New publication: Musidora qui êtes-vous? (2022) (Reviewed by Aurore Spiers)

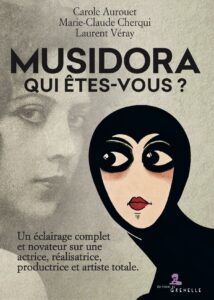

Musidora qui êtes-vous? Edited by Carole Aurouet, Marie-Claude Cherqui, and Laurent Véray (Paris: Editions de Grenelle, 2022). 274 pages. 35 euros. https://www.editionsdegrenelle.fr/musidora/

Review by Aurore Spiers

Musidora qui êtes-vous? Edited by Carole Aurouet, Marie-Claude Cherqui, and Laurent Véray (Paris: Editions de Grenelle, 2022).

While Musidora remains best known for playing Irma Vep in Les Vampires (Louis Feuillade, 1915), a new book published in French sheds light on Musidora as an “artiste totale.” Edited by Carole Aurouet, Marie-Claude Cherqui (Musidora’s great-niece), and Laurent Véray, Musidora qui êtes-vous? consists of a collection of twenty-three essays written by scholars mostly based in France. In their brief introduction, Aurouet, Cherqui, and Véray explain that their goal is twofold: to reflect on Musidora’s enduring mythical status in visual culture; and to examine all aspects of Musidora’s career, not only as an actress, but also as a writer, playwright, director, producer, painter, and archivist for the Cinémathèque française. Musidora qui êtes-vous? is therefore divided into four chapters focusing on Musidora’s early career at the music hall; her novels, plays, and children’s stories, and her relations with Colette and other literary figures; her many contributions to cinema in France and beyond; and her afterlives in popular culture, contemporary art, and feminist media, among others. At the end, an illustrated timeline from Musidora’s birth in 1889 through her death in 1957, and a selected bibliography that includes scholarship in both French and English, provides further references for anyone interested in learning more about Musidora.

The detailed account of Musidora’s many lives and careers in Musidora qui êtes-vous? is both timely and inspiring. But of particular interest to the readers and authors of the Women Film Pioneers Project (WFPP) will be the three essays on the films produced by Musidora in Spain in the 1920s, namely Vicenta (Musidora, 1919), Pour Don Carlos (Musidora and Jacques Lasseyne, 1921), Sol y sombra (Musidora and Jacques Lasseyne, 1922), and La Tierra de los toros (Musidora, 1924). With the notable exception of WFPP contributor Annette Förster in her book Women in the Silent Cinema: Histories of Fame and Fate (Amsterdam University Press, 2017), few scholars have so far written about Musidora’s Spanish films, which were long considered lost or unavailable. In Musidora qui êtes-vous? new film restorations and archival findings make it possible for Annette Förster, Béatrice de Pastre, and Lucas Bruneau to revisit these films with an eye not only to Musidora’s acting performances but also to the realism of her visual aesthetic.

Shot at least partly on location in Spain, Vicenta focuses on the misfortunes of a young woman (Musidora) who leaves her native Basque Country for a shallow life of luxury in Paris. Béatrice de Pastre discusses Vicenta based on a fragment identified in the collections of the Cinémathèque française in 2016. That fragment is admittedly short—only nineteen minutes of the almost hour-long film survive—but valuable to understand Musidora’s use of natural settings, as well as her ambitions as the director, screenwriter, and producer of her own films more broadly. Along similar lines, Förster uses a recent restoration by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, the Cinémathèque française, and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, to reassess Musidora’s aesthetic in Pour Don Carlos, which was also shot on location in the Basque Country, with non-professional actors from the region. Pour Don Carlos, adapted from a popular novel by Pierre Benoît, recounts the story of a female army officer (Musidora) fighting for Don Carlos during the Third Carlist War (1872–6). Because the film was co-directed by Jacques Lasseyne, it is admittedly difficult to attribute specific stylistic elements to Musidora alone. Yet Förster recognizes in the film’s realism the mark of Musidora’s creativity, which, Förster argues, was most likely inspired by André Antoine. Drawing on extant interviews, and on not only Vicenta and Pour Don Carlos, but also Sol y sombra and La Tierra de los toros, both of which focus on the romance between a young woman (Musidora) and a torero (Musidora’s real life lover and famous bullfighter Antonio Cañero), Lucas Bruneau also shows that Musidora shared an interest in the photogénie of natural landscapes with such realist filmmakers as Henri Pouctal, Albert Capellani, and Louis Delluc.

By making connections between Musidora and some of her contemporaries, Musidora qui êtes-vous? begins to contextualize Musidora’s Spanish films within the French film culture of the 1920s. At the same time, although the authors in Musidora qui êtes-vous? do not explicitly say this, Musidora’s Spanish films might have offered more compelling depictions of women than other (male-directed) realist films from around the same time. When Pastre compares the eponymous character in Vicenta to Emma Bovary, for example, Vicenta joins in the same constellation of feminist films as Germaine Dulac’s La Souriante Madame Beudet (1923), about a married woman (Germaine Dermoz) dreaming of a more exciting life. As Musidora qui êtes-vous? shows, Pour Don Carlos, Sol y Sombra, and La Tierra de los toros also feature complex, fierce, and independent women, all played by Musidora.

A valuable contribution to women’s film history, Musidora qui êtes-vous? recasts Musidora as a filmmaker concerned with the issues of her time, mainly realism, photogénie, and perhaps even feminism. The book also opens up new, fascinating avenues of research into, among others, Musidora’s crossdressing performances on stage, her literary production, and the intermediality of her work from the 1910s until the 1950s. It is, indeed, well worth the read; cinema’s first vamp comes to the fore as a multifaceted artist whose many contributions to film and other forms of media throughout the twentieth century deserve still more attention.

See also: Annette Förster’s WFPP profile on Musidora.

Aurore Spiers (she/her) is a Humanities Teaching Fellow and Lecturer in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. She received her PhD from Chicago in 2022. Her first book project studies women’s labor in the French film archives and libraries from the 1920s through the 1970s. She is also a contributing editor and country coordinator (France) to the Women Film Pioneers Project.