by

Annette Förster

If we merely looked at contemporary advertisements and reviews, it would appear that Musidora had directed only two films in the silent era: Vicenta (1919), and La terre des taureaux/The Land of the Bulls (1924). These credits can be further substantiated by personal statements about the making of these films published by Musidora herself in contemporary periodicals. There, she additionally claimed credit for writing both scripts as well as for editing La terre des taureaux. However, on the two other films that were produced under the banner of her company, Société des Films Musidora, she credited as director her codirector Jacques Lasseyne. Even the richly illustrated publicity booklets of Pour Don Carlos/For Don Carlos (1921) and Soleil et ombre/Sun and Shadow (1922) listed Musidora only in the cast, and her article in the magazine Ève bore the telling title “Comment j’ai tourné ‘Don Carlos’” or “How I Acted in Don Carlos” (10). After the 1940s, however, Musidora began to claim the codirector and adaptation credits of these productions for herself, and these credits have now been accepted as definitive. Additionally, she added the credit for codirection, with Roger Lion, for La flamme cachée/The hidden flame (1918), which she mentioned in a 1950 article on her professional collaboration with her artistic mentor and longtime friend, Colette.

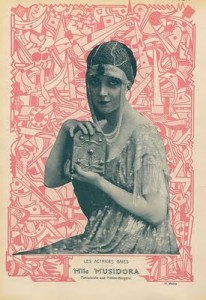

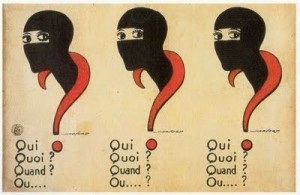

Musidora (a/d/p/w) in the magazine Fantasio (c. 1912). Courtesy of Beth Ann Gallagher’s Flickr account.

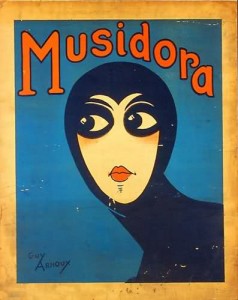

Poster by Guy Arnoux for Les Vampires (1916); Musidora as Irma Vep.

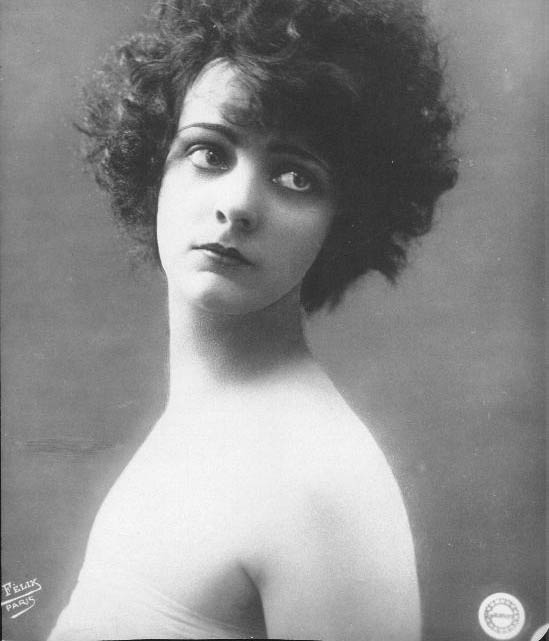

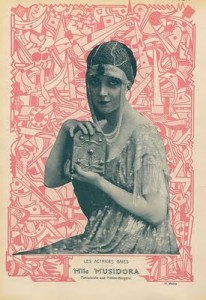

Musidora. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française.

At the time that Musidora began making motion pictures, she was an acclaimed film and revue actress. She performed in the most popular revues at French music halls and cabarets, such as the Folies Bergère, Concert Mayol, and La Cigale. In cinema, she had cheered up the public during the dark years of the Great War in some fourteen comedies and in her roles of the female gangsters Irma Vep and Diana Monti in the Gaumont crime series Les vampires (1915–1916) and Judex (1916), directed by Louis Feuillade. Musidora’s reluctance to claim the screenwriting and directorial credits on her own productions may therefore be partly explained by her status as a film star and a revue celebrity. From the point of view of publicity, her fame as an actress was a bigger asset than her name as a director or a producer. Since she played the leading parts in all of the productions of her own company, this does not, however, explain her inconsistency. Another explanation for Musidora’s withholding of her own contribution is that she strategically foregrounded the names of literary authors. What the three films in which Musidora did not credit herself as codirector have in common is that they were adaptations of the work of best-selling literary authors: La flamme cachée was written by Colette, Pour Don Carlos by Pierre Benoît, and Soleil et ombre by Maria Star. Granting more prominence to these authors than to herself may have been a publicity strategy rather than intentional self-effacement.

One question prompted by the surviving prints of Musidora’s productions concerns the differences between them in terms of style. The historical adventure story Pour Don Carlos and the tragic romance Soleil et ombre were set in the Basque Pyrenees and in the Spanish province of Andalusia. Both can today be seen as stylistically ambitious productions that call to mind aesthetic ideals then current in French film production. A widely shared ideal was shooting on location and taking advantage of the evocative qualities of provincial sites. In Musidora’s films, shots of landscapes, sites, and objects convey atmosphere and mood. Like theatre and film director André Antoine, she preferred to adapt gripping stories and to employ a mix of stage and lay actors. Colette, in her film reviews, promoted the use of accurate costumes and props as well as “photogenic” acting (Virmaux 1980, 67–75). This entailed an impassive acting style and an effacement of the act of acting that resulted in expressing as little as possible and yet evoking a range of emotions. In order to demonstrate that she was capable of such acting, Musidora as the screenwriter altered the ending of Benoît’s novel from an escape scene to a burial scene meant to rival the highly acclaimed dying scene played by Marie-Louise Iribe in Jacques Feyder’s L’Atlantide (1921). The burial scene had been difficult to play, Musidora asserted in a letter to the novelist: “I wanted my face to be covered like my body, so that the impression of getting buried would be genuine. I took another deep breath, and searched for total immobility. And I gave the sign: ‘Action…. ’ The first scoop of ground fell on my chin and cheeks… The second covered my eyes. The third left only the tip of my nose free. The ultimate, heavy one, hid my face completely. It was about time! All of this lasted barely twenty-five seconds, but I suffocated; my mouth ate crunching earth, my ears were stuffed with humid earth, I kept my eyelashes closed, fearing to fill my eyes with scratching grains of sand. And it was with the word ‘Damn!… ’ that I regained my friends, the air, the sun, warmth and life.” (as cited in Cazals 1978, 79–80). This lengthy quote offers us Musidora as the leading actress and the director at once.

Screenshot, Musidora in Les Vampires (1916).

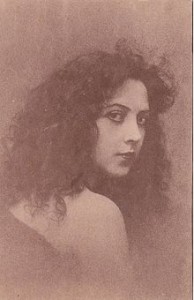

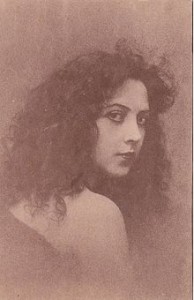

Musidora portrait. Private Collection.

While her films were favorably reviewed in the press, Musidora as producer reputedly only lost money on them. It remains unclear whether this was due to the terms of her contract, as she claimed in a 1946 interview with Renee Sylvaire, or to the fact that the films failed at the box office. Although her fourth production, La terre des taureaux,like Soleil et ombre, was set and shot in Andalusia, Musidora now refrained from dramatic storytelling and photogenic acting. Instead, she returned to the comic and playful genres that had brought her gratification as an actress and included ironic comments on her cinema career. A scenario held at the Bibliothèque du Film actually implies that the production was conceived as a combined film and theatre show, with Musidora and her partner, the Cordoban mounted bullfighter Antonio Cañero, acting additional scenes live on stage (Musidora Collection, Musidora 3–B1). The filmed parts as well as the stage scenes can be read as Musidora’s response to a film world and a press that wished to see her in dramatic parts and in an acting style, that, in her experience, curtailed her capabilities. It may then be considered a sign of professionalism that Musidora the film director quit the silent cinema with self-irony and humor. Except for one supporting part in another film, she left for the popular stage, which she never had actually abandoned.

Poster for Les Vampires (1916); Musidora as Irma Vep.

Bibliography

Cazals, Patrick. Musidora. La dixième muse. Paris: Éditions Henry Veryier, 1978.

Förster, Annette. Histories of Fame and Failure. Adriënne Solser, Musidora, Nell Shipman: Women Acting and Directing in the Silent Cinema in The Netherlands, France and North America. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Utrecht: Univ, 2005. 141-289.

------. Women in the Silent Cinema: Histories of Fame and Fate. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Lacassin, Francis. “Musidora Filmography." In Patrick Cazals, Musidora, La dixième muse. Paris: Éditions Henry Veryier, 1978. 213-223.

Musidora, “Colette et le Cinéma Muet.” In Patrick Cazals, Musidora. La dixième muse. Paris: Éditions Henry Veryier, 1978. 195-199.

------.“Comment j’ai tourné Don Carlos.” Ève (30 January 1921): 10.

------. “Grandes Enquètes d’Ève: Comment je suis devenue Torera.” Ève (28 September 1924): 11-18.

------. Interview with Renée Sylvaire. Manuscript. Committee on Historical Research Collection [Fonds Commission des Recherches Historiques], CHR29-B1. Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française.

------.“La Vie d’une vamp”, Ciné-Mondial 42-48 (12 June – 17 July 1942): n.p.

------. Paroxysmes. De l’amour à la mort. Paris: Éditions Eugène Figuière 1934.

------. Souvenirs sur Pierre Louÿs. Muizon: Éditions “À L’écart,” 1984.

------. “Vicenta.” Comoedia illustré (15 February 1920): 207-208.

Virmaux, Alain and Odette, eds. Colette at the Movies. Criticism and Screenplays. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1980, 67-75

Archival Paper Collections:

Collection Johan Daisne [Fonds Johan Daisne]. Folder Musidora [Dossier Musidora]. University of Ghent.

Committee on Historical Research Collection [Fonds Commission des Recherches Historiques]. Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française.

Musidora Collection [Fonds Musidora]. Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française.

Publicity folder Pour Don Carlos (4e RK 7565), “Musidora,” Biographie-Critique (4e RT 9736), “Musidora” Iconographie Personalités (4e Ico Per). Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française.

Filmography

A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles:

1. Musidora as Producer, Co-Director or Director, Screenwriter, Actress

Vicenta. Dir., sc., prod., ed.: Musidora (Société des Films Musidora 1919) cas.: Musidora, Jean Guitry, Guiraud-Rivière, Lancien, deGoncin, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Cinémathèque Française [incomplete, only a 19-minute fragment survives].

Pour Don Carlos. Dir.: Musidora, Jacques Lasseyne, sc./adapt.: Musidora, after the novel Don Carlos by Pierre Benoît, ph.: Frank Daniau-Johnston, Crouan (Société des Films Musidora 1921) cas.: Musidora, Abel Tarride, Jean Signoret, Jean Guitry, Simone Cynthia, si., b&w and tinted, 35mm., 4754 of 7874 ft. Archive (most complete): Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Cinémathèque Française.

Soleil et ombre/Sol y sombra. Dir.: Musidora, Jacques Lasseyne, sc./adapt.: Musidora, after the story L’Espagnole by Maria Star, ph: Frank Daniau-Johnston, ed.: Nini Bonnefoy (Société des Films Musidora 1922) cas.: Musidora, Antonio Cañero, Paul Vermoyal, Simone Cynthia, si., b&w, 2227 of 4347 ft. Archive: Cinémathèque Française, Filmoteca Española.

La terre des taureaux/La tierra de los toros. Dir., sc., prod., ed.: Musidora, ph.: George Guérin. (Société des Films Musidora 1924) cas: Musidora, Antonio Cañero, si. with live performance, b&w, 3982 ft. Archive: Cinémathèque de Toulouse, Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Library of Congress.

2. Musidora as Actress

Severo Torelli. Dir./sc. Louis Feuillade, after the epic poem by François Coppée, (Gaumont 1914), cas.: Musidora, Renée Carl, Fernand Hermann. si., tinted, 35mm, 3366 of 3963 ft. Archive: Cinémathèque Française.

Les vampires. Dir/sc.: Louis Feuillade, ph.: Georges Guérin (Gaumont 1915/1916) cas.: Musidora, Renée Carl, Marcel Lévesque, Édouard Mathé. si., tinted, 35mm, 10 installments, 26.932 ft. Archive: Cinémathèque Française, Library of Congress.

Lagourdette Gentleman Cambrioleur. Dir/sc.: Louis Feuillade, (Gaumont 1916) cas.: Musidora, Marcel Lévesque, si., b&w, 35mm, 1535 of 1903 ft. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Le pied qui étreint. Dir./sc. Jacques Feyder (Gaumont 1916) cas.: Musidora, Marcel Levesque, Biscot, si., b&w, 35mm, 1433 ft. Archive: Cinémathèque Française.

Judex. Dir./sc.: Louis Feuillade, ph.: Georges Guérin (Gaumont 1916) cas.: Musidora, Yvette Andreyor, Marcel Lévesque, René Cresté, si., tinted, 35mm, 12 installments, 26.593 ft. Archive: Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée [FRB], Cinémathèque Française, Svenska Filminstitutet , BFI National Archive, Cineteca Nazionale, Národní Filmov Archiv, George Eastman Museum, Lobster Films, Library of Congress.

Le reveil de l’artiste. (First tableau of C’est pour les orphelins!) Dir. Louis Feuillade, sc. Roger Lion (Gaumont 1917) cas.: Musidora, Yvette Andreyor, Marcel Lévesque, Bout de Zan, si., b&w, 35mm, 262 ft. Archive: Lobster Films.

B. Filmography: Non-Extant Film Titles:

1. Musidora as Co-Producer, Co-Director, Screenwriter, Actress

La flamme cachée, 1918; La Magique image, 1950.

2. Musidora as Actress

Le calvaire, 1914; Tu n’épouseras jamais un avocat, 1914; Bout de Zan et l’espion, 1915; Bout de Zan et le poilu, 1915; Le Colonel Bontemps, 1915; Celui qui reste, 1915 ; Le Collier de perles, 1915; Le Coup du fakir, 1915; Deux Françaises, 1915; L’Escapade de Filoche, 1915; Le Fer à cheval, 1915; Fifi Tambour, 1915; Jeunes filles d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, 1915; Les Noces d’argent, 1915; Le Roman de la Midinette, 1915; Le Sosie, 1915; Triple Éntente, 1915; L’union sacrée, 1915; Les Fourberies de Penguin, 1916; Les Finançailles d’Agenor, 1916; Les Mariés d’un jour, 1916; La Peine du talion, 1916; Le Poète et sa folle amante, 1916; Si vous me n’aimez pas, 1916; Débrouille-toi, 1917; Mon oncle, 1917; La Vagabonde, 1918.

C. DVD Sources:

Les Vampires. DVD. (Kino US 2012)

Judex. DVD. (Flicker Alley US 2004)

D. Streamed Media:

Les Vampires (1915-16) is streaming online via Kanopy

Judex (1916) is streaming online via Kanopy

Research Update

January 2023: A fragment of Vicenta, which was previously listed as lost in this filmography, was discovered in 2016 at the Cinémathèque française.

New publication: Musidora qui êtes-vous? Edited by Carole Aurouet, Marie-Claude Cherqui, and Laurent Véray (Paris: Editions de Grenelle, 2022).

Citation

Förster, Annette. "Musidora." In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. <https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-f4nt-4j92>