Natalia Bakhareva was the first self-sufficient female film producer in Russia. Unlike Antonina Khanzhonkova and Elizaveta Thiemann, who produced films for studios officially owned by their husbands, Bakhareva opened her own film company and became its official head. In the 1916 reference guide Vsia Kinematographia/All the Cinematography, there are two titles for her company: “The Artistic Film” [“Khudozhestvennaia lenta”] and “N. D. Bakhareva and K” (31). In the trade press, Bakhareva’s studio was later called “The Russian Film Business” [“Rossiiskoe Kino-delo”] and “The Film Business” [“Kino-delo”] (“Novye lenty” [1917]; “Khronika” [1916]). Sometimes films produced by her studio were associated with a company called Prodalent, which distributed them.

In her studio, Bakhareva worked not only as a producer but also as a screenwriter. She wrote scripts for six films, but none of her screenplays have been preserved. Moreover, all the films released by The Artistic Film (and later The Russian Film Business) are lost, and it is hard to judge their aesthetic value. We are fortunate to have Bakhareva’s memoirs today, which are held at the Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European Culture at Columbia University, but these papers are dedicated to the writer Nikolai Leskov, Bakhareva’s famous grandfather, and, unfortunately, provide very little information about her work in cinema and the films she made.

In fact, Bakhareva’s grandfather was a presence throughout much of her career. When the news about The Artistic Film first appeared in the trade press in 1915, journalists emphasized that the new company was founded by Leskov’s granddaughter (“Khronika” [1915]). Some readers could guess that “Bakhareva” was a pseudonym borrowed from Leskov’s novel No Way Out (1864); her real name was Natalia Dmitrievna Noga.

Bakhareva was the daughter of Leskov’s daughter Vera and Ukrainian landowner Dmitrii Noga. In her unpublished memoirs, she puts 1887 as her date of birth, but the evidence and documents collected by Andrei Leskov, who has written the fundamental book Nikolai Leskov’s Life, suggest that she was born earlier, between 1880 and 1885 (Leskov 109-130). She spent her childhood at her father’s estate named Burty. As Bakhareva recalls in her memoirs, in the mid-1890s, the family grew poor, sold the estate, and, soon after that, her parents separated. Natalia and her mother moved to Kyiv (Bakhareva 11). There, Natalia was a student at the Fundukleev gymnasium, the first and one of the most famous girl’s grammar schools in Russia, and then studied acting at the Kyiv drama school (I.T.).

In 1904, Natalia and her mother moved to St. Petersburg, and the family faced new financial problems. In her memoirs, Bakhareva mentions that she had to work for the Ministry of Public Instruction for five years (Bakhareva 12). However, she also continued with her theatrical career. In a letter to the famous publisher Alexei Suvorin, she wrote that she had been accepted to the troupe of the People’s House theatre [Narodnyi Dom] (Noga). It has also been reported that she acted in Lydia Yavorskaia’s New Theater [Novyi teatr] during this period (I.T.). In 1909, Bakhareva made her debut as playwright, adapting her grandfather’s story Skomorokh Pamphalon/Buffoon Pamphalon for the stage. The State Theater Library of St. Petersburg holds six plays written by Bakhareva between 1909 and 1917.

In the late 1900s, Bakhareva also became a journalist when the influential critic Aleksandr Izmailov got her a job at Peterburgskii listok, one of the major Russian newspapers (Leskov 129). She was the head of the theater department and acted as the newspaper correspondent in Europe: Bakhareva represented Peterburgskii listok in Venice when Countess Maria Tarnovksaia was involved in a scandalous murder trial (Orem 2-3). Due to her work in the theater and newspaper industries, Bakhareva gained many connections, which probably helped her as she set up her film business. In her memoirs, she does not mention why she turned from theater to cinema, but she likely considered the film business, which was still new in Russia, an easier and faster route to success.

In the trade press, the foundation of Bakahreva’s studio The Artistic Film was reported in June 1915 (“Khronika” [1915]), but the company’s first films were released earlier; Bakhareva recalls in her memoirs that she started the business in 1914 when she left Peterburgskii listok (Bakhareva 12). The chief film director of the new studio was Aleksander Panteleev who had worked in cinema since 1909. Bakhareva was fortunate to hire such an experienced film director as very few of them lived in St. Petersburg (the center of the Russian film industry was in Moscow at that time).

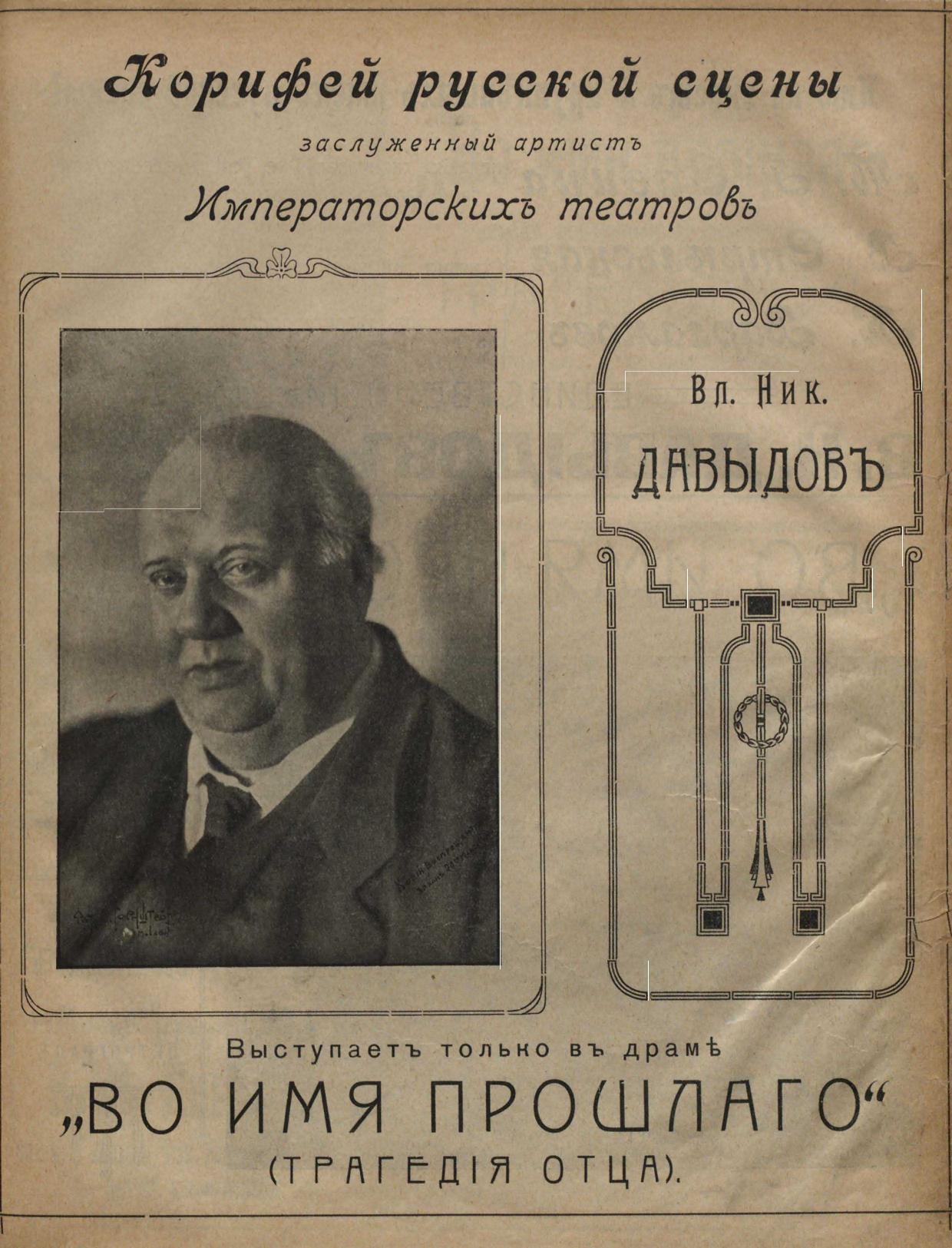

Vo Im’a Proshlogo/For the Sake of the Past (1915) is probably the most notable of the company’s early productions. Its plot is focused on Zakrevskii, an old land-steward who desperately loves his secret illegitimate son and steals the will that would disinherit him. However, it turns out that this young man was not Zakrevskii’s son, and his schemes ruined the life of the old man’s true daughter, who was to inherit the estate initially (“Novye lenty” [1916]). Bakhareva wrote the screenplay, drawing heavily on cinematic clichés; the majority of early Russian dramas were stories about illegitimate children, destroyed wills, and other melodramatic plots. For the Sake of the Past is significant, not due to its plot, but due to the casting: Zarkevskii’s part was played by the famous Russian theater actor Vladimir Davydov. His screen appearance was repeatedly highlighted in advertisements for the film and reviews (“Sredi novinok” [1916]).

Advertisement for For the Sake of the Past (1915) with the portrait of the “luminary of the Russian stage, honored artist of the Imperial theaters” Vladimir Davydov. Published in Sine-Fono no. 3 (1915).

It appears that Bakhareva placed a premium on famous names like many other film producers at the time. Aside from Davydov, she hired Lydia Yavorskaia who was very popular in the theater world (she starred in Bakhareva’s 1915 film Uragan strastei/The Hurricane of Passions). However, not all well-known people in St. Petersburg wanted to be involved in Bakhareva’s business. For example, in October 1916, the artist Aleksandr Benois wrote in his diary: “Miss Bakhareva called me and invited me to join some film enterprise that has pure artistic goals. I sympathize, but thanks to her amateur tone, I know for sure that it’s no God-damn use…” (Benois 28).

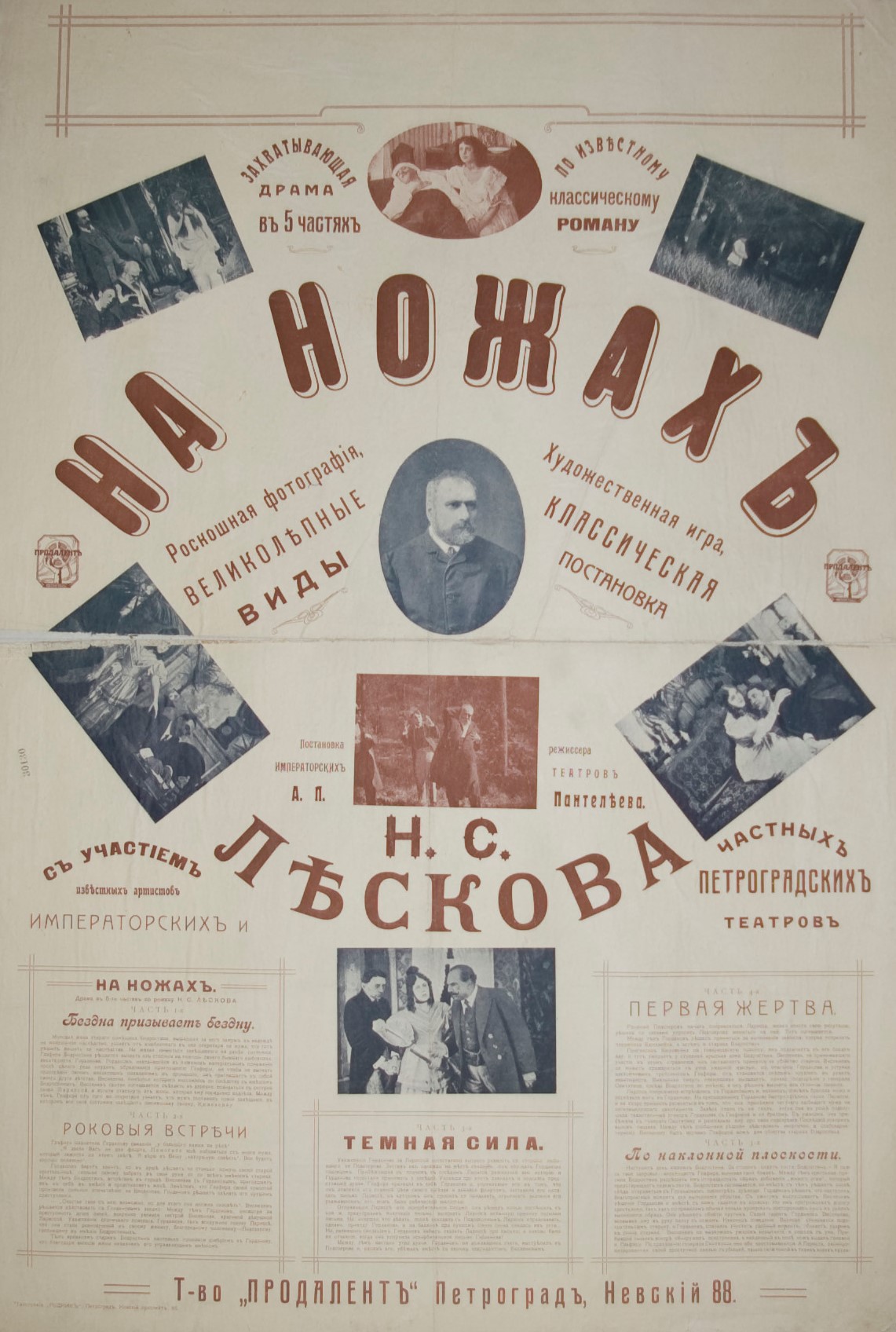

Overall, Bakhareva does not seem to have been an innovative or inventive screenwriter. Another film by her studio that attracted attention was Na nozhakh/At Daggers Drawn (1915), an adaptation of her grandfather’s novel of the same name. Bakhareva tailored Leskov’s book according to the period’s typical cinematic preoccupations. The socio-political and philosophical context was omitted, whereas the love affairs, rebuilt beyond recognition, became the basis of the picture. As a result, the titles of the film’s parts, indicated in the libretto (synopsis), had nothing to do with Leskov’s poetics and language: The Abyss Calls the Abyss, Fatal Encounters, Dark Force, The First Victim, and Down the Drain (“Novye lenty” [1915]).

One of the films written by Bakhareva, however, seems to have been rather uncommon in terms of its plot. A contemporary critic noted that Taina velikosvetskogo romana/The Mystery of the High Society Romance (1915) depicted “one of the recent criminal cases that had been investigated in Petrograd [that] made a lot of noise all over Russia” (“Sredi novinok” [1915]). Bakhareva likely relied on her past experience as a journalist while developing this script.

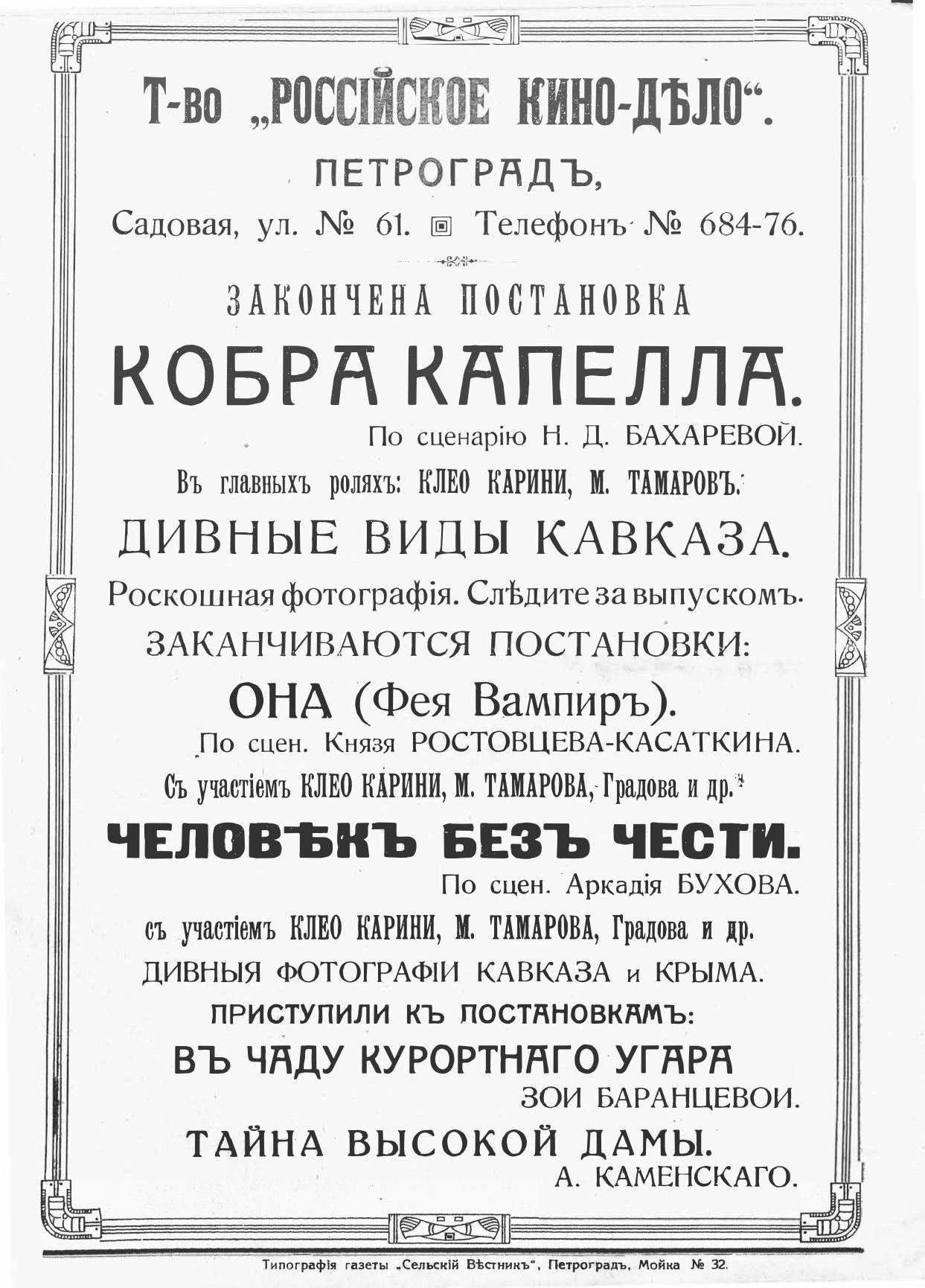

While Bakhareva did not give up writing scripts, she also began to hire professional writers such as Arkadii Bukhov, among others. Her main task as producer was likely “coordinating the shooting process” (“Khronika” [1917]), and that speaks well of her film producing skills. She could write herself and economize on the screenwriter’s salary, but she preferred to invest in the quality of the production. Moreover, she seems to have been generous in terms of business trips: the newspapers reported that, in the summer of 1917, her crew was spending time in the Caucasus shooting different picturesque places (“Erkan”; “Khronika” [1917]). She could have used her pavilion in St. Petersburg or done the shooting in the suburbs, but she organized this expensive trip in order to have on-location footage.

Advertisement for The Russian Film Business, which emphasizes that the films include “the marvellous [sic] views of the Caucasus.” Published in Teatr i iskusstvo no. 26 (1917).

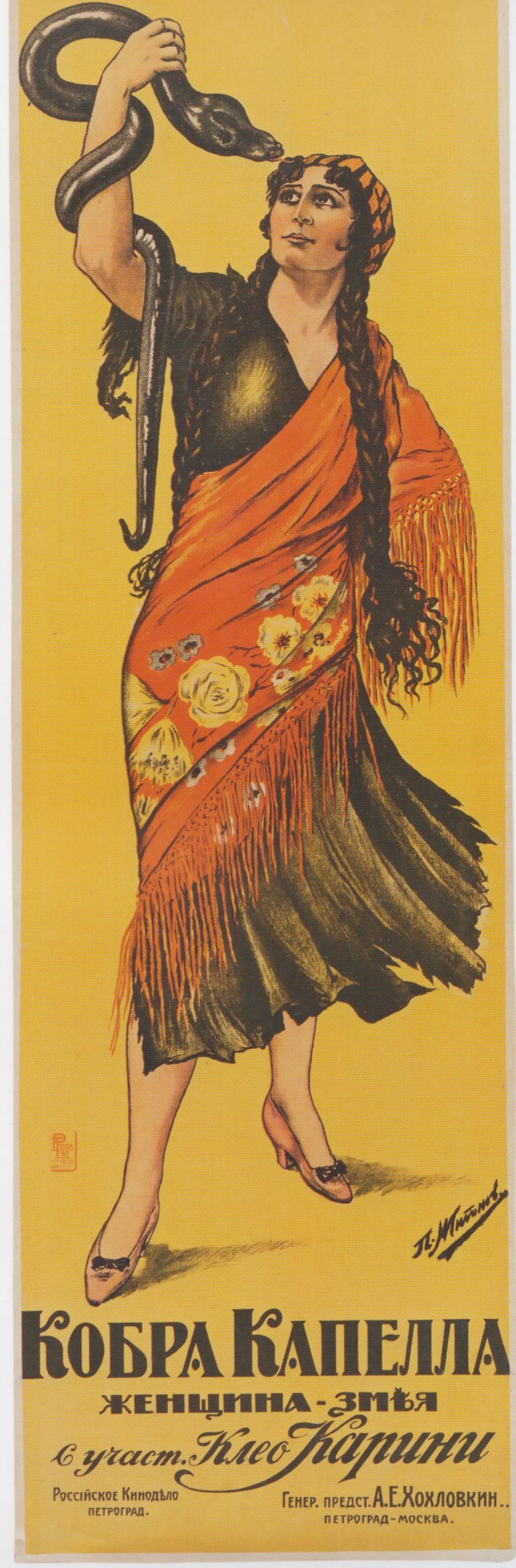

Poster for Cobra Kapella (1917) referencing Kleo Karini by name alongside her image. Reproduced in The Silent Film Poster in the State Museum of the History of Saint Petersburg Collection 1914-1919 (2018), p. 93.

There were no absolute hits among the pictures released by Bakhareva’s studio in 1916-1918. But the reviews prove that some of the films could be compared with films shot in Moscow by the major film studios. The film journal Proektor, which often published smashing reviews, tolerated Bakhareva’s productions. For instance, in the review of The Hurricane of Passions, a critic wrote: “This drama’s plot is typical and is not above the established cinema pattern. The film is directed fairly well and adequately shot. Yavorskaia’s acting is rather impressive…” (“Kriticheskoe obozrenie”). The review ends on a negative note about the actress’s make-up, but, for Proektor, it was very common to analyze every single one of a film’s weak spots in detail. The key point here is that Proektor chose The Hurricane of Passions for serious discussion.

It might well be that, in time, Bakhareva’s studio could have developed and produced films that would be better appreciated by such demanding journals as Proektor. But soon after the October revolution Bakhareva was forced to close her business. She recalls in her memoirs: “The Bolsheviks, upon coming to power, took my studio away from me and did not even allow me to keep the portraits of the artists I had filmed. The day of the atelier’s requisition coincided with the day of my mother’s burial; she had died of cancer” (Bakhareva 12). According to Andrei Leskov, Vera Noga, Bakhareva’s mother, died around March 18, 1918 (Leskov 130). Bakhareva moved to Ukraine and worked for the newspaper Iuzhnyi golos/The Southern Voice, which supported the White Russians (Bakhareva 46). In Kyiv, some of The Russian Film Business’s films, as the studio was then called, were produced: Taina Vysokoi Damy/The Mystery of a Tall Lady (1917), I snova zasvetilo solntse/And the Sun Became to Shine Again (1918), Ona/She (1918). Very little is known about these films, but according to Veniamin Vishnevskii’s filmography, The Russian Film Business started to shoot in Kyiv in 1917 (Vishnevskii 297). Bakhareva probably continued her film work there when her studio in St. Petersburg was closed in the spring of 1918. In any case, after 1918, Bakhareva did not have anything to do with the film industry.

Bakhareva spent many of the following years in Yugoslavia, but in 1945, the pro-Soviet Social Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was declared. Josip Broz Tito’s followers shot Bakhareva’s husband, Vasilii Poliushkin, and she had to leave the country. Soon after that, she moved to Argentina, where she died in 1958.

Bakhareva’s name is sometimes mentioned in reports on the émigré cultural life. For instance, a newspaper announced in 1930: “In Belgrade, a meeting in memory of Leskov, organized by the Union of Poets at the university, was very successful. […] Nikolai Leskov’s granddaughter, N. D. Bakhareva-Poliushkina, and his grandson, Colonel Ya. D. Noga, were present” (“Za rubezhom”). According to Bakhareva’s recollections, she cooperated with different newspapers and journals, such as Literaturno-Khudozhestvennyi Al’manakh/Literary and Artistic Almanac (based in Salzburg), Za Pravdu/For the Truth (in Buenos Aires), and Russkaia zhizn’/The Russian Life (in San Francisco) (Bakhareva 46). Additionally, the author of her necrology noted that, “N. D. Bakhareva has written a number of short stories, novellas, plays, and memoirs. Of these, the most famous are: The Sister Varvara (Sestra Varvara), The Unknown Paths (Puti Nevedomyie), The Surf (Priboi), and On the Big Road (Na Bol’shoi Doroge), which were published in the émigré press” (I.T.). However, during these years, literature and journalism were not Bakhareva’s primary occupations, and she did not become a genuinely notable figure in the Russian émigré culture. In Belgrade, she worked as the head of a boarding house for Russian female students and unemployed intelligent women (Burnakin 21-22).

This profile and a more detailed paper written in Russian (Kovalova 2011) rely heavily on Bakhareva’s papers held in the aforementioned Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European Culture. These papers include her memoirs and correspondence with the Slavic scholar William B. Edgerton. In the early 1950s, he found Bakhareva’s address and asked her to write memoirs about her famous grandfather. Bakhareva agreed to do so, but since she scarcely knew Leskov, she could not provide many new facts about his biography. Yet this manuscript and Bakhareva’s correspondence with Edgerton are impressive as documents representing her own biography and some details of the Russian émigré life. For example, in her letter to Edgerton from September 1953, Bakhareva wrote: “After the last illness, I have become completely incapacitated, I am about 70 years old. I have no funds. In these recent times, I have been leading [a] wretched existence. In other words, I cannot live without outside help” (Bakhareva 95). She was suffering from arthritis and had to dictate her manuscripts and letters. Edgerton managed to find some funding that would support Bakhareva in her financial difficulties; they exchanged letters for several years, and the correspondence became more and more affable and openhearted.

We still know very little of Bakhareva’s personality. Andrei Leskov had a low opinion of her, writing in his unpublished manuscript (held at The Institute of Russian Literature): “[She was] extremely ignorant (close to crudity), dissolute, very confident and creepy. She liked to drink, to borrow money (without return), knew how to flatter and please.” In the necrology published in Novoe Russkoe Slovo, the most influential Russian émigré newspaper in America, she is described very differently: “Having inherited from her grandfather a literary talent and being attracted to literature, she soon left the stage for writing. The genres of her works are diverse and rich: fiction, dramatic works, theater criticism. […] With her death, the Russian colony in Buenos Aires has lost a major cultural power” (I.T.). This necrology probably exaggerates Bakhareva’s literary achievements, but it does not even mention her work in cinema, where she has genuinely placed herself on record. Very few people in the émigré community knew that aside from being Nikolai Leskov’s granddaughter, Bakhareva was the first female film producer in Russia.

The author wishes to thank Maya Kucherskaya for generously sharing her notes taken at the Manuscript Department of the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House).

This profile is dedicated to the blessed memory of the outstanding Slavic scholar Hugh McLean (1925-2017), who, with all possible care and generosity, helped the author to carry out her research on Bakhareva and shared copies of her manuscripts, without which this work would have been impossible.