When discussing Julia Crawford Ivers, film historians primarily emphasize two things: her remarkably introverted personality, and her role as principle scenarist for William Desmond Taylor (Foster 1995, 199; Lowe 2005, 286). However, her 1930 obituaries assign Ivers a more independent and influential position, with the New York Times describing her as a “scenario writer, director and production supervisor” (19) and the Los Angeles Times making the inflated and incorrect claim that Ivers was “the second woman to become a film director in Hollywood” (A20). Given that a number of other women directed motion pictures before Ivers had her first opportunity in 1915, this last claim may say more about the way early Hollywood publicity machines operated than about the nature of her film industry work between 1913 and 1923.

One might speculate that Ivers, given her tendency to avoid publicity, became an inadvertent public figure after she found herself briefly considered as a suspect in Taylor’s infamous, and still officially unsolved, 1922 murder. Perhaps it was this suspicion, combined with her extreme shyness and the almost total unavailability of photographic images of her, that led to the name “Lady of the Shadows” that has become attached to Ivers. The few glimpses we have of Julia Crawford Ivers come from the obligatory publicity she did as a studio employee, reviews of the films she wrote and directed, and her aforementioned obituaries. At the time of her death, the Los Angeles Times reported that Ivers entered the film industry in 1913 when she began collaborating with Frank A. Garbutt. At that time, Garbutt was working with the Oliver Morosco Photoplay Company, which produced films for release under then-distribution company Paramount Pictures Corporation. In 1920, during a Moving Picture World interview with A. H. Giebler, Ivers admitted that she was flexible during her early years working in the industry, having “done almost everything around a studio but sweep the floor” (951). After six years at Morosco, Ivers began the next stage of her career in the production arm of the powerful Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount organization (A20). At what she calls “the Lasky plant,” Ivers wrote, directed, and held a variety of other positions “from film cutter and editor to superintendent of the plant” (Giebler 951).

While under contract to the Famous Players-Lasky Company from 1919 to 1922, during which time it became vertically integrated as Paramount Pictures Corporation, Ivers worked closely with William Desmond Taylor, a collaboration that resulted in the production of approximately twenty films and ended abruptly with Taylor’s 1922 murder. After Taylor’s death, Lasky appointed Ivers as one of the studio’s four supervising directors, making her, according to the Los Angeles Times in 1923, “the only woman to have directed from the Lasky lot” (III 33). This phrasing, “from the Lasky lot,” allows for a seemingly contradictory fact: another woman, the renowned Lois Weber, was hired the year before Ivers and proceeded to direct some films for Famous Players-Lasky. While Weber was clearly under contract to the same studio between 1918 and 1921, she may not necessarily have shot her films on the lot. Karen Mahar suggests that Weber’s contract was not renewed because she failed to fully adapt to the “modern” morality mandated by Lasky’s box-office formula (Mahar 2006, 148). We thus need to know more about the specific circumstances that might explain why Ivers was attributed such an unusual position on the Lasky lot, particularly given what is known about the paternalism of the company. For example, some women who worked with producer-director Cecil B. DeMille (scenarist Jeanie Macpherson, secretary Gladys Rosson, editor Anne Bauchens) were retained as long as they were loyal.

The Famous Players-Lasky writing department, under William deMille, was similarly tight-knight and patriarchal in those years, though women scenarists such as Beulah Marie Dix, Marion Fairfax, and Clara Beranger enjoyed relatively long tenures. An interview conducted by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin while Ivers was shooting The White Flower (1923), the last film she would direct, reveals both her fierce independence as a writer and director and her willingness to defer to all-powerful producer Jesse Lasky. “I wrote the story… with a genuine love and affection for the islands, and will produce it in the same way. No ‘roughneck’ of a director will have a chance to squeeze the fragrance out of the plot, for I am going to direct the action myself,” she says. However, Ivers follows up this confident statement by dutifully crediting her powers to Jesse Lasky’s largess: “Mr. Lasky permitted me to select my own cast and to choose my technical force, camera man, art director and all. I am in full charge and I have every confidence in my company” (Ivers 1992).

While it may seem surprising that Julia Crawford Ivers was the only woman to whom Jesse Lasky assigned a directing project once Weber ’s contract expired, one must keep in mind that Ivers arrived at Famous-Players Lasky with both directing and screenwriting experience. In 1915, Ivers wrote her first screenplay for the still surviving short The Rug Maker’s Daughter (1915), a Morosco Photoplay Company production that starred the celebrated dancer Maud Allan in her debut film appearance. In that same year, Ivers also directed her first film, the dramatic short, The Majesty of the Law (1915), an extant film that, like many of Ivers’s later films, was well received by critics. We know from the review in the Atlanta Constitution that The Majesty of the Law, praised for its appeal to “all classes,” tells the story of a Virginia judge who sternly hands down severe sentences while in court only to later help the families of those he condemns (B4). The Washington Post gave another one of Ivers’s extant films, A Son of Erin (1916), a similarly positive review, describing the tale of a peasant who moves to America to discover the “promised land” as a “screen story of unusual beauty, full of action and appealing in its beautifully romantic charm” (4). Although directorial credit for The Call of the Cumberlands (1916) is often ascribed to Frank Lloyd, AFI and FIAF both attribute Ivers with director credits for The Call of the Cumberlands, another extant film, which compares well with other, better-known later feud films exquisitely shot on location in Appalachia, such as Stark Love (1927), directed by D. W. Griffith’s cameraman, Karl Brown, and Dorothy Davenport Reid’s last production, Linda (1929). Also in 1916, Ivers adapted The Heart of Paula, which was also shot on location, this time in Pedro Blanco, Mexico. Most remarkably, Pallas Pictures, which shared a studio with Morosco at the time, promoted The Heart of Paula as a film that offered motion picture theatre managers a unique choice: they could screen either of the two distributed endings, which the New York Times described as either “tragic” or “happy.” Anthony Slide says that although William Desmond Taylor has most often received credit for directing The Heart of Paula, it is possible that this extant title was either codirected by Taylor and Ivers or by Ivers alone (Slide 1996, 127).

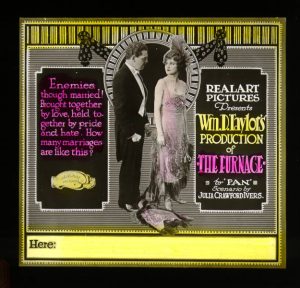

Lantern slide, The Furnace (1920), Julia Crawford Ivers (w). Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery, W. Ward Marsh collection

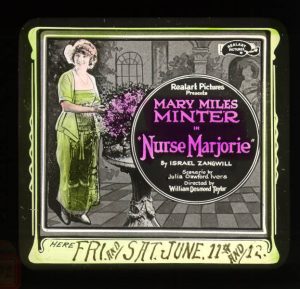

Lantern slide, Nurse Marjorie (1920), Julia Crawford Ivers (w). Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery, W. Ward Marsh collection

Ivers, like other writer-directors such as Marguerite Bertsch and Ruth Ann Baldwin, also commented on the relationship between writing and directing. In 1920, she is quoted as saying that “The writer is only a helper… and sometimes very poor help. More stories have been spoiled than made by writers who tried to put them in picture form, and if many of the writers who are yelping for credit on the screen should be debited with the lack of imagination and lack of vision they display, they would have no more to say” (Giebler 951). In a 1923 Boston Daily Globe interview Ivers also contemplated how film production quality might be improved if directors and writers were to switch roles: “If all scenario writers could direct at least one picture… and all directors could write just one scenario, motion pictures would benefit tremendously” (11).

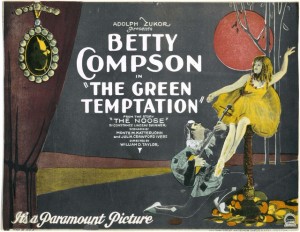

In her ten-year career, Julia Crawford Ivers was credited with writing more than forty original screenplays and adaptations, and she was praised in reviews for her technical knowledge as well as her writing abilities. In reviewing Widow by Proxy (1919), the Atlanta Constitution lauded Ivers as “a scenarist of rare talent and wide experience” and described her as “an expert on screen technique” (D5). Screen credits reveal that she effectively worked as a producer at Pallas Pictures on at least two films including the five-reel Lost in Transit (1917). In total, Ivers likely directed four films during her career, a fact substantiated by Ivers in an interview published in the Morning Telegraph in 1917, six years before she directed her final film, The White Flower (V6). While directing The White Flower, shot on location in Honolulu over the course of six weeks, Ivers shot scenes from inside volcanic craters, pineapple plantations, and lush undergrowth. Betty Compson described Ivers’s physical directing prowess to the Washington Post, explaining that “Mrs. Ivers has proved time and again that she yields the palm to no mere man megaphone manipulator. She took chances and smiled…. We worked in rain and wind, thunder and lightning, storm and stress” (59). Like so much of Ivers’s writing and directing work, The White Flower was critically well-received; yet it proved to be her swan song. Shortly after finishing the film, the Los Angeles Times reported that Ivers “resigned her long association with the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation as supervising director” in order to pursue work as a free-lance writer (III 33). As with so many of these news reports from the 1920s announcing that the studio writer would “free-lance,” we have to wonder if this was the optimistic spin put on the more likely event that a studio contract was not renewed. In Ivers’s case, her failing health also prevented her from resuming her job as a studio scenarist, and she completed only two more writing projects before her death, after which her record of achievement in the industry became almost completely obscured.