The historiography of silent cinema in Latin America tells a story of good fortune in the face of adversity, enterprising individuals, and collective frustrations. Until recently women were virtually absent from published histories, however; this omission from the major works in Latin American film historiography is evidence of the way in which women’s work has been made invisible in the main tradition. Thanks to the interest and persistence of a number of film scholars, however, we can now celebrate the names of the Latin American women who made significant contributions to silent film in producing, screenwriting, acting, editing, and directing, as well as in film journalism and motion picture exhibition. Reporting on and reevaluating the careers of these women has been a very complicated job primarily due to the dearth of written materials and extant films. In the following career profiles we examine the work of a number of women whose participation in the development of silent film practices has recently been documented: the Brazilian film pioneer Carmen Santos; the Chileans Alicia Armstrong de Vicuña, Gabriela von Bussenius Vega, and Rosario Rodríguez de la Serna; the Peruvians Ángela Ramos de Rotalde, María Isabel Sánchez Concha Aramburú, Teresita Arce, Stefanía Socha; and the Mexicans Mimí Derba, Adriana and Dolores Ehlers, Cándida Beltrán Rendón, Cube Bonifant, Elena Sánchez Valenzuela, Adela Sequeyro, and Adelina Barrasa. Research on women in the Argentinean and Peruvian film industries remains at a less developed stage. Paulo Paranaguá has identified the participation of two Argentinean women filmmakers: Emilia Saleny (Niña del bosque, 1917, Paseo Trágico, 1917, and Clarita, 1919) and María V. De Celestini (Mi derecho, 1920).1 Moira Fradinger also mentions René Oro and Elena Sansinena de Elizalde in the Women in Argentine Silent Cinema section below, indicating that further research must be done on both of these pioneers.

Women’s participation in the early Mexican motion picture industry has been reclaimed only recently in the wake of broader political and cultural formations. These include Mexico’s Second Wave feminist movement in the 1970s; the celebration of the “Year of the Woman” in 1975; the founding of two world-renowned film schools—the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos (CUEC) in 1964 and the Centro de Capacitación Cinematografica (CCC) in 1973; the formation of the first and only women’s film collective in Mexico, the Colectivo de Cine Mujer (1975–1987); and the emergence of a vibrant group of film scholars in the 1980s and 1990s, who were actively dedicated to the recovery of a century of Mexican film history. As a result of these diverse developments, a range of analytical approaches to the history of women in Mexican film has emerged. 2

Examples of early scholarship on the silent period include Aurelio de los Reyes’s 1986 Filmografía del cine mudo mexicano, 1896–1920 and Gabriel Ramírez’s 1994 Crónica del cine mudo mexicano. More recently, a number of published monographs have recovered and reevaluated the work of two Mexican women directors who made significant contributions to Mexican silent cinema: Ángel Miquel Rendón’s Mimí Derba (2000) examines the participation of Derba in the areas of production, direction, and distribution while Eduardo de la Vega and Patricia Torres San Martín’s Adela Sequeyro (1997) evaluates the work of Sequeyro in film journalism and in producing, acting, and directing during the transition between silent and sound cinema.

In other national contexts, Ana Pessoa’s 2002 Carmen Santos: O cinema dos anos 20,brings to light the life and work of Brazilian filmmaker Santos, and in 1993, the Chilean film journalist Eliana Jara Donoso published one of the most important histories of the silent period in Chile, Cine mudo chileno, which included information on women who participated in silent cinema production in Chile. Thanks to these works, we are now able to make a more precise map of the participation of women in the silent cinemas of Mexico, Brazil, and Chile.

A major obstacle to scholarship is the absence or loss of materials. Even in the case of Mexico, researchers have not been able to rely on the films themselves since the majority of silent Mexican motion pictures have disappeared or were destroyed. Dramatically, a devastating fire at the Cineteca Nacional, Mexico’s national film archives, destroyed over 6,000 films and ancillary materials in 1982. Without the films themselves, scholars have had to rely on other archived materials. The Chilean case is as unfortunate. Only a few Chilean silent films out of more than eighty feature-length films produced between 1898 and 1936 survive. The history of the period must therefore be constructed from photographs, newspaper clippings, essays by filmmakers, and published reviews of films. In the words of Chilean scholar Eliana Jara Donoso, echoing Giuliana Bruno on the work of the Italian filmmaker Elvira Notari, the situation of Latin American silent cinema remains a “ruined map.” 3

Comparative Industrial Conditions

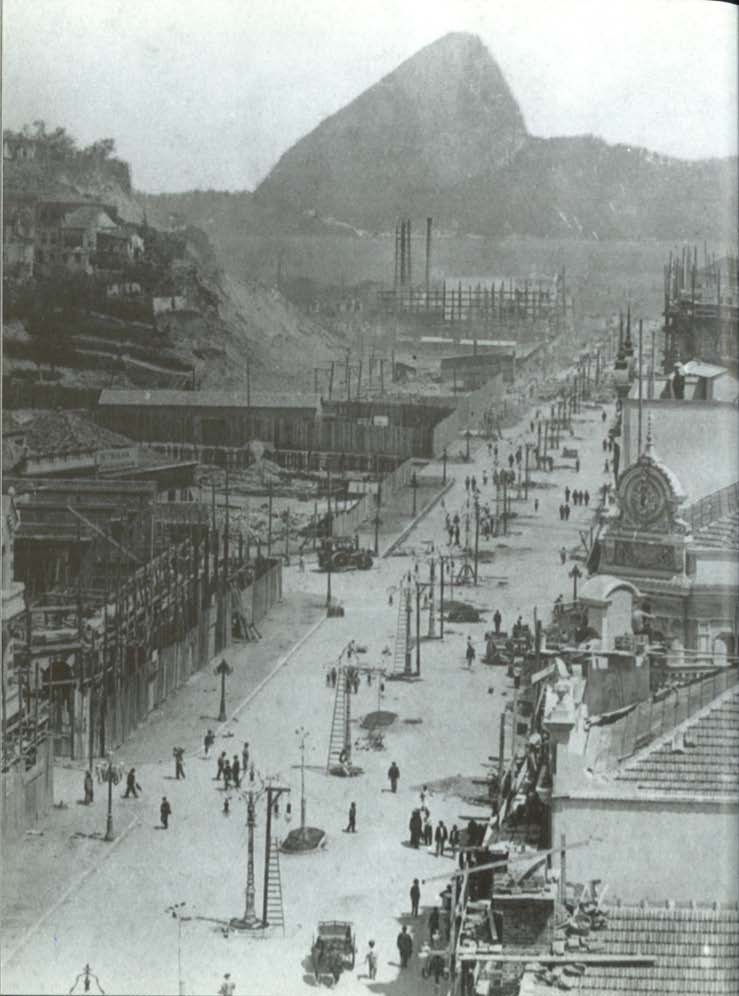

Understanding the conditions for silent cinema in Latin America depends upon a grasp of the culture industries as part of the new global capitalist interdependence of world nations in the early twentieth century. The Lumière brothers introduced motion pictures to major Latin American urban audiences in 1896, only a few months after the premiere of their cinematograph in Paris on December 28, 1895. French and enterprising Latin American film producers immediately began photographing local events and subjects and distributing these actualities across the region. While a number of Latin American countries quickly developed domestic film industries, these industries were dependent on Europe and the United States for raw stock and motion picture technology as well as for 35mm films to fill exhibitors’ screens. By the 1920s, Latin America was Hollywood’s largest export market and companies like Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO set up distribution centers in Mexico City and Rio de Janeiro in an effort to circulate their films to local exhibitors. In spite of the dominance of Hollywood, at least two Latin American film industries achieved some measure of success in their own domestic market. In Brazil, 1,685 films were made during the silent period and in Mexico filmmakers left a legacy of over a hundred silent fiction features and shorts and documentary shorts and features made between 1898 and 1928.

The histories of the various national film industries testify to the fact that each country found a way to build its own cinematic identity in the face of Hollywood’s globalizing competitive strategies. For example, the embryonic Mexican film industry was a private venture funded by independent Mexican entrepreneurs who were instrumental in initiating the national film industry. Two important production periods defined Mexican silent cinema: 1896 to 1915 and 1917 to 1931. The first phase saw experimentation with fictional genres modeled on Italian and North American films. When narrative filmmaking came to a virtual standstill during the Mexican Revolution, 1910–1917, filmmakers perfected their craft through the production of documentaries that chronicled the encounters between revolutionary forces and the state’s federales. The end of the war’s military phase in 1917 and the ensuing economic and social stability allowed for the establishment of a Mexican studio system, the development of Mexican feature-film production, and the emergence of cinematic and narrative conventions that were to endure for decades. But the earlier Italian and North American influences were tempered by a vibrant postrevolutionary intellectual, political, and aesthetic nationalism. It was this second period of silent film that finally provided Mexican women with the chance to help make a national film industry. In 1917 the popular theatre actress Mimí Derba established Azteca Film Company with Enrique Rosas and produced five feature films in that one year. One of Derba’s primary objectives was to produce a “national cinema” that would provide European and North American audiences with a new image of Mexico to counter Hollywood stereotypes of the pelado (a lower-class, uneducated male) and la china poblana (a colorfully dressed village girl), types visible in US films such as Across the Mexican Line (1911), The Mexican Defeat (1913), Captured by Mexicans (1914), and The Mexican Chickens (1915). 4

Sisters Adriana and Dolores Ehlers also contributed to the refashioning of Mexican silent film with their newsreel-style documentaries that challenged conventional images of Mexico. Their films also countered post-revolutionary depictions of the country as a socially and economically backward nation populated by colorfully dressed Indians. The Ehlers’s newsreels instead presented images of a vibrant, cosmopolitan urban society. The sisters also made a contribution to the technological development of the entire Mexican film industry through their distribution of cameras and projectors produced by a US firm, Nicholas Power Company. 5

Cinema emerged in Brazil at the turn of the century, primarily in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, according to historian Ana Rita Mendonça. The first production and exhibition entrepreneurs in the Brazilian film industry were European immigrants, mainly Italians, who promoted the idea that European films were technically better than those made in Brazil. According to Mendonça, until the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, the only local Brazilian film producers were the Italian-Brazilian Segreto brothers. However, by the end of the first decade, there were cinema venues in other Brazilian cities that featured the screening of regional programs (Mendonça 1989, 84). In Recife, the capital of the state of Pernambuco located in Brazil’s Northeastern region, more than thirty titles, including thirteen short and feature fiction films and approximately twenty nonfiction short films were produced. During these early years, a number of production companies were formed, and ten of them were able to produce and exhibit at least one film. In Brazilian film history, this period is known as “Ciclo do Recife”/“The Recife Cycle,” one of the so-called “regional cycles” of the silent period. 6

While foreign films dominated the market in Brazil, as in Mexico, the most popular films were national productions composed of noticiarios, or newsreels, and posados, or feature films, primarily of the thriller genre. In the first decade, more than 100 of these nationally produced films circulated all over the country. However, by 1911, the apparent success of the national film industry collapsed in the face of increased competition from foreign producers and distributors, and Brazilian distributors turned to exhibiting foreign films on which they could make more money.

For a period of almost twenty years the Chilean film industry was able to maintain continuous production levels in several locations, thus creating a film culture with regional identities in cities such as Valparaíso, Antofagasta, Punta Arenas, and Iquique, the city where the very first films were made as early as 1897. Chilean motion pictures were shown on the screens of the “biographs” in the big cities and elsewhere in small regional venues. As with the case of Brazil and Mexico, these films were popular because they were national productions and had “no reason to envy foreign productions,”a phrase repeated in advertisements.

Ultimately, the success of the Mexican, Brazilian, and Chilean silent film industries was dependent on one or more of the following: the heavy industrialization of the industry, substantial state support in the form of quotas and tariffs on imported foreign films, and significant tax breaks. The most successful national industries were those that aimed for a limited domestic market, but in the end these small film industries were at the mercy of political and economic upheavals. Finally, although these three countries stand out because they were able to start domestic motion picture industries during the silent era, primarily by capitalizing on national themes and stories, they never approached the size of Hollywood’s industrial machine nor did they challenge its ascendancy over the Latin American film market. It is safe to say that although we distinguish successful national efforts and projects in the silent era, it is clear that the US motion picture industry inhibited the growth of individual domestic film industries.

Comparative Social Contexts

While women of the middle and upper classes were enjoying newfound freedoms during the 1920s and 1930s in many Latin American countries, the economic and cultural environments in which they moved were still quite restricted for them. Thus, it remained difficult for women to freely enter emerging labor markets such as that provided by the motion picture industry and to move up through the ranks in the new film professions. In light of this social labor context, we must ask the following question: What cultural and social issues allowed or restricted women’s entrance into emerging film industries in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico? Where did women find work in the film industry? Two general observations can be made here.

First, these women worked in a social, institutional, and economic environment that was explicitly designated as a male arena. We recognize the extreme exclusion of women, for example, in the Chilean state regulations that prohibited young women from even entering motion picture theatres unless they were chaperoned. The only women who were able to work in the public sphere were those who, due to their social standing, already commanded a level of economic independence. These were not working-class but were educated women representing a social class that already had access to public cultural space. Second, we find that in Mexico, Brazil, and Chile women entered the emerging film industries primarily through avenues such as the theatre and film journalism, suggesting the need for a comparison between points of entry. In a number of cases, women moved into the film industry through their work as film journalists in national and local newspapers and periodicals. Film journalism was a relatively open territory through which a number of male as well as female filmmakers moved into the cinema. For example, in Mexico during the 1920s, Elena Sánchez Valenzuela, the founder of the first film archive in Latin America as well as the director and actress Adela Sequeyro, both inaugurated their careers as columnists for Mexico City newspapers at a time when writing about motion pictures was beginning to be considered an important profession (Torres San Martín 1992). In addition to El Demócrata, other leading Mexico City newspapers such as Excélsior and El Universal published sections devoted to cinema. Women writing for columns in these papers during the 1920s and 1930s, in addition to Elena Sánchez Valenzuela and Sequeyro, included María Celia del Villar as well as Cube Bonifant.

In Mexico and Brazil, the alliance of film production companies with the major national newspapers also contributed to the fluidity with which women crossed between the two professions in the era of silent cinema. For example, in Mexico a number of producers worked with El Demócrata in the early 1920s in an attempt to create Mexican film stars. Actresses such as Dolores del Río and Lupe Vélez emerged as icons of international cinema and important figures in Hollywood cinema during this period (Ramón 1993; De los Reyes 1996b; Hershfield 2008). According to Jara Donoso, the Chilean silent cinema distinguished itself through the participation of theatre performers and well-known writers and artists, some of whom were women. A few of these women were from the elite sectors of society while others came from theatre, where they worked as cuple dancers or cupletistas, singers, and vaudeville artists. 7 These activities were not always viewed favorably by a moralistic society that worried about the behavior of young women. In addition to these actresses, at least three women have been identified as directors of Chilean feature-length films, according to Jara Donoso. She notes that it was a woman, Gabriela von Bussenius, who made the second feature-length Chilean film in 1917 at the exact moment when film production was becoming a legitimate industry (Jara Donoso 1994, 34). Years later, in 1925 and 1926, two Chilean women, Alicia Armstrong de Vicuña and Rosario Rodríguez de la Serna, would follow in her footsteps.

Although we find clusters of women filmmakers in Mexico, Brazil, and Chile, and isolated cases in Colombia (Kathleen Romoli) and Peru, it is difficult to affirm a women’s cinema, feminist cinema, or even an oppositional cinema emerging from women’s conditions of social inequality. Follow the links below for descriptions of each career. We see that the success of women in motion picture production was sometimes due to chance or luck as well as to their dedicated struggle to overcome social conditions adverse to women’s full social participation.

See also: Cleo de Verberena, Eva Nil

Notes:

- Paulo Paranaguá, “Women Film-Makers in Latin America,” Framework 37 (1989): 129-139. ↩

- Luz Cecilia Greaves, “La mujer como cineasta en México,” PhD dissertation, Universidad Intercontinental, 1994; Ana María Amado Hernández, et al. Colectivo cine mujer (Mexico City: Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica, 1982); María Guadalupe Benítez Sauri and Martha Leticia Villafuerte Aranda, “Del hogar a la realización fílmica. El caso de dos directoras (Matilde Soto Landeta y Marcela Fernández Violante),” B.A. thesis, Universidad Latinoamericana, Escuela de Comunicación, 1993; Ana Cecilia González Velasco, “La prostituta en el cine mexicano,” B.A. thesis, Departamento de Comunicación, Universidad Iberoamericana, 1979; Luis Bernardo Jaime Vázquez, “Cine al borde de un ataque de mujeres: apuntes para una filmobibliografía de las directoras del cine Mexicano (1917–1999),” B.A. thesis, ITESO, 2001; Angélica Patricia Martínez Sustayta, “Análisis de algunos personajes femeninos en el cine mexicano. Visión de cuatro directores,” B.A. thesis, UNAM, 1989; Octavio Moreno Ochoa, “Catálogo de directoras de Cine en México,” 2 vols, B.A. thesis,UNAM, 1992. ↩

- Giuliana Bruno, Streetwalking on a Ruined Map (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1993). ↩

- Emilio García Riera, México visto por el cine extranjero. vol. 1 (Mexico : D.R. Ediciones Era, 1987). ↩

- J. M. Sánchez García, “Apuntes para una historia de nuestro cine,” Novedades, Feb. 26, 1940. ↩

- Luciana Corrêa de Araújo, “Modernity and Morality: Female Film Stars and Feminine Characters in Regional Silent Cinema,” Paper Presentation, Woman and Silent Cinema IV, Guadalajara, México, June 2006. ↩

- The cupletistas were the cuple dancers. The cuple is the contradiction resulting from traditionalism and modernity in Spain from the earliest part of the twentieth century. Its musical source comes from nineteenth-century Spain, and its etymology is from the French word couplet. ↩

Additional Research Reports

The Trace of the Feminine in Chilean Silent Era

By Mónica Villarroel

Translated by José Miguel Palacios

In Chile, the presence of the feminine world was prominent both in the film chronicles of the silent era and in censorship. It was a common practice for exhibitors to invite the press and local elites to the first screenings, including authorities and ladies and gentlemen of high society, as recounted in numerous publications. Lucila Azagra, in a chronicle titled “Los gustos del público” [The Tastes of Audiences], referred to the heterogeneity of preferences that film spectators had toward 1918, distinguishing three groups: “el [público] de los que en las obras buscan ideas, el de los que buscan pasión, y finalmente el de los que al arte le piden acción o movimiento” [the audience that looks for ideas in the works, the one that looks for passion, and finally, the one that demands action and movement from art]. The first group is the most reduced and was formed by thinkers, sociologists, and men of literature. The second group was formed mainly by women; and the third one, the largest, “el grueso del público” [the majority of viewers], was formed by “las gentes vulgares de todas las edades y condiciones, por los obreros, por los estudiantes, por los agricultores, por los comerciantes, por los empleados de oficina, por los industriales y, en general, por todas aquellas personas de alta o baja cuna que no han logrado intelectualizarse lo bastante” (…) [the vulgar peoples of all ages and conditions, by workers, students, farmers, businessmen, office employees, industrial workers, and in general, by all those who, whether high or low class, have not been cultured enough], according to the La Semana Cinematográfica (“Editorial” n.p.). I highlight here the existence of a woman chronicler and the explicit reference to gender as a way to classify spectators.

On another hand, one of the early manifestations of censorship was the one exercised by the Liga de Damas Chilenas [Chilean Ladies League], an organization established in Santiago on July 10, 1912, whose first task was to “combatir la licencia de los espectáculos y pronto organizó una Comisión de Censura Teatral compuesta de señoras y caballeros de alto prestigio social y de reconocida ilustración y experiencia” [dispute the licensing of spectacles. Soon it organized a Commission of Theatre Censorship formed by ladies and gentlemen of high social prestige and recognized culture and experience], according to El Eco de La Liga de Damas Chilenas (1915, 2). The League, supported by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, realized a systematic campaign in its newspaper, El Eco de la Liga de Damas [The Echo of the Ladies League], later called La Cruzada [The Crusade]. Amalia Errázuriz de Subercaseaux was designated president. Her goal was to censor those works deemed immoral in Santiago and nationally. The act of censorship was exercised by the Committee of Censorship, which evaluated theater and film productions. Three categories were established, first in relation to theater, but they were later applied to cinema as well: “buenas o aceptables para niñas; regulares o aceptables solo para señoras y malas e inconvenientes para unas y otras” [good or acceptable for girls, regular or acceptable only for married women, and bad and inconvenient for both], according to El Eco de La Liga de Damas Chilenas (1915, 2).

The League watched over the cinema theaters, especially those frequented by the elite of Santiago: the Royal (or Kinora) and the Unión Central. Besides direct censorship, they published texts that condemned cinema. In June 1917, for instance, they reprinted an article from El Mercurio that warned the reader about the dangers of cinema, stressing how inconvenient it is for women and children to see films.

On the other hand, local production was small if compared to the abundance of foreign films on national screens. Commissioned works were a common practice, and so was the alternation of fiction and documentary by production companies that were equally devoted to both modes. Family companies and the arrival of immigrant technicians marked the realization of local productions, from the Lumière cameramen to the Italian Salvador Giambastiani Dall’Pogetto, with a special predominance of French technicians. Giambastiani founded the Chile Film Co. (also cited as Giambastiani Film), whose first production was, in 1917, La agonía de Arauco o el olvido de los muertos [The Agony of Arauco or the Forgetting of the Dead], directed by his wife Gabriela von Bussenius Vega, sister of the cameraman Gustavo von Bussenius, who worked with the Italian. When Giambastiani died Gustavo and Gabriela took over the company.

I also highlight Rosario Films, a company that produced two of the few films directed by women, Malditas sean las mujeres [Damned be women] (1925) and La envenenadora [The Poisoner] (1929), both by Rosario Rodríguez de la Serna.

It is worth mentioning that in Chilean fiction film, melodrama stands out as the main genre. Nonetheless, the films’ scarcity should also be noted. The aesthetics were realist and naturalist, with some stories based on national heroes where a stereotyped criollismo anchored in nationalism was dominant, a tendency that coexists with cosmopolitan desires manifested mainly in documentary. As of now, eighty-two fiction films and two animated works are known to have been produced between 1910 and 1934, of which only three complete features are extant: El húsar de la muerte, 1925; Canta y no llores, corazón, 1925; and El Leopardo, 1927, as well as fragments from Vergüenza (1925) and Manuel Rodríguez, the first fiction film, dated on 1910. Out of all these productions, four were made by women directors Gabriela von Bussenius Vega, Rosario Rodríguez de la Serna, and Alicia Armstrong de Vicuña.

It should be noted too that the construction of the nation in documentary images of Chilean silent cinema alludes to an aesthetic associated with the oligarchy. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the emphasis is on the display of the lives of aristocrats, military, civilian and religious authorities, with their quotidian rites, parties, and social events. The learning of French, first, and English, secondly, constituted an element of social distinction between the elites and the emergent middle classes in Chile. This was the case of writers such as Inés Echeverría, Iris, who published in French. Likewise, Paris was the main reference for the elite, as the model of modern metropolis and avant-garde. Women fashion from Europe can be seen in the few documentary images that have survived, even though the presence of women in views and actualities is rare.

Bibliography

Bongers, Wolfgang, María José Torrealba and Ximena Vergara, eds. Archivos i letrados. Escritos sobre cine en Chile: 1908-1940. Santiago: Cuarto Propio, 2011.

El Eco de La Liga de Damas Chilenas vol. 3, no. 57 (1 January 1915): 2.

Jara Donoso, Eliana. Cine mudo chileno. Santiago: Self-published, 1994.

“Editorial.” La Semana Cinematográfica 2 (16 May 1918): n.p.

Vicuña, Manuel. La belle époque chilena: alta sociedad y mujeres de élite en el cambio de siglo. Santiago: Editorial Catalonia, 2010.

Villarroel, Mónica. “El mapa del cine temprano en Chile: hacia una configuración del asombro en el contexto latinoamericano.” Revista Aisthesis 52 (2012): 9-30.

Women in Argentine Silent Cinema

By Moira Fradinger

A vibrant and growing Italian community settled in Argentina as far back as the early nineteenth century and rapidly increased at the turn of the century with a massive flow of immigrants. As in other countries of the continent, Italians disembarked in Buenos Aires with the hope to “make it in America.” But unlike in other countries, they were not only manual laborers. They were also professionals, artists, photographers, musicians, theater actors, and, not to be forgotten, political exiles coming from the ranks of communist and anarchist turn-of-the-century Italy. Unlike in New York, Italians disembarking in Buenos Aires mostly came not from the South but from the North; they all found a country not “made” but “to be made.” Some of these immigrants were just touring through Buenos Aires and decided to remain in the teeming city that was barreling “full steam” towards industrial modernity. Although the overwhelming majority of these travelers were Italians and Spaniards, the wave also brought every kind of European.

Few cities in the world were so foreign in the make-up of their population at the time. The municipal census of 1909 shows Buenos Aires had 1,231,698 inhabitants, of which 670,513 were Argentine, 561,185 were foreign (46%). Among the latter, 174,291 were from Spain and 277,041 were Italians (“El Censo de 1909,” 109). It is estimated that from 1869 to 1915, 45% to 53% of the population of Buenos Aires remained of foreign origin, and 80% was composed of foreigners and children of foreigners. By 1914, 80% of immigrants to Argentina were either Italians or Spaniards and Italians composed from 25% to 32% of the foreign population of Buenos Aires (Argentina National Census 1914, 83-94). Business and industry largely depended on this immigrant wave. The film industry was no exception. The “kinescope” entered the country thanks to the German Federico Figner, who also filmed the first views of the city. The photographic equipment firm Lepage pioneered the importation of Gaumont cameras: the owner, Enrique Lepage, was Belgian. Lepage’s collaborator, Eugenio Py, filmed the first short documentary, La bandera argentina/The Argentine Flag (1897) and the first professional news report, El viaje a Buenos Aires del Dr. Campos Salles/Dr. Campos Salles’s Trip to Buenos Aires (1900). Py was French. Another of Lepage’s collaborators, the Austrian Max Glucksmann, was the pioneer of the production and exhibition of films in the Argentine capital. Mario Gallo, an Italian, directed the first Argentine fiction film, La Revolución de Mayo/The May Revolution (1909). Federico Valle, another Italian, filmed the first weekly newsreel (Film Revista Valle, 1916-1931) (Marrone 2003, 27-57; Finkielman 2004, 5-31; Zago 1997, 1-23; Caneto et al. 1996; Couselo 1984, 11-22).

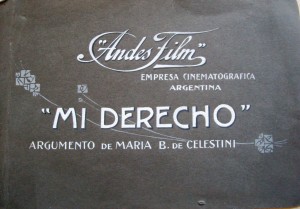

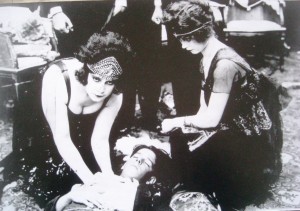

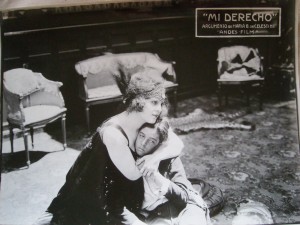

Three women working in the film industry during the silent period have appeared in citations, but little is known of them. María B. de Celestini filmed Mi Derecho in 1920 and is invariably mentioned in film histories, but so far we do not possess any of her biographical information. Her film seem to have been destroyed in a fire, although the Cinemateca Argentina has production stills from Mi Derecho. Paraná Sendrós, in his article for the newspaper Ámbito Financiero (1988), mentions that the film had to be finished by the director of photography Alberto Biasotti, a major associate of the Ariel studios in Buenos Aires (n.p). To judge from the stills, the film was produced by Andes films and the story was written by Celestini, whose child seems to have been one of the actors. From the images, we can reconstruct that the film is a moral drama involving a woman perhaps of “low life” or “dubious reputation,” as well as a child and a man. The woman is dressed for a cabaret performance of some kind; the child is beaten by the man and the woman is shown consoling the child who lies on the floor of what we presume is the cabaret where she works.

René Oro (also Renée) is also mentioned as having directed the documentary film La Argentina (1922), but more research into this film and other possible documentaries is necessary (Finkielman 48). La Patria mentions Elena Sansinena de Elizalde as having written and directed Blanco y negro/ Black and White, which premiered on November 22, 1919, at the Grand Splendid Theater (“Blanco y Negro” 5). The film is usually listed as having been directed by Francisco Defilippis Novoa in 1919, and starring Victoria Ocampo, who by then was a friend of Sansinena and who would later become a famous writer (Zago 28). Daughter of land-owners in the province of Buenos Aires, Sansinena was the founder and president of a vibrant all-female cultural association in Buenos Aires, La Asociación Amigos del Arte (1924-1942), which had a strong impact on the cultural scene of the city.

Bibliography

Argentina National Census 1914. Redalyc vol. 5, no. 8 (October 2008): 83-94.

“Blanco y Negro.” Rev. La Patria (9 November 1919): 5.

Caneto, Guillermo, et al. Historia de los primeros años del cine en la Argentina, 1985-1910. Buenos Aires: Fundación Cinemateca Argentina, 1996.

Couselo, Jorge M., et al. Historia del Cine Argentino, Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina, 1984.

“El Censo de 1909 de la ciudad de Buenos Aires.” Redalyc vol. 5, no. 7 (April 2008): 109.

Finkielman, Jorge. The Film Industry in Argentina: an Illustrated Cultural History. Jefferson: McFarland, 2004.

Marrone, Irene. Imagenes del Mundo Historico: Identidades y Representacions En El Noticiero y El Documental En El Cine Mudo Argentino. Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblios, 2003.

Sendrós, Paraná. “La Celestini hizo un solo film.” Ámbito Financiero (4 April 1988): n.p.

Zago, Manrique, ed. Cine Argentino: Crónica de 100 años. Buenos Aires: Manrique Zago Ediciones, 1997.