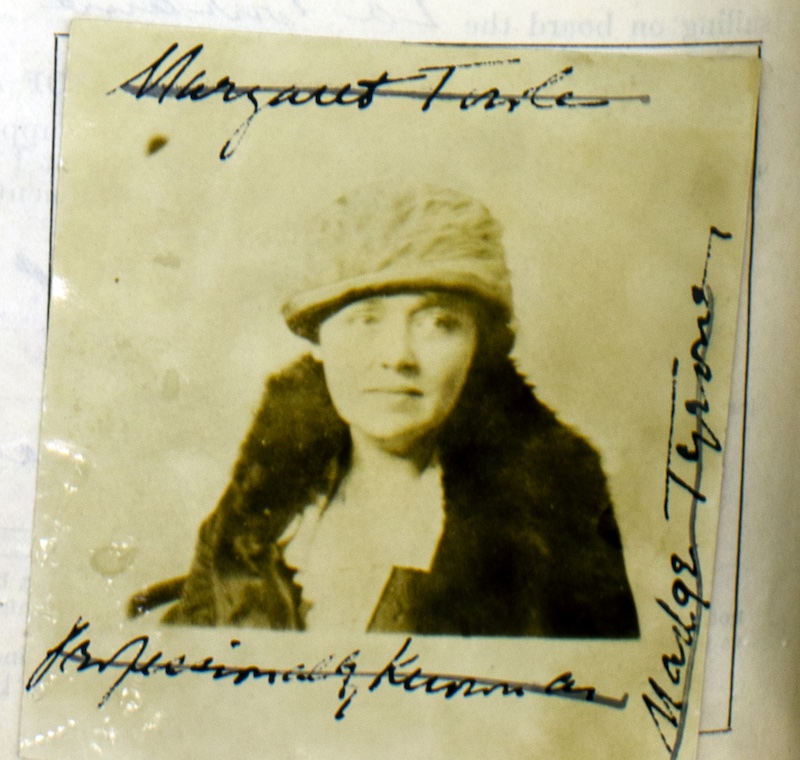

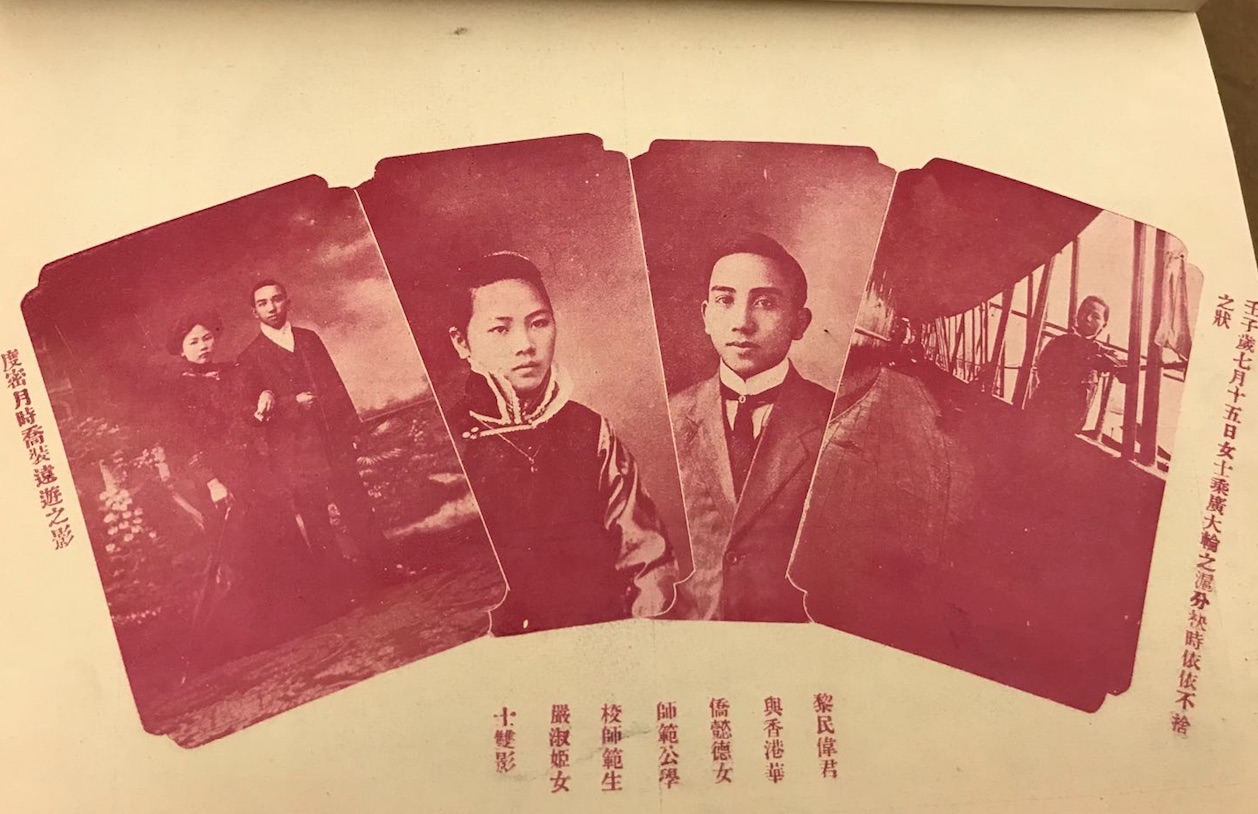

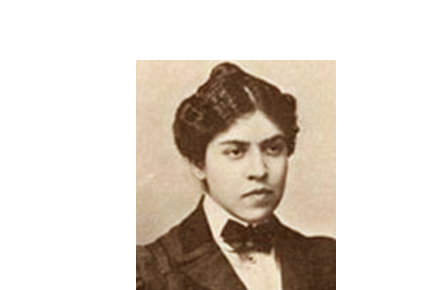

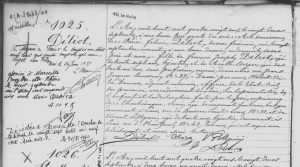

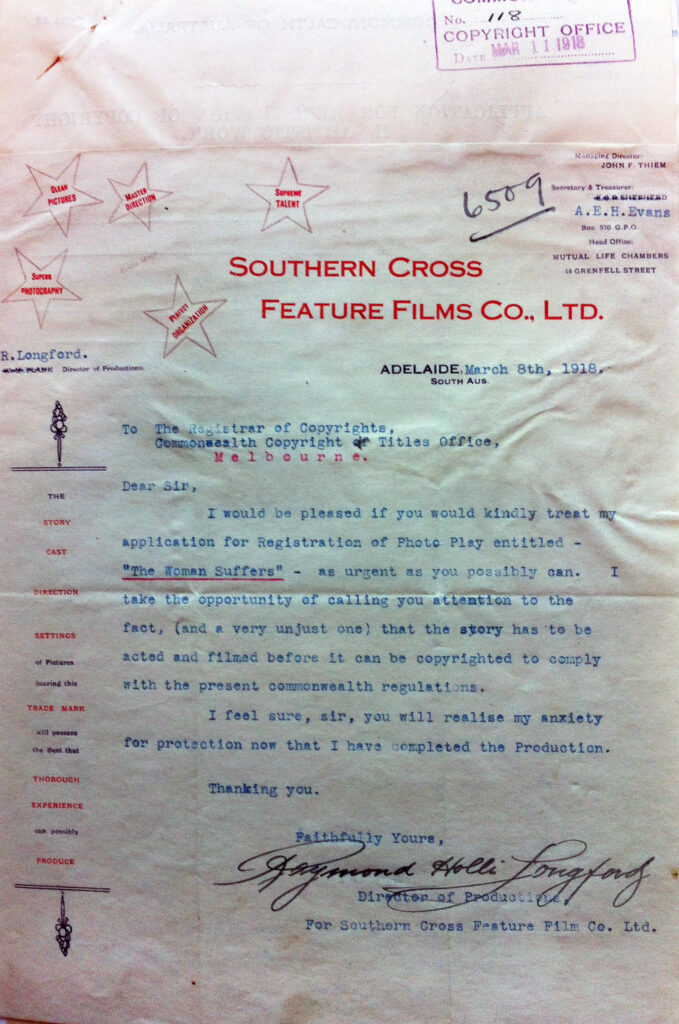

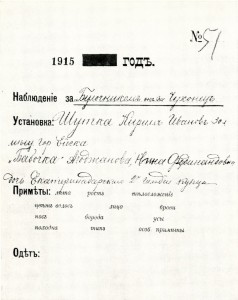

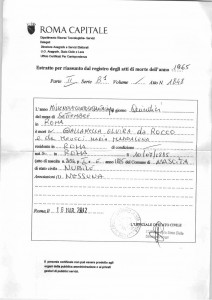

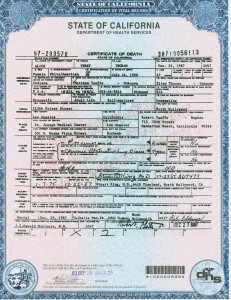

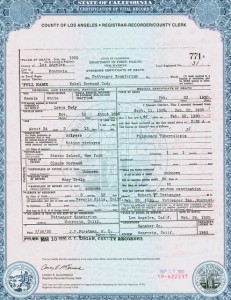

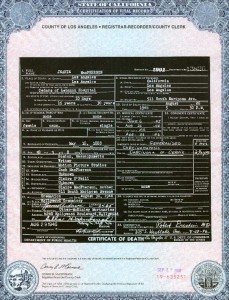

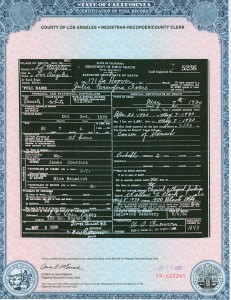

She was born Dina Rabinovič in Kiev on June 22, 1891. Her birth certificate was only recently discovered (Mazzucco 2024). Prior to that, we could not confirm her birth name or her date of birth; we only had the numerous names and patronymics that were attributed to her over the years, including Leucadia, Dina, Diana, Bianca, Rina, Anna, Nadejda, Konstantia, Konstantin, Belogorsky, Rabinovich, Belogorskaya, Karenne, Karenina, Otzoupe, Belocorsca, and Karren.

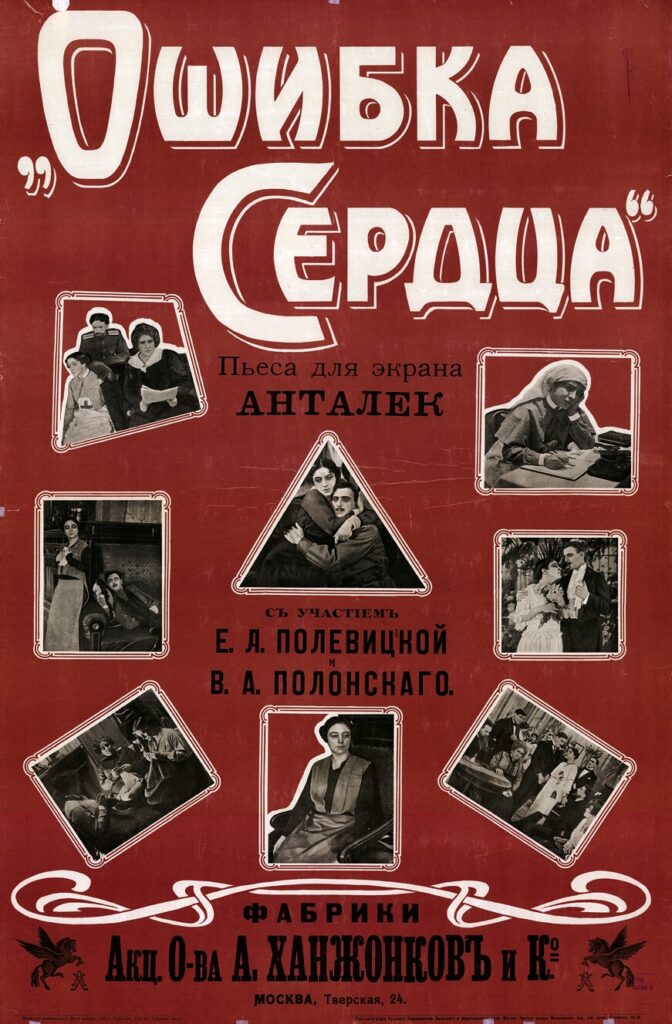

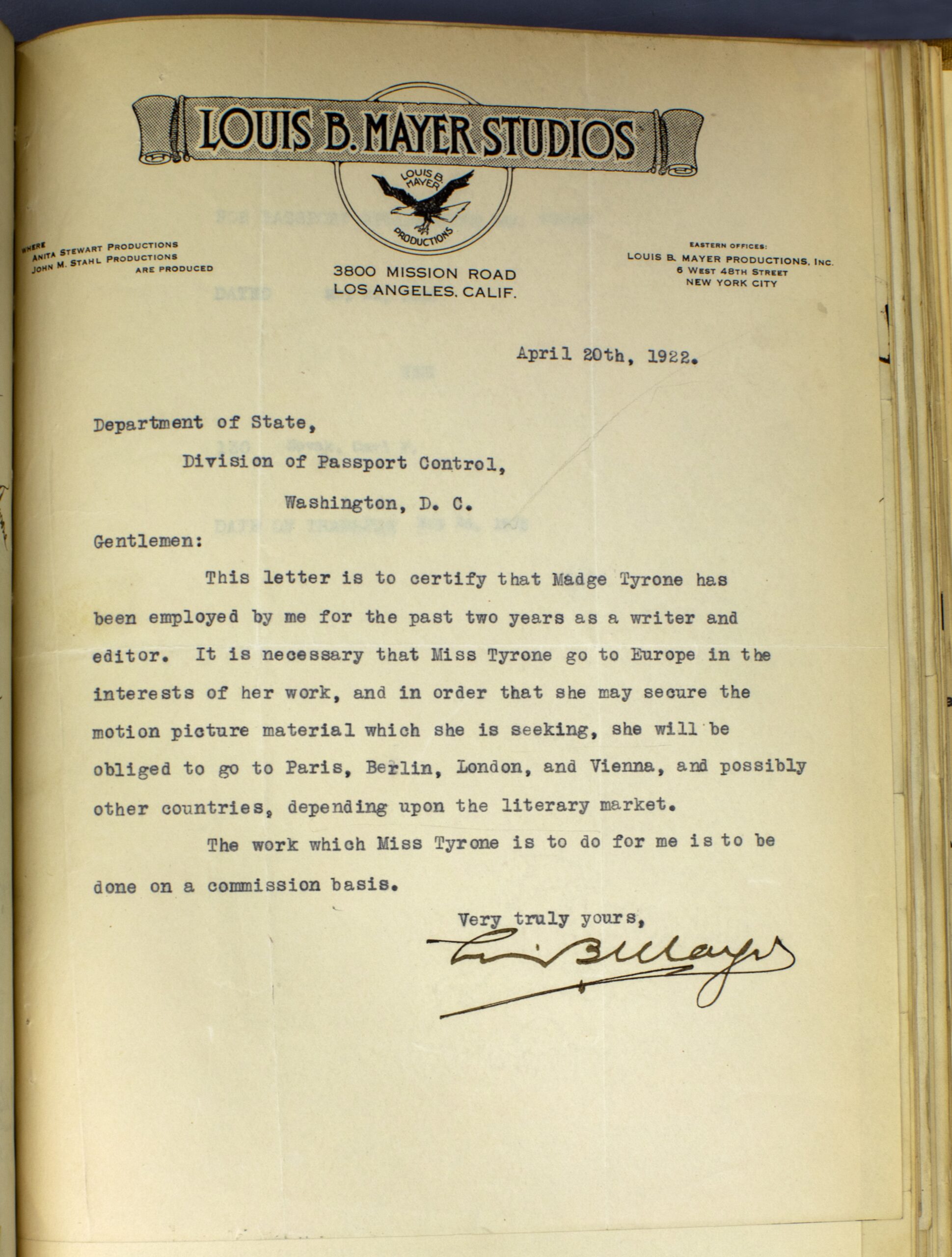

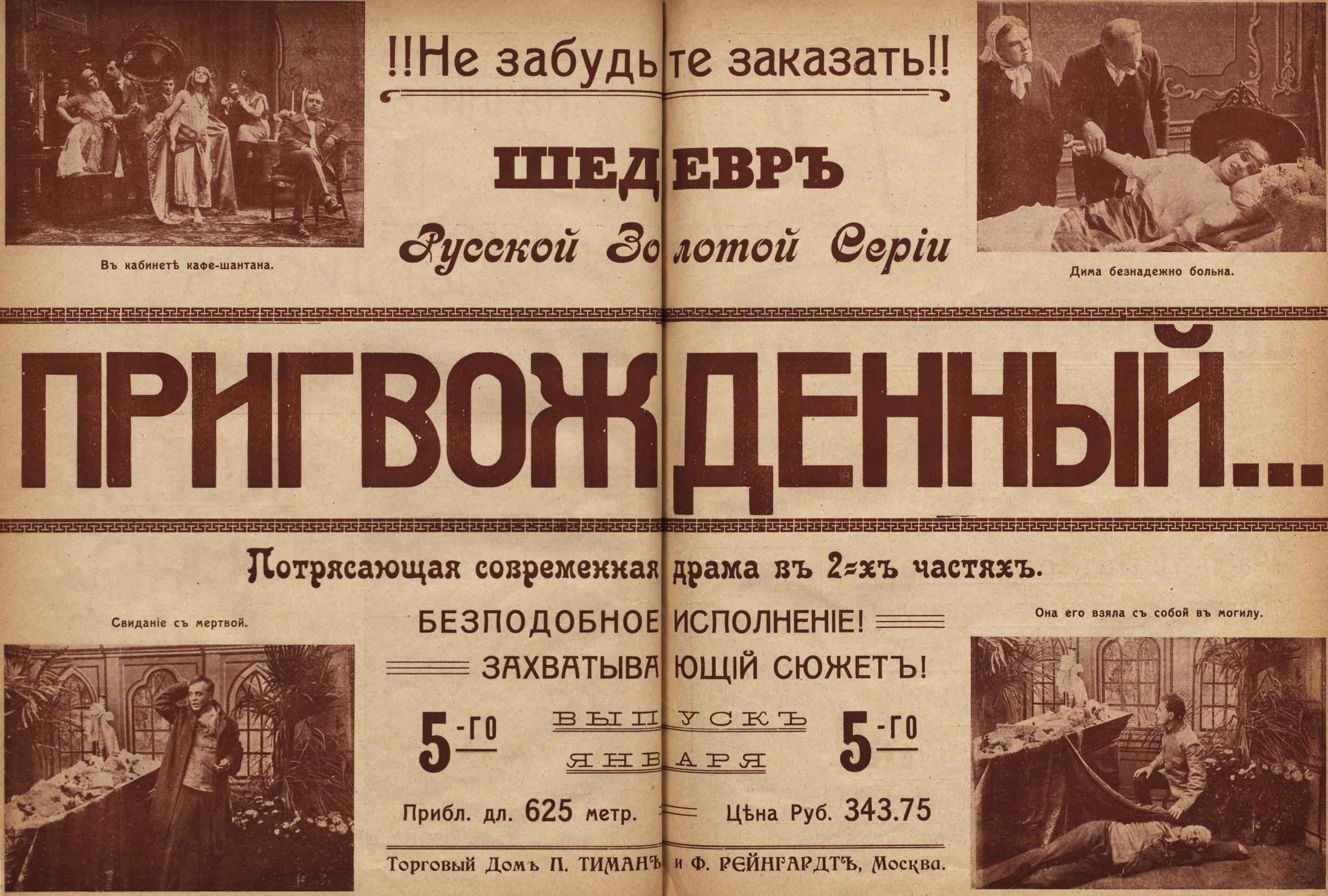

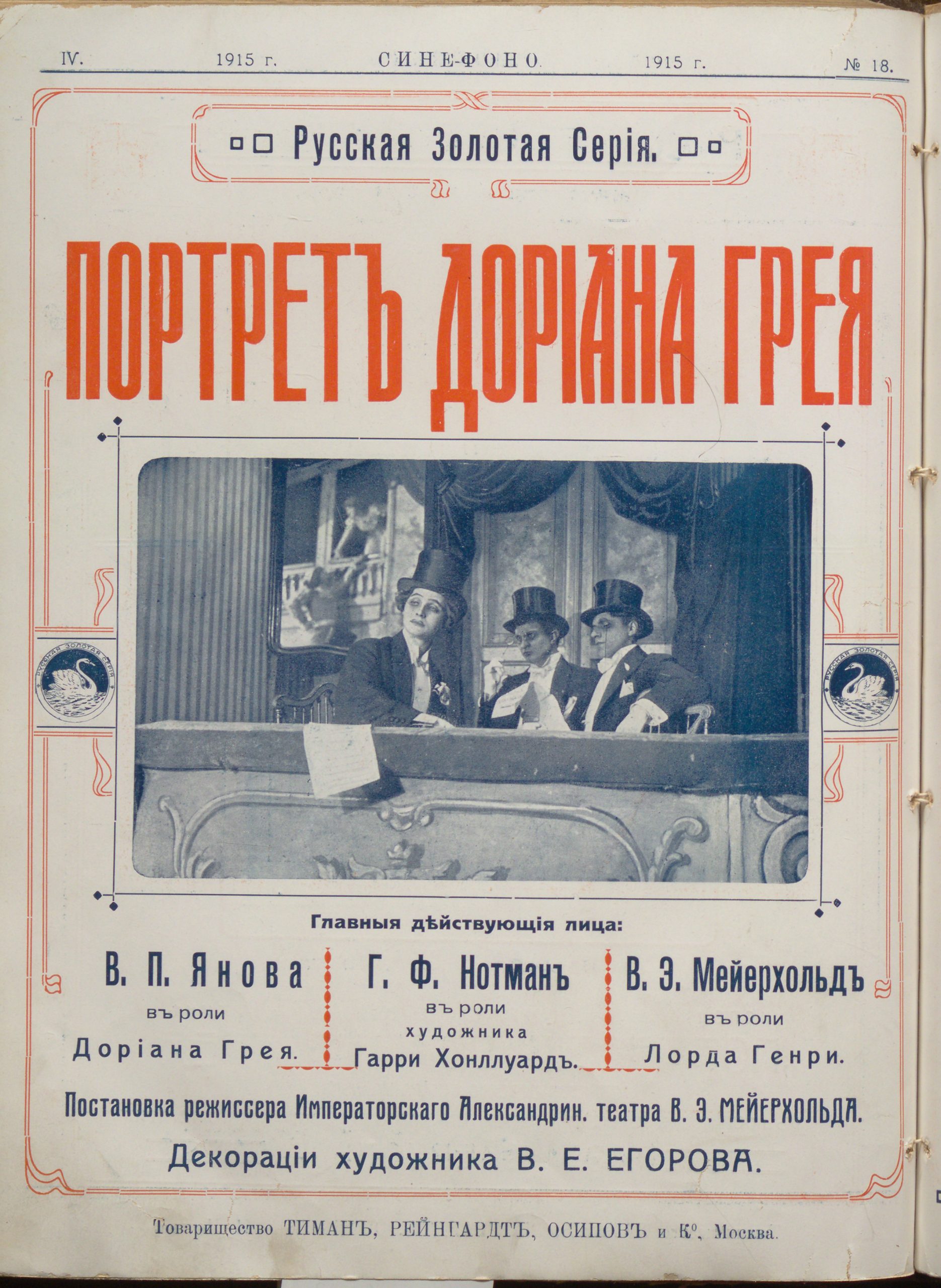

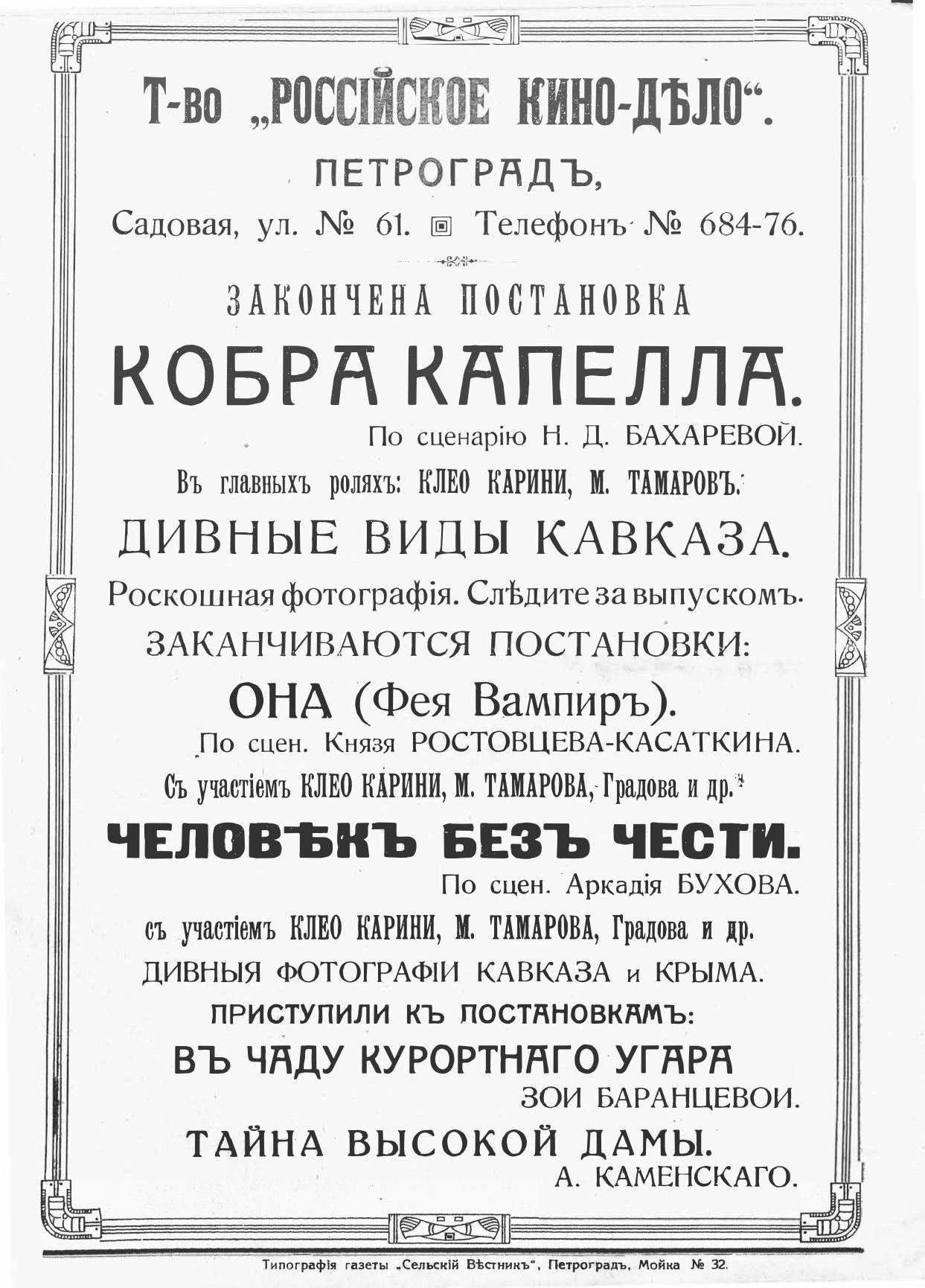

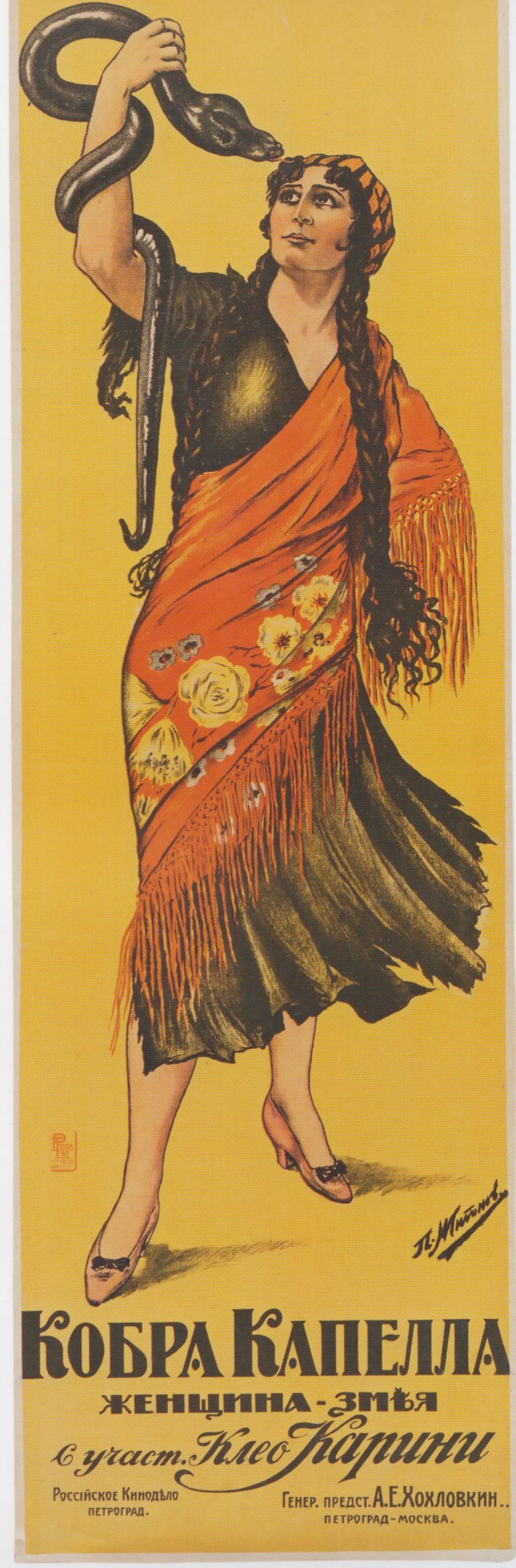

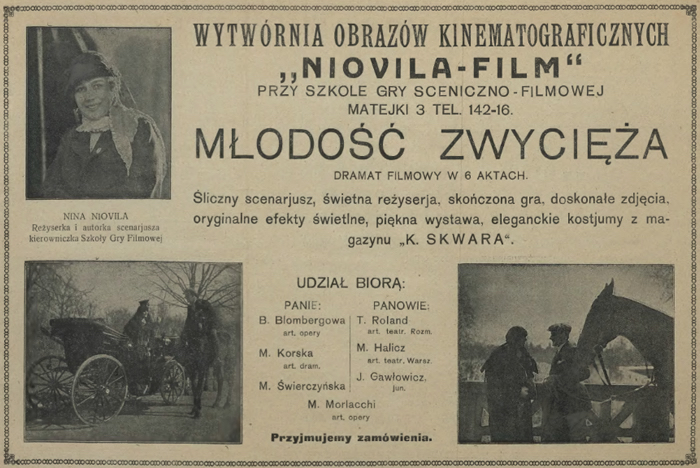

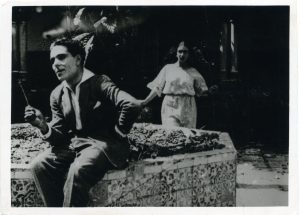

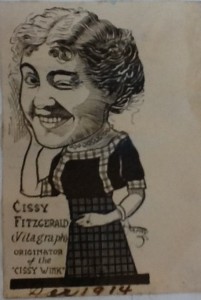

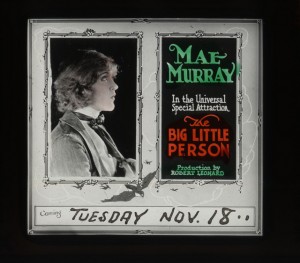

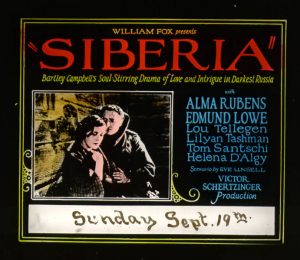

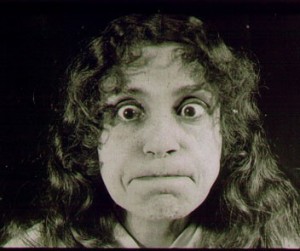

Until recently, it was also believed that her film career begin in 1914 in Italy, but we now know that in 1913, in imperial Russia, she starred under the name Dina Karen in Tragedyia dvuch’ sester/The Tragedy of the Two Sisters. In the film, she plays a dual role as the two female relatives of the title, communicating their different temperaments via carefully differentiated mannerisms. The film was produced by one of the most important Russian film companies of the pre-revolutionary period, A. Drankov and A. Taldykin. An advertisement for the film in the January 1914 issue of the Russian magazine Cine-Phono credits her as both actress and the screenwriter of this drama (Cine-Phono). A fragment of this film survives at Gosfilmofond in Moscow (Shvediuk 2024).

At the end of 1914, she moved to Italy, first to Rome and then to Turin. The Italian police, suspecting her of political espionage, began to spy on her following her move from Russia. The dossier of the Italian Ministry of the Interior kept in the Central State Archive in Rome contains documents showing that the actress was ultimately under surveillance for more than twenty years, until 1938, without any conclusive evidence being found against her.

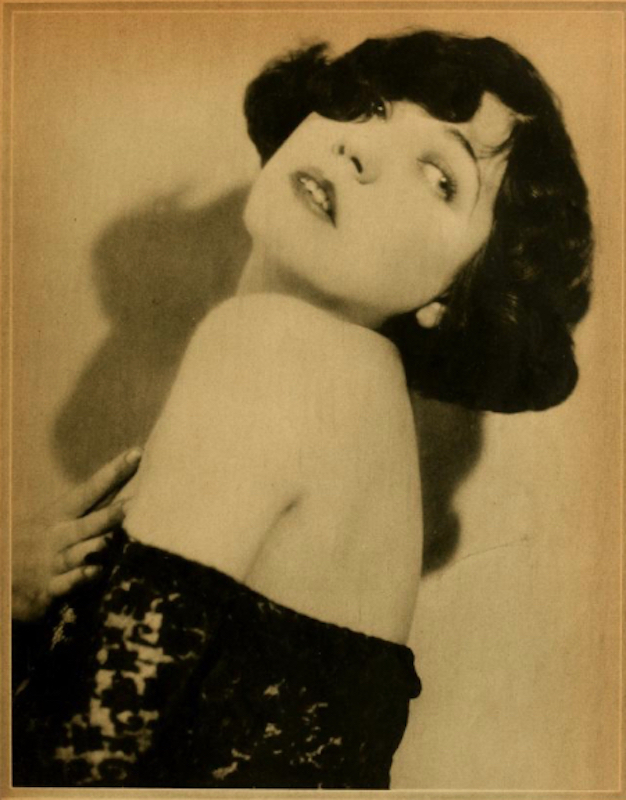

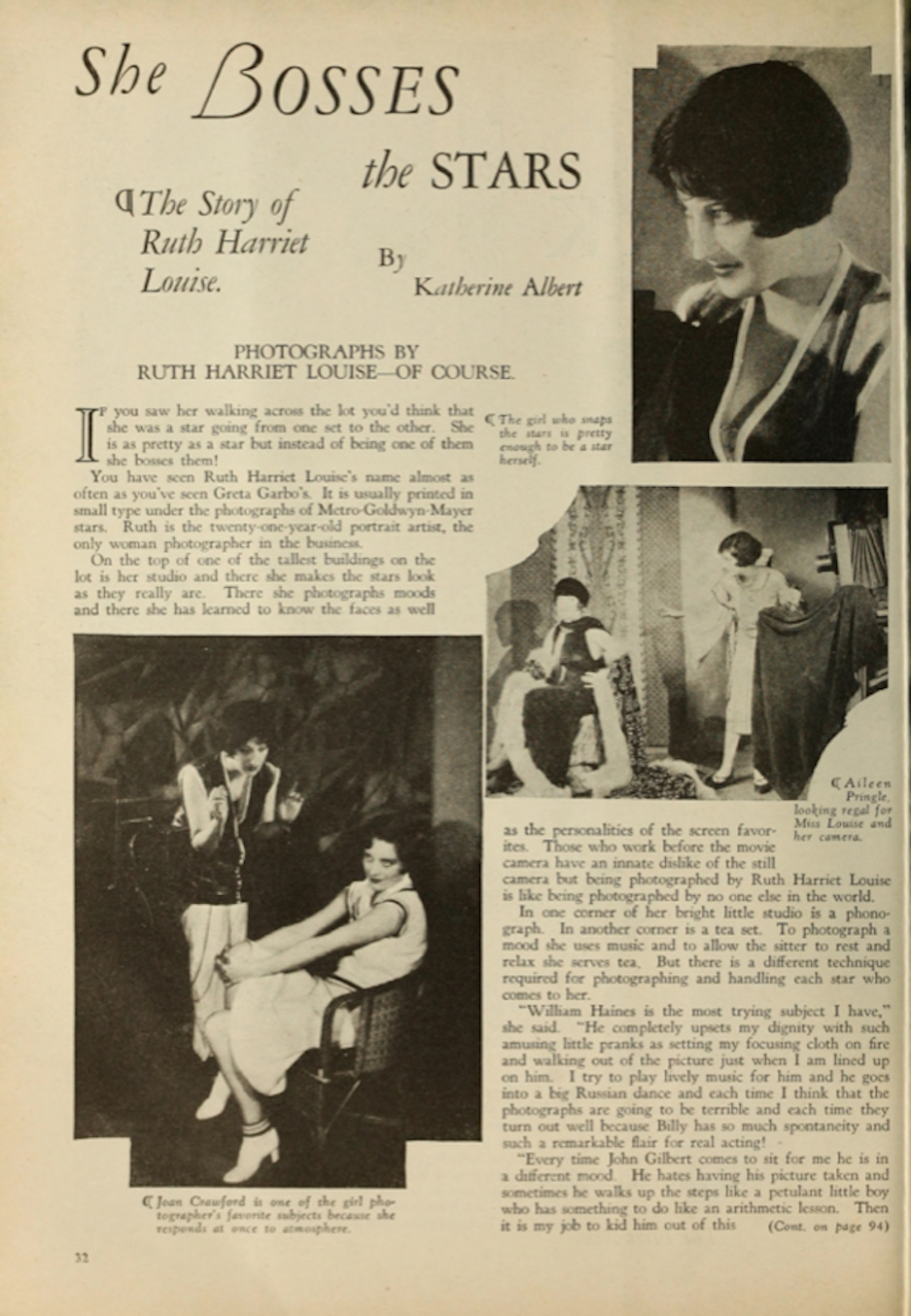

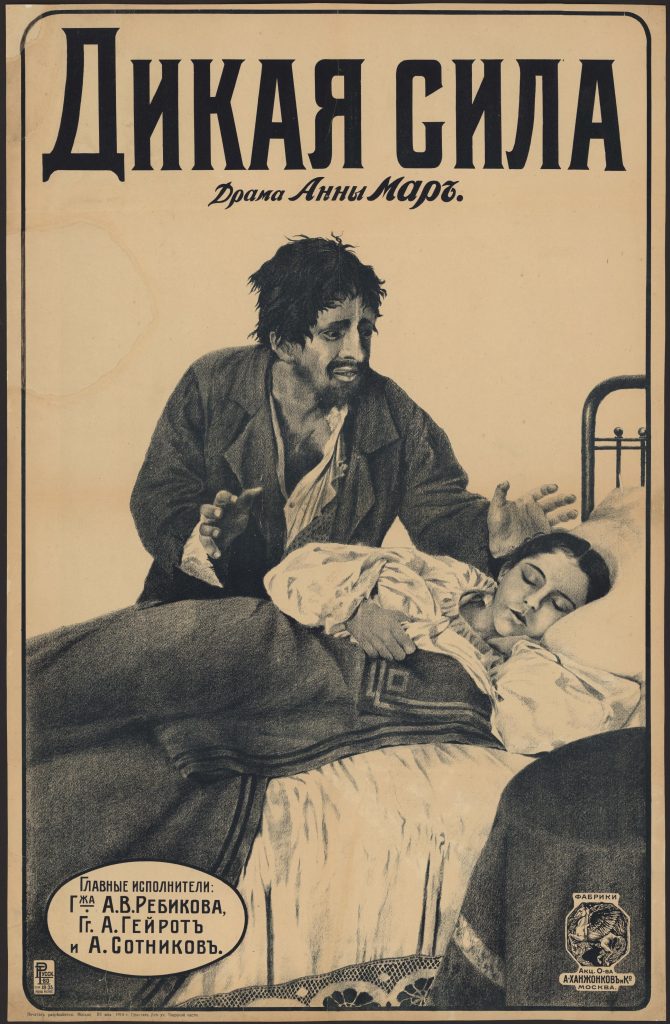

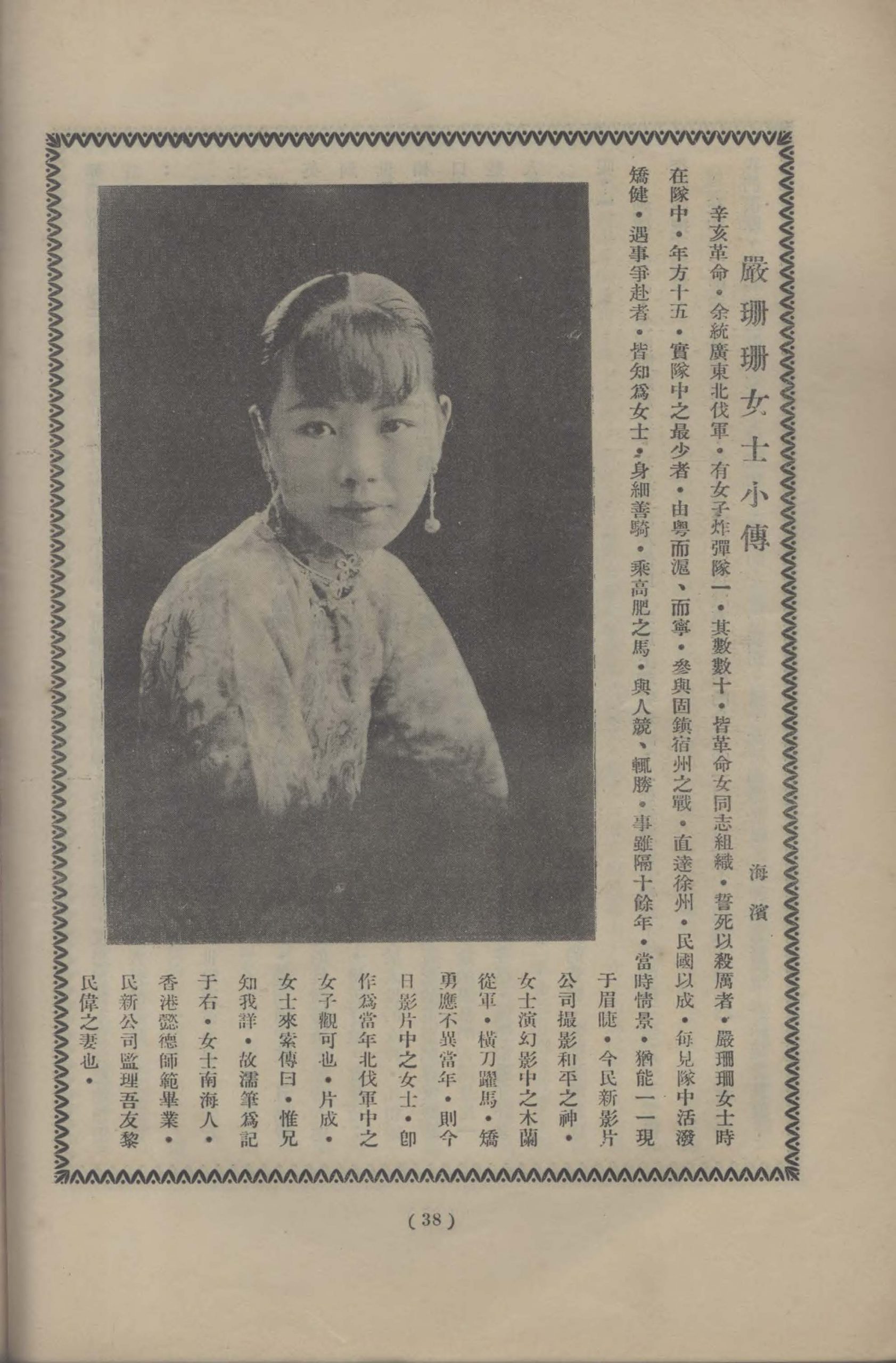

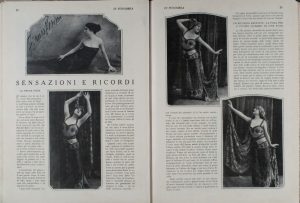

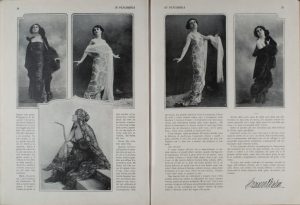

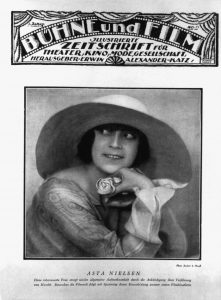

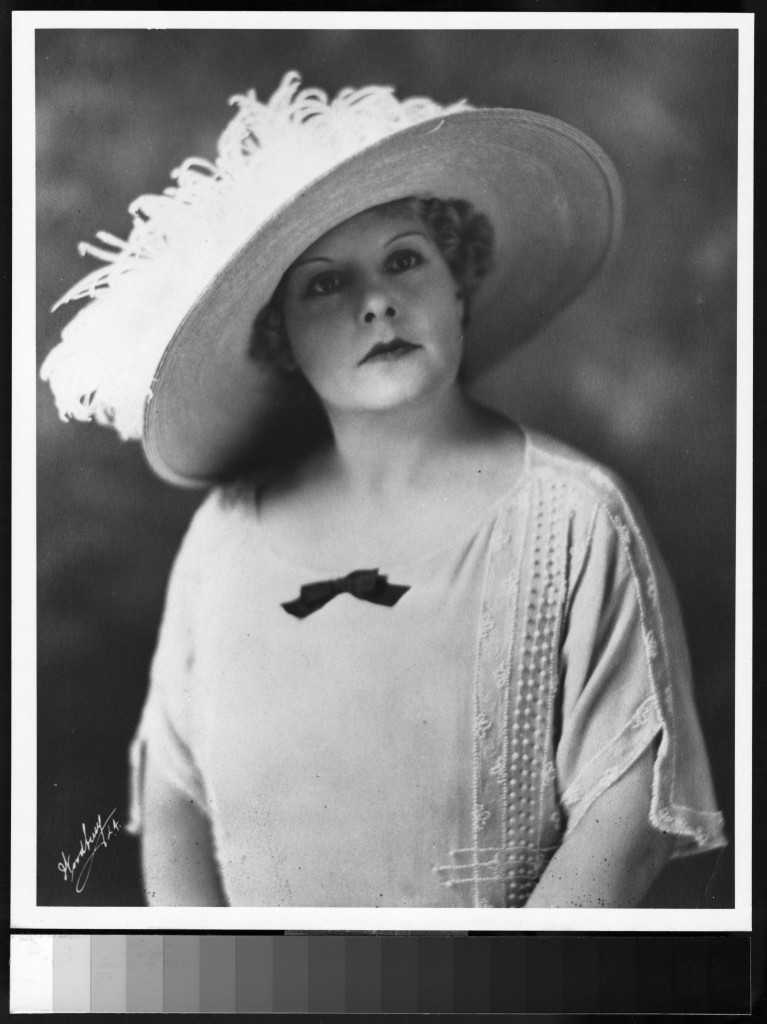

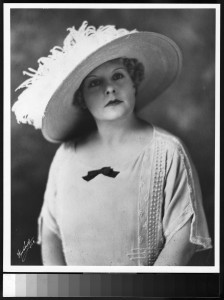

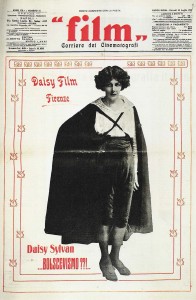

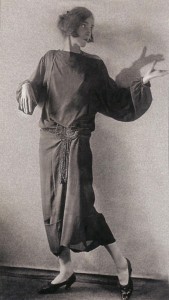

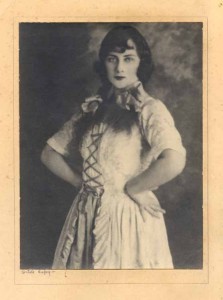

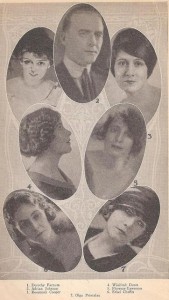

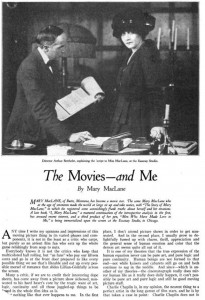

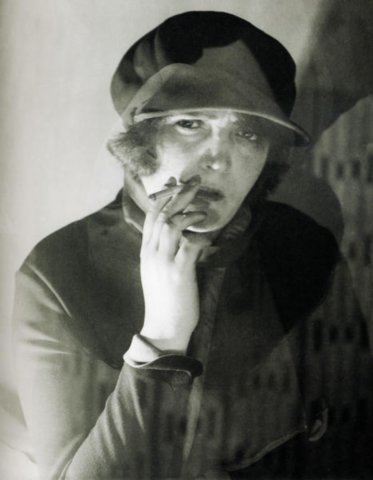

Between 1914 and 1915, Karenne entered into a professional and intimate relationship with producer Ernesto Maria Pasquali, who signed her up at Pasquali Film and cast her as the leading actress in Passione tsigana (1916). This film was a hugely popular success and launched the actress—who now went by the name Diana Karenne—into the Italian film scene thanks to her beauty and vivid acting. The characteristics of her performance were unusual—besides her peculiar, natural style, she was the first Italian star of that time who dared to look straight into the camera. Karenne was able to immediately construct a unique star persona. On one hand, she showed the usual features of a film star at that time: beauty, grace, elegance, competition (real or supposed) with other leading actresses, gossip on her star fancies, wide international celebrity, and popular fandom. On the other hand, however, she offered the image of a modern and unconventional woman who kept away from the stereotype of a star as only a good-looking object and proposed a new way of thinking about the actress as an intellectual artist. Press outlets, such as La rivista cinematografica, used to call her “the most intelligent of all” (1923, 53; Alacci 1919, 50; Bianchi 190).

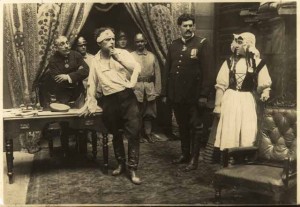

In 1916, Karenne started climbing to the top of her splendid career as a star. The actress was in almost unanimous favor with the press, in spite of her frequent clashes with censorship and unfriendly attitudes on the side of some film critics. In her second film with Pasquali, La contessa Arsenia (1916), she confirmed her talent and success. In her third picture, Quand l’amour refleurit (1916), she worked behind the camera as well, writing the story treatment (Jandelli 2006, 212). In Oltre la vita, oltre la morte/Anime solitarie (1916), she had the chance to work closely with Alberto Capozzi, considered to be one of the most outstanding Italian actors of that time. Around mid-1916, Karenne temporarily parted with Pasquali Film and moved to Jupiter Film, in Turin, where she acted in Il marchio (1916). Soon after she became a director for the first time, shooting Lea (1916) for Sabaudo Film (Jandelli 2006, 212). Guglielmo Zorzi helped her adapt the homonymous novel by the radical writer Felice Cavallotti for the screen. After Lea, Karenne went back to Pasquali Film to be directed in Sofia di Kravonia (1916). This was probably her last collaboration with Pasquali, who died in 1919 from a serious form of hyperthyroidism. It seems, however, that their love affair went on until his death (Martinelli 2001, 142). At some point in 1916, she moved to Aquila Film, where, though not mentioned in the credits, she attracted the audience’s attention for her showy make-up in Karval lo spione (1916) (Jandelli 2006, 211).

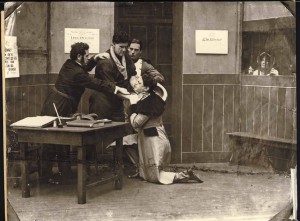

Towards the end of 1916, Karenne collaborated with Megale Film on Catena (1916), acting in the film and supervising the mise-en-scène. In 1917, when she was already one of the most sought-after and successful stars of Italian cinema, Karenne went under contract with Ambrosio Film in Turin, where she took part in the serial Il fiacre n° 13/Cab Number 13 (1917). In the same year, Karenne went back to directing with Il romanzo di Maud (1917), adapted from Les demi-vierges, a novel by Marcel Prévost. Working on that film turned out to be very hard because of a number of violent clashes with censorship, and marked the end of the contract between Ambrosio Film and Karenne (Jandelli 2006, 212).

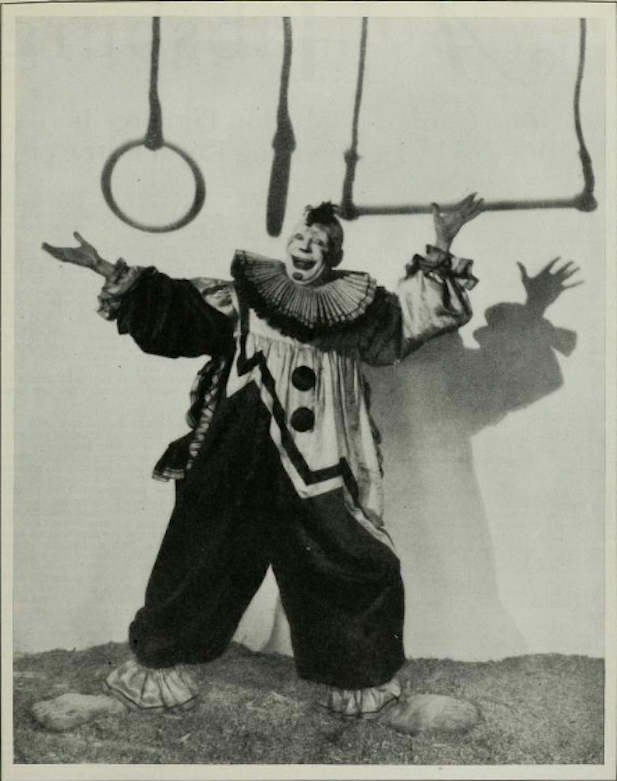

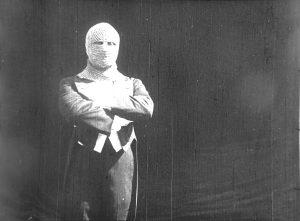

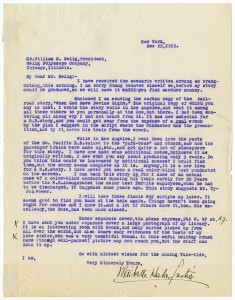

The most important event in 1917, however, was the establishment of the film company David-Karenne by Manfredo Lombardi and Bernardo Cecconi (Jandelli 2006, 213). Its artistic plan included top-level productions and Karenne was put in charge of the whole film manufacturing process. David-Karenne Film started its activity with Pierrot (1917), for which Karenne supervised the story, direction, and staging, and played the demanding leading role en travesti. Unfortunately, very soon the society showed serious economic problems. For instance, Lombardi had commissioned the writer and journalist Matilde Serao to write two original stories for two films starring Karenne. The fee had to be 16,000 liras, but when the first film, Il doppio volto, was handed in, no payment followed (Annunziata 2008, 250). Serao withdrew from the contract and threatened to sue Lombardi, but, according to a February 10, 1917, article in La cine-gazetta, after a long series of failed attempts at reaching an agreement, she renounced her fee and abandoned the lawsuit (4).

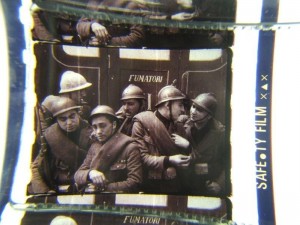

In May 1917, Karenne’s career arrived at a new turning point: the actress decided to take over David-Karenne Film, which was still undergoing serious financial problems. She renamed it Karenne Film and started producing pictures on her own. The first two films produced, directed, and starring Karenne were Justice de femme (1917) and La damina di porcellana (1917). In 1918, in addition to her activity at Karenne Film, she continued to work with other production companies, taking roles in the fourth episode of Trittico italico (1918), a propaganda film produced by Cines and the Ministry of the Navy, and in the series “Karenne Films” that Tiber Film, in Rome, had launched especially for her. This series included La peccatrice casta (1918), La fiamma e le ceneri (1919), and La signora delle rose (1919), where Karenne joined Gaetano Campanile Mancini in writing the script. Around March or April 1918, she started working with Medusa Film on the production of the historical epic Maria di Magdala (1919), which was renamed Redenzione. This film was released in Italian theaters at the beginning of the following year, met with outstanding success, and cemented Karenne’s performance in the history of silent cinema. In the meantime, the actress applied herself to Sleima (1919) as director, producer, and star, and then acted in Zoya/La signorina Zoya (1920), her last picture with Tiber Film.

In 1919, Karenne left Tiber Film, probably because of some internal disagreement, as highlighted in the satirical magazine Contropelo, which often commented on the arguments the actress was said to have with Mecheri, the owner of the society (1918, 8). She entered into a contract with Umberto Fracchia’s Tespi Film, which launched a “Series Diana Karenne” just for her. The series included: Ave Maria (1920), which she also directed, La spada di Damocle (1920), Catene infrante (1920), and Oghzala (1920), all co-produced by Karenne Film. In October, she started shooting Indiana (1920), adapted from a novel by George Sand, scripted and directed by Fracchia. In 1920, Karenne worked on her last known title as director and producer for Karenne Film: La veggente (1920). After one more picture with Tespi Film, La studentessa di Gand (1920), Karenne moved to Nova Film, where she took part in the well-received Miss Dorothy (1920) and Smarrita! (1921). At that time, Karenne had her appendix removed, which forced her to rest for a few months. She then recovered completely and resumed work.

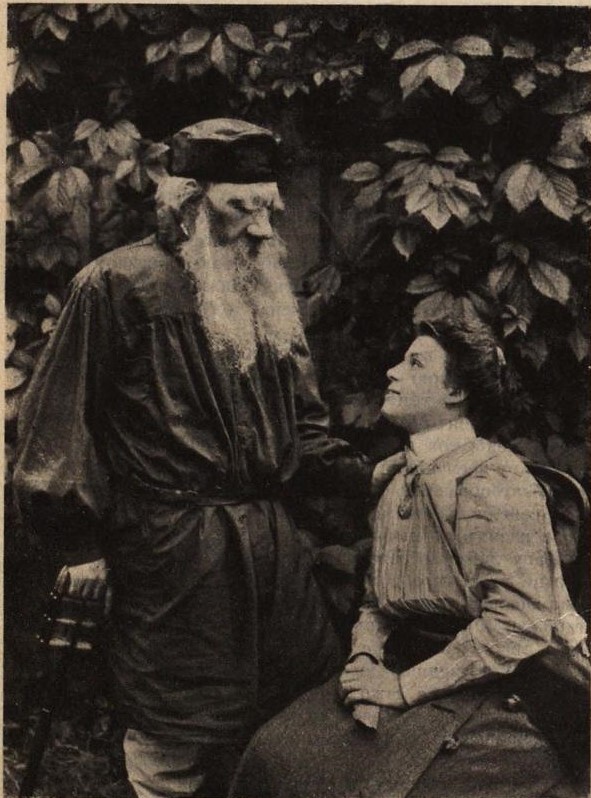

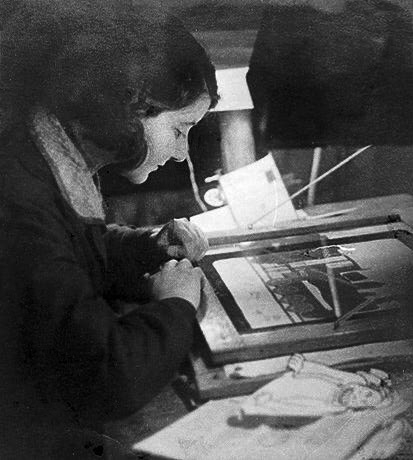

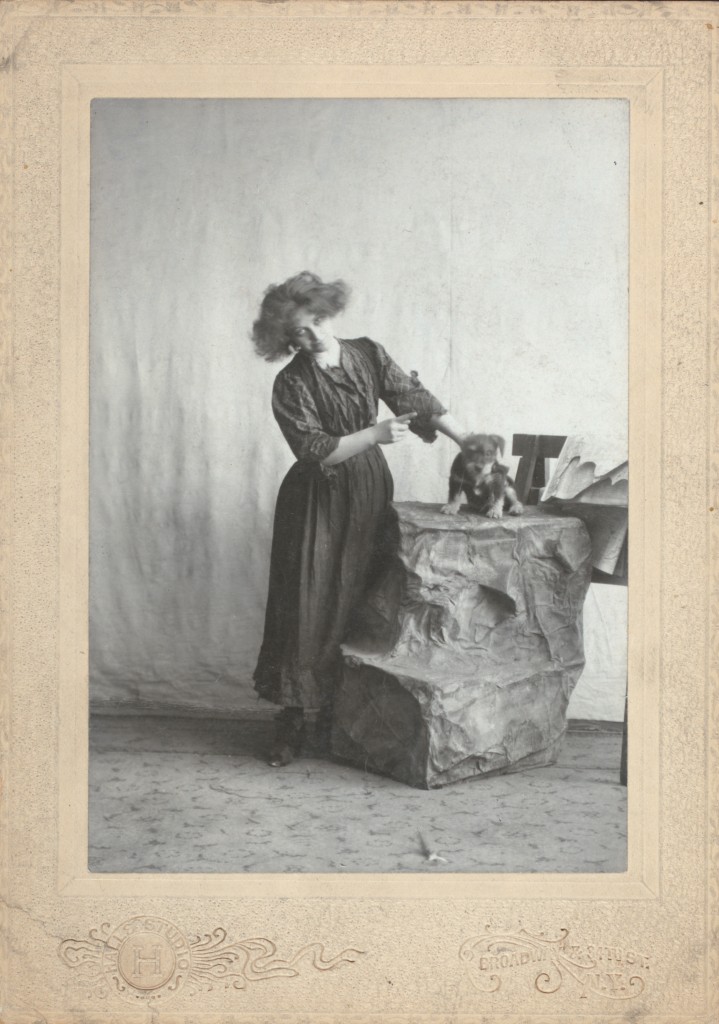

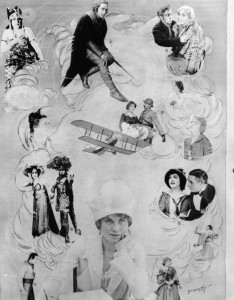

Karenne had an outstanding artistic knowledge and education. Creative as she was, among her talents we can mention painting and drawing—she created Disegni fantastici (a series of paintings that represent faces expressing different emotions) in a vaguely expressionistic style, maybe while she was training for her performance in Pierrot. Additionally, Karenne was musically gifted and could play the piano, as shown in a scene from Miss Dorothy, where she visibly plays the instrument without the use of editing. She also befriended a number of Italian intellectuals, among whom some leading figures of the futurist circle can be found, in particular writer Fracchia, who was also the general manager of Tespi Film, and artist Arnaldo Ginna.

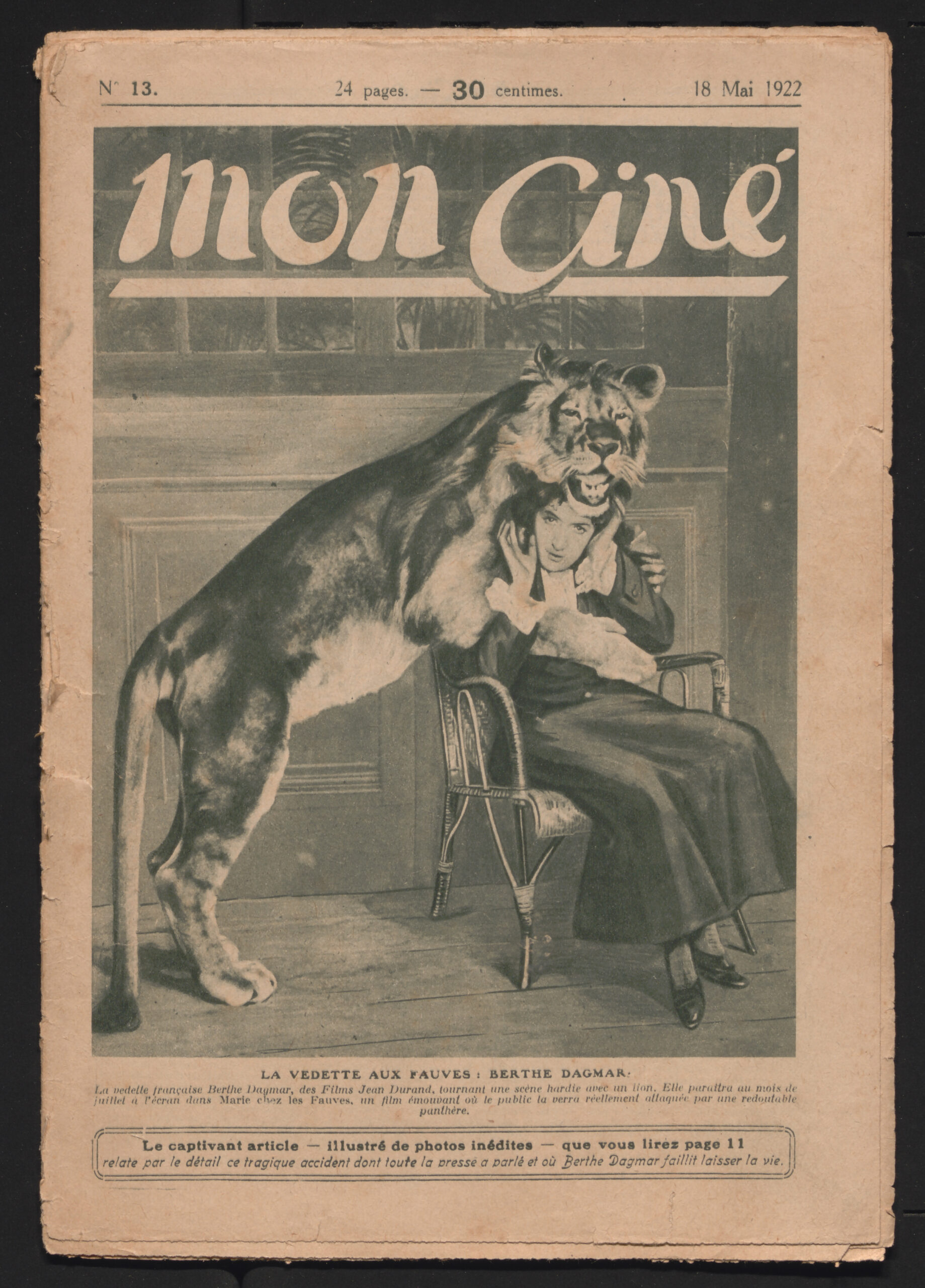

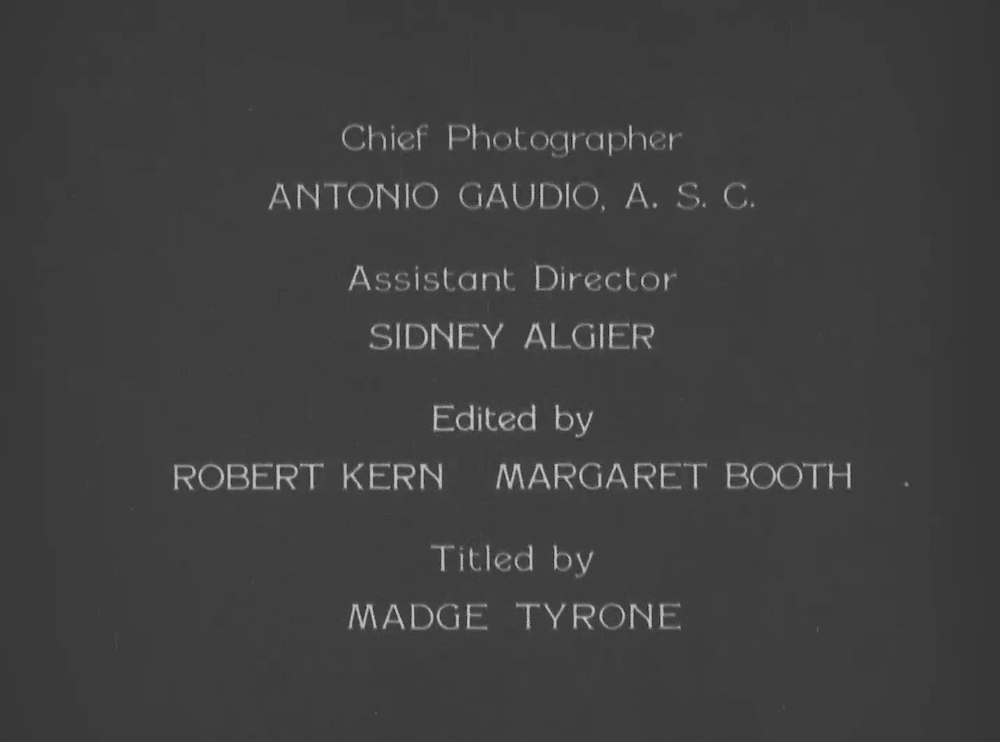

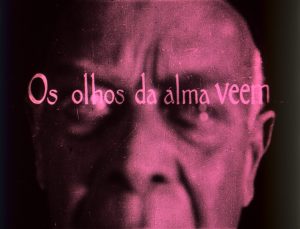

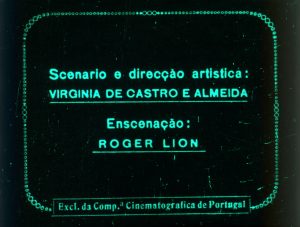

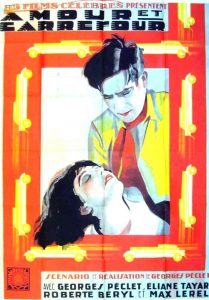

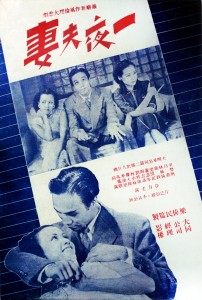

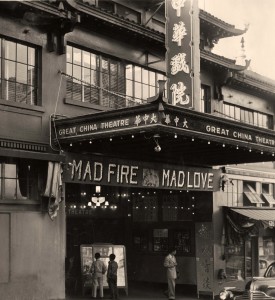

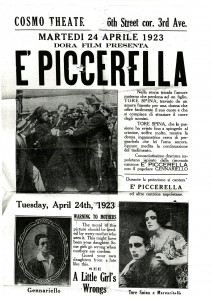

Throughout her time working in Italy, the film industry there was undergoing a serious crisis that had started in 1915, when the country entered World War I, and that affected “diva films,” as popular as they were (Alovisio 2014, 19-24; Bianchi 79-82). This eventually led Karenne to make the decision to leave Italy and find a job abroad, with no language obstacles due to the absence of sound in films. At the beginning of 1921, she was in Berlin shooting Das Spiel mit dem Feuer/Playing with Fire (1921) with Robert Wiene. She went back to Italy a month-and-a-half later to take part in the challenging historical reconstruction Dante nella vita e nei tempi suoi (1922). The film was written by Valentino Soldani and directed by Domenico Gaido for V.I.S. (Visioni Italiane Storiche) on the occasion of Dante’s centennial and it was a stunning success. From then on, however, Karenne worked almost solely abroad, going back to Italy just for short periods of rest. In those years, her producing and managing experience at Karenne Film also came to an end. While it is uncertain exactly when she closed down her company, a major reason was surely her move abroad, along with a hostile attitude towards female professionals that was still prevalent at the time. In France, Karenne worked with the company Visions of Art and with Ermolieff Cinema, shooting L’ombre du péché (1922) for the former and Le sens de la mort/The Meaning of Death (1922) for the latter. In Germany, I.F.A. and Meinert Film engaged her for another historical drama, Marie Antoinette (1922). With Transozean Film, she had a role in Arme Sünderin (1923); for Caesar Film, she made Frühlingsfluten (1924); and for Richard-Oswald Produktion, she acted in Die Frau von vierzig Jahren/A Woman of Forty (1925). Information about these years in Germany is very scarce and less and less reliable. Her presence in France, however, seems to be confirmed, as the actress took part in the film adaptation of Giacomo Casanova’s Histoire de ma vie, Casanova (1927), for Société des Cinéromans.

In 1928, Karenne traveled back to Italy for the last time to appear in La vena d’oro (1928), based on a play by Guglielmo Zorzi, who also directed the film. In 1928 and 1929, she went back and forth between Germany and France. In Germany, she shot Rasputins Liebesabenteuer/Rasputin, the Holy Sinner (1928), Liebeshölle/L’inferno dell’amore/Pawns of Passion (1928), and Die Weißen Rosen von Ravensberg/The White Roses of Ravensberg (1929); in France she played the double role of Marie Antoinette and her daughter Olivia in L’affaire du collier de la reine/La collana della regina (1929), one of the first French films to add a soundtrack. The last known performance of Karenne as a leading actress was in Fécondité/Fecundity (1929), which was produced by La Centrale Cinématographique and L’Écran d’Art, and was an adaptation of the novel by Émile Zola, for which she received high praise.

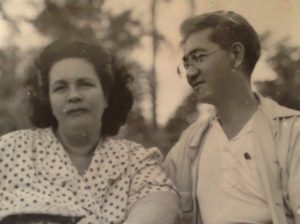

At the end of the 1920s, Karenne bowed out of cinema along with other stars and female figures engaged in the film industry at that time. The Depression and the rise of totalitarian regimes put an end to women’s emancipation efforts (Vicarelli 13). The film business took on more strict features and industrial rules, wiping out all experimentation and small independent companies. Finally, sound films, ultimately, ended the age of silent film stars (Bianchi 192; Martinelli 143). Her last film, and only sound role, was Manon Lescaut, made in 1940. Her presence is not easy to identify as it consists of a quick appearance, requested by her friend, director Carmine Gallone, and inserted in a film dominated by the Italian diva of the moment, Alida Valli. By that time, the Karenne had retired to Aachen, Germany, where she lived with her second husband, Russian poet Nikolai Avdeevič Ocup, whom she had married in the late 1920s.

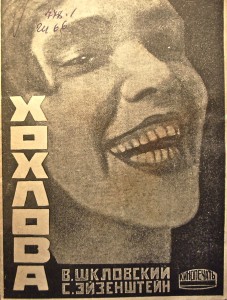

Around the time of her marriage, Karenne wrote a series of critical texts about cinema that were published in Parisian newspapers. This aspect of her intellectual career is an exciting new avenue for further research. From the 1930s onwards, Karenne devoted herself completely to married life and the work of her husband, who wrote two books about her, describing her with infinite admiration in Dnevnik v stikhakh (Diary in Verse, 1950) and in “Zhizn” i smert’ (Life and Death, 2 vols., 1961). Ocup’s memoirs, which Karenne published after extensive editorial work on his papers, are, as above, currently one of the most interesting sources related to her that remain to be explored in detail. While a previous version of this profile believed, following many other sources, that she had died during the Aachen bombings in 1940, extensive recent archival investigations conducted by Melania Mazzucco and Tamara Shvediuk show that this was not the case. She died on October 18, 1968, in Lausanne, Switzerland, of a heart attack (Mazzucco; Shvediuk).

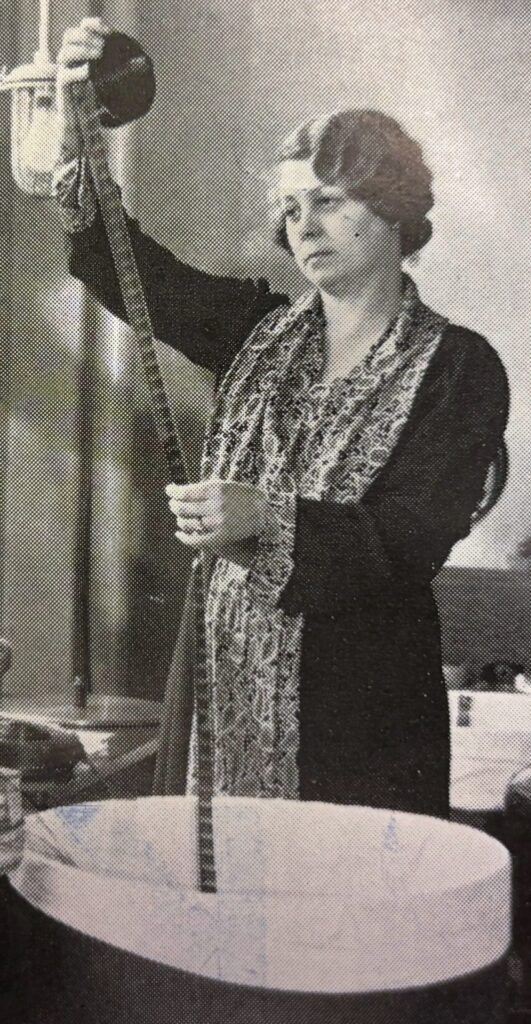

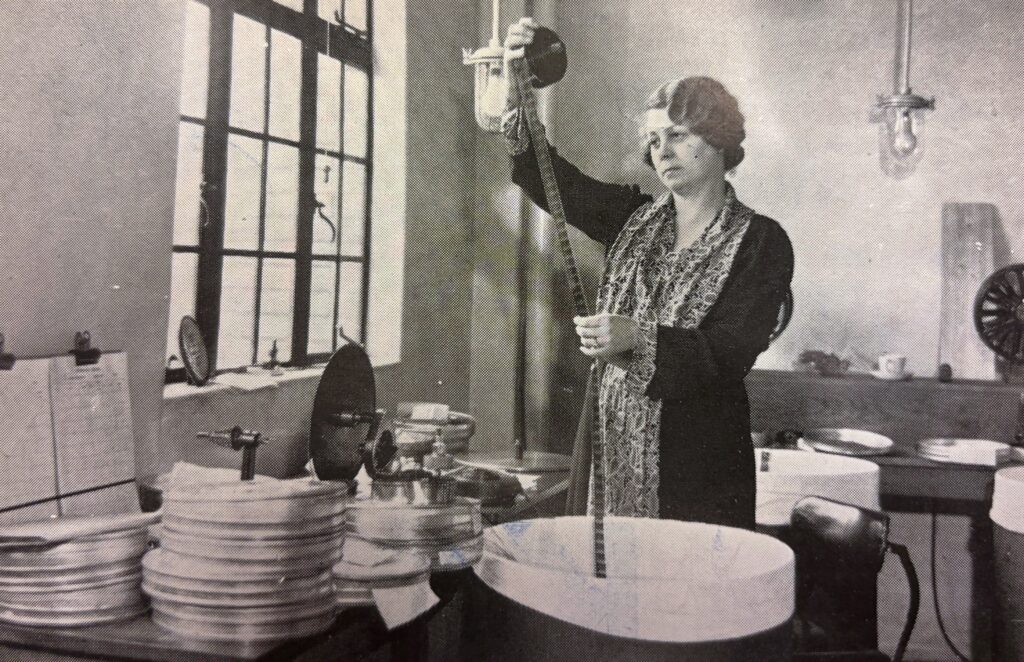

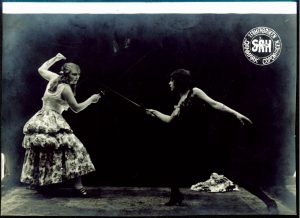

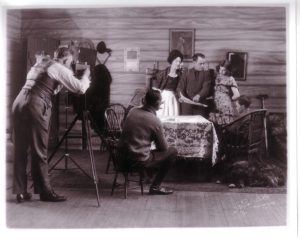

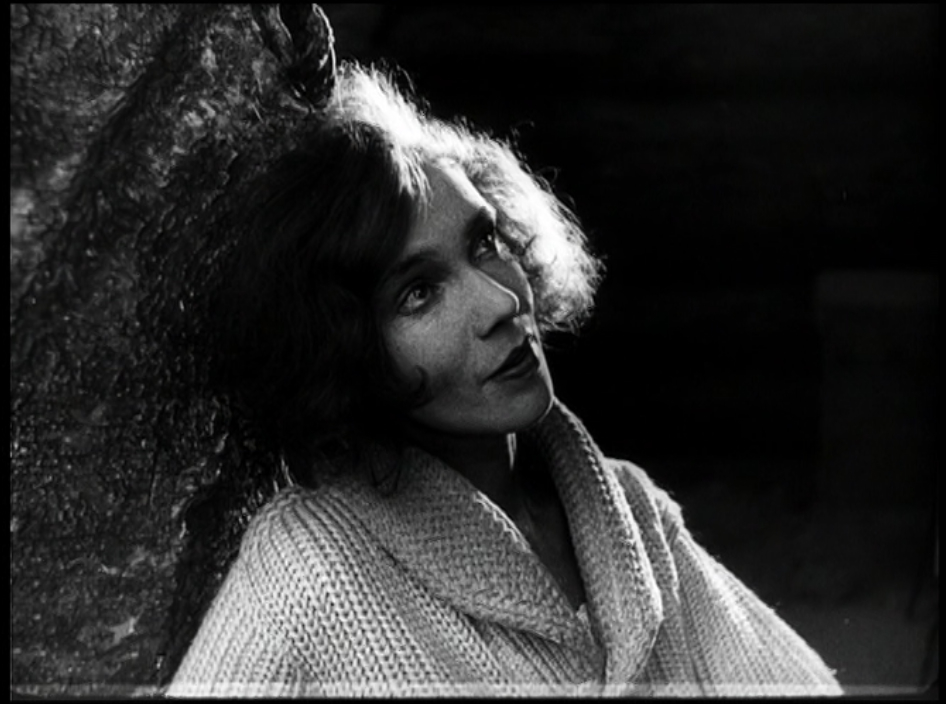

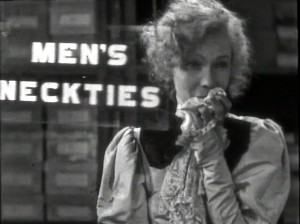

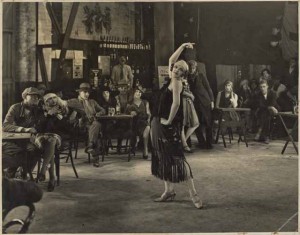

Unfortunately, the majority of Karenne’s productions are presumed lost (Martinelli 142). But, recently, there has been some important archival identification and restoration efforts. In 2022, a three-reel film entitled When Hearts that Loved Each Other Part, with German intertitles, was identified at Gosfilmofond as an incomplete version of Karenne’s Italian debut, Passione tsigana, probably her greatest success. In the film, she played Azara—a gypsy woman who loves freedom, rebellion, sensuality and sentiment—and, according to critics, proved to be particularly photogenic. Thanks to her strongly expressive face, she succeeded in conveying even the subtlest emotions of the protagonist fully. The identified copy includes the first three reels (of the original five). The missing ones have been reconstructed on the basis of the detailed synopsis published in the January 30, 1916, issue of magazine La Cinematografia Italiana ed Estera. It was also recently discovered that Gosfilmofond has a copy of Smarrita!, made in 1921 by Giulio Antamoro and likely based on the work of an exiled Russian writer, Ossip Felyne. Unfortunately, it is missing two reels and has been re-edited. It is catalogued under its Russian distribution title, Maria Grieg (Shvediuk). The Cineteca Italiana in Milan has also recently restored some vintage nitrate sequences from Maria di Magdala,

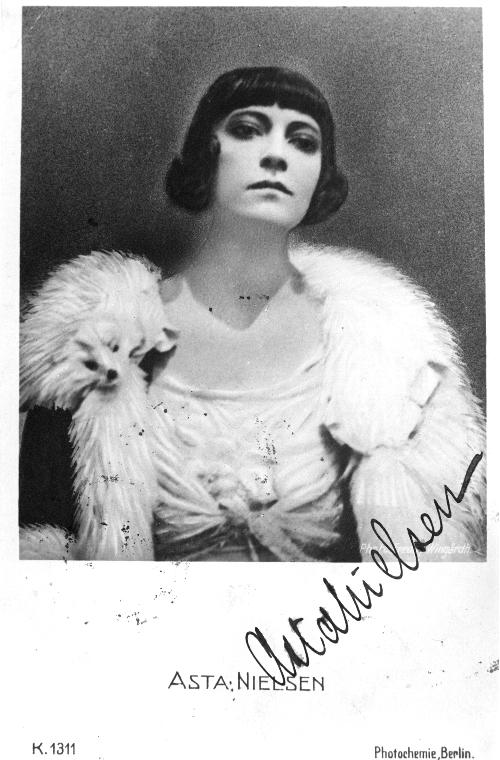

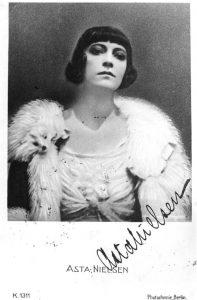

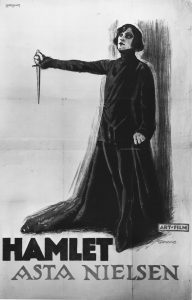

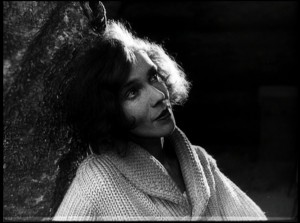

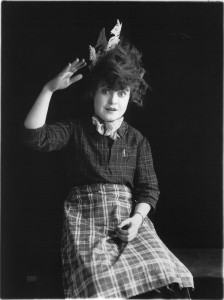

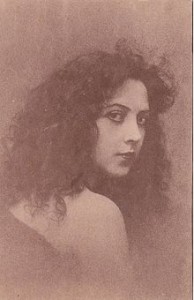

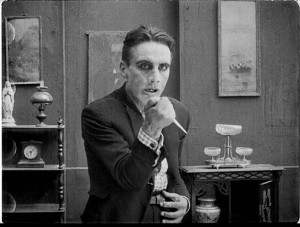

The little we do have in terms of film prints, magazine articles, books, and photographs reveals Karenne’s desire for experimentation, for moving past common patterns, and for breaking with convention, both in the practice of acting and in the representation of female figures on screen. Karenne’s style had a greatly progressive value in the Italian cinema panorama at that time. Her acting style, as far as we can analyze it through her few extant films, emerges as a mixture of naturalism and anti-naturalism and reflects many influences. The melodramatic style of Italian stardom is present, yet it is diluted with realism and a deep sobriety that seems influenced by contemporary Nordic cinema as Asta Nielsen was frequently mentioned by the actress as a model (Martinelli 142). Staginess is more enhanced and the naturalistic style fades into the background only when the dramatic strain in the narrative flairs up. In such occasions of deep and emotional melodrama, Karenne’s style is obviously affected by clear influences of Italian stardom, but mostly by the expressionistic mimic and gestural overacting. Moreover, in her powerful physical portrayal of her characters and her attitude to stylized gestures, we can acknowledge some elements of Soviet acting, which was emerging in that period (Jandelli 2006, 26). Her films also show Karenne’s inborn talent for communicating and her skill at drawing out the expressive potential of the cinematic medium. Moreover, her marked versatility enabled the actress to play different character types with great intensity. A peculiar feature of many of her performances was acting in a double role, where she showcased her brilliant talent.

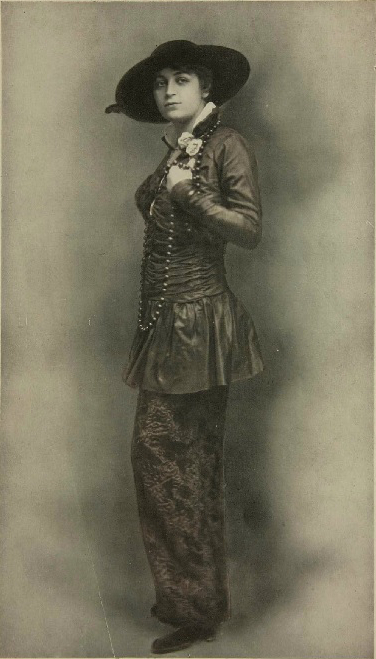

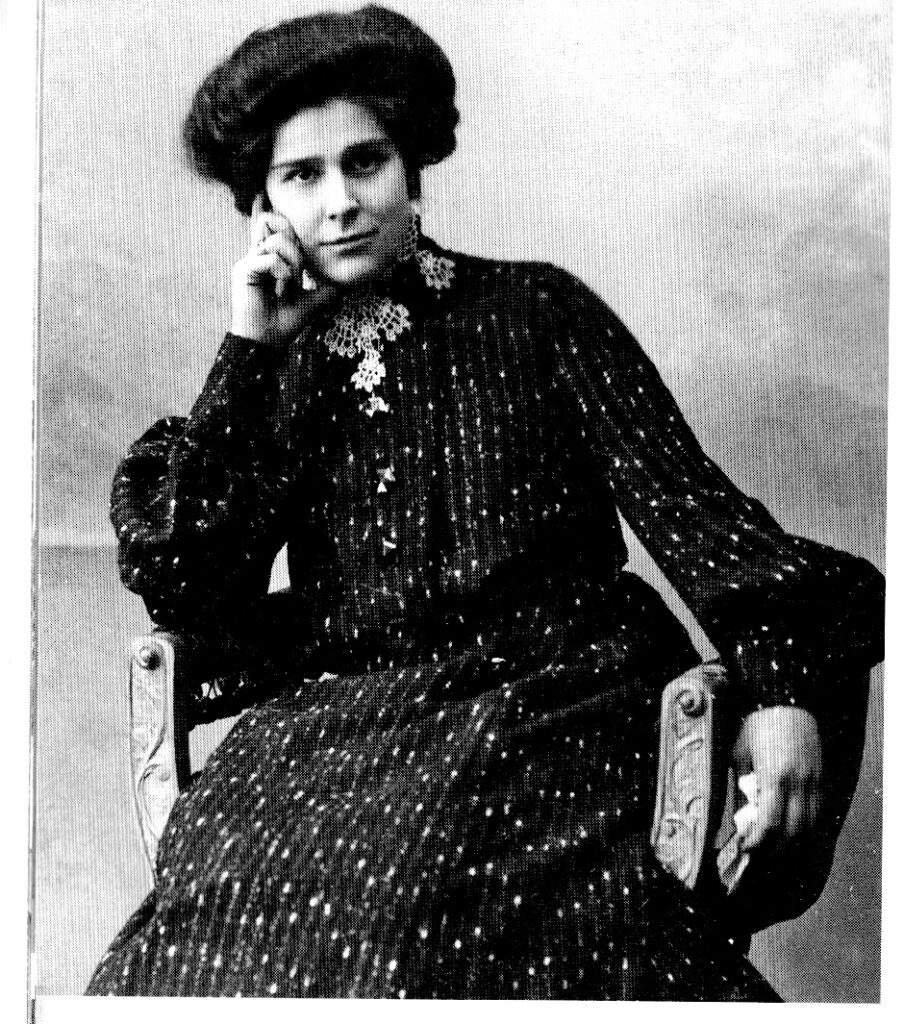

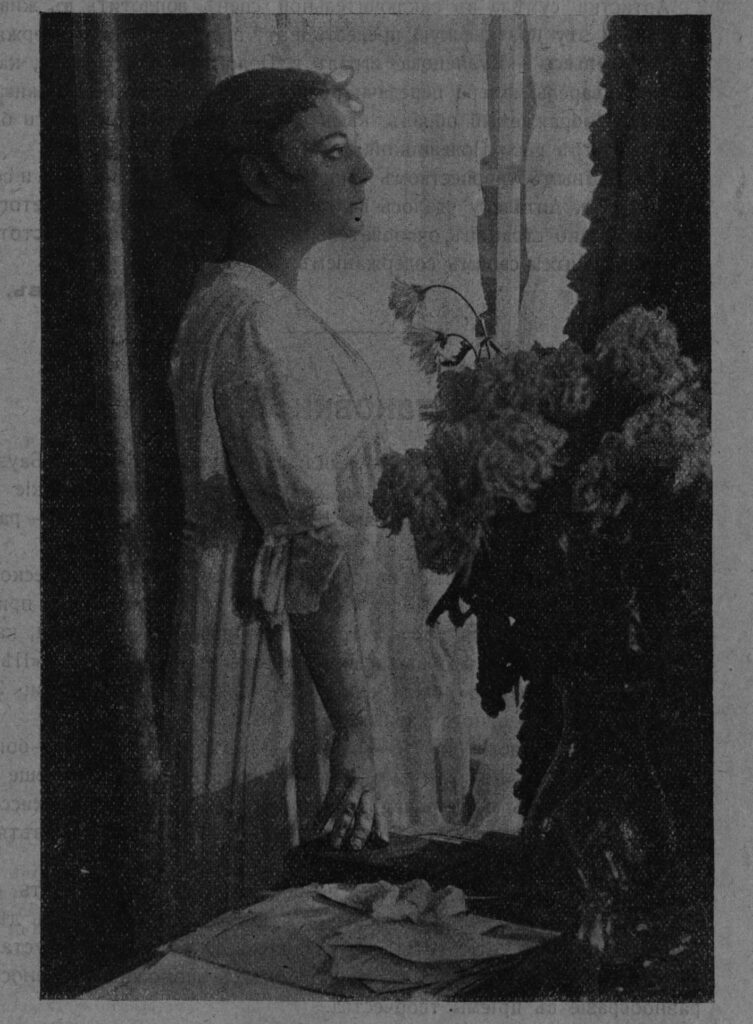

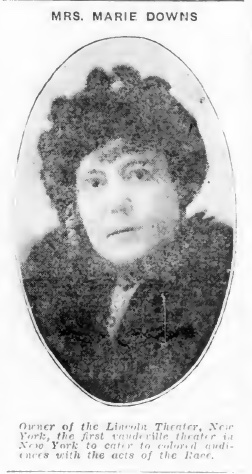

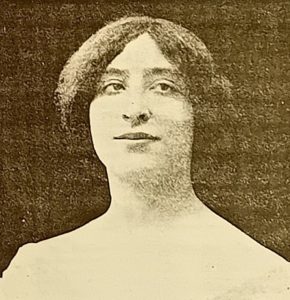

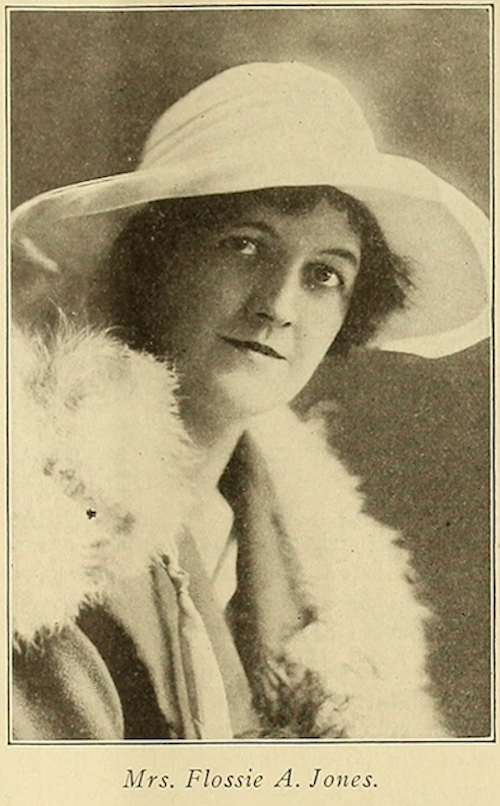

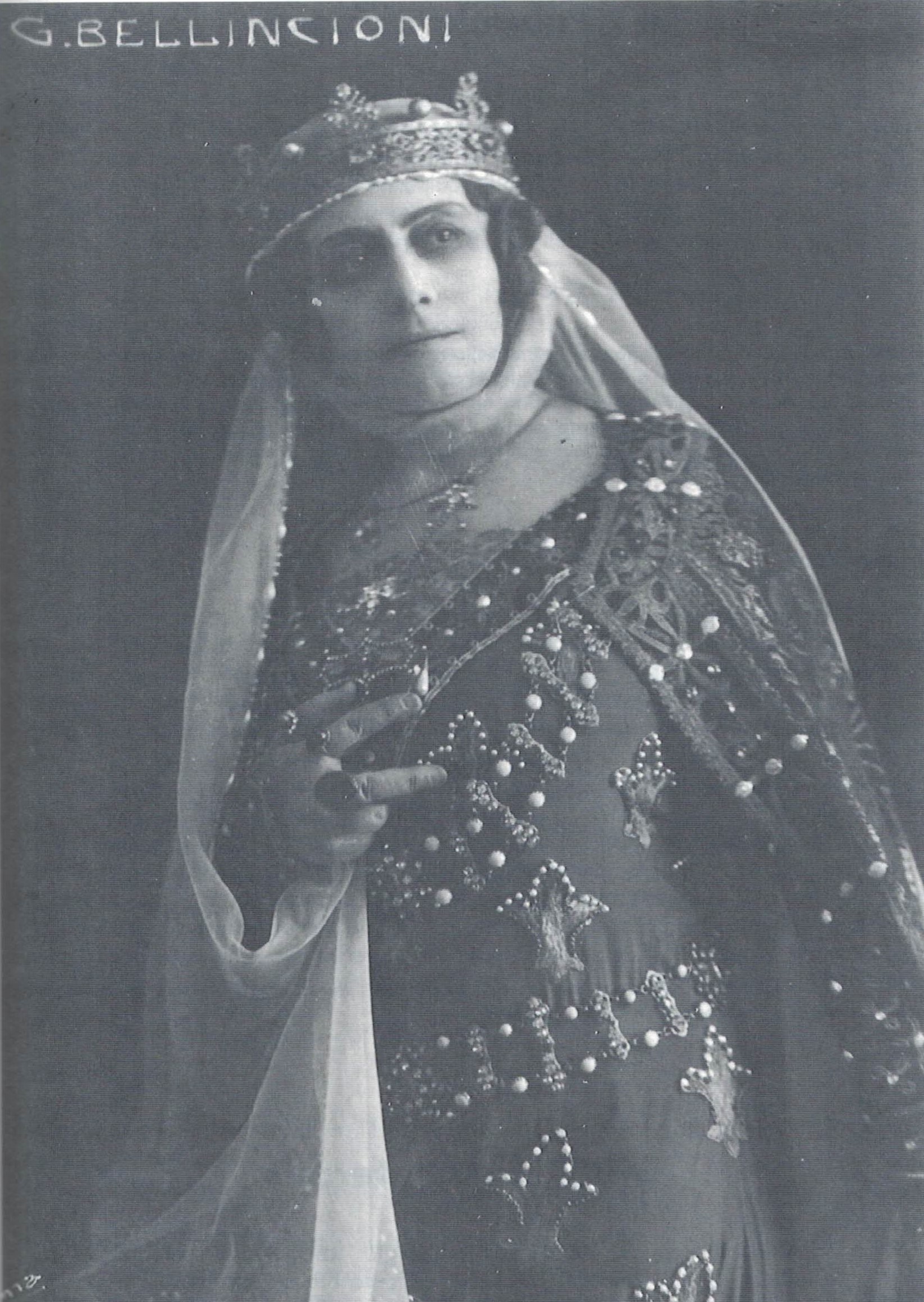

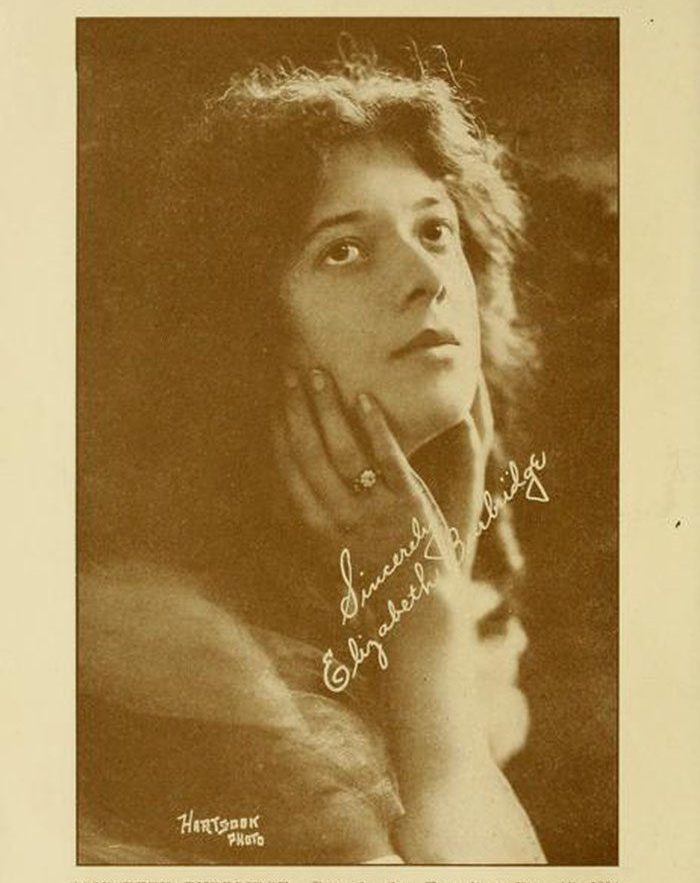

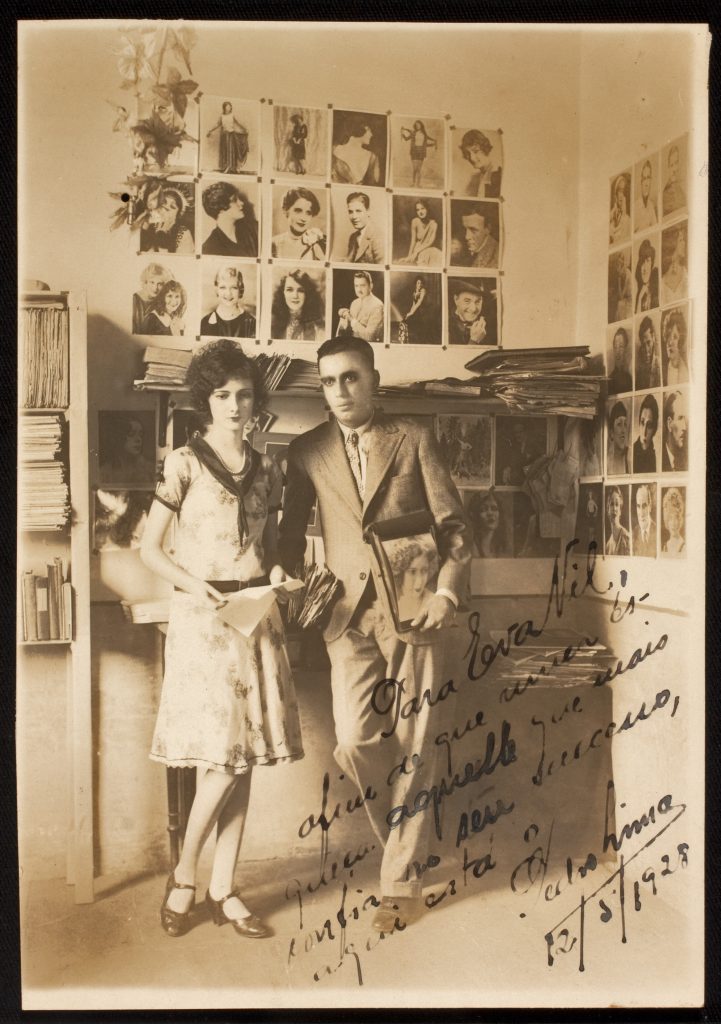

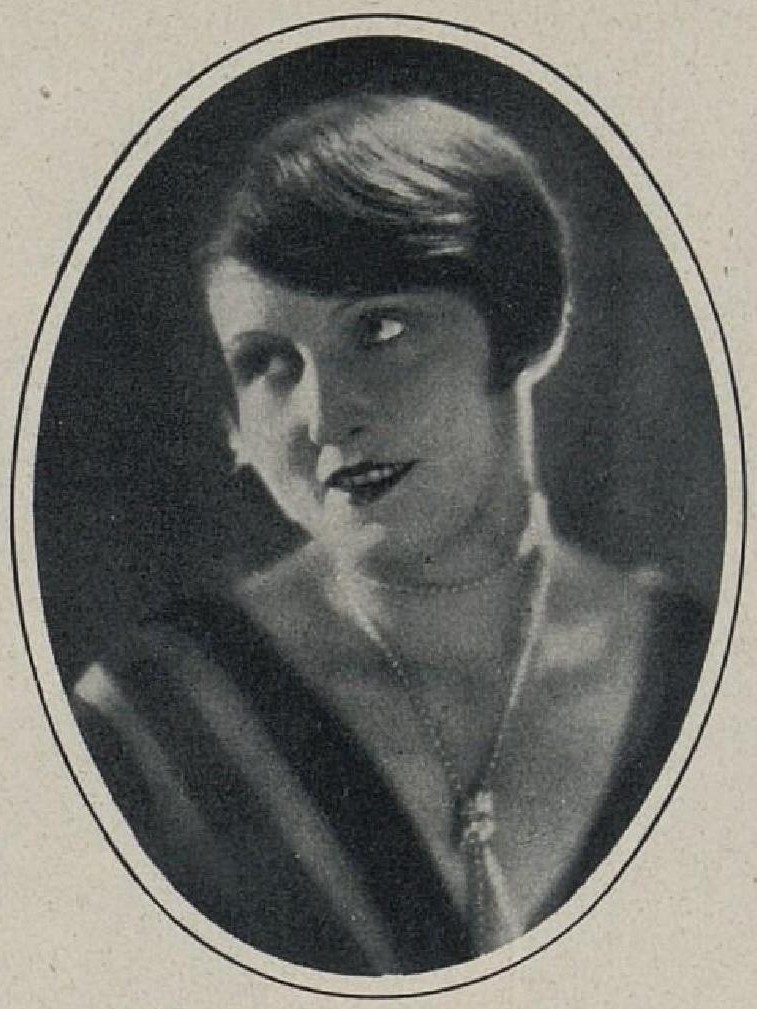

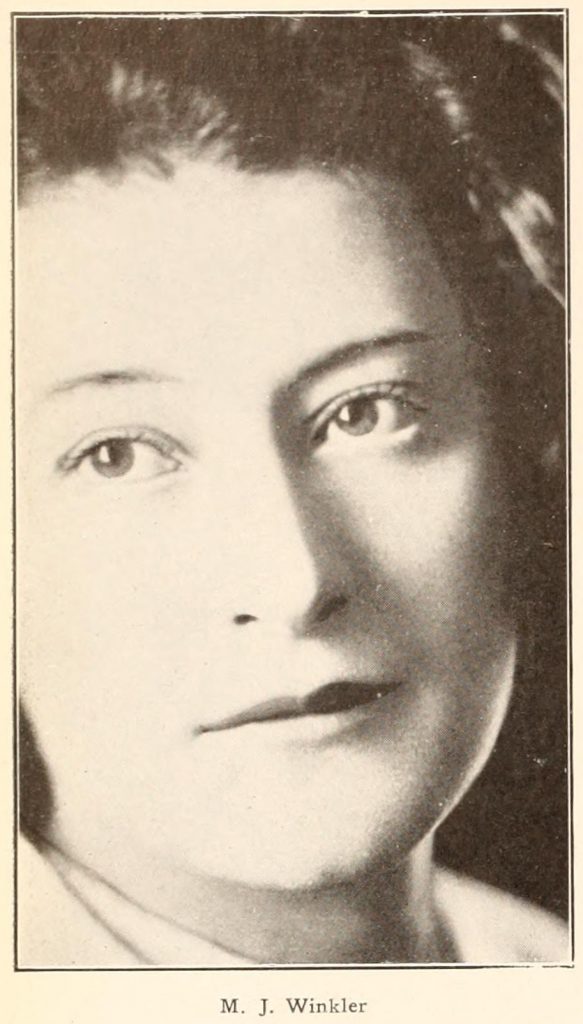

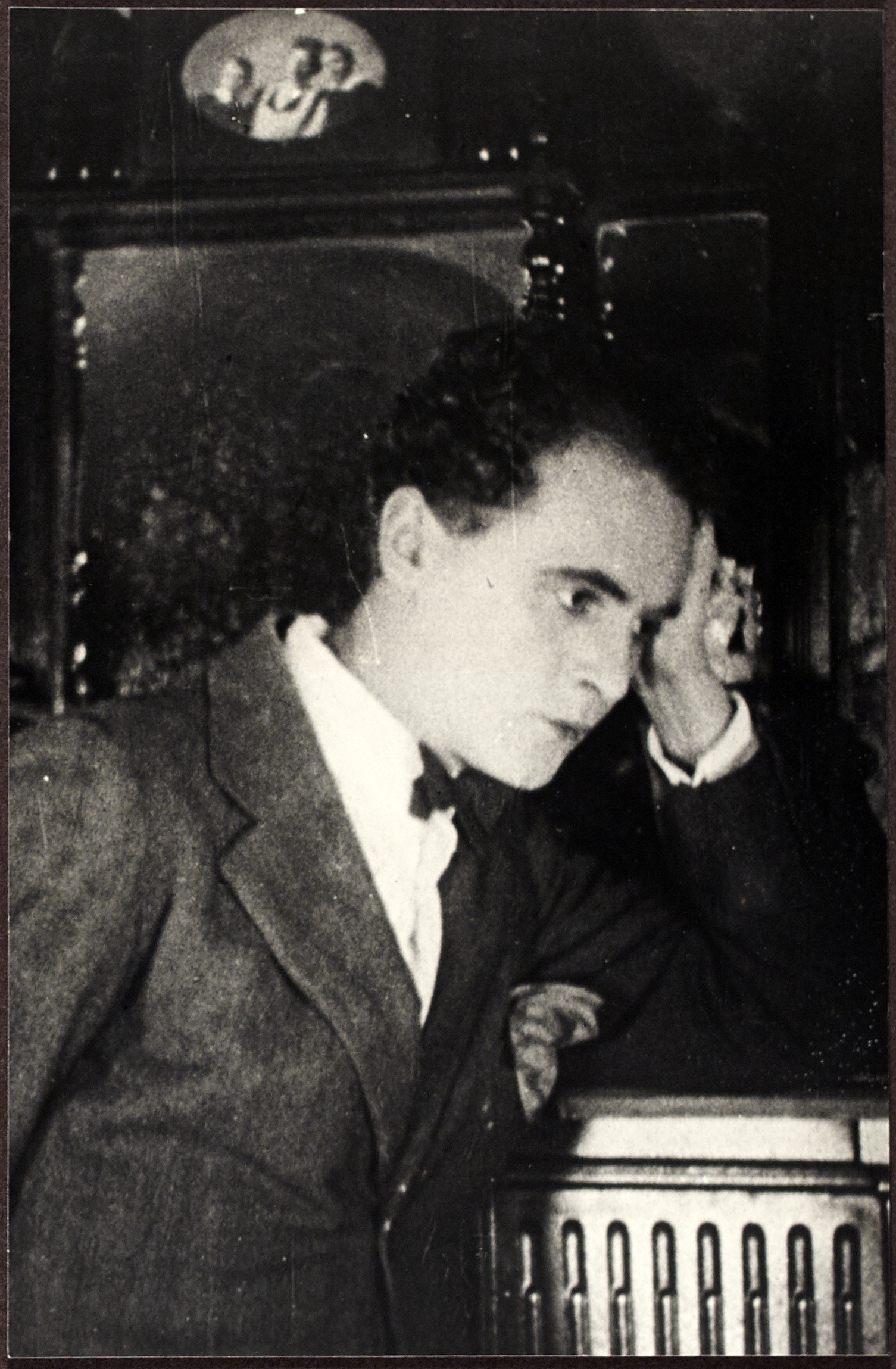

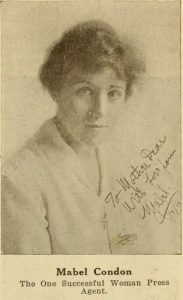

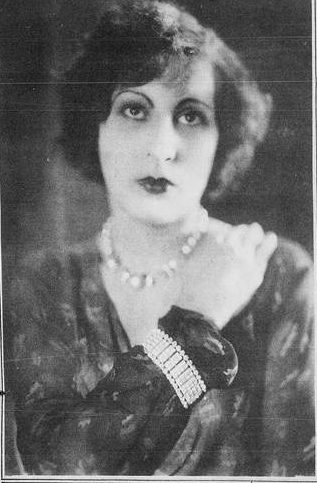

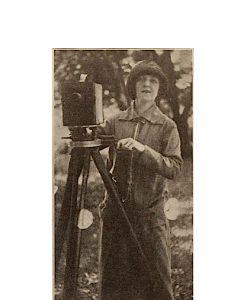

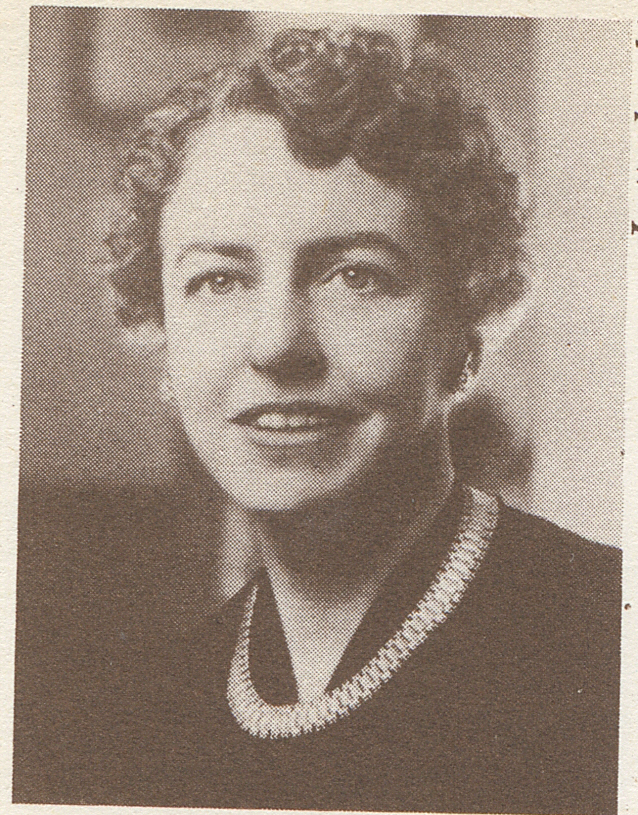

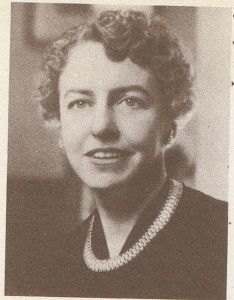

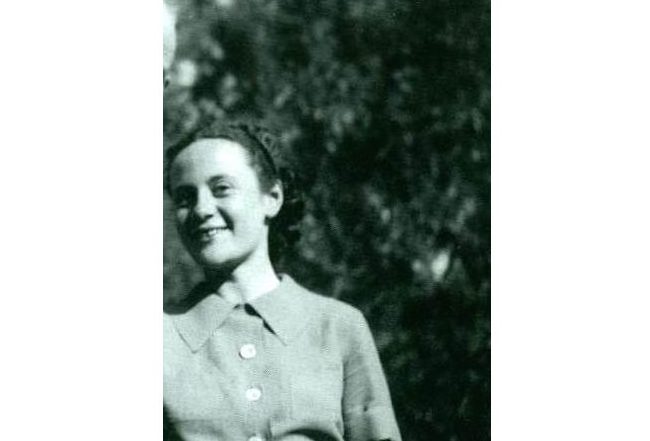

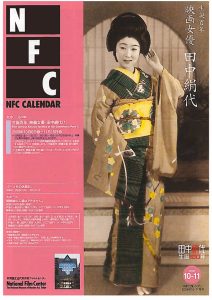

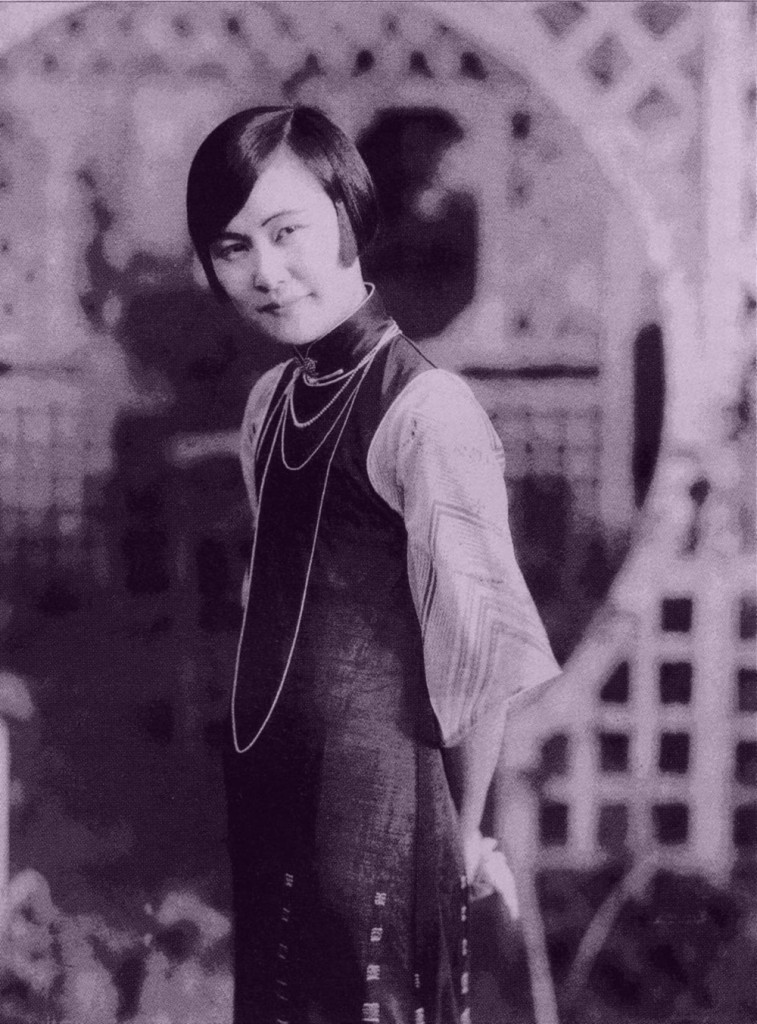

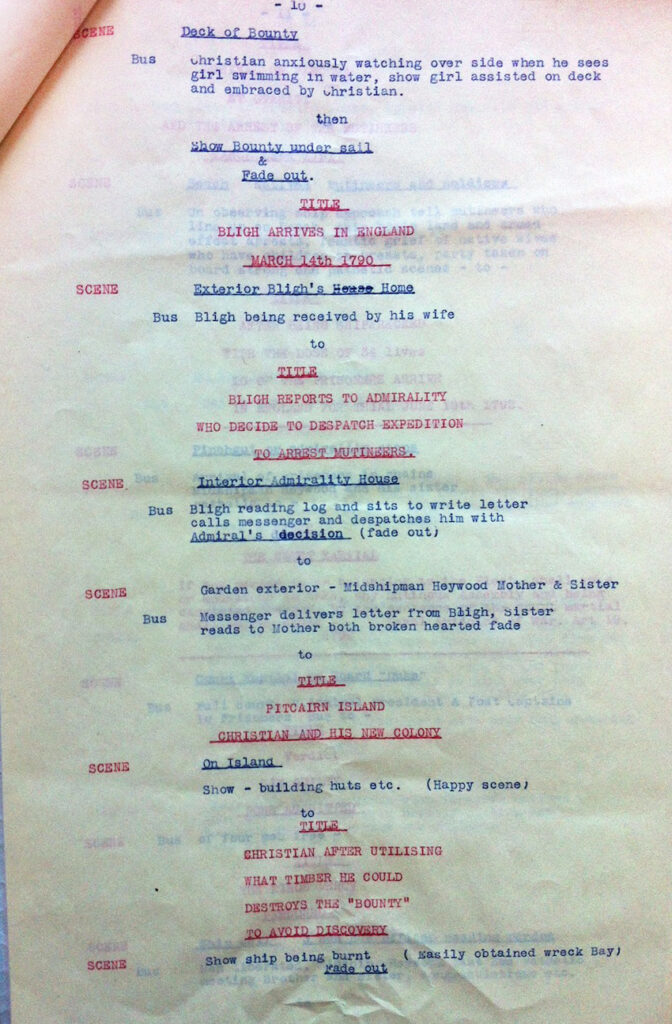

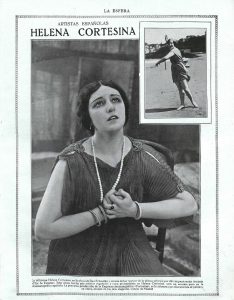

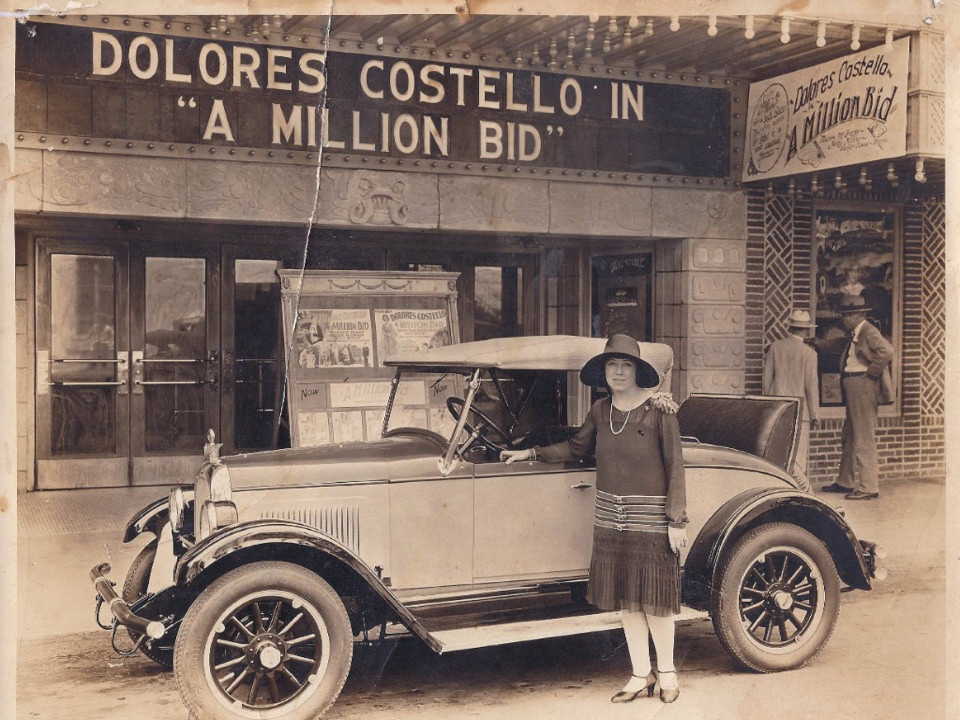

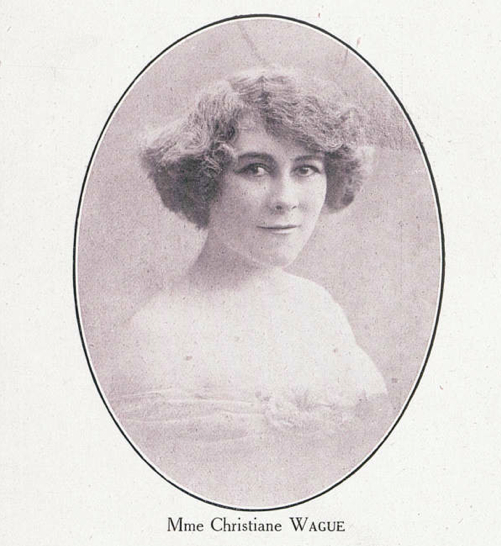

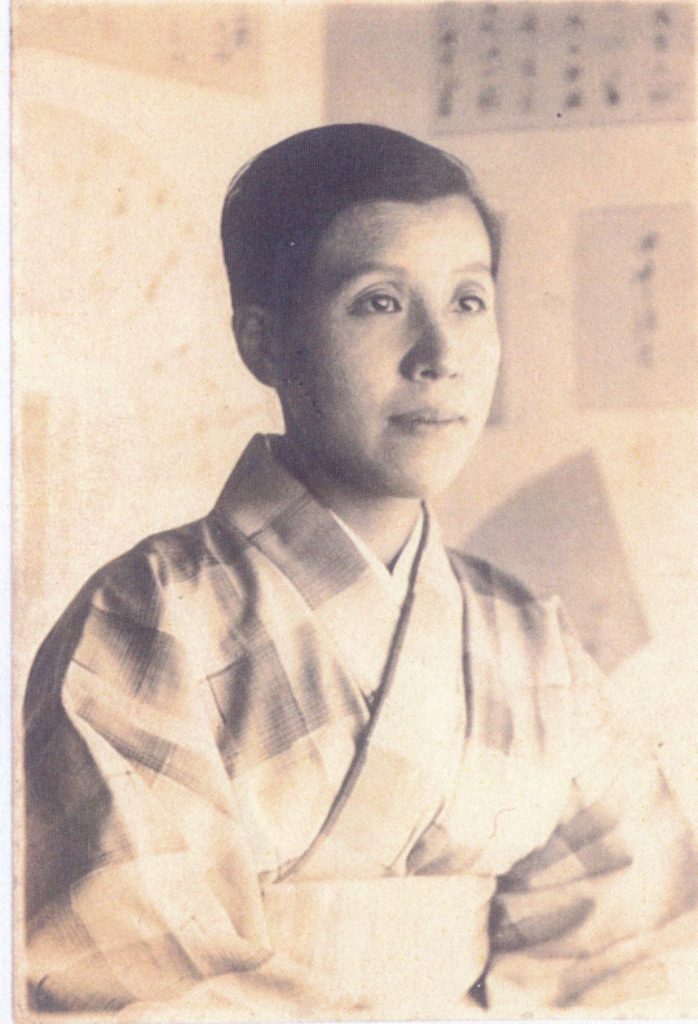

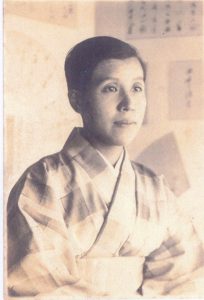

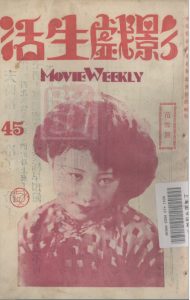

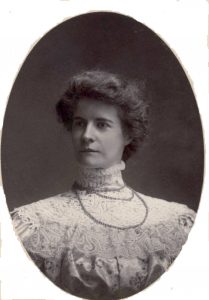

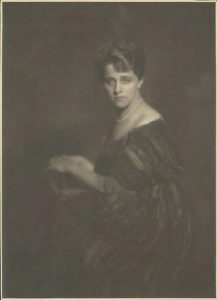

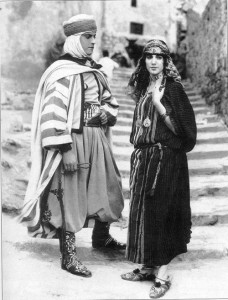

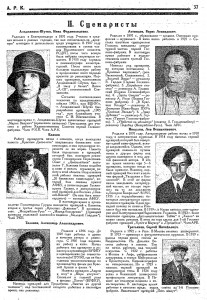

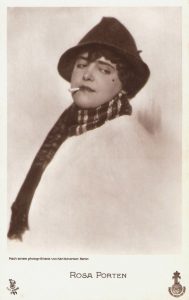

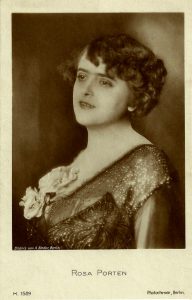

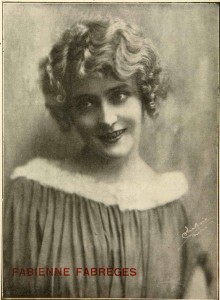

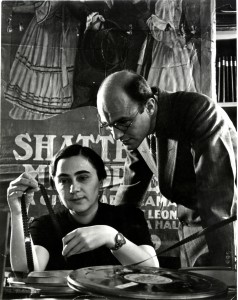

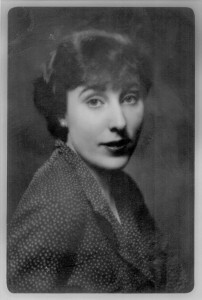

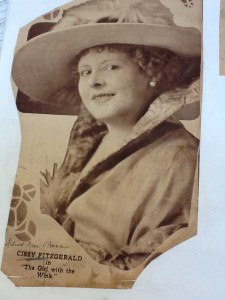

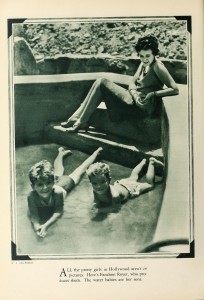

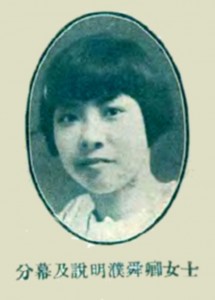

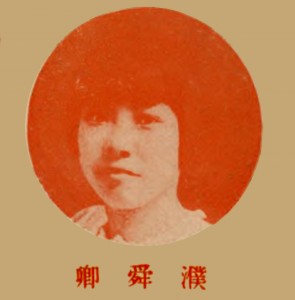

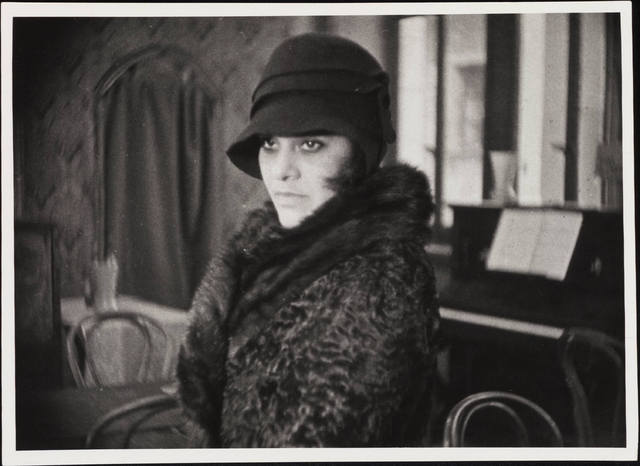

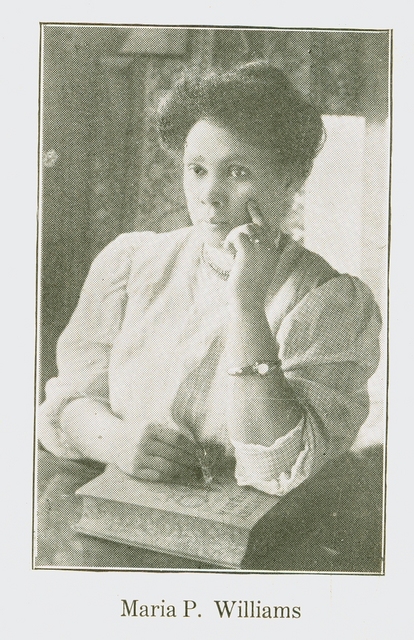

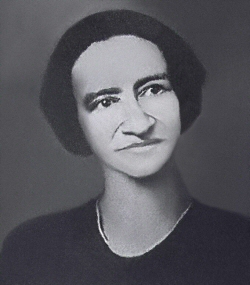

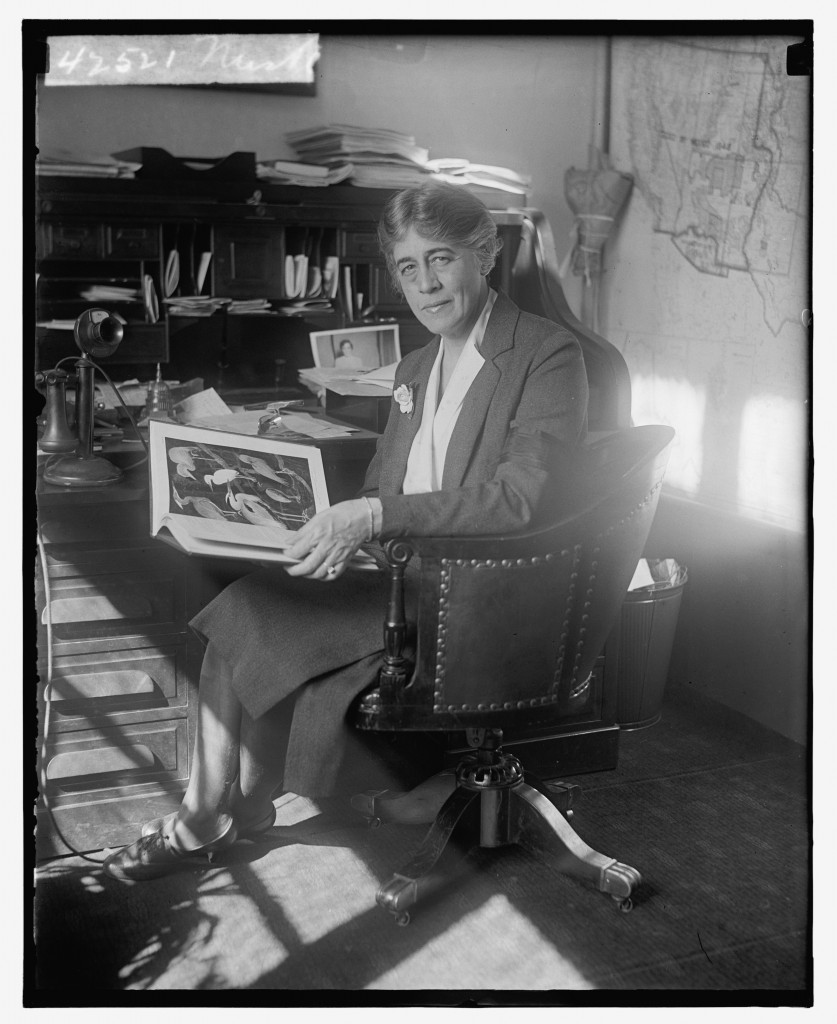

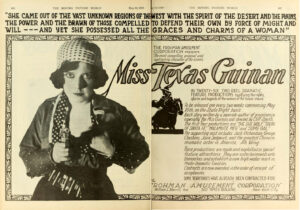

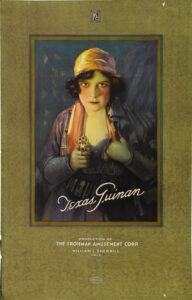

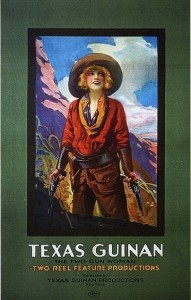

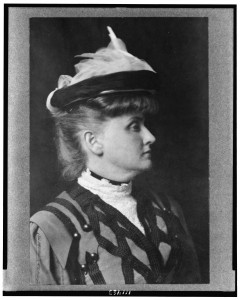

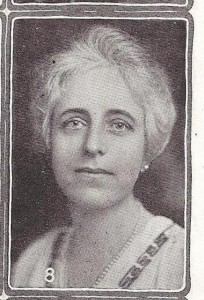

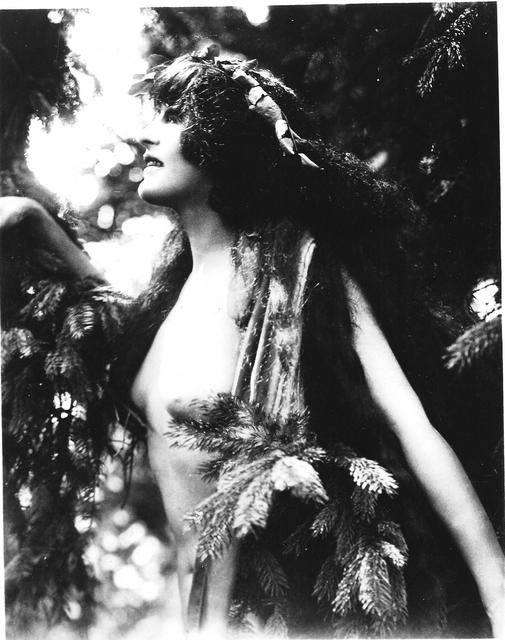

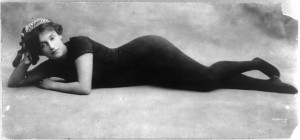

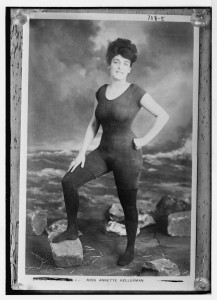

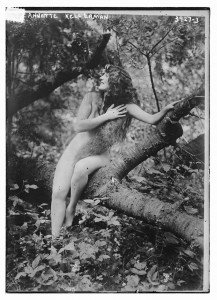

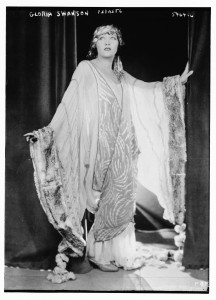

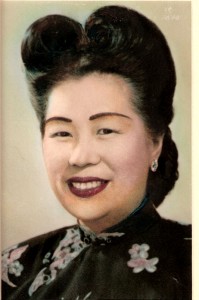

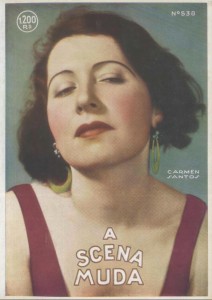

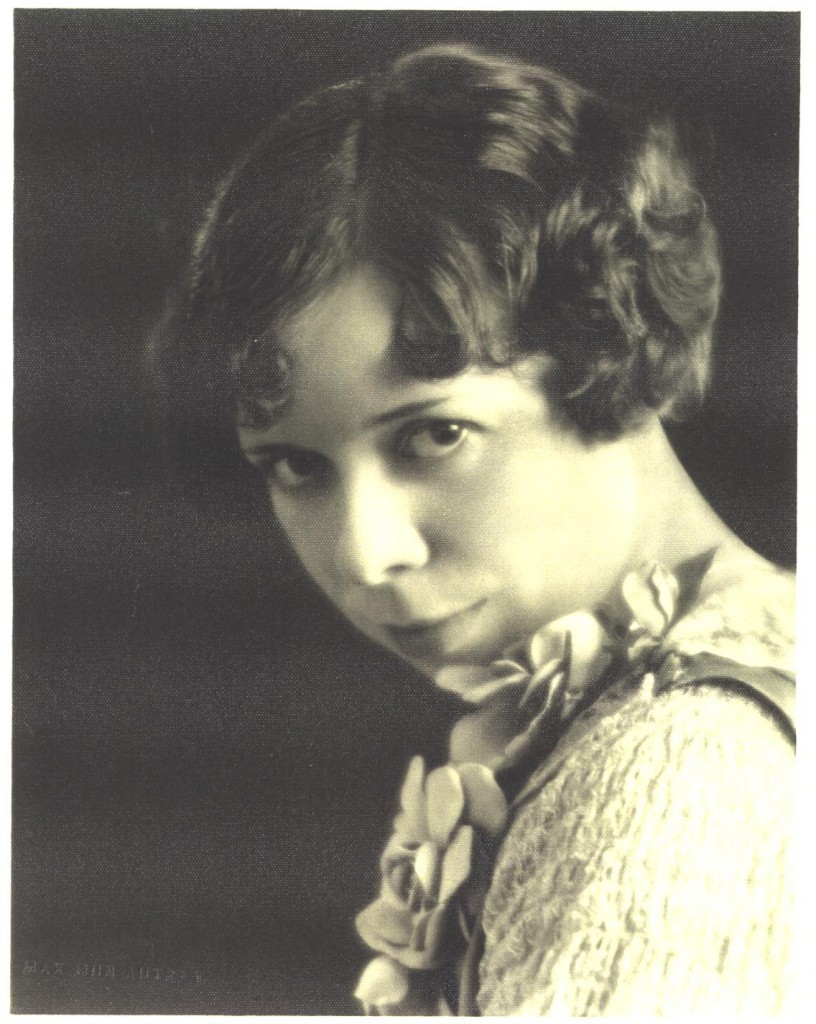

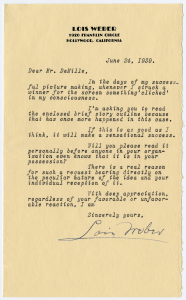

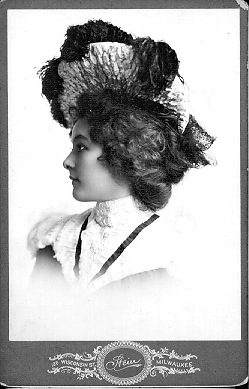

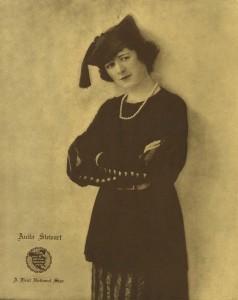

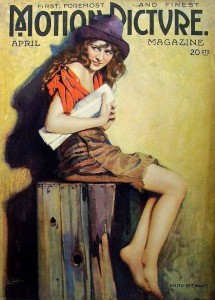

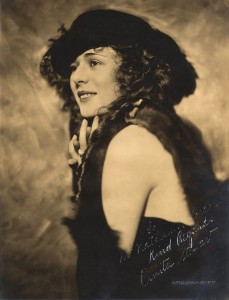

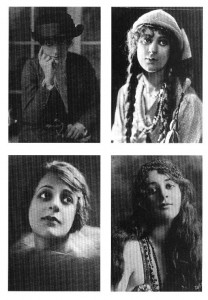

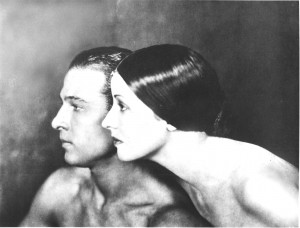

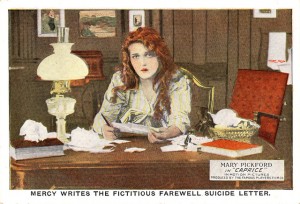

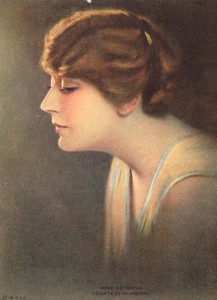

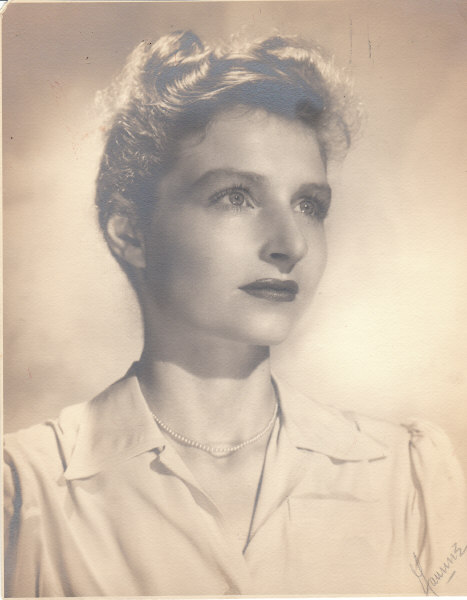

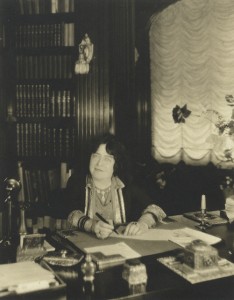

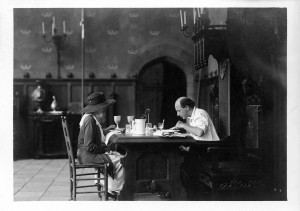

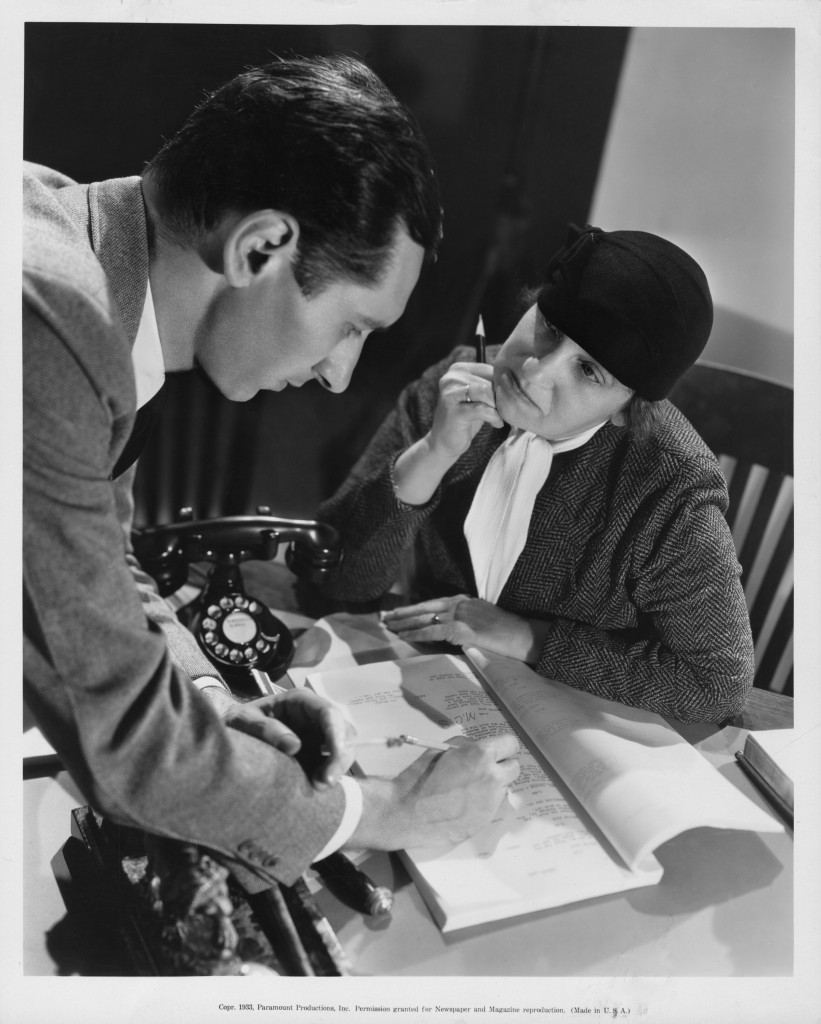

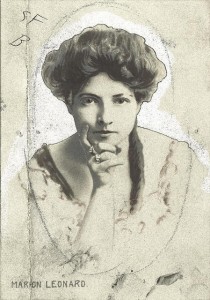

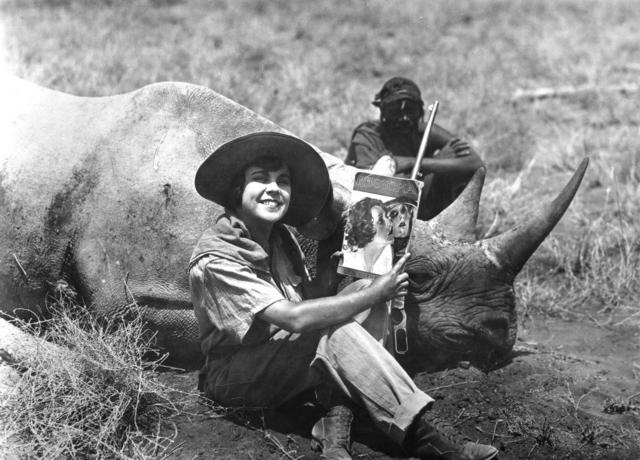

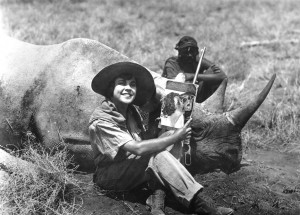

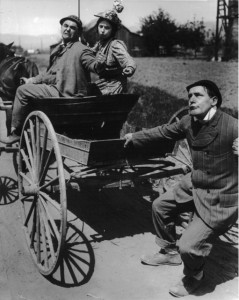

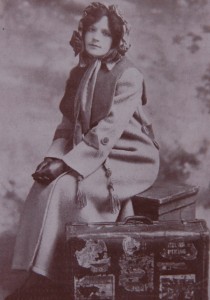

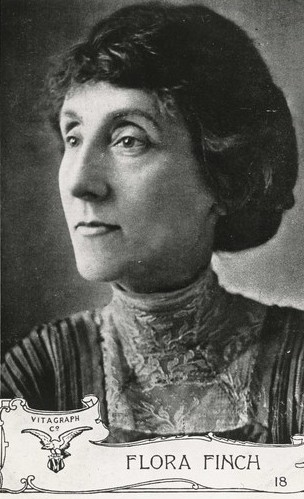

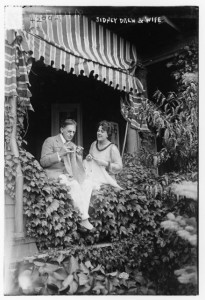

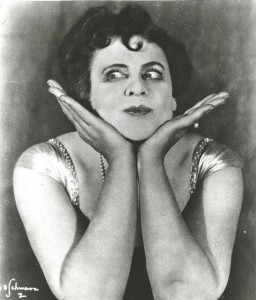

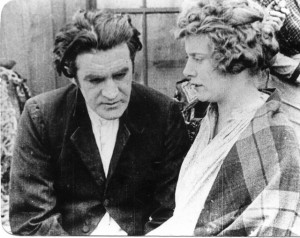

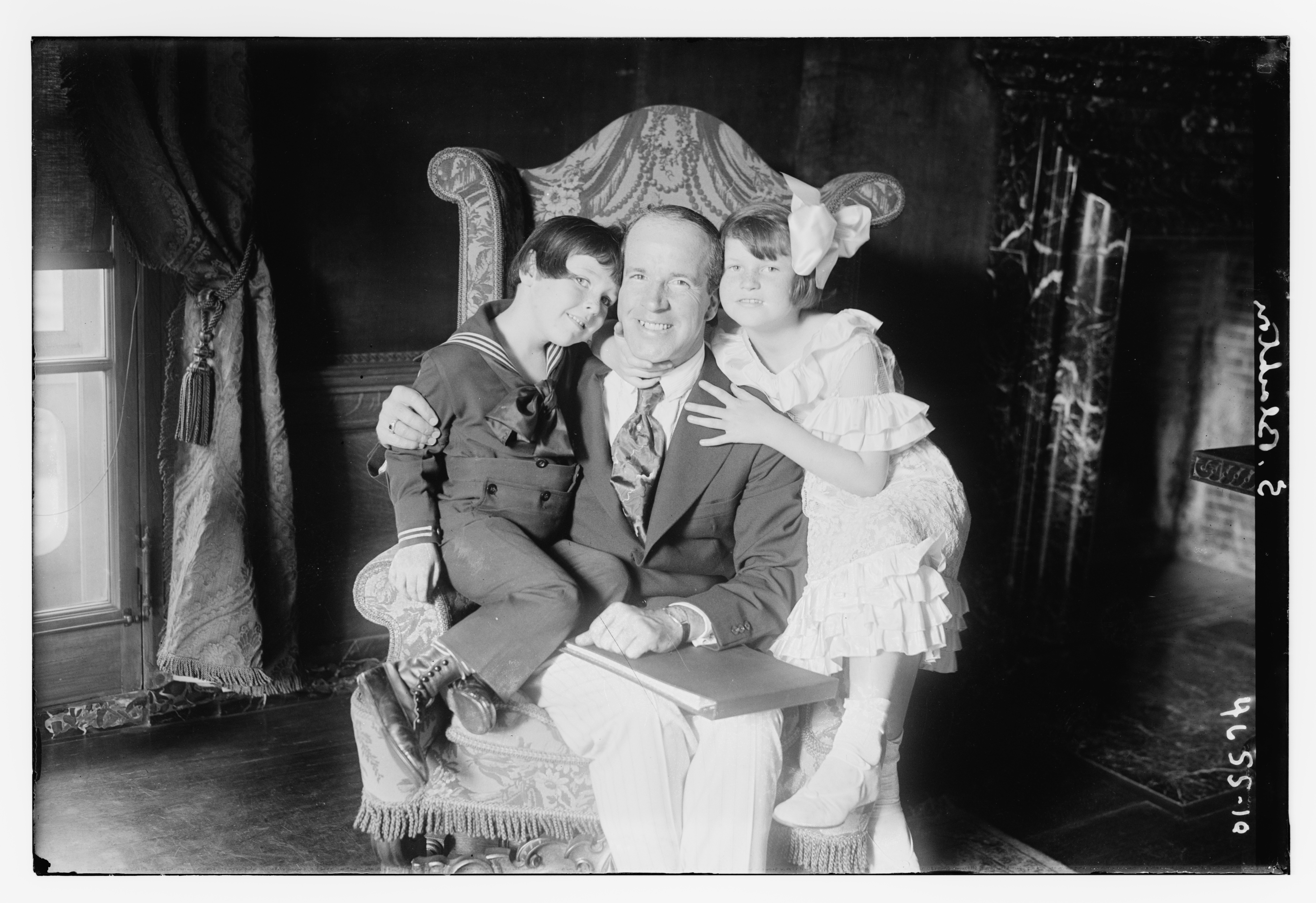

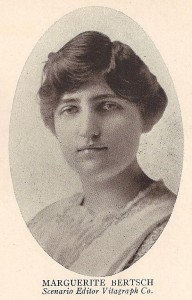

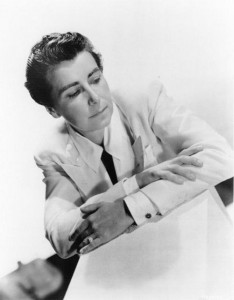

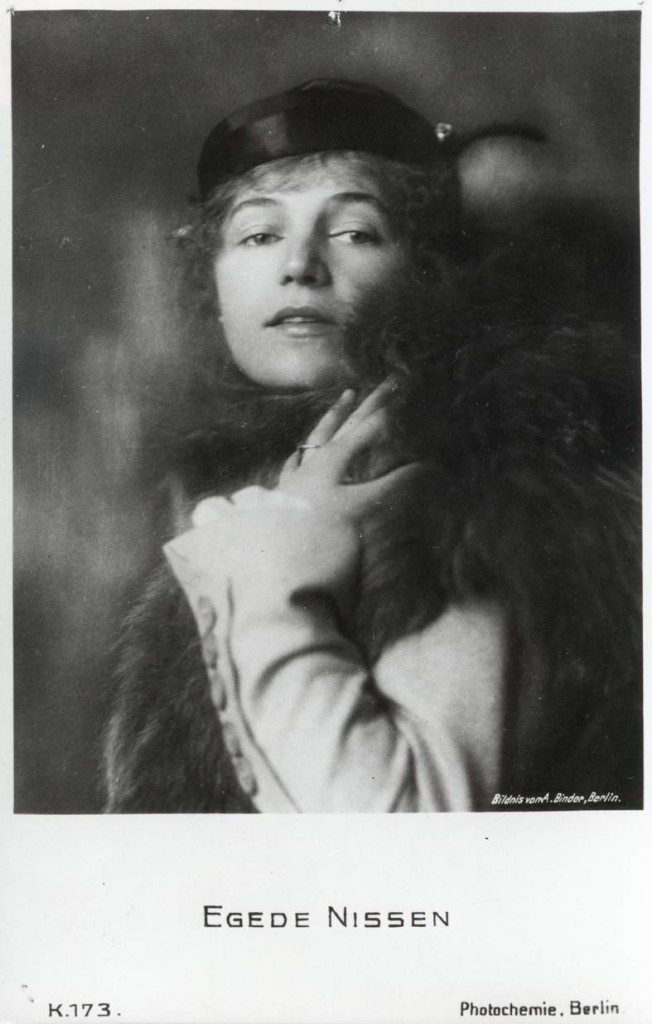

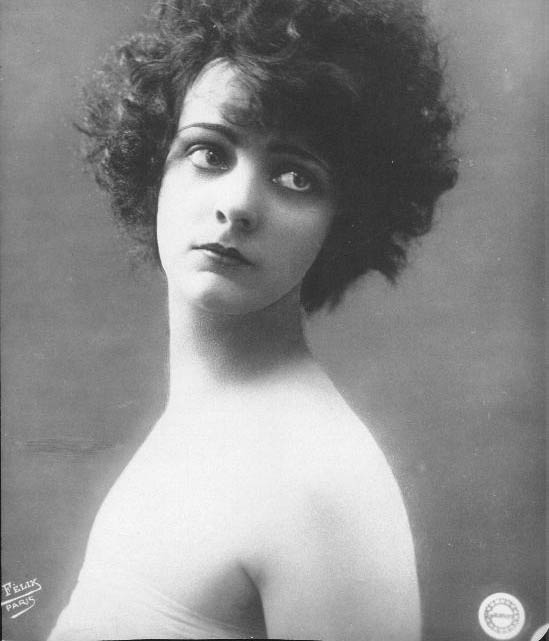

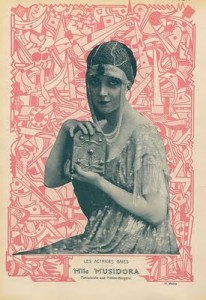

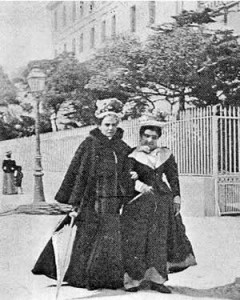

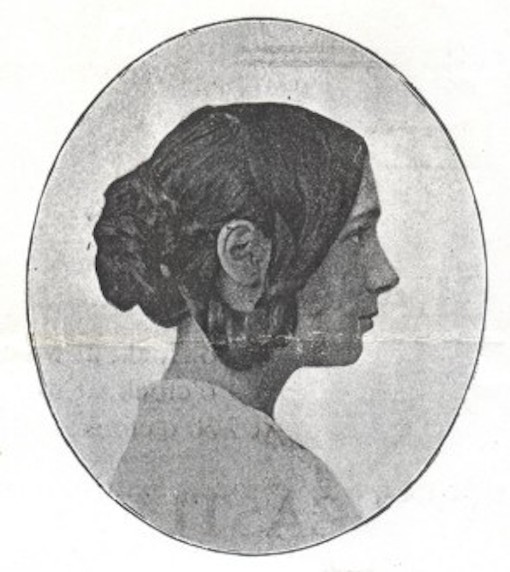

Diana Karenne, 1917. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

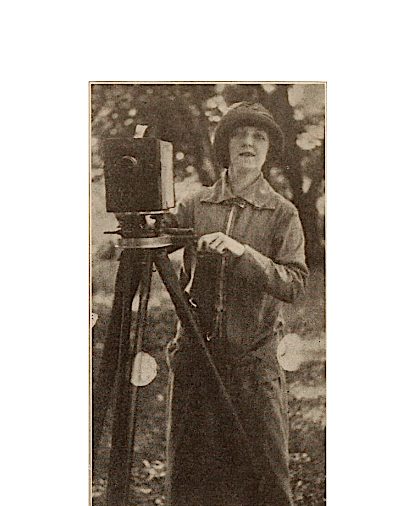

Karenne’s activity behind the camera as director, scriptwriter, and producer is very interesting, even though almost none of the films where she worked in these roles seem to be extant. Her contribution to the establishment of David-Karenne Film and her decision to take over as owner illustrate her unconventionality. It was a daring step, in contrast to the common notion of female professional competence at that time. However, it was exactly in line with the changes in women’s roles that were taking place in Italian society. The 1912 Libyan War and, most of all, World War I, had caused a break with the past from which it was very hard to turn back. Women’s horizons opened wide, making them more and more conscious of their value and giving them more chances for their enterprises. Additionally, the structure itself of the film industry in the early decades, mostly made up of small companies and family businesses, fostered experimentation and female professional achievement: they were not only actresses, but they were also in charge of direction and management (Dall’Asta 2008, 9).

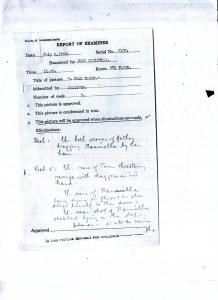

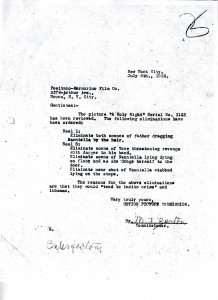

The few sources we have at our disposal present an image of Karenne as a compulsive and whimsical director: she was well-known, according to Cinemagraf in October 1917, for claiming to endlessly shoot a scene until she felt it was perfect (15). As to the characters she used to play on the screen, Karenne seemed to show a preference for female figures with complex personalities: gypsies, adulteresses, murderers, prostitutes, wild girls, masculine or working women and, very often, women who commit suicide (a recurring situation in her films, which was considered outrageous and morally unbearable at that time). Her frequent clashes with censorship and the press can be understood in relation to the modern reach of her characters. Censorship interfered many times with the release of her films because of the subjects treated; film critics often used scornful, misogynist, and sometimes insulting and racist terms on pictures written, directed, and starring Karenne. For instance, Quand l’amour refleurit, the first Italian film Karenne scripted, not only showed a perverse and revengeful lead, but also ends with the girl’s suicide, a conclusion audiences may have found objectionable at that time (Bianchi 192; Jandelli 2006, 212). Even Il romanzo di Maud, directed by Karenne and adapted from Prévost’s novel Les Demi-vierges, ran into serious difficulties with censorship and many scenes had to be cut in order to get a rating to be released. Justice de femme and La damina di porcellana, both directed by Karenne among the early Karenne Film productions, provide us with further examples of unconventional plots and characters. In the former, we find the controversial subject of illegitimate motherhood, while in the latter, the actress plays a life-sized china doll who comes alive and makes her young owner fall in love with her. In La fiamma e le ceneri, written by Karenne along with Gaetano Campanile Mancini, we come across a libertine woman who disguises herself as a beggar just to be received into the house of an organist whom she likes. The trope of the femme fatale is present in Sleima, together with another much-discussed topic: working women. Sleima is the story of a humble and modest girl who works as a mannequin in a fashion store to support herself and her paralyzed mother; when she finds out that she is the illegitimate daughter of Count Dalma, who has seduced and deserted her mother, she decides to take her revenge by becoming a dissolute woman and piling up riches through cheating and violence. All of these characters, as played by Karenne, have in common a slightly feminist connotation. They all engage in a personal fight for individual achievement and rebel against middle-class respectability and moral rules. In doing so, they place themselves as a direct result of a changing female status, and can be understood as models for the aspiring “New Woman” of that time.

In short, Karenne can be regarded as a unique figure in the film scene of her period. She not only helped to spread a modern notion of womanhood and female professional competence, but she also used her advanced artistic skills to back an entirely personal idea of filming and acting. As a prolific actress, director, producer, and screenwriter with a transnational career, she certainly succeeded in an independent way.

Translated by Chiara Tognolotti