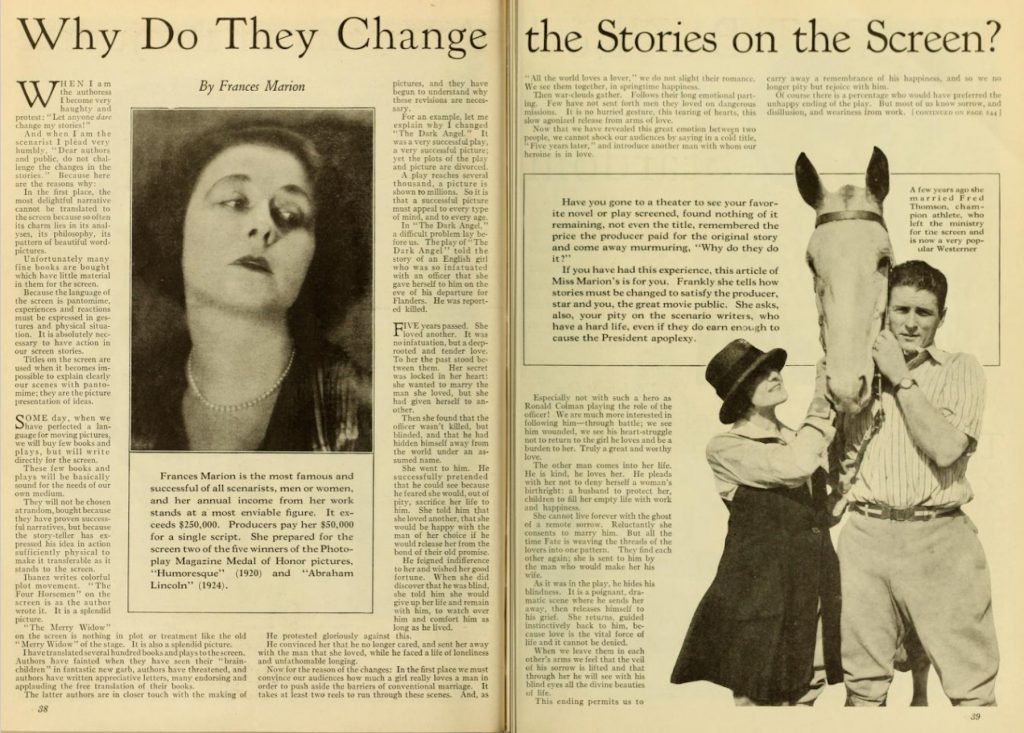

In a 1921 Picturegoer article, Jeanie Macpherson advised prospective writers not to worry about submitting scenarios with scene by scene outlines; instead they should send in a synopsis of 3000 words and a scenario staff would reshape the material for shooting. She warned her audience: “Do not have the camera in mind as you write.”1Jeanie Macpherson, “The Market for Scenario Writers,” The Picturegoer 2, no. 12 (December 1921): 40. In contrast, by 1926 Frances Marion in Photoplay was advising those interested in adaptations to go beyond plot, to translate the original story “into screen language.”2Francis Marion, “Why Do They Change the Stories on the Screen?,” Photoplay XXIX, no. 4 (March 1926): 144. Their different perspectives on how to write for the screen reflected the rapid changes in the craft during Hollywood’s silent period. Women, like Macpherson and Marion, were very much a part of these changes. As Wendy Holliday points out, about 50% of the scenarios were written by women; although, the exact percentage is unknown due in part to inconsistent crediting.3Wendy Holliday, Hollywood’s Modern Women: Screenwriting, Work Culture, and Feminism, 1910-1940 (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1995), 100, 114, 140 (note 49), 144 (note 82). In fact women’s presence was felt in multiple areas of the American film industry including writing, directing, producing, and editing, as the industry initially welcomed, even sought out, their contribution. Women wrote both original and adapted scenarios. In addition, they contributed story ideas, served as story editors and continuity writers, and wrote titles. As department and unit heads, they further impacted the stories being told. Women were everywhere as the craft of screen writing took shape.

With many of the films and scripts from this period lost, scholars have turned to archival sources, such as fan and trade publications, memoirs and biographies, to explore women’s contribution. They have documented women’s work, and have examined both the social and economic forces that influenced women’s entrance into the industry and the gendered context and nature of their work. However, research has been relatively silent on the ways in which these women influenced screen writing as a developing craft. Women writers offered insights on how to write the scenario or shooting script. And while many women met the studio and audience expectations for female-centered narratives, female protagonists and subject matter, they also pushed the boundaries of expectations by crafting strong independent female characters, by refusing to “write to gender,” and/or by producing alternative cinematic forms. During their time in the industry, women helped shape the form and technique of cinematic writing and influenced both its tone and content. They carved a place for themselves in the history of a developing art form.

Advancing the Form

When women entered the industry as “writers,” there was no existing craft to learn as there were no written scripts. Writing for cinema prior to 1912 involved submitting story ideas/plot synopses or writing titles. Ideas and synopses were elicited through magazine advertisements or contests, freely submitted, or written by company staffers. Women were counted among the many early contributors of these “stories,” as gender was not an impediment. Karen Ward Maher notes in Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood that women in all areas of cinematic production “enjoyed low craft and gender boundaries” in the very early days of cinema–a situation that would later change.4Karen Ward Mahar, Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 42. See also Holliday, 18. These early stories took the form of a few lines of text, a paragraph or a one-page plot summary. Producers/directors then took the story from page to screen, while a clerk on set “held the script,” recording scenes, action, dialogue, and shooting directions.5See William K. Everson, American Silent Film (New York: DaCapo Press, 1998), 32; and Tom Stempel, Framework: A History of Screenwriting in American Film (New York: Continuum, 1988), 10-14. These clerks were called script girls, since most were female secretaries or assistants, a testament to the different ways women were tied to early storytelling in Hollywood.

Writing for the screen was attractive to women, both those who freelanced from home (through open submission or writing contests) and those who sought full-time careers. Martin F. Norden in his study of The Moving Picture World articles from the teens explains that the open submission structure was appealing to women bound to the home as it offered them an opportunity “to pursue more creative experiences.”6Martin F. Norden, “Women in the Early Film Industry,” Wide Angle 6, no. 3 (1984): 64. Anne Morey’s study of gender expectations in “fictional” Hollywood also finds that such opportunities allowed women to write without sacrificing their domestic duties or threatening traditional concepts of femininity. See Hollywood Outsiders: The Adaptation of the Film Industry, 1913-34 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 48-49. Maher finds a similar attraction in the company-sponsored contests advertised in popular fan magazines. Her research indicates that most winners of early company contests for the best “story idea” or plot synopsis were women.7Mahar, 41. Such women followed in the footsteps of those women writers who had been contributing stories to popular magazines since the nineteenth century.8For information on women’s contribution to nineteenth century popular magazines, see Donna Rose Casella Kern, “Sentimental Short Fiction by Women Writers in Leslie’s Popular Monthly,” Journal of American Culture 3, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 113-15. Women also were drawn to full careers in the cinema. Cari Beauchamp argues in Creative Screenwriting that writing for the screen appealed to women, as did other jobs in the industry, because “With few people taking the new industry seriously, the doors were wide open to women.”9Cari Beauchamp, “Frances Marion: ‘Writing on the Sand With the Wind Blowing,’” Creative Screenwriting 1, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 56. Though Maher acknowledges the very early opening of the field to women, she disagrees with this “empty field” theory, arguing that “all work emerges from some previously gendered context” (5). Lizzie Francke in Script Girls: Women Screenwriters in Hollywood believes the arts in general, including cinema, offered attractive careers particularly to the white, middle class “New Woman” of the time, “the independent career minded and mostly middle-class females who were striding into the twentieth century.”10Lizzie Francke, Script Girls: Women Screenwriters in Hollywood (London: BFI Publishing, 1994), 6. For many, there was a financial need to work. As Sumiko Higashi explains in Virgins, Vamps and Flappers: The American Silent Movie Heroine, this need successfully challenged the separate spheres model that argued for women’s place in the home. As a result, between 1910 and 1920 women’s presence in the work force increased as did their wages.11Sumiko Higashi, Virgins, Vamps and Flappers: The American Silent Movie Heroine (St Albans, VT: Eden Press, 1978), 96-97. The need for writers in Hollywood, then, emerged at a time when women were looking to expand opportunities, financial and/or creative, beyond the home.

Among the documented early career writers were Edison’s Carolyn Wells who joined the staff as a writer in 1909, according to Lux Graphicus in Moving Picture World.12Lux Graphicus, “On the Screen,” The Moving Picture World 5, no. 11 (11 September 1909): 342. Mary Pickford began her career the same year, writing and acting in both Getting Even (1909) and The Awakening (1909). And Kathlyn Williams started as a writer with The Last Dance (1912), before her run as a serial queen. Gene Gauntier was also one of those early writers. She quickly became a driving force as both an actor and writer for Kalem productions. In “Blazing the Trail,” which first appeared as a serialized article in the 1928 Women’s Home Companion, she explains that though she was hired at Kalem as an actor, she began writing “crude” scenarios in 1907: “A poem, a picture, a short story, a scene from a current play, a headline in a newspaper. All was grist that came to my mill.”13Gene Gauntier, “Blazing the Trail,” Woman’s Home Companion LV, no. 10 (October 1928): 183. Her comments reflect the skeletal nature of early writing. When she first started, stories consisted of outlines with a few words describing each scene: “There was never a scenario on hand.”14Ibid., 181. Like Gauntier, Anita Loos entered the business early; however, Loos focused her career solely on writing. In her 1977 memoir, Casts of Thousands, she explains how she began submitting stories from home, and was only a teenager when she captured the attention of D.W. Griffith. In fact when Loos came to Hollywood to meet him, at his request, he mistook her mother for his intrepid new writer. Loos writes that her first produced story was The New York Hat in 1912, and for the next three years, she turned out over one hundred stories/scenarios. Whatever Biograph rejected went to Vitagraph, Kalem, or Selig.15Anita Loos, Cast of Thousands (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1977), 20-21, 25. Loos admits in an interview with Film Fan Monthly in 1967, however, that what were called scenarios were pretty bare: “As a matter of fact, the films were practically composed on the set.”16“FFM Interviews Anita Loos,” Film Fan Monthly 69 (March 1967): 4.

This assembly line of film production that both Gauntier and Loos identify resulted in early crediting problems that impacted the woman writer. In the absence of detailed scenarios, the final film was often far from the original story idea or plot summary, and the author forgotten. As a result, writing credits typically were either absent or assigned to producers or directors.17See Stempel, 136. Norden also notes that women in the teens were poorly paid and frequently did not receive screen credit. He mentions the case of Grace Adele Pierce who was not credited for adapting Judith of Bethulia (1913) from the Bible, poem, and play. See “Women in the Early Film Industry,” 64. Scholars have explored this early issue, identifying gender bias as a “possible” cause. Jane M. Gaines in “Anonymity: Uncredited and Unknown in Early Cinema” sees the “anonymity” issue prior to 1911 as affecting both players and screen writers. Fan and trade magazines, she explains, eventually called for the crediting of players, but not writers. Though she does not argue for gender as a key factor in early anonymity, she admits that “In the first two decades of the century, anonymous is almost synonymous with the ‘woman’ writer.”18Jane M. Gaines, “Anonymity: Uncredited and Unknown in Early Cinema,” in A Companion to Early Cinema, eds. André Gaudreault, Nicolas Dulac, and Santiago Hidalgo (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 444, 445. Holliday, however, makes this issue the centerpiece of her 1995 dissertation, Hollywood’s Modern Women: Screenwriting, Work Culture, and Feminism, 1910-1940. Uncredited status was linked to women, she argues, because most of the early amateur/freelance screen writers were women, and freelancers were usually not credited.19Holliday, 3, 37, 133, 319, 387. The link between gender and crediting bears further study. This problem only intensified as women took on full-time careers as writers.

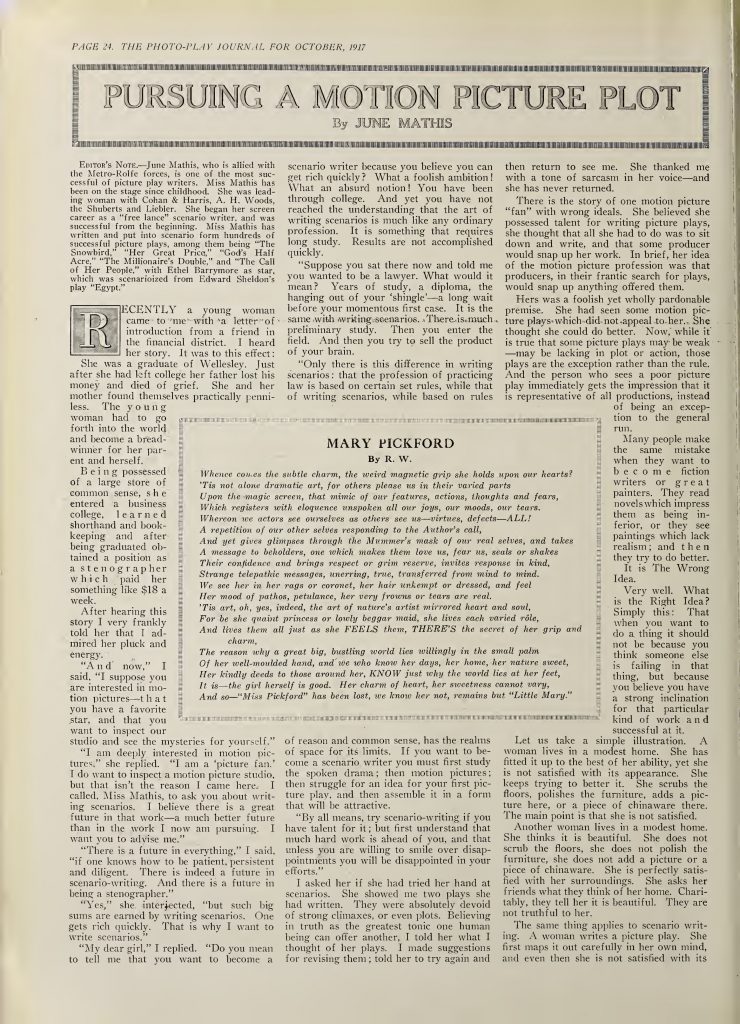

By the mid-teens, the scenario started to take shape as something more than an idea implemented on set by a director. Women contributed to this developing craft by writing more detailed scenarios and instructing on the art itself. Among those women who actively wrote original or adapted scenarios, or both, were Zoë Akins, Hetty Gray Baker, Clara Beranger, Catherine Carr, Russian-born Sonya Levien, Loos, Macpherson, Marion, June Mathis, Bess Meredyth, and Eve Unsell. Jane Murfin adapted her own plays or wrote original scenarios, and Edith M. Kennedy is mentioned in the online AFI catalogue as a story contributor, scenarist, and adapter. Many of these women also advised prospective writers on the continually expanding scenario format. Their advice, which appeared in interviews and in their own written manuals, articles, and books, emphasized the importance of picturizing the material. Carr in The Art of Photoplay Writing (1914) asserts the need to visualize an action and even an emotion. This, she says, will produce “a human interest story.”20Catherine Carr, The Art of Photoplay Writing (New York: H. Jordan, 1914), 9. Mathis in The Photo-Play Journal in 1917 explains, “In your mind’s eye you must visualize your plot, just as you would stand on a mountain-top and gaze at beautiful scenery surrounding you. You must visualize your characters…You must see your characters.”21June Mathis, “Pursuing a Motion Picture Plot,” The Photo-Play Journal II, no. 6 (October 1917): 25. Marguerite Bertsch in her book How to Write for Moving Pictures (1917) also provides detailed descriptions of what goes into a scenario and models for aspiring writers. Scenarios, she explains, must include a title, the number of reels, a one paragraph synopsis, a cast, a list of scenes, a list of props, and a detailed summary of each scene including its setting, character action, and maybe some dialogue.22Marguerite Bertsch, How to Write for Moving Pictures (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1917), 32-130; see also Carr, 51-74. By 1920 Loos and John Emerson in How to Write Photoplays were telling prospective writers to add descriptive subtitles and visual aids for the director, like telegrams or letters.23John Emerson and Anita Loos, How to Write Photoplays (New York: James A. McCann, 1920), 15, 35, 38-41. Writing for the screen had evolved well beyond the initial story ideas or plot summaries.

“Pursuing a Motion Picture Plot” by June Mathis. Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library.

The need to bridge the gap between page and screen and to include the business end of film production led to further changes in the scenario and to the birth of the continuity or shooting script. Women again were on the frontlines. Janet Staiger, in “Blueprints for Feature Films: Hollywood’s Continuity Scripts,” argues that between 1908 and 1917 the increase in film length (more reels) and the desire for well-made films with narrative fluidity resulted in a shift prior to production “from the scenario script to the continuity script.”24Janet Staiger, “Blueprints for Feature Films: Hollywood’s Continuity Scripts” in The American Film Industry, ed. Tino Balio (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 177. In “Dividing Labor for Production Control: Thomas Ince and the Rise of the Studio System,” Staiger explains that continuities added the following to a scenario: director, cast and actors, locations, detailed mise-en-scene, intertitle placement, shooting schedule, budget, and distribution plan.25Staiger, “Dividing Labor for Production Control: Thomas Ince and the Rise of the Studio System,” Cinema Journal 18, no. 2 (Spring 1979): 20 Women, like Beranger, Sada Cowan, Beulah Marie Dix, and Meredyth, were among the many continuity writers. However, it was Mathis and Ince at Metro who developed continuity scripts as the backbone of production. According to Lewis Jacobs “they can be credited with the make-up of continuity as we know it today.”26Lewis Jacobs, The Rise of the American Film: A Critical History (New York: Columbia University, Teachers College Press, 1967), 328.

Women also penned titles well before the continuity script came into play and instructed on the aesthetic of this new practice. Among the first title writers were women like Lenore Coffee, Katharine Hilliker, Loos, and Dorothy Yost. As Bertsch explains in her 1917 how-to book, title writing provides information on action, sets, and character emotion, and includes character dialogue, the latter a recent addition. She even advises on the art of title writing: “We must seek in our subtitles that harmony with our picture which causes them to heighten the action, bring out or express its underlying meaning or atmosphere;–all in that unobtrusive way which makes them part and parcel of the effect in toto.”27Bertsch, 74-83. See also Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By…(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), 82, 295-97. Titling was a natural transition from story writing for women like Loos. As she notes in Kiss Hollywood Good-By (1974), Griffith shelved many of her early scenarios because they contained written dialogue. He believed that “people don’t go to the movies to read.”28Loos, Kiss Hollywood Good-By (New York: Viking, 1974), 7. He changed his mind when he saw the reception for her titled 1916 His Picture in the Papers.29 Ibid., 7-10. As story, scenario, and title writer, Loos witnessed all aspects of the developing craft. According to her 1968 interview with Kevin Brownlow, Loos was Biograph’s scenario department.30Brownlow, 275.

As screen writing was codified as a respected profession, women were represented in all areas of writing in all the major studios. Epes Winthrop Sargent in his 1914 The Moving Picture World article, “The Literary Side of Pictures,” notes the following women writers and their studios: Baker (Bosworth), Carr (Vitagraph and North American), Beta Breuil (Vitagraph), Peggy O’Neil (Vitagraph), Bertsch (Vitagraph), Maibel Heikes Justice (Selig), and Mary Fuller (Edison).31Epes Winthrop Sargent, “The Literary Side of Pictures,” The Moving Picture World 21, no.2 (11 July 1914): 202. According to John William Kellette that same year, Elizabeth Lonergan had worked at Biograph, Kalem, and Majestic.32John William Kellette, “Makers of the Movies: The Lonergans,” The Moving Picture World 21, no. 11 (12 September 1914): 1498. Marion also was starting out at this time. By 1914 she was involved in all aspects of production as Lois Weber’s assistant at Bosworth. She then moved briefly to the smaller Balboa in 1915 hoping to write, finally settling in at Famous Players where she began scripting for Pickford.33See Beauchamp, Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood (New York: Scribner, 1997), 36-37, 41, 44. Sought after for her writing skills, Marion worked throughout the 1920s for a number of companies, including Norma Talmadge Productions, Goldwin Pictures (eventually Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer), and Fox Films. Macpherson, who acted before she took to writing in 1915, regularly contributed stories and adaptations for Jesse L. Lasky, prompting Alice Martin in 1916 to call her the “left half of Cecil de Mille’s brain.”34Alice Martin, “From ‘Wop’ Parts to Bossing the Job,” Photoplay X, no. 5 (October 1916): 95. By 1919 Unsell had already worked with Pathé, Kalem, Universal, Metro, Triumph, and Famous Players-Lasky, according to a writer with the initials M.H.C. in The Picture Show.35M.H.C. (May Hershel Clarke). “Introducing Eve Unsell. Famous Scenario Writer Chats on Photo-Plays and Players,” The Picture Show 1, no. 25 (18 October 1919): 12.And a 1923 Photoplay article, “How Twelve Famous Women Scenario Writers Succeeded in This Profession of Unlimited Opportunity and Reward,” lists Beranger, Ouida Bergère, Cowan, Dix, Marion Fairfax, Loos, Marion, Mathis, Murfin, Olga Printzlau, Margaret Turnbull, and Unsell as actively working in the industry. The article notes that these women “have caught the trick of writing and understand the picture mind.”36“How Twelve Famous Women Scenario Writers Succeeded,” Photoplay XXIV, no. 3 (August 1923): 31-33. Fan magazines found women’s accomplishments noteworthy, as companies jockeyed for their skills.

Women’s readiness to handle the complex art of writing for the screen is not surprising. Most career women joined the field from acting and/or related professions. Bergère began as a stage actor, and Beranger, Marion, and Printzlau were newspaper and/or magazine writers. Novelists and playwrights included Dix, Murfin, Turnbull, and Unsell.37Ibid., 31-33. Justice was a fiction writer, Marian Lee Patterson a magazine writer, and Baker a law librarian.38See Sargent, “The Literary Side of Pictures,” 202. Carolyn Lowry in her 1920 First One Hundred Noted Men and Women of the Screen notes that Fairfax was a stage actor and dramatist, Mathis a stage actor and magazine fiction writer, and Weber a soprano and stage actor.39Carolyn Lowry, The First One Hundred Noted Men and Women of the Screen (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1920), 52, 118, 190. https://archive.org/details/firstonehundred00lowrgoog. Loos was also a stage actor, a profession that bored her so much she started writing film plots.40See Loos, Cast of Thousands, 23 Adele S. Buffington was a cashier at a movie house prior to writing horse operas at Fox, and Isabel Johnston was a journalist and book editor before writing for Vitagraph.41See Francke, 25; and Ann Martin and Virginia M. Clark, eds., What Women Wrote: Scenarios 1912-1929 (Frederick, MD: University Publications of America, Cinema History Microfilm Series, 1987), 22. English fiction writer Elinor Glyn was recruited by Famous Players-Lasky in 1920 to write original film stories and to supervise their production. Scottish-born writer Lorna Moon was living in Minneapolis as a journalist when she was recruited by Cecil B. DeMille. Canadian-born Nell Shipman was a stage actress before writing scenarios and starting her own company in the US where she produced, directed, and wrote wilderness films.42See the following: Anthony Glyn, Elinor Glyn: A Biography (London: Hutchinson, 1955), 273-74; Richard de Mille, My Secret Mother Lorna Moon (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1998), 176-77; and Nell Shipman, The Silent Screen & My Talking Heart (Boise, ID: Boise State University, 1987), 11-35, 40-43. And French-born Alice Guy Blaché was a secretary for Gaumont in France before moving to the US in 1907 and starting her own company, Solax, in 1910. Here she wrote, directed, and supervised productions. Women like Shipman and Guy Blaché found an early control in the industry because they could write, direct, and produce.

Influencing the Story

In addition to shaping the form of their craft, women influenced its content. Writing for the screen quickly emerged as a female art form, written by women for women. By 1910, 40% of the working class audience was female, according to Kathy Peiss, and company heads were well aware they had to meet the needs of this demographic.43Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure at the Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986), 148. To do so, they turned to the popular literary marketplace, and the romantic comedies, romantic dramas, and melodramas that had gained popularity among female readers in the previous century. These female-centered literary narratives were penned mostly by women and focused on women’s social concerns as girlfriends, wives, and mothers.44See Casella Kern, “Sentimental Short Fiction by Women Writers in Leslie’s Popular Monthly,” 113-22. Film companies hired women to write and adapt such stories for the screen. E. Ann Kaplan in “Mothering, Feminism and Representation: The Maternal in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film 1910-1940” identifies some of these films collectively as the “woman’s film.” Unlike the maternal melodrama which speaks to both the male and female spectator, she explains, “the woman’s film more specifically addresses the female spectator.”45E. Ann Kaplan, “Mothering, Feminism and Representation: The Maternal in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film 1910-1940,” in Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film, ed. Christine Gledhill (London: BFI Publishing, 1987), 124, 126. The common belief of the time was that women were uniquely suitable for writing the kinds of stories a female audience demanded. As Gary Carey explains in his study of Loos, women writers were seen as “more attuned than men to turning out the kitsch melodramas and hot-house romances that dominated the run-of-the mill Hollywood product of the period.”46Gary Carey, “Written on the Screen: Anita Loos,” Film Comment 6, no. 4 (Winter 1970-71): 51. Even women writers acknowledged their innate ability to deal with stories of love and marriage. In a 1918 Motion Picture World article, Beranger asserts that domestic stories, love triangles, and human interest narratives are “more ably handled by woman than men because of the thorough understanding our sex has of these matters.”47Clara Beranger, “Are Women the Better Script Writers?,” The Moving Picture World 37, no. 8 (24 August 1918): 1128. She also argues on the same page that there are more women than men writing in Hollywood. In a 1925 article in The Film Daily, Mathis declares that women know best the female mind and, as a result, “seem to succeed in the careful, fine detail work of scenario writing.”48Mathis, “The Feminine Mind in Picture Making,” The Film Daily XXXII, no. 58 (7 June 1925): 115. Among the women who delivered on these popular stories were Frederica Sagor who scripted romantic comedies, Mrs. Sidney Drew (Lucille McVey) who penned domestic comedies along with her husband, and Loos who was known for her slapstick comedies in the early years and romantic comedies throughout her career. Coffee, Julia Crawford Ivers, and Marion wrote the intensely emotional dramas and melodramas. There was no shortage of women writers in Hollywood willing to turn out the “writing to gender” studios demanded of them.

Lantern slide, The Marriage of William Ashe (1921), Ruth Ann Baldwin (w). Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery, W. Ward Marsh collection.

What women wrote, however, frequently straddled both Victorian and modern sensibilities. On the one hand, women in these films were stock characters, recognizable types: the virgin, the flapper, the working girl, the sacrificing wife/mother, the reformer, and the deceived/seduced woman. They were positioned in the social order as (potential) girlfriends, wives, and/or mothers who struggled to find and keep a man or to survive difficult domestic situations. Many, however, were also independent-minded women who negotiated for freedom inside of conventional relationships, sought unconventional relationships (across classes, for example), and tried to make the best of difficult relationships. Their stories showcase the tensions surrounding the gendered expectations of women in both the public and private sphere.49Interviews of and articles by women writers in the New York Times, Variety, Photoplay, The Moving Picture World, Motion Pictures News, Motion Picture Magazine, Picturegoer, Bioscope, and Skoll-Herald indicate that some women willingly turned out the “writing to gender” demanded of them, while others criticized the dominant ideology presented in such narratives. See Casella, “Feminism and the Female Author: The Not So Silent Career of the Woman Scenarist in Hollywood, 1896-1930,” The Quarterly Review of Film and Video 23 (2006): 222-32. These edgy women are found in such films as Beranger’s Miss Lulu Bett (1921), Ruth Ann Baldwin’s The Marriage of William Ashe (1921), Marion’s The Wind (1928), and Glyn’s It (1927). Berenger’s Lulu challenges the convention that women, unlike men, are solely defined by their marital status. Baldwin’s Lady Kitty publishes political satire and poses nude for a charity event. And Marion’s Letty struggles for dignity in an abusive relationship.50The multiple shooting scripts for The Wind indicate how Marion’s gritty tale of Letty’s defiance of an arranged and brutal marriage softened with each rewrite. See The Margaret Herrick Library, Turner/MGM Scripts, 3376-f.W-836-839 and 3377-f.W840-844. See also note 68. Glyn’s Betty Lou is a working girl and a flapper, wielding both social and sexual power. Higashi argues that the working woman status of the time shaped the female characters in these Cinderella-themed stories. Careers led to marriage even for those women not actively seeking a partner. Betty Lou, however, is also a flapper. As such, she represents what Higashi calls a new style of femininity: rebellious, sexually precocious, and capable of male friendships.51Higashi, 102-106. Refusing to wait for a man, Betty Lou openly initiates a romance with her boss. Complications ensue as a result of class differences and Betty Lou’s brazen personality, but the two eventually find common ground. While marriage is mentioned only briefly, this is the assumed next step in their relationship. The pull of marital expectations remained strong in these films, even for sexually-liberated flappers like Betty Lou.

Some women writers avoided stories of love and marriage by focusing on female characters who operate outside of the domestic sphere, though these stories frequently contained a romantic subplot. Grace Cunard and Gauntier created girl adventurers. Cunard, in collaboration with her husband Francis Ford, specialized in the female-lead adventure serials for Universal: Lucille Love, Girl of Mystery (1914) and The Broken Coin (1915). Gauntier’s action-packed stories feature spunky, athletic women engaging in death-defying exploits. Her Girl Spy (1908-1911) is based on the exploits of Belle Boyd, a Confederate spy in the Civil War. Francke argues that Gauntier’s choice of genre was an open challenge to the male action writer: “Gauntier had established that a woman writer was as adept with the thrills and spills of action-adventure genres as her male colleagues.”52Francke, 9. Gauntier does marry her girl spy off at the end of the series, but she admits in the November 1928 installment of “Blazing the Trail” that she did so because of the physical toll of doing her own stunts. In addition, her brains had been “sucked dry of any more adventures for the intrepid young woman.”53Gauntier, “Blazing the Trail,” Women’s Home Companion LV, no. 11 (November 1928): 170. Betty Burbridge, Carr, Baldwin, and Buffington also worked in another action arena: the western.54See Helen Colton, “Meet the Gals Who Write ’Em, Not Ride ’Em.” New York Times (31 October 1948): X5. Beranger took on the thriller in The Bedroom Window (1924) about a female mystery writer who brings her talents to a murder case. And Shipman’s women meet the challenges of wilderness life in such films as The Girl from God’s Country (1921) and The Grub-Stake (1923). According to Kay Armatage, Shipman’s heroine is a blend of vulnerable femininity and unbridled heroism which “allows her to resist conventional narrative inscriptions of the woman protagonist as victimized and rescued.”55Kay Armatage, The Girl from God’s Country: Nell Shipman and the Silent Cinema. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003), 31. Both films were the work of her newly-formed Nell Shipman Productions, which she moved to Idaho in part because of Hollywood’s continual challenge to the kinds of stories Shipman wanted to make.56Ibid., 118-119.

In addition, women tackled controversial social issues or broadened the narrative scope of their work to include a focus on male protagonists. Fairfax’s The Honor of His House (1918) and Macpherson’s The Godless Girl (1928) deal with alcoholism and juvenile delinquency respectively. Writer/director Weber devoted her career to making films that called attention to social problems. Where Are My Children? (1916) explores reproductive rights, while both Shoes (1916) and The Blot (1921) grapple with poverty and its impact on women. Dorothy Davenport Reid also focused on the social problem film, confronting drug addiction in Human Wreckage (1923) in which she also starred. As with some of her other films, however, writing credit remains uncertain. Among the writers who expanded the narrative focus of their films were Mathis, who adapted Frank Norris’ novel McTeague (Greed, 1924) about a dentist in the Midwest, and the epic Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925). Refusing to be labelled a woman’s writer, Dix regularly wrote films for male stars like her original The Call of the East (1917), starring popular Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa. Dix’s uncompromising approach to writing in Hollywood bears further study.

Jeanie Macpherson with Cecil B. DeMille and Paul Iribe on the set of Adam’s Rib (1923). Courtesy of Photofest.

Though some women may have challenged the “writing to gender” expected of them, they were still part of a collective codified in fan magazines as conventional working women. Authors were eager to assure readers that women could be “feminine” and still work in Hollywood. According to Photoplay’s “How Twelve Famous Women Scenario Writers Succeeded,” these were “normal, regular women…not short haired advanced feminists, not fadists.”57“How Twelve Famous Women Scenario Writers Succeeded,” 31. Speaking of Macpherson, Doris Delvigne writes in the 1920 Motion Picture Magazine that “There’s nothing masculine about this little French-Scotch girl who has interested the dramatic world with her craftsmanship. She’s not a blue-stocking with emancipated ideas, nor has her contact with the biggest men in the motion picture world given her that swaggering independence which is supposed to adhere to begoggled authors. She is the most utterly feminine thing you ever beheld.”58Doris Delvigne, “Mind the Little Things,” Motion Picture Magazine XIX, no. 6 (July 1920): 73. Of Unsell, M.H.C. writes, “She is so womanly–without the slightest trace of ‘pose’ or ‘literariness,’ and gives one a ‘homey’ feeling at once.”59M.H.C., 12. And Aline Carter in the 1921 Motion Picture Magazine praises Weber’s ability to produce, write, and edit without giving up a home life: “… she is the original woman who loves to linger over the table and ask for recipes.”60Aline Carter, “The Muse of the Reel,” Motion Picture Magazine XXI, no. 2 (March 1921): 62, 105. These popular magazines reminded the female audience that writing for the screen was women’s work.

In some cases, however, this ideologically-coded image contrasted sharply with the woman writer’s professional or personal life. According to Francke, Dix was a “self-confessed bluestocking”; she dressed informally on set and smoked with the crew.61Francke, 23-24. Her daughter’s biography notes that Dix openly refused female lead stories, disapproving of the Hollywood stereotypes of women and the fact that female-centered stories tended to deal with lighter topics.62Evelyn F. Scott, Hollywood. When Silents Were Golden (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972), 73. Levien’s biographer, Larry Ceplair, explains that before her film work she expressed radical political and social views, particularly as a writer for the Woman’s Journal, the voice of the suffragette movement. He acknowledges, however, that she had difficulty reconciling her film work with these radical views.63Larry Ceplair, “A Great Lady: A Life of the Screenwriter Sonya Levien,” in Filmmakers, No. 50, ed. Anthony Slide (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1966), viii, 15. Adela Rogers St. Johns, a Hollywood journalist, story consultant, screen writer, and author of source material, wrote about both conventional and unconventional women. Throughout her life St. Johns confronted gendered views of men and women, prompting sports journalist Mel Durslag to comment in her 1988 obituary that “She was a kind of wild, uninhibited woman before feminism came in.”64“Hearst Reporter Adela Rogers St. Johns Dies.” Obit. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (11 August 1988): 10. In silent era Hollywood women negotiated a fragile balance between their public and private lives.

Among the women who made films outside the Hollywood system were African-American filmmakers Tressie Souders, Eloyce King Patrick Gist, and Zora Neale Hurston. As noted earlier, careers for women in Hollywood were pretty much accessible only to white women, particularly middle class white women. There is no evidence, however, that Souders, Gist, or Hurston even desired to work in Hollywood. Very little is known about the making or distribution of director/writer Souders’ feature, A Woman’s Error (1922), which was produced by the Afro-American Film Exhibitors Company in Kansas City. More is known about Gist and Hurston who made films that furthered their political, religious, and/or social agendas. As Gloria J. Gibson writes in “Cinematic Foremothers: Zora Neale Hurston and Eloyce King Patrick Gist,” Hurston and Gist recognized the impact of the motion picture camera.65Gloria J. Gibson, “Cinematic Foremothers: Zora Neale Hurston and Eloyce King Patrick Gist,” in Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African-American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era, eds. Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 195. Gibson also notes that Gist and Hurston worked under the financial constraints of independent filmmaking, much like women of color today (195). Scholars also have mentioned journalist, historian, and musician Drusilla Dunjee Houston, though she was never actively involved in filmmaking. Houston wrote an anti-lynching screenplay, an answer to Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) that was never produced. Gist and husband James made highly moralistic, non-theatrical films that accompanied their religious services. Hell Bound Train (ca 1929-1930), which she retitled and orated, consists of a series of religious allegories, while the short Verdict Not Guilty (1930-1933) tells the story of a woman pleading for entrance to heaven despite her efforts to “prevent” motherhood, a reference to either birth control or abortion.66Ibid., 199-204. Similarly, African-American folklorist and novelist Hurston’s ethnographic films–Logging (1928), Children’s Games (1929), and Baptism (1929)–chronicle the daily life of southern black culture. Little is known of the purpose of Hurston’s filmmaking other than to present her research in a pictorial format. In fact, while black male filmmakers of the period have been the subject of extensive research, there has been very little scholarship on the work of black women filmmakers. Yet, as Gibson has argued, such women made their “mark with a camera.”67Ibid., 196.

The same could be said for those women working inside of the Hollywood system, but by the 1920s, a top-down model of studio production resulted in a series of ongoing problems, including both threats to creative autonomy and continuing struggles with low salaries. Marion and Pickford were frustrated particularly with the overly sentimental plots expected of them. According to Marion in Off With Their Heads: A Serio-Comic Tale of Hollywood, she and Pickford were fed up with Pickford’s “eternal child” character and the endless happy endings studios demanded. She and Lillian Gish experienced similar constraints while working on The Wind. When told she had to soften the ending of the film, Marion and some of the crew “created our own storm, to no avail.”68Marion, Off With Their Heads: A Serio-Comic Tale of Hollywood (New York: Macmillan, 1972), 64, 67, 160. Also troublesome was the increasingly complex assembly line of production that resulted in a shooting script that bore little resemblance to the original scenario. Though promised pre-production control, Glyn found it difficult to shepherd her work through with minimal interference. Like many literary writers in Hollywood in the 1920s, her work was severely altered. According to her son’s biography, “It was their names and not their literary abilities which were required by the studios.”69Glyn, 275. In a 1923 New York Times interview entitled “Scenario Writers Must Find Theme,” Mathis notes that when she first started out, she had to fight for her ideas. Though she gradually gained control of the production process, she still faced opposition: “… if a director does not want to make a production in a particular way, he needs a healthy guard to force him.”70“Scenario Writers Must Find Theme,” New York Times (15 April 1923): X3. In addition to struggles with creative autonomy, writers in the growing story departments also grappled with low salaries. Though top writers like Marion, Loos, and Macpherson eventually commanded good salaries, the profession as a whole did not. Marion admits in Off With Their Heads, that “scenario writers were pushed into the background, poorly paid, their talent unexploited.”71Marion, Off With Their Heads, 17. Coffee was particularly outspoken on the issue of equitable pay and suffered the consequences. In the 1920s, Louis B. Mayer fired her for demanding too much money, rehiring Coffee five years later. In the interim she found work with DeMille.72See Thomas Slater, “Lenore J. Coffee,” in American Screenwriters, Second Series, ed. Randall Clark (Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1986), 93. The career woman in Hollywood was experiencing the growing pains of a changing industry.

In addition, crediting problems continued well into the 1920s, even though freelance submissions, rarely credited in the early days, had fallen.73Staiger notes the disappearance of freelance submissions in “Blueprints for Feature Films,” 190. When multiple writers in the newly-formed story departments worked on the scenario and the final shooting script, crediting frequently acknowledged only one author, and not always the major contributor. Sometimes the last person who had a hand in the script, even only minimally, was the one receiving screen credit. Often writers who rescued weak scenarios, did not get acknowledged at all. Coffee, known as the fixer-upper for saving troubled productions through rewrites and titling, admits in an interview with Patrick McGilligan that she did not always get credit for such work. She recalls one time in the early days of sound when she had written additional dialogue on a film. Another writer phoned her and wanted her to give up the credit. She told him “I’ve heard the age of chivalry is gone, and now I believe it.”74Patrick McGilligan, “Lenore Coffee: Easy Smiler, Easy Weeper,” in Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood’s Golden Age, ed. Patrick McGilligan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 142-43. Coffee then hung up the phone. Sometimes adapters, particularly early and lesser-known writers, found their screen credit eclipsed by the author of the original works. They also were forgotten in film reviews, again in favor of the author of the original work. Even Fairfax, well-known in the business by the 1920s, experienced this problem. In 1926 she wrote and produced The Blonde Saint, from a Stephen French Whitman novel. However the only writing credit listed on the BFI copy is Whitman’s. Reviews in Bioscope and the New York Times also ignore her authorship in favor of Whitman’s.75“The Blonde Saint.” Bioscope 70, no. 1066 (17 March 1927): 55-56; and Mordaunt Hall, “The Screen,” New York Times (23 November 1926): 27. Staiger believes that the “division of labor” resulting from the growing corporatization of the industry accounted for this threat to authorship.76Staiger, “Dividing Labor,” 21-23.

Women, particularly those who had long careers in the industry, handled these problems with autonomy and authorship in a number of ways. They formed writer/director and writer/writer partnerships. They also became writing department and company heads, joined or formed independent units or companies, held multiple positions as writers, directors, and producers, and organized writing guilds. Marion quickly discovered that the only way to maintain complete control over her script was to be the writer and director.77See De Witt Bodeen, “Frances Marion: Part II, She Wrote the Scripts of Some of the Milestone Movies,” Films in Review XX, no. 3 (March 1969): 139. The next best thing was to be part of writer/director partnerships. These included Loos and Emerson (co-writer), Meredyth and Wilfred Lucas (co-writer), and Macpherson and DeMille.78When she was a script supervisor, Macpherson worked closely with DeMille to guarantee her work was filmed as written. Francke believes that DeMille’s output was far more varied due to his collaboration with Macpherson (16).Among the husband and wife writing partnerships, in addition to Loos and Emerson, were Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew. Early teams included Anne and Bannister Merwin at Edison and Maria A. Wing and William E. Wing at Biograph and Selig, though little is known about Anne and Maria’s contributions.79See Edward Azlant, “Screenwriting for the Early Silent Film: Forgotten Pioneers, 1897-1911.” Film History 9, no.3 (September 1997): 243-44. Some writers were also scenario editors: Breuil and Bertsch at Vitagraph, Carr at North American, and Baker at Bosworth.80See Azlant, 241. Writer/actor teams also were common with women film writers pairing with women actors. Marion wrote regularly for Pickford, Clara Kimball Young, Constance and Norma Talmadge, and Marie Dressler (Bodeen, “Frances Marion Wrote the Scripts of Some of the Milestone Movies,” Films in Review XX, no. 2 [February 1969]: 80-81, 87). Both Marion and Fairfax formed their own companies: Frances Marion Pictures and Marion Fairfax Productions. Gauntier held multiple positions at Kalem–writer, actor, producer, director, critic, scenario editor, and studio manager–and founded her own company Gene Gauntier Feature Players with Sydney Olcott.81Researchers continue to struggle with determining Gauntier’s authorship, since existing screen credit does not reflect the extent of her contribution. In “Blazing the Trail,” which covers her Kalem years, Gauntier notes writing, producing, and directing activities, but does not address the frequent absence of screen credit (October 1928, 183-184; November 1928:166, 168-170; LV, no. 12 [December 1928]: 132, 134; and LVI, no. 3 [March 1929]: 19). The final installment of “Blazing the Trail” in March, does mention one disagreement with Kalem over crediting: “Now we learned among other disconcerting facts that From the Manger to the Cross was to be distributed without our names. The Kalem Company alone would profit by our own work” (146). A few paragraphs later, she alludes to possible career problems, but provides no detail: “So our family of pathfinders disbanded, as pioneers do when the long trail is ended, and each one departed into a new environment to build for himself. As settlers in a new land, some were submerged while others rode blithely on the top crest of popularity” (146). Correspondence five years earlier with Photoplay author Frederick James Smith, however, suggests the breadth of her work: “In addition to playing the principal parts, I also wrote, with the exception of a bare half-dozen, every one of the five hundred or so pictures in which I appeared. I picked locations, supervised sets, passed on tests, co-directed with Sidney Olcott, cut and edited” (“Unwept, Unhonored and Unfilmed,” Photoplay XXVI, no. 2 [July 1924]: 67, 101). See also Gaines, “Pink-Slipped: What Happened to the Women in the Silent Film Industry,” in The Wiley-Blackwell History of Film. Volume 1. Origins to 1928, eds. Cynthia Lucia, Roy Grundmann, and Art Simon (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2012), 157. This situation never seemed to bother Gauntier as she was involved in multiple aspects of a production and did receive credit for her acting. Gauntier saw filmmaking as an ensemble endeavor. However, the tone of the March installment of “Blazing the Trail” suggests that even this ensemble contribution was getting lost in industry expansion. Lillian Case Russell started a film company with her husband. And Mathis headed the script unit at Metro; she also was a producer at Goldwyn and First National. The collaborative, egalitarian nature of their work and their presence in the upper echelons meant they had a hand in the final product. In addition, women were tackling inequities as active members of societies and leagues launched to protect authorship and autonomy. Baker and Weber were among the founding members of the Photoplay Authors’ League, according to the Mariposa Gazette in 1914.82“Photoplay Authors’ League Organized,” Mariposa Gazette 1 (30 May 1914): 3. http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=MG19140530.2.51. Pierce sought the assistance of both the Photoplay Authors’ League and the National League of Pen Women when she was denied screen credit for adapting Judith of Bethulia. See Sargent, “The Photoplaywright,” The Moving Picture World 20, no. 8 (23 May 1914): 1109. Finally, women’s friendships helped them navigate a continually changing industry. According to Marsha McCreadie in The Women Who Write the Movies (1994), “there seems to have been an informal but strong and highly effect networking system among women.”83Marsha McCreadie, The Women Who Write the Movies. (New York: Burch Lane Press, 1994), 6. Marion confirms this in an interview with De Witt Bodeen. St. Johns helped her secure the meeting with Weber that launched her career.84Bodeen, “Frances Marion Wrote the Scripts,” 75. See also Bodeen, “Frances Marion: Part II,” 139, 142. By the end of the silent period, women were hiring each other and teaching newcomers the business.

The women writer’s dominance in the industry, however, virtually disappeared with the coming of sound. The industry that afforded them jobs and sometimes lucrative careers had altered drastically. Maher argues that the transformation of Hollywood into a business with both a national and international market and a centralized producer system pushed women from positions of power and left little room for both the independent and collaborative working culture women were used to. She notes, however, that such changes affected predominantly producers, directors, and editors, as women screen writers continued working into sound.85Maher, 134, 157, 203. Gaines in “Pink-Slipped: What Happened to the Women in the Silent Film Industry” notes that women filmmakers did not totally disappear with the coming of sound. She recommends that scholars “move from the narrative of ‘no woman in 1925’ to the narrative of the ascendance for some that was ‘over by 1925’” (164). Some women writers, like Akins, Buffington, Burbridge, Coffee, Dix, Lillie Hayward, Adelaide Heilbron, Levien, Loos, Lovett, Marion, Meredyth, Murfin, Marion Orth, and St. Johns, did make the transition into sound, but they faced a severely altered professional environment. Marion quickly learned that writers now were “like Penelope–knitting their stories all day just to have somebody else unravel their work by night.”86Bodeen, “Frances Marion: Part II,” 139. In a 1939 letter to Alice Kauser, Akins expresses her frustration with the movie business, noting that writing what one chooses had become “a rare privilege.”87Zoë Akins to Alice Kauser, 20 October 1939, Zoë Akins Papers, ZA 1898, Box 79, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. See also Alan Kreizenbeck, Zoë Akins: Broadway Playwright (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 149, 208. Those writing from home found their services were no longer wanted as both story ideas and scenarios now emerged from story departments. Drew and Williams, who made names for themselves in serials, discovered the form no longer desirable. Though long out of the business by the coming of sound, Gauntier noted in a 1924 letter to Photoplay that changes in the industry had made it impossible for her to continue working. Speaking of her final years in the business after her company folded in 1914, she writes, “Conditions had changed so. I went with Universal for a short time, when the new plant, Universal City, was opened. After being master of all I surveyed, I could not work under the new conditions.”88Smith, 102. Once a dominating force in the industry, women writers had become workers in a well-oiled machine. They were quickly fading from the public limelight.

Women who wrote for the screen in the silent era, however, did leave their mark. They were a significant part of concretizing the language of their craft. They legitimized writing for the screen as a new medium at a time when screen writing was not a discipline and only beginning to be a business. And they offered constructive views on the art of photoplay writing. However, due to the assembly line of production, the absence of pre-production shooting scripts in the early days, and the lack of systematic crediting throughout the period, the extent and nature of women’s contribution in all areas of writing continue to be important subjects for researchers. There is still much work to be done on how women distinguished themselves as writers, sometimes resisting the formulaic Hollywood model of storytelling. Studies also need to explore how they struggled to establish authorship in the wake of industry changes, and how and why some women writers adjusted to these changes. The role of the independent filmmaker/writer, like Fairfax, Hurston, and Gist bears further study. Finally, scholarship needs to interrogate the intersection of social and economic factors that contributed to the woman writer’s eventual loss of power in an industry they helped forge.

See also:Hetty Gray Baker, Ruth Ann Baldwin, Clara Beranger, Ouida Bergère, Marguerite Bertsch, Alice Guy Blaché, Beta Breuil, Adele S. Buffington, Lenore Coffee, Sada Cowan, Beulah Marie Dix, Mrs. Sidney Drew, Marian Fairfax, Gene Gauntier, Lillian Gish Eloyce King Patrick Gist, Elinor Glyn, Katharine Hilliker, Zora Neale Hurston, Julia Crawford Ivers, Maibel Heikes Justice, Sonya Levien, Anita Loos, Jeanie Macpherson, Francis Marion, June Mathis, Bess Meredyth, Lorna Moon, Jane Murfin, Mary Pickford, Olga Printzlau, Dorothy Davenport Reid, Lillian Case Russell, Frederica Sagor, Nell Shipman, Tressie Souders, Adela Rogers St. Johns, Margaret Turnbull, Eve Unsell, Kathlyn Williams, Dorothy Yost.