In 1920, Leila Lewis gave a lecture to the Women’s Freedom League, a UK organization that campaigned for suffrage and sexual equality. The subject of her talk was “Opportunities for Women in the Film Business.” Although not yet thirty, Lewis was already an established film publicist and the object of her talk was to promote the wide range of film industry jobs that were open to women. A June 17, 1920 article in Kinematograph Weekly reported that Lewis had questioned the “monopoly held by men in so many jobs in the film industry,” arguing that “it ought not to be a question of sex when anybody was selected for work, but a question of ability to do the work” (135). Attempting to dispel the widely held notion that the only opportunities for women were in front of the camera, Lewis outlined a range of potential roles, including producer (meaning director), scenario writer, art director, casting director, censor, wardrobe and make-up, and working on “the business side” (135). Interestingly, she made no mention of her own professions of publicity and journalism, despite these being two areas in which women had already begun to distinguish themselves.

Leila Stewart photographed by her husband, Alex ‘Sasha’ Stewart, 1925. Courtesy of the Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Lewis had entered the film business via editorial and advertising work and, according to an October 12, 1939 article in Kinematograph Weekly, was at one point the only woman to run her own Fleet Street advertising agency (5). Her first film job was with the rental company Bolton’s Mutual Films where she attracted attention with her series of articles, “Mutual Interests,” which ran from February to June 1917 in the trade paper The Bioscope. While musing on a range of issues regarding cinema and its role in modern life (education, escapism), Lewis’ pieces also served as persuasive “advertorials” for the latest Bolton’s releases. From Bolton’s, Lewis moved to the Stoll Picture Theatre, Kingsway, one of central London’s grandest cinemas. Establishing a reputation as an imaginative and innovative publicist, Lewis set up a magazine for the cinema called the Kingsway Gossip and, in 1918, created the Stoll Picture Theatre Club, which offered its members cinema season tickets and also hosted talks, events, and tours of British studios. Lewis’ work grabbed the attention of the film trade press, who noted in a May 2, 1918 article in Kinematograph Weekly that “the theatre owes not a little of its success to its capable press lady” (51).

Lewis was an active figure in the industry. As well as giving talks and contributing articles to the trade papers, she also sat on the committee of the Film Press Club, which was, as The Bioscope reported on June 3, 1920, formed for those working in film publicity, advertising, and journalism (5). She was keen to develop the style and reach of film publicity and worked constantly to engage the popular—as opposed to trade—press in the business of reviewing and promoting films. In her “Opportunities for Women” talk, Lewis suggested that women were “born wheedlers” (135) and this comes across in an article she wrote for The Bioscope in December 1928, which asserted that a good publicist needed to present film stories as “news”:

If film publicity is presented to them [newspaper editors] as news, they welcome it, but they will not put in a bald announcement giving the name of the film, the name of the star, the theatre at which it is being shown […] the usual material, which, they feel, ought to be paid for as an advertisement. […] They must have a large quantity of jam in the shape of interesting material in which to swallow their pill–advertising a theatre for nothing in their editorial columns (223).

After leaving the Stoll Picture Theatre, Lewis set herself up as a publicity consultant and also had a stint as a film critic, writing for the magazines Tit-Bits and Daily Graphic, according to Kinematograph Weekly (1926, 42) and Stoll’s Editorial News (1920, 4). She also undertook freelance work for British producer George Clark and was briefly at British & Colonial, as noted later by Kinematograph Weekly (1939, 5). In 1921, she joined Allied Artists, the British distribution arm for United Artists, as Publicity Director, beating, as The Bioscope pointed out, several prominent publicity men to the job (1921, 12). Lewis ran the campaign for Allied’s first UK release, the Mary Pickford vehicle Pollyanna (1920), but does not appear to have stayed with Allied Artists for long after this.

From around 1923 until 1926 she was head of publicity at the distributor W&F. While there, she worked on the promotion of Harold Lloyd releases as well as British productions made by Gainsborough. In 1926, she joined Warner Brothers as Publicity Manager and was responsible for promoting the Vitaphone sound system. Lewis claimed in The Bioscope in December 1928 that “I am so sold on the value of adding sound to the silent screen, that I have found it an easy matter to talk and write all day, every day and almost every night about Vitaphone” (223).

It was around this time that Lewis began working under her married name of Stewart, although she had been married to the photographer Alexander Stewart (professionally known as Sasha) since 1919. In the 1920s, Sasha established himself as portrait photographer and became well known for his photographs of society, theater, and film figures. Their two professions no doubt supported each other, and Lewis almost certainly secured commissions for her husband, especially in the early 1930s when he set up as a film publicity stills photographer. Together, they were a talented and well-connected couple, and Sasha’s studio “day books” contain a number of references to Leila and to attending various society and film-related events. Sasha also took several portraits of his wife, many of which are held in Sasha’s archive in the Hulton Archive, now owned by Getty Images.

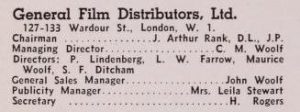

Lewis was clearly a skilled and hard-working networker, communicator, and persuader, and had a natural inclination to use her connections to help people. Director Adrian Brunel recalls Lewis inviting him to her and Sasha’s Bloomsbury flat for dinner “in order to meet Michael Balcon and his lovely wife Aileen. Mick Balcon was a coming producer and Leila, who was always plotting to help people, thought that we might be useful to each other” (1949, 108). Tough and respected, Lewis also inspired affection. Annual editions of the Kine Yearbook show that in the 1930s Leila worked for a time as a casting director at Gaumont-British (1933, 271) before returning to publicity, first as Publicity Manager at Gaumont-British distributors (1936, 291) and then, in the same role, at General Film Distributors (1937, 298). She remained at GFD until her early death, at the age of forty-six, in October 1939. An obituary in Kinematograph Weekly lamented the loss of “a great publicity chief, the acknowledged head of her profession” (1939, 5). Today’s Cinema described her as “one of the most hard-working and conscientious executives in the trade” and felt that “the effect of her work will live as a monument to carefully conceived, expertly planned and successfully launched publicity” (1939, 2).

See also: Mabel Condon, Beulah Livingstone