Who Worked at What and When

This project began just after the centennial celebration of the motion picture, during a distinct turn to historiography in the field, and in the light of intriguing new evidence that continues to surface. We set out to prove that women were not just screen actresses in the silent era, in the two decades before the advent of synchronized sound motion pictures. Carrying over the impetus from the 1970s, we looked first for evidence that they had worked as directors but in the process we found that they had been not just directors. Women’s participation in the first two decades was both deeper and wider than previously thought. In addition to costume designer, as one might expect, the researchers on this project found, as one might not expect, camera operators as well as exhibitors (theatre owner and/or theatre manager). In her groundbreaking business history of women filmmakers in the silent era, Karen Mahar adds the colorist and the film joiner as well as the supervisor and the executive producer to this list.1 At first, many jobs were not necessarily gender-typed, she says. In the first decade, however, some departments became exclusively organized along gender lines, with editing or joining being the most visibly gendered work.

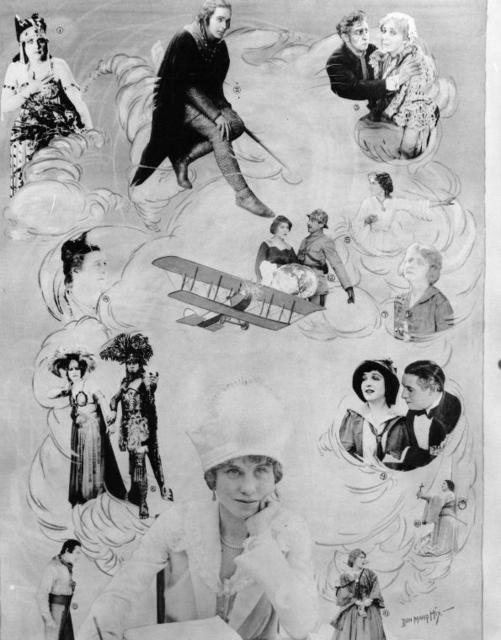

Yet the most comprehensive overview of the industry, Business Woman, in 1923 listed twenty-nine different jobs that women held (in addition to actress), including that of typist, stenographer, secretary to the stars and executive secretary, telephone operator, hairdresser, seamstress, costume designer, milliner, reader, script girl, scenarist, cutter, film retoucher, film splicer, laboratory worker, set designer and set dresser, librarian, artist, title writer, publicity writer, plasterer molder, casting director, musician, film editor, department manager, director, and producer.2

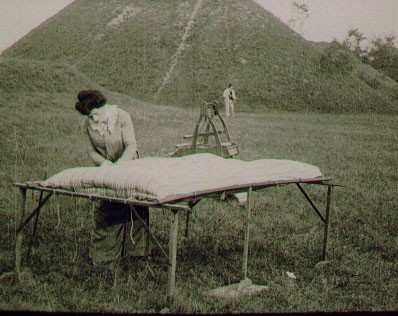

![Essanay Film Mfg Co. Laboratory personnel, Chicago. AMPAS]](https://wfpp.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/How_Women_Worked_fig1b_WFP-COM011.jpg)

Essanay Film Mfg Co. Laboratory personnel, Chicago. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

When Were Motion Pictures Silent?

Clare West with design sketch. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Scholars date the advent of motion pictures from the first public Lumière Company cinématographe exhibition in Paris, France, on December 28, 1895, and in the United States, from the Edison Company’s New York City kinetoscope premiere on April 4, 1896.3 Yet, as Mahar has pointed out, the first years were defined by competition over equipment patents, the realm of men (2006, 25). The best way of explaining early opportunities for women is to first think of the growth spurt represented by the US nickelodeon boom, 1906–1909, which meant increased demand for short, one-reel films to screen at these storefront theatres. The influx of the women we are tracking begins around 1907—the year Gene Gauntier wrote a scenario at the Kalem Company based on Ben Hur, Florence Lawrence took a role in the Edison Company’s Daniel Boone; or, Pioneer Days in America, and Alice Guy Blaché, married three days, set sail for New York from Paris, as each recalls in a memoir (Gauntier Oct. 1928, 184; Lawrence 1914, 40; Slide, 1986a, 60-61).

MGM publicity photo, Agnes Christine Johnston. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Although 1927–1928 marks the official transition to sound years in the US, many of the titles we list were issued in both silent and sound versions.4 Titles after 1928 are included for other reasons. First, experimental and documentary work expand the definition of “silent film” because in the late 1920s and into the 1930s low-budget work was often shot silent with a nonsynchronous soundtrack added later, if at all. This allows us to consider, for instance, the extant 16mm print of the fourteen-minute A Journey to the Operations of the South American Gold Platinum Co., in Colombia South America (1937) made by anthropologist Kathleen Romoli, now in the Fundación Patrimonio Fílmico Colombiano in Bogotá. Or, we include the work of American experimental filmmaker Stella F. Simon, whose extant short Hände/Hands (1927–28) was restored by the Museum of Modern Art in 2001. Second, some women whose careers began in the silent era became more important in the sound era. Although she was a popular Mexican film actress in the silent era, Adela Sequeyro did not direct motion pictures until the 1930s, and two of the sound titles she directed are extant: Más allá de la muerte/Beyond Death (1935) and La mujer de nadie/Nobody’s Woman (1937).5 There was, however, no equivalent to Sequeyro in the United States.

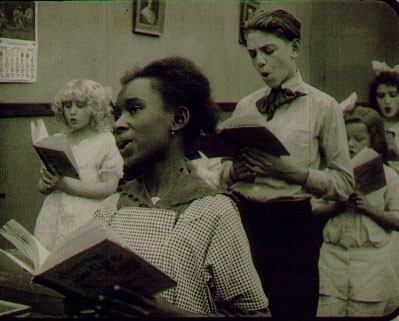

No silent era US motion picture actress began another career phase directing in the sound era, although some writers began before 1927 and continued to work productively into the sound era. Latin American industry examples contrast here with the US industry, where, the evidence shows, the ranks of women working as scenario writer, director, or producer thinned out by 1923 (Mahar 2006, ch. 2 and 6). It is commonly asserted that by 1925 the only woman still working as a Hollywood studio system director was the now-celebrated lesbian Dorothy Arzner. Less exclusive focus on directors, however, opens up this territory. Certainly Wanda Tuchock was another woman to stay employed in Hollywood, as Anthony Slide pointed out early (Slide 1996, 136). But her 1934 credit is not for director but for codirector on Finishing School for RKO with George Nichols, Jr. Her first silent era credit is as continuity writer on the Marion Davies star vehicle Show People (1923), the treatment for which was written by Agnes Christine Johnston while Johnston was on the staff at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. One of her next assignments at MGM was as scenario writer for the all-black cast classic Hallelujah (1929), directed by King Vidor, who also wrote the story. Like hundreds of other titles in the silent to sound transition years, Hallelujah was released in both sound and silent versions. Motion picture titles that straddle two technological moments, such as John S. Robertson’s The Single Standard (1929), written by Josephine Lovett, and Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star (1929), written by Sonya Levien and edited by Katharine Hilliker, call attention to the women whose careers began in the silent era and continued into the sound era: Lovett, Levien, Dorothy Yost, Sarah Y. Mason, Zoe Atkins, and Virginia Van Upp.

US Companies Outside Hollywood: 1915–1935

Dorothy Davenport Reid. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Leah Baird portrait. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

It is now well established that the phasing out of women paralleled the development of the motion picture business into the corporate studio system, in place by the mid-1920s. Yet the exceptions to the “over by 1925” rule are important.6 Many writers and most editors continued to work within the studio system, and a few companies started by Hollywood insiders remained, such as the Dorothy Davenport Reid company, Mrs. Wallace Reid Productions, operating from 1924 to 1929, and Leah Baird Productions, started with cool producer Arthur Beck, and lasting from 1921 to 1927.

Another economy is operative outside Hollywood, and thus we find women financing companies with family fortunes, organizational fund-raising, professional earnings, and divorce settlements. Some, like Madeline Brandeis, worked on the edge of Hollywood, where she started Madeline Brandeis Productions to produce educational shorts, operating between 1924 and 1929. A Midwesterner whose first film was produced in Chicago, Brandeis funded her first production with her settlement from the Omaha, Nebraska, Brandeis Dry Goods Store heir to whom she was married. A number of the short films Brandeis produced as part of the Children of All Lands series, distributed by Pathé, are extant.

Women such as Brandeis and Ruth Bryan Owen, who produced just a handful of films or even a single title, or whose involvement in film production took a secondary or, at best, equal place to other careers or to their roles as wives or mothers, might be understood as “mere dilettantes” or “amateurs.” The practice of overlooking them and their work is not restricted to standard histories of the silent motion picture era. The filmmakers themselves sometimes downplayed their own efforts as, for instance, Brandeis does when she describes her filmmaking as a “pastime” in an article tellingly entitled “Woman Makes Films for Fun.” This seemingly casual reference sheds some light on the conflicting imperatives that organized women’s abilities and desires to make motion pictures outside Hollywood, especially since, by the late 1920s, “outside” may have been the only place where they were able to continue working as filmmakers.

As a professional writer and lecturer, Osa Johnson continued to produce motion pictures after her husband’s 1935 death. The work of Frances Flaherty with her husband, Robert, considered the first American documentary maker, spans 1921–1932. Still photographer Nancy Naumburg made the 16mm titles Sheriffed (1934) and Taxi (1935) under the auspices of the Film and Photo League, the leftist New York collective. These initiatives have in common their nontheatrical distribution and their educational or political goals. While some ventures defined themselves as oppositionally outside Hollywood, others, such as the silent project The Flame of Mexico (1932), undertaken by a Washington DC diplomat’s wife, might be considered hybrid projects. Producer Juliet Barrett Rublee envisioned theatrical distribution for her tribute to the Mexican people, shot by a professional Hollywood crew. Thus, because The Flame of Mexico, a 35mm print of which surfaced in 2006, has such high production values, it is visually comparable to the Warner Brothers feature Juarez (1939) although the documentary sections remind us of Soviet avant-gardist Sergei Eisenstein’s footage for Que Viva Mexico (1932). Little research has been done on the earliest companies founded by women outside Hollywood, but Mahar mentions the Blaney-Spooner Feature Film Company in 1913, the Liberty Feature Film Company in 1914, and the company organized in 1914 by author and playwright Eleanor Gates, who was interested in adapting her own literary work for the screen (2006, 66).

Regional Producing and Directing: Before and Never Hollywood

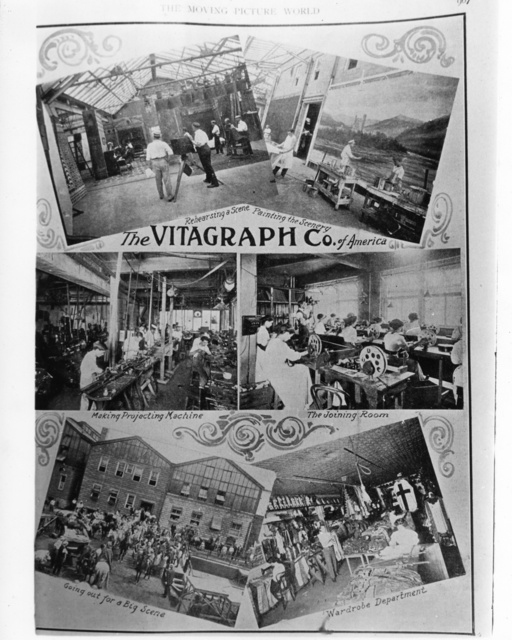

Women’s productions were fostered by the distance from bottom line-oriented major production centers, and the number of locations they used suggest that they discovered more possibilities in region-centered filmmaking. In the first decade, when film production sprouted around New York before the exodus to the West Coast, however, there was no major production center. Recent interest in filmmaking in New Jersey calls our attention to the earliest, the Solax Company, founded by Alice Guy Blaché in 1910 in Ft. Lee. When Helen Gardner left the New York City studios of the Vitagraph Company in 1911, she started Helen Gardner Picture Players in Tappan-on-Hudson, New York. In recent years, three of her feature films, Cleopatra (1912), Sister to Carmen (1913) and A Daughter of Pan (1913) have been restored and screened. Beta Breuil made short motion picture melodramas in Rhode Island in 1915 and 1916, four of which are extant: My Lady of the Lilacs, Violets, Daisies, and Wisteria. A strong African-American community in Kansas City, Kansas, constituted a viable audience for filmmakers Tressie Souders and Maria P. Williams in an era of race-segregated theaters.

Elizabeth B. Grimball filming The Lost Colony Film (1921). Courtesy of the University of North Carolina.

Regional history itself provided the impetus for another extant title, The Lost Colony (1921), commissioned by the state of North Carolina and directed by Elizabeth B. Grimball, recruited for the job from the New York theatre after she directed the “Lost Colony” pageant. Nell Shipman Productions (1921–1925) specialized in melodrama set in the North woods, taking dramatic advantage of the wildlife and rugged Priest Lake, Idaho, landscape. A representative sample of her shorts and features are extant, including the short White Water (1921), featuring an exquisitely photographed, tightly cross-cut river rescue scene that rivals D. W. Griffith’s Way Down East (1920). Lost, however, is the Ruth Bryan Owen production Once Upon a Time (1922) shot in Coconut Grove and Key Biscayne, Florida, which stood in for mythical Arabia in a production the director-producer cast with local amateur theatre actors.

Immigrant Outsiders and Outside Insiders

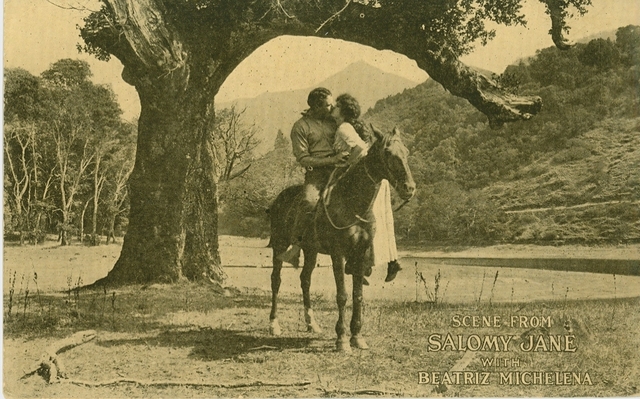

Mexican-American actress Beatriz Michelena headquartered her 1917–1919 company, Beatriz Michelena Features, in San Rafael, California, north of San Francisco. One of the titles the company produced, Just Squaw (1919), is held by the Library of Congress along with earlier Western genre films in which she starred produced by other companies. In Oakland, another part of the Bay Area, Marion E. Wong started the Mandarin Film Company and worked as actress, director, scenario writer, and producer of The Curse of the Quon Gwon (1917), recently discovered and restored. An intriguing reference leads us to wonder what kind of unit Japanese-American Tsuru Aoki, wife of actor-producer Sessue Hayakawa, was working in since she is cited as having in 1913 begun a “company of players.”7 But ethnicity and immigrant status don’t map perfectly along inside/outside lines, leading us to consider some as outside-insiders. Alison McMahan reminds us that Alice Guy Blaché was an immigrant from France and convincingly interprets her extant The Making of an American Citizen (1913) in these terms (2002, 142). But unlike so many others, Blaché did not arrive poor. When she disembarked in 1907 she held $50,000 worth of Gaumont stock that she would sell to start the Solax Company in 1910 (2002, 76).

It has long been established that the immigrant Jews who founded the US motion pictures studios, all of them male, began in dry goods and entertainment because these were the avenues open to them. The case of immigrant Jewish women is the reverse of that of the men who became moguls. For women, the two vehicles to entry were acting and writing, and these worked in different ways. Actresses of Asian or Hispanic descent or those who had migrated from Eastern Europe made difference, exotic-tinged, work for as opposed to against them. In changing her name from Miriam Edez Adelaida Leventon to Alla Nazimova, a young girl from a Russian Jewish immigrant family borrowed an exotic-ethnic effect, but later, as a mysterious lesbian and political radical, her persona acquired new associations. Nazimova Productions, 1917–1921, operating inside Metro and later linked to United Artists, was an artistically “outside” gamble in which she finally lost the money she had invested.

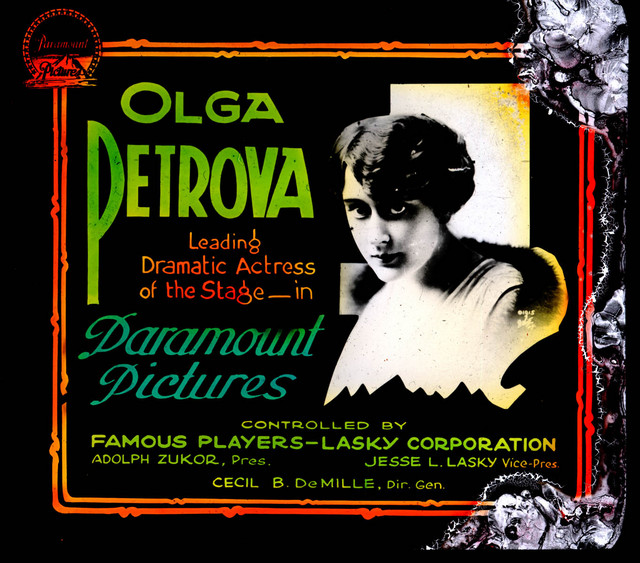

In the silent era, European exoticism was also faked. Welsh immigrant Muriel Harding styled herself as Polish countess Olga Petrova and as a move for artistic control, started Petrova Pictures Corporation in 1917, outside the studio system (McMahan 2002, 180). Valda Valkyrien, the Danish actress born in Reykjavik, Iceland, adopted the aristocratic persona of Mademoiselle Valkyrien to help her career when she immigrated to the US. She found work at the Thanhouser Company and later announced the Valda Valkyrien Production Company, although the evidence that the company produced any films has yet to be found.

Writers Sonya Levien and Anzia Yezierska were both from poor Jewish families that emigrated from Russia and settled on the Lower East Side of New York City. Yezierska, a reluctant transport to Hollywood, wrote about her bitter disillusionment in Cosmopolitan magazine in an article that begins, “I was very poor. And when I was poor, I hated the rich.”8 Her collection of short stories was produced by Goldwyn Pictures as Hungry Hearts (1922), 16mm prints of which are held in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles and the National Film and Television Archives in London. Frederica Sagor Maas, a second generation Jewish American born in the US in 1900, and blacklisted along with her husband in the 1950s, died January 5, 2012 at the age of 111.

One openly bisexual writer, Mary MacLane, became famous for her nonfiction The Story of Mary MacLane published in 1902 when she was only nineteen. She would sign a contract for several films with the Essanay Company, then in Chicago. Only one, however, was made, as Men Who Have Made Love to Me (1918), adapted by MacLane from her own short story and starring herself. The single film phenomenon is a pattern and marks another way insiders were outsiders. Temporary insiders were soon “outsiders,” and often on the verge of losing the precarious foothold they had established (sometimes as heads of companies or units within larger companies)—unless they achieved stardom as actresses or unless they were part of a powerful producing family. See “The Family System of Production.”

New York, California Before Hollywood, and Hollywood: 1907–1923

Women’s Work before It Was “Women’s Work”

Gene Gauntier and Kalem stock company in Florida. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

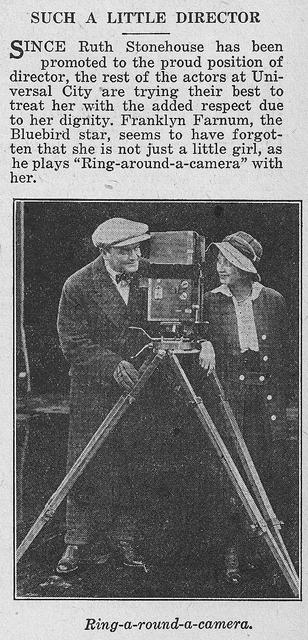

Work on the early motion picture set was relatively flexible, and in 1908 acting and directing were jobs like any other, on a par with lab work (Jacobs 1975, 59).9 Gene Gauntier describes the Kalem Company ensemble work from 1907 to 1912 as a scramble in which she did almost every job (Gauntier 1928). Actress Florence Turner even did the accounting at the Vitagraph Company studio in Brooklyn, New York, according to Stuart Blackton’s memoirs. At the Famous Players-Lasky Company in California, writer Beulah Marie Dix, newly arrived from the East Coast in 1916, stood in as an extra, learned about the camera, and took care of the lights (Brownlow 1968, 276). Many, like Bradley King, moved up from the lowest rung jobs as stenographers.10 As Mark Cooper describes the layout of the new Universal City lot completed in 1915 in Los Angeles, it created a kind of “laboratory for gender experiment” facilitated by “physical mobility” on the set in contrast to the New York office hierarchy (Cooper 2010, 63). These conditions produced the phenomenon we call the “Universal Women,” the largest concentration of women who worked as directors, sometimes also as writers, actresses, and producers, from 1916 to 1921: Ruth Ann Baldwin, Grace Cunard, Eugenie Magnus Ingleton, Cleo Madison, Ida May Park, Ruth Stonehouse, Lule Warrenton, Lois Weber, and Elsie Jane Wilson.

The Family System of Production

Boundaries between family and business were often blurred, best exemplified by the position of Gertrude Thanhouser, listed on articles of company incorporation as primary company stockholder,who acted, wrote, and served as a Thanhouser Film Company executive. Lloyd Lonergan, Edwin Thanhouser’s brother-in-law, wrote roughly nine hundred Thanhouser scenarios, and his sister Elizabeth Lonergan wrote for the Biograph and Kalem companies (Azlant 1997, 241).11 The DeMille dynasty that begins with mother Beatrice deMille is well known, but she is noted less for the scenarios she wrote for the Lasky company. The paternalism of Cecil B. DeMille and his brother William deMille (spelled differently) benefited writers Jeanie Macpherson, Olga Printzlau, Beulah Marie Dix,and Clara Beranger, as well as executive secretary Gladys Rosson and editor Anne Bauchens. All had long tenures beginning in the 1910s when what became Paramount Pictures was the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Players and then the Famous Players-Lasky Company.

MGM publicity portrait, Lorna Moon. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Scenario writer Lorna Moon’s illegitimate child with William deMille was adopted by his brother Cecil and his wife. Paula Blackton as director and actress was recruited along with her children in Vitagraph Company cofounder Stuart J. Blackton’s Brooklyn, New York, studio.Later in London, at Blackton Productions, Stuart Blackton gave daughter Marian Constance Blackton a valued place in production decisions as well as her start as a writer. Close working relationships fostered what could be called a “familial system of production,” which crossed and sometimes overrode the stages film historians have identified: the cameraman system, the director-unit system, and the central producer system of production.12

The motion picture set was also a newly gender-mixed workplace that fostered liaisons, and the married or romantically linked creative team was a norm. Going it alone was the exception. In the majority of these cases, however, the woman, not the man was “the ticket” since it was her stardom that commanded resources. See “The Star Name Company.” Men most often handled the money and business side in the partnership (Mahar 2006, 73). Historical evidence, however, challenges gender assumptions. We find men who were financially irresponsible (as in the case of the Victor Company started by Harry Solterer with Florence Lawrence) and women who demonstrated remarkable business acumen. Charlie Chaplin, for instance, recollects Mary Pickford at the meeting to form United Artists in 1919: “She knew all the nomenclature: the amortizations and the deferred stocks, etc. She understood all the articles of incorporation, the legal discrepancy on Page 7, Paragraph A, Article 27, and coolly referred to the overlap and contradiction in Paragraph D, Article 24.”13 he jury is still out, however, on the role that husband Herbert Blaché played in the dissolution of the Solax Company (1910–1922), which became Blaché American Features (1913–1914), effectively demoting Guy Blaché from company president to vice president (Mahar 2006, 73–76; McMahan 2002, 77, 121, 172–73).

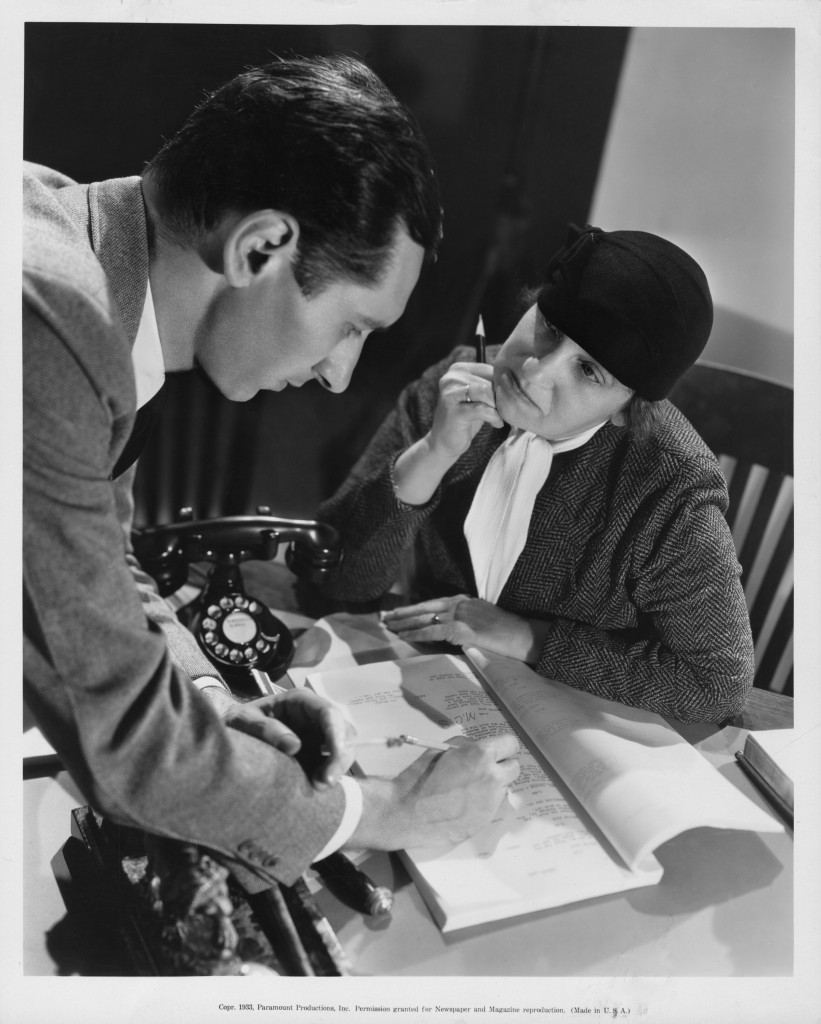

Josephine Lovett at desk. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library

The couple mode within the familial system was most likely a continuum, from the rocky liaisons undermined by infidelities to the collaborators-for-life, exemplified by teams whose contracts stipulated joint work, like writer-editor team Katharine Hilliker -H. H. Caldwell, who practiced job-sharing. See also “Women Scenario Editors”; “Scenario Writer to Screenwriter.” Mr. and Mrs. George Randolph Chester and Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew gave their marital status names to production companies although of a very different kind since the Chesters were writers who attempted to produce only once (The Son of Wallingford, 1921). The Drews developed a married couple comic persona for their “Mr. and Mrs. Drew” series, precursor, Mahar says, of the domestic screwball comedy. Further Mahar raises the delicate issue of who did the work, suggesting that it was Mrs., not Mr. Drew who produced and directed the series within the Vitagraph Company (2006, 117).14 Anthony Slide writes that Alice Terry was known to have stepped in to finish directing scenes for husband Rex Ingram (1996, 130–31). In a 1922 interview Louella Parsons conducted with husband of writer Josephine Lovett, director John S. Robertson, he describes their relationship as the “work and play together” ideal personified by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and Mary Pickford (Parsons 1922, 4). The fan magazine publicity that espoused an equal partnership ideal, however, creates a smoke screen around the circumstances. As Shelley Stamp explains in her critical analysis of the domestic discourse around directing-producing team Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley, these relationships contained many ingredients.15 Countering the image of perfect partnership, however, is the evidence that Weber was the dynamo (Mahar 2006, 91–92). In many cases the separation of female from male partner in a creative team may be an artificial after-the-fact operation. Unofficial information that conflicts with published motion picture credits is indicated in the “Credit Report” note following the Archival Filmography and Not Extant Films at the end of each profile. The following list of working partnerships indicates that most were husband-wife relationships.

Working Partnerships

Husband-Wife Teams

Mary Jobe Akeley — Carl Jobe Akeley

*Leah Baird (actress-writer) — Arthur F. Beck (producer)

* Bessie Barriscale (actress-producer) — Howard Hickman (actor-director)

Cora Beach (writer) — Walter Shumway (writer)

Dwinelle Benthall (writer) — Rufus McGosh (writer)

Clara Beranger (writer) — William deMille (writer)

Ouida Bergère (writer) — George Fitzmaurice (director)

Pauline Bush — William Dowlan

*Lillian Chester (writer-producer) — George Randolph Chester (writer-producer)

Frances Hubbard Flaherty — Robert Flaherty

*Gene Gauntier (actress-writer-director-producer) — Sydney Olcott (actor-director-producer)

*Gene Gauntier (actress-writer-director-producer) — Jack C. Clarke (actor-director)

Eloyce Gist (editor) — James Gist (director-writer-producer)

*Ethel Grandin (actress) — Ray Smallwood (cinematographer-director)

*Alice Guy Blaché (director-producer) — Herbert Blaché (director-producer)

Ella Hall – Robert Z. Leonard

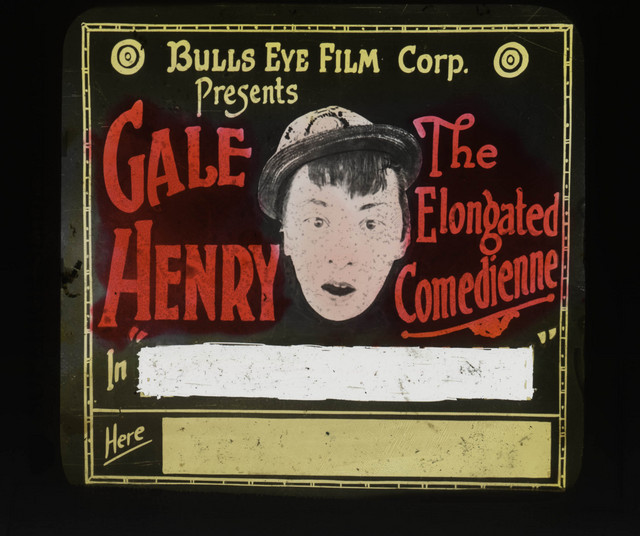

*Gale Henry (comedienne-writer-producer) — Bruno J. Becker (producer)

Katharine Hilliker — H. H. Caldwell (editors, producers)

*Helen Holmes (actress) — J. P. McGowan (director)

Osa Johnson (producer, cinematographer) — Martin Johnson (producer, director)

Agnes Christine Johnston (writer) — Frank Mitchell Dazey (writer-director)

*Florence Lawrence (actress-producer) — Harry Salter (actor-producer)

*Marion Leonard (actress-producer) — Stanner E. V. Taylor (director)

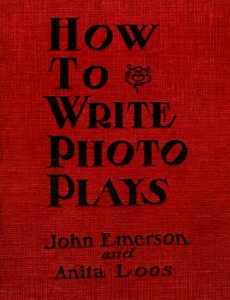

*Anita Loos (writer) — John Emerson (director-writer)

Hope Loring (writer) — Louis “Buddy” Lighton (writer-producer)

Josephine Lovett (writer) — John S. Robertson (director)

Sarah Y. Mason (writer) — Victor Heerman (writer)

*Lucille McVey (Mrs. Sidney Drew) (actress-director-producer) — Sidney Drew (actor-director-producer)

Bess Meredyth (writer) — Wilfred Lucas (actor-director)

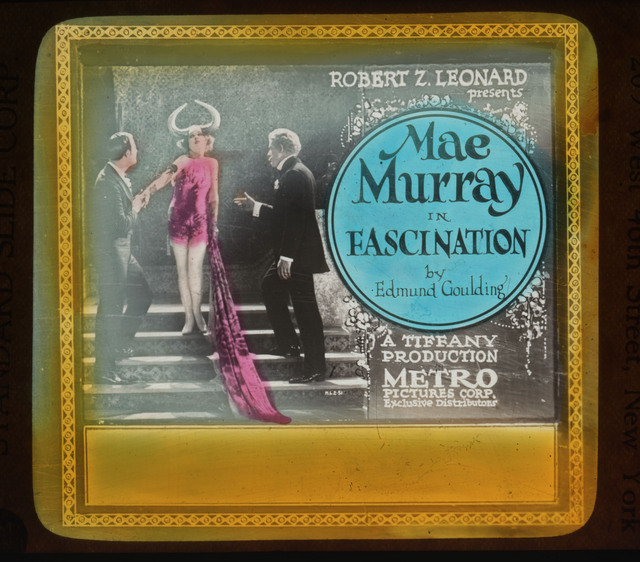

* Mae Murray (actress) — Robert Z. Leonard (director)

*Ida May Park (writer-director) — Joseph DeGrasse (director)

Dorothy Phillips (actress) — Allen Holubar (director-writer)

*Mary Pickford (actress-producer) with Douglas Fairbanks, D. W. Griffith, and Charles Chaplin

*Josephine Rector (writer) — Hal Angus (director)

*Lillian Case Russell (writer) — John Lowell (actor-writer)

Alice B. Russell (actress-producer) — Oscar Micheaux (director-producer)

Florence Ryerson (writer) — Colin Clements (writer)

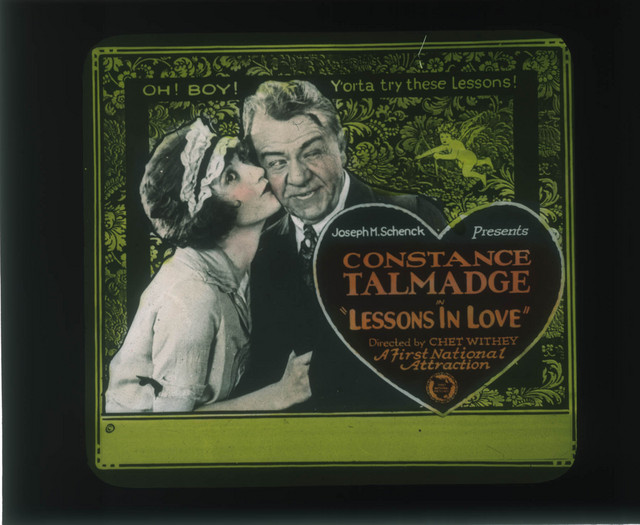

*Norma Talmadge (actress-producer) — Joseph M. Schneck (producer)

Alice Terry (actress) — Rex Ingram (director)

*Gertrude Thanhouser (actress-writer-producer) — Edwin Thanhouser (producer)

Rosemary Theby — Robert Henley

*Mrs. M. Webb (writer) — Miles M. Webb (producer)

*Lois Weber (actress-writer-director-producer) and Phillips Smalley (actor-producer)

*Madame E. Touissant Welcome — E. Touissant Welcome (co-producers)

*Kathlyn Williams (actress-producer) — Charles Eyton (producer)

*Maria P. Williams (writer-producer) — Jesse L. Williams (producer)

Elsie Jane Wilson (actress-director-writer) — Rupert Julian (director)

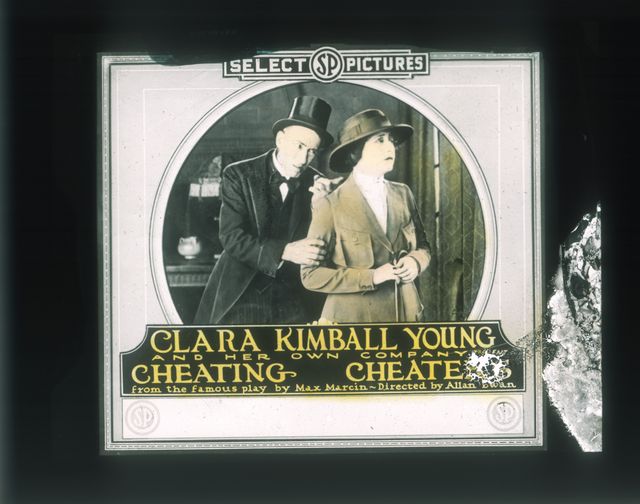

*Clara Kimball Young (actress-producer) — Harry Garson (director-producer)

Dorothy Yost (writer) — Dwight Cummings (writer)

Relationship Unknown

*Beatriz Michelena (actress-producer) and George Middleton (director)

Never-Married Couples

*Gale Henry (actress-producer) — Bruno J. Becker

*Helen Gardner (actress-producer) — Charles L. Gaskill (writer-director)

*Jane Murfin (writer) and Larry Trimble (actor-director-producer)

*Nell Shipman (actress-writer-director) — Bert Van Tuyle (director)

*Florence Turner (actress-director-producer) — Larry Trimble (actor-director-producer)

Fake Marriage

*Marie Dressler (actress-producer) — Jim Dalton (business manager)

Team, Not Romantic Couple

Sada Cowan (writer) — Howard Higgin (writer)

*Grace Cunard (actress-writer-director) — Francis Ford (actor-director)

*Gene Gauntier (actress-writer-director-producer) — Sydney Olcott (actor-director-producer)

Julia Crawford Ivers (writer) — William Desmond Taylor (director)

* Indicates started production company together. Note: See Women’s Production and Pre-Production Companies for dates and company names.

This list is not exhaustive and reflects research done prior to publication (2013)

Domestic Relations

Fan magazine writers liked to point out exceptions to the rule that creative teams were husband-wife teams. Motion Picture Magazine had to tell readers that Francis Ford was not married to Grace Cunard, but that he had a “real wife,” as they put it—Mrs Elsie Van Name Ford—who wrote the stories he used in the independent productions he made after leaving Universal Pictures.16 But where the studios specialized in publicizing spouses, thus advertising the heterosexuality of creative personnel, the industry community was divided about children and upheld what might be called a “double standard” of domestic disclosure. In 1916, Photoplay, typically obtuse on the subject, stated the obvious—that in the screen industry, actresses were always “Miss” whether married or not. But the editors take to task those women who keep their children secret, referring to them as “queer movie mothers ashamed of their babies.”17 Researchers on this project confirm that there are relatively few contemporary references to children born to and raised by women working primarily as screen actresses. Writer Frances Marion in a 1958 interview later explained the practice of camouflaging not only pregnancy but child-rearing when she confirmed that “Husbands and babies had to be hidden in the background.” Marion thinks that Gloria Swanson was the first to dare to say that she was married and also that she was a mother.18 Still in 1958 terminated pregnancies and illegitimate children could not be mentioned and researchers have had to wait decades for “reveal all” autobiographies in order to begin studying the work-to-domestic relations ratio in these women’s emotional lives.19 The moral code, however, may have been more strict for actresses than for female scenario writers. A rare photograph of mother Sarah Y. Mason, who worked with Victor Heerman as a husband-wife writing team, plays on her double role dexterity. Also unusual is this image of parents and children not featured as a performing family. The photo of Dorothy Davenport Reid with husband Wally Reid and their children Betty and Wallace Reid, Jr., circulated as a publicity image after he tragically died as a consequence of morphine addiction in 1923 and she returned to work, visibly the suffering widow. Sometimes atypical units were featured in fan magazine articles as when the home life of Cleo Madison was filled in with a mother and the invalid sister she supported. A woman was single because she was divorced (as Madison) or in between husbands or lovers. She was single even if, especially if, she was in an established lesbian relationship like Dorothy Arzner and her partner Marion Morgan or writer Zoe Akins and actress Jobyna Howland. Researching these alliances requires us to look behind references to a woman’s “single” status or see the terms “companion” or “roommate” for the code words they really are. We learn to be sensitive to the references to serial relationships that point to gay and lesbian liaisons as, for instance, Anita Loos ’s mention in a 1938 letter to H. L. Mencken that Zoe Akins had a “new lover” (qtd. in Holliday 1995, 233).

What we want to know most of all is what went on inside the homes of Hollywood celebrities and their friends. Zoe Akins was noted for the parties she threw at her home at 6350 Franklin Avenue in Hollywood for guests such as Dorothy Arzner, director George Cukor, writer Somerset Maugham, and actress Billie Burke (once allied with Arzner). From a Cecil Beaton article in Vogue in 1931 we know that “the house shared by the Misses Zoe Akins and Jobyna Howland” was “full of the most exquisite objects, full of charming and literary personalities” (qtd. in Mann 2001, 74).

Mabel Normand with chauffeur. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

We can infer from the great number of exterior photographs of motion picture celebrity homes that fan magazines tantalized readers with these images. Photoplay made the connection between these exteriors and the domestic comfort of their interiors in a 1917 article. The publication of images of the homes of Marie Doro, Gladys Brockwell, Louise Glaum, Ruth Stonehouse, Mary Pickford, Bessie Barriscale, Tsuru Aoki, and Kathlyn Williams suggests that mansions and adorable bungalows were good publicity for their owners. Strangely, Photoplay dares to address the means by which these players were able to acquire the capital to buy luxurious homes, tying their earnings to the enthusiasm of fans in a reference to the “net proceeds of homage.”20 But fan magazine writers had to strain to make a connection between what looks like real estate advertising and the lives of favorites. To score a photograph of Nazimova standing outside her mansion in jodhpurs would have been a coup. Then again, the number of willing subjects reminds us of how many not only understood the motion picture advertising value of signs of wealth but also its diversionary function. Mabel Normand outside her home sitting in her chauffeur-driven limousine belies a life of scandal and chronic illness. The diversion of the home also promoted diversion itself as an ideal. Here, the aura of work-as-play enveloped writers as well as players. Highly paid Famous Players-Lasky scenario writer Beulah Marie Dix walking her dachshund in front of her luxurious Southern California stucco residence reassures readers that her work is not exactly work. One angle on the story about Dix (and a rationale for taking interior publicity photographs), might have been that she worked from home.

Whose Work: Credits and Uncredited Work

Male-female working partnerships raise the difficult question as to whether the female contribution was submerged or whether joint authorship had its own assumed standard. Collaboration was the norm in the first decade at the start of which all creative workers were uncredited. One early film historian would thus describe the development of the motion picture industry as moving from anonymous production to screen credit (Jacobs 1975, 121).21 Attribution, if there was any, was unofficial, as Eileen Bowser explains in her study of the 1907–1915 years. Credits were not advertised in trade papers until in 1911 when the Edison Company published relatively complete cast lists (actors, directors, authors) and around the same time a few companies placed cast credits in titles, as Bowser determined from examining surviving motion picture film prints (Bowser 1990, 118).22 The combination of early anonymity and the very conditions of collaboration in the case of creative couples can create some confusion. Following the Archival Filmography and Not Extant Films, contradictory records and retrospective corrections are referenced in the “Credit Report” note.

Director and/or Producer

The focus here on women directors is both a misnomer and a key. In her important introduction to the “Cinema as a Job” section of The Red Velvet Seat, Antonia Lant explains that, given the “fluctuation” of opportunities in this period, directing, the plumb job, is a “most sensitive indicator of job range” (562). That the trade press, fan magazines, and the women most involved also saw directing as a key indicator is borne out in what Lant terms the “debate” over the question of the female director. She finds that these public discussions kept alive the terms of the debates around women’s suffrage, terms that were echoed in the 1970s (568).23 One finds among the figures quoted here the position that women were not suited to direct (Lillian Gish, Alice Guy Blaché) as well as the position that women were uniquely suited to it (Clara Beranger, Lois Weber, June Mathis). Ida May Park espoused both positions at different times in her career (Denton 49; Park 335–37). Many have noted the apparent inconsistency between public statements and the responsibilities these women undertook, most notably directing, producing, and executive managing, and Lant reminds us to consider the historical moment in which these statements are made (562). Here we also emphasize the conditions under which women worked. For instance, the months in which Lillian Gish, in the absence of D. W. Griffith, acted as supervisor of the Mamaroneck, New York, studio, she also directed her only motion picture, the feature Remodelling Her Husband (1920). Richard Koszarski provides the information that the studio, the former Flagler estate, was under construction and the cameraman Gish relied upon was suffering from World War I shell shock (2008, 17).

The findings here indicate no perfect correspondence between directing or writing jobs and identification with feminism or even espousal of equality for women. A very few associated themselves with feminism (Sonya Levien, Adela Rogers St. Johns), and at least one first associated with and then disassociated herself from feminism (Olga Petrova). Surprisingly, one of the most unqualified statements on behalf of women’s equality comes in 1912 from Beatrice deMille, the mother of motion picture impresarios William and Cecil B. DeMille, and in her own right a powerful New York theatrical agent who became a scenario writer: “This is the woman’s age. I think it has come to stay. Every relation between the sexes has changed. Hereafter, no woman is going to get married without feeling that she is getting as much as she gives. This may sound… crude… but it expresses pretty clearly what I mean…. This theme ‘women’s equality’ lives very close to my heart.”24 We could take up this theme and claim the first two decades as a “Golden Age of Women in Cinema.” Or, we can approach the question with more caution since the evidence is not all in as yet.

The competing evidence of women’s own writings as well as other sources from the 1910s and 1920s point to an evolution of job terminology as well as of the jobs themselves. While Alice Guy Blaché would be called a “directrice,” she was also clearly a producer, beginning in France at the Gaumont Company and continuing in the US, where she was producer as well as president of the Solax Company, as Alison McMahan tells us in her definitive study (McMahan 2001, chs. 3 and 4). Consider as well the power of retrospective recollection in memoirs and later interviews to make claims as well as to issue disclaimers. Charlie Chaplin notoriously credited himself as director on Keystone Company films on which Mabel Normand was assigned as director.25 Terminology in addition to roles themselves was in flux, so there was no standard way of referring to a woman who stage-directed a one-reel motion picture production as Jeanie Macpherson, who in 1916 was referred to as a “directress,” did (Martin 95).

Jeanie Macpherson, The Tarantula (1913). Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Often male as well as female directors were “picturizers,” and, ambiguously, just “producers.” Even the Universal Weekly, the company house organ, through the 1910s uses “director” and “producer” almost synonymously, Cooper finds. To complicate matters, a unit within a larger company (effectively a company within a company), might be headed by a “producer” or a “producing director,” he further explains (Cooper 2010, 40). Here, we have credited women who were involved in production companies as “producers” as a means of adding a facet to a career, understanding, however, that there is more variance under the term “producer” than under “director.” Karen Mahar has used the term “actor-producer” picked up below. See “The Star Name Company.”

Not only were “producing” and “directing” terminologically interchangeable, but the distinction between directing, acting, and writing was not always clear. As an actress who in 1917 would start a company, Petrova Pictures Corporation, Olga Petrova recalled in her memoir, Butter With My Bread, that in the “infancy” of the industry, written scenarios were conceived as well as abandoned by both director and actors. Here she describes the creative exertions of “Mr. K.,” the director who rewrites by enacting, and the ravishment of the heroine, an expectant mother, in a scene from an unnamed domestic melodrama:

Although the scenarios were always read to me for approval, it was quite possible for a director to change them out of all recognition as we went along. Members of the supporting cast rarely knew more of the piece than the episodes in which they appeared. These scenes were outlined by the director, but for the most part he left the dialogue to the imagination of the performer. As it was considered very amusing by some artists to try to break one another up, the dialogue, during the actual photographing of the scene, had very often nothing in common with the action. This was disconcerting enough, but the habit of a certain director of counting aloud between bellows through a megaphone, to “hop it up” or “ease it up,” was more disconcerting still. Very early in Mr. K’s direction I found the only way to combat this was to stop in the scene and beg his pardon for not having understood. This of course wasted considerable film, for we had to start all over again. Usually after the first day or so of the filming of a story, Mr. K would discard the script and outline the scenes from memory. Sometimes he improved on the original, sometimes he didn’t, but his manner of telling was always picturesque. I remember very well one scene going something like this: “You’re in your living room, working on some baby clothes. You register great joy at the coming of the little stranger. Your husband’s away and you’re thinking about a surprise he’s going to get when you give him the glad news. There’s a knock at the door… the mail man… a letter from your husband. Perhaps it’s to say he’s coming back sooner than you expected. You press it to your heart. You break the seal. You read it once. You can’t believe your eyes. You read it again. He ain’t coming back. He ain’t never coming back. He’s gone off with your best friend. Here we’ll count five for you to faint. You drop all of a heap, the letter clutched in your hand. We count five again. You come to. You look around you. ‘Where am I?’ you register. You drag yourself on your hands and knees to the couch, and you throw yourself face down on… shoulders… sobs. Your whole life’s ruined. Nothing matters no more. Suddenly you hear a sound. The latch clicks. You look up. The Baron enters. With a lascivious smile on his lips he comes toward you. “‘So… he’s gone,’ says the Baron. ‘What did I tell you?’ he says. ‘Didn’t I say he was a no-good bum? Didn’t I tell you he was playing around with this dame? And you wouldn’t believe me, would you? You sacrificing yourself, doing your own housework, wearing mangy old duds, never going anywheres, just so he could build up his business. Now you see where he’s brought you.’ “‘Don’t, don’t. Have mercy. Have pity,’ you says. Then he says, ‘Now maybe you’ll listen to me. Maybe you’ll come to have a little sense. There’s lots left to live for. It’s a great life if you don’t weaken. You can have beautiful clothes. You can have maids to wait on you. You can have a fine house, not a dump like you got now. You can have diamonds and yachts, and travel. I’ll settle a hundred thousand dollars on you. All you’ve got to do is say the word.’ “Now he starts coming nearer. He gets his arms around you. You try to push him off of you. You struggle to your feet. But he’s still grabbing you by the waist. Your hair gets all loose and falls over your shoulders. Your kimono tears open at the throat. You try to pull it together, but no use. As you struggle and struggle it gets ripped all the way down. Still you fight on, but you’re no match for the Baron. At last he overpowers you. You fall exhausted…. Cut.” By this time Mr. K had worked himself into a very interesting state of emotion. He was, as was once said of Mr. Gladstone, “carried away by his own exuberance of his own verbosity.” I felt I could never do any sort of justice to the scene after his description of it. This conviction was further strengthened by the fact that the “Baron” was a short, thin, pale weed of an individual whom I could very easily have taken over my knee and given a good trouncing (Petrova 1942, 260–61).

Petrova’s description of Mr. K’s direction contrasts with her experience of working under the direction of Alice Guy Blaché, who was more open to actor’s contributions:

In the first scene, as in all succeeding ones, Madame Blaché outlined vocally what each episode was with action, words appropriate to the situation. If the first or second rehearsal pleased her, even though a player might intentionally or not alter her instructions, as long as they did not hurt the scene, even possibly improve it, she would allow this to pass. If not she would rehearse and rehearse until they did before calling camera. When she had cause to correct a player, she would do this courteously, and in my case, which was more than often, she might resort to her native tongue. This gentle gesture touched me deeply, softened any embarrassment I might feel. After all the scenes were set for the day had been shot, the close-ups followed…. These concluded, Madama looked, and was, tired. But during rehearsals and shooting she never lost her dignity or poise. She wore a silken glove, but she would have been perfectly capable of using a mailed fist if she considered it necessary (Petrova, “A Remembrance,” in Slide 1986a, 102–103).

Women’s Producing Companies: “Her Own” or Not Her Own?

Second Wave feminists often quoted modernist writer Virginia Woolf’s advice that if she is to write “A woman must have money and a room of her own.” The case of women who helped to start companies in the motion picture business, however, is not exactly parallel. Even while the attempt to gain more creative freedom may have explained the fact that there were more total independent companies with women’s names than men’s names, many factors intervened in the complicated process of industrial motion picture production. First, the concept of “Her-Own-Company” that Karen Mahar has retrieved for us is somewhat ironic in that it comes from a 1916 Photoplay editorial that refers to a “‘her-own-company’ epidemic,” by which the magazine means that from its point of view there were entirely too many companies started by star actresses following the example of Mary Pickford and Clara Kimball Young. Second, Mahar divides the phenomenon of women’s companies including the star name company into two “waves” or movements, with Photoplay’s imagined “epidemic” applying to the second. Thus: Movement 1: 1911–1915 and Movement 2: 1916–1923.26 Third, and perhaps most important, Mahar cautions that the star actress’s name is no guarantee of the amount of power she wielded in the enterprise, particularly since the majority of these businesses were male-female partnerships (2006, 62). In the absence of company business records, most telling are documents such as distributor George Kleine’s deposition in the 1915 legal proceedings against Grandin Films involving Ethel Grandin and her husband Ray Smallwood. Clearly we cannot tell from the company name alone about either business arrangements or creative dynamics, and the term “company” may refer to either an independent legal entity or to a creative team, which might include an actress, a director, a writer, a camera operator, and others assigned to work together—again, a company within a larger company.

The Star Name Company

Marion Leonard portrait. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Film studies scholarship on the US star system has been particularly strong on the commodification of the star actress as a modern form of public personhood.27 In this scholarship, female stars such as Marlene Dietrich have been understood as taking symbolic control of their on-screen images.28 Until recently, however, the idea that women in the silent era attempted to take control of their images by legal and economic means was an anomaly. Now, however, a second wave of star studies will need to consider the silent era “actor-producer” as well as the “actor-writer” as we imagine the many who also wrote their own scenarios. The question once posed of how to interpret image and narrative as favoring a woman’s point of view now becomes one of how actresses first used scenario writing as well as performance to turn the tables on convention. If, after they achieved fame, they chafed against creative constraints, how did they manage to break away and start up one business after another? In this regard, Marion Leonard may be as historically significant as Florence Lawrence, so often cited as the first motion picture star. At the Biography Company, Leonard is thought to have written and/or directed the extant one-reel Lucky Jim (1909), in which Jim is not so lucky because he has married a physically abusive shrew. In 1911, Leonard and her director husband, Stanner E. V. Taylor, left Biograph to set up Gem Motion Picture Company, the first of two companies they would start, capitalizing on Leonard’s popularity because they could.

The star name company in which the star’s name may or may not have been used in the title was either a company or a “unit” within a larger studio or company, thus more of what might be called a “dependent company” as opposed to an independent company. For example, actor-director Sydney Olcott and Gene Gauntier worked together as the Olcott-Gauntier unit within the Kalem Company, 1910–1912. After Olcott and Gauntier, along with her husband Jack C. Clark left the Kalem Company, they operated as Gene Gauntier Feature Players Company, an independent company, between 1912 and around 1915. The differences between being a totally “indie” company or a semi-independent company that was part of a larger studio or company boiled down to the sources of capital, the advantage of self-contained departments (editing, publicity, legal), and, most significant in terms of public exhibition, commercial distribution that might be undertaken by the larger company that had its own distribution channels. For some, as was the case with the Kalem Company, distribution to exhibiting theatres was guaranteed by the Motion Picture Patents Company cartel. Later, beginning in 1915, larger companies began to buy up their own theatres, a means of insuring exhibition. Independent companies, however, had to contract with separate distributing or releasing companies, sometimes at their peril. Producer-writer-director Nell Shipman recalled in her autobiography that she had been tricked into taking too low a percentage on the distribution deal that she struck with American Releasing Corporation for The Grub-Stake (1922). As a consequence, she lost money when she should have been the one to profit (114–115).

In the US, companies formed pre-World War I, 1910–1915, were coincident with the foundation of the first moving picture businesses, the transition from one- and two-reel to multireel films (from shorts to features). Post-World War I company foundation corresponded with the American rise to world film industry dominance made easier by weakened French, German, Italian, and British motion picture businesses.29 Here is how social and economic conditions in Mahar’s two high points for US star name companies favored initiatives differently:

Wave 1: 1911–1915: Actresses left Biograph, Kalem, and Vitagraph, the companies that had promoted them to stardom. Marion Leonard, the second “Biograph Girl,” started Gem (1911) and later the Mar-Leon Corporation (1913); the Vitagraph star who gave her name to Helen Gardner Picture Players (1911–12) produced features; and Ethel Grandin, with Raymond C. Smallwood, formed Grandin Films (1914–1915) and later Smallwood Film Corporation. With Sydney Olcott, Gene Gauntier started the Gene Gauntier Feature Players Company (1912–1915), and the first “Biograph Girl” Florence Lawrence, with Harry Solter, her husband, formed the Victor Film Company (1912–1914). Here, as counter to the myth of available US capital, it is notable that “Vitagraph Girl” Florence Turner, frustrated in her attempt to raise financing in the United States, found it in the United Kingdom. With Larry Trimble she set up Turner Films, which operated in Britain, 1913–16, but was curtailed finally by World War I.30 Renting the Hepworth Studios in London, the two produced, among other titles, the extant one-reel comedy in which they compete in a funny face-making contest, Daisy Doodad’s Dial (1914). One might have thought that US women, replacing men drafted into the armed forces in World War I, would thus get a foot in the door in the film industry. While women did not replace men in the US, they did in the German film industry, where even an American, a circus performer from Watseka, Illinois, seized the opportunity. She hyphenated her first and last names as the Fern-Andra Company, begun in 1915.

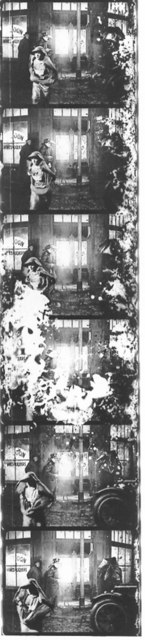

Frame enlargement, Florence Turner, Daisy Doodad’s Dial (Turner Films, 1914). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Frame enlargement, Florence Turner, Daisy Doodad’s Dial (Turner Films, 1914). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Wave 2: 1916–1923: Let us consider this second high point from the industry perspective of “too many women.” Recall that in December 1916, Photoplay editors identified what they thought was a disturbing development in Hollywood. They count six “producing companies headed by women” either already “grinding out plays” or in early stages of formation (“Close-up,” 63-64). Yet Photoplay makes two exceptions— companies started by Mary Pickford and Clara Kimball Young. Early historical accounts of the US film industry written by Terry Ramsaye and Benjamin Hampton also feature Pickford and Young, although not the many others that the magazine blames for causing an “epidemic” (63). The star name company in the Ramsaye and Hampton versions is seen as part of the story of how US motion pictures became big business. Female stardom is not an opportunity for players to gain creative control. Rather, star recognition is an asset turned to the advantage of the great moguls. In Hampton, Lewis J. Selznick’s idea for a company named for actress Clara Kimball Young, an offshoot of his World Film Corporation, is a “daring” means of financing production through franchises sold as advances against film rentals. Buyers were wealthy investors, including mail order entrepreneur Arthur Spiegel and theatrical agent William O. Brady (135). Terry Ramsaye’s narration of the protracted 1916 deal-making between Pickford and Adolph Zukor gives somewhat more weight to Pickford, who emerges as a canny negotiator. But in Ramsaye’s telling it is Zukor’s Pickford coup that cinches the Famous Players-Lasky purchase of distributor Paramount Pictures Corporation. In time, the birth of mammoth producer-distributor Paramount Pictures would dwarf the actress’s contractual triumphs—the Mary Pickford—named studio and the separate distribution company for her films, Artcraft Pictures Corporation (741–751). See “Motion Picture Distribution: 1910–1923.”

Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Mary Pickford, Charles Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, founders of United Artists, 1919. Private Collection.

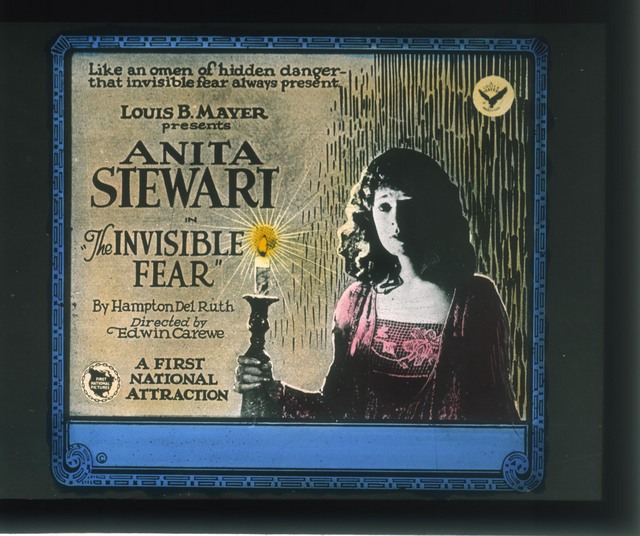

Recent reevaluation of the careers of Clara Kimball Young (Mahar 2006, 164–166) and Mary Pickford (Schmidt 2003, 59–81) see the struggle for creative control more complexly and open the door to understanding the way actress-producers threatened the forces of corporatization in the 1916–1923 moment. The 1919 formation of United Artists as the only production-distribution company run by powerful actors and directors, however, has been just the most visible sign of actor rebellion against studio management.31 But Pickford’s victories were not lost on the other actors and actresses who sought script control, guaranteed distribution, studio space, and a share of the profits in the short moment when stars could take advantage of their bargaining power. Some of these would form Bessie Barriscale Productions, Leah Baird Productions, Anita Stewart Productions, Helen Holmes Production Corporation, and Texas Guinan Productions. Less well known are the attempts of actresses Ruth Stonehouse and Lule Warrenton at producing and directing after they left Universal Pictures.

Alla Nazimova, Camille (1921). Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

The risks of independent financing were great, as the case of actress Alla Nazimova illustrates. Nazimova Productions was set up by Lewis J. Selznick within Metro Pictures, where the extant art deco classic Camille (1921), written by June Mathis and designed by Natacha Rambova, was produced. But when in 1922 Nazimova became a United Artists partner, producing the more experimental Salome (1923) with her own capital, she lost everything and was never able to finance another film.32 See “US Companies Outside Hollywood: 1915–1935.” Less dramatic losses were sustained by Margery Wilson Productions on That Something (1921) and Vera McCord on Good-Bad Wife (1921), although these companies never made another film after the first venture.

Lule Warrenton portrait. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Highlighted in this overview are only a fraction of cases. There were many more than six “her own” production companies in 1916 and more by 1922, and forty is a better estimate for this second moment if one counts cases in which women started more than one company. See “Women’s Production and Preproduction Companies.” But the new industry attitude toward women in the business is starkly apparent in the Photoplay editorial. Because US fan magazines had been beating the drum enthusiastically for women as producers and directors, the editorial’s negative tone seems an abrupt reversal. Photoplay editors are worried that these start-ups signal a throw-back to a less rigidly stratified and controlled mode of production. Aligning itself with new principles of management applied to the creative process, the magazine sees women’s independent companies as the “bane of the industry,” because, harkening back to an earlier stage, they threaten to “drag film-making back to its days of solitary, suspicious feudal inefficiency” (63–64). Here, in one of the very few articulations of the threat star name companies must have represented to the hierarchization of the studio, we glean insight into the perception of women. They were not team players (“solitary”) and not organized to maximize profit (“inefficient”). Terry Ramsaye, writing the first comprehensive history under the auspices of Photoplay in 1926, would sum up the pro-management terms: “Every element of the creative side of the industry is being brought under central manufacturing control” (833). Finally, in a reversal of their earlier support for the star system, new studio heads Carl Laemmle (Universal) and Adolph Zukor began to identify star actors as a problem. Cecil B. DeMille and Jesse Lasky at Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount retaliated against actresses and actors’ active resistance to centralization and “efficiency” by announcing in 1922 a war on the star system.33

Another reversal was more devastating to women’s companies. First National Exhibitors’ Circuit, which had been the salvation of independent companies as a distributing consortium, became itself a producing company, Associated First National Pictures. See “Motion Picture Distribution: 1910–1923.” Beginning in 1917, First National had provided production funds for motion pictures planned by Olga Petrova, Anita Stewart, Mary Pickford, Constance Talmadge, Norma Talmadge, Anita Loos, Katharine MacDonald, Mildred Harris-Chaplin, Hope Hampton, and Marguerite Clark.33

Under centralized control in Burbank, California, in 1922, those actresses who had signed with First National lost the advantages of independence. A case study in these changes is Corinne Griffith Productions, whose 1923 First National contract spelled out the new terms. She left the weakening Vitagraph Company at a high point in her career, expecting to make all of the creative decisions for the new Corinne Griffith Productions. Her contract, the prototype of the seven-year contract of the studio system, gave her no control over budget, casting, or script, and no profit-sharing. In 1928, First National was bought by Warner Brothers. Griffith was not an isolated example, considering, for one, Tiffany Productions and Mae Murray, who lost control of her company to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer between 1922 and 1924.35

Women’s Production and Preproduction Companies

Anita Stewart Productions — 1918–1922, with Louis B. Mayer (producer)

Beatriz Michelena Features — 1917–1919, with George Middleton (director/producer)

Bessie Barriscale Feature Company — 1917, with Howard Hickman (actor/director)

B.B. Features — 1918–1920, Bessie Barriscale with Howard Hickman

Blaney-Spooner Feature Film Company — 1913, Cecil Spooner with Charles E. Blaney (producer)

Clara Kimball Young Film Corporation — 1916–1917, with Lewis J. Selznick (producer)

C.K.Y. Film Corporation — 1917–1919, Clara Kimball Young with Adolph Zukor (producer)

Equity Pictures Corporation — 1919-1924, Clara Kimball Young with Harry Garson (director)

Constance Talmadge Film Company — 1917, with Joseph M. Schneck (producer)

Eleanor Gates Photoplay Company — 1914 (announced)

Eve Unsell Photoplay Staff, Inc. — 1921

Fanchon Royer Productions — 1928

Fay Tincher Productions — 1918–1919

Flora Finch Company — 1916-1917

Flora Finch Film Frolics Pictures Corporation — 1920

Florence Turner Productions, Ltd. — 1913–1916, with Larry Trimball (actor-director)

Frieder Film Corporation — 1917, Lule Warrenton

Gem Motion Picture Company — 1911, Marion Leonard with Stanner E. V. Taylor (writer-director)

Monopol Film Company – 1912, Marion Leonard with Stanner E. V. Taylor (writer-director)

Mar-Leon Company — 1913, Marion Leonard with E. V. Stanner E.V. Taylor (writer-director)

Gene Gauntier Feature Players — 1912–1915, with Sydney Olcott (director) and Jack Clark (actor) (1915)

Olcott-Gauntier Unit — Kalem Co. — 1910–12, Gene Gauntier with Sydney Olcott (actor-director)

Gloria Swanson Productions — 1926–1928

Gloria Films — 1928, Gloria Swanson and Joseph P. Kennedy (producer)

Grace Davison Productions — 1918

Grace S. Haskins — 1923

Smallwood Film Corporation – 1913, Ethel Grandin with Ray C. Smallwood (director), Arthur Smallwood (brother)

Grandin Films — 1913–1915, Ethel Grandin with Raymond C. Smallwood (director)

Helen Gardner Picture Players — 1912–1914, with Charles L. Gaskill (director)

Helen Gardner Picture Players — 1918

Helen Gibson Productions — 1920

Helen Holmes Production Corporation — 1919

Signal Film Corporation — 1915, Helen Holmes with J. P. McGowan (producer)

S.L.K. Serial Corporation — 1919, Helen Holmes with J. P. McGowan (producer)

Helen Keller Film Corporation — 1919

Ida May Park Productions — 1920, with Joseph DeGrasse (director)

Leah Baird Productions, Inc. — 1921–1927, with Arthur Beck (writer)

Liberty Feature Film Company — 1915, Sallie Lindblom

Lois Weber Productions — 1917–1921, with Phillips Smalley (actor-director)

Rex — 1912–1914, Lois Weber with Phillips Smalley

Louise Lovely Productions — 1917

Lowell Film Productions — 1925, Lillian Case Russell with John Lowell [John L. Russell] (writer)

Mabel Normand Feature Film Company — 1916, with Mack Sennett (producer)

Madeline Brandeis Productions — 1924–1929

Mandarin Film Company — 1917, Marion E. Wong

Marie Dressler Motion Picture Corporation — 1916–1917, with Jim Dalton

Marion Davies Film Corporation — 1918–1920

Cosmopolitan Productions — 1918-1923, Marion Davies with William Randolph Hearst

Margery Wilson Productions — 1921

Marion Fairfax Productions — 1921–1922

Mary Miles Minter — 1928 (announced)

Micheaux Film Company — Alice B. Russell (actress) with Oscar Micheaux (director)

Model Comedy Company — 1918–1919, Gale Henry with Bruno J. Becker (director)

Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew Comedies — 1917–1919, with Sidney Drew (actor)

Mrs. Sidney Drew Comedies — 1920

Mrs. Wallace Reid Productions — 1924–1929

Nazimova Productions — 1917–1922, Alla Nazimova

Nell Shipman Productions, Inc. — 1921–1925, with Bert Van Tuyle (director)

Norma Talmadge Film Company — 1917, with Joseph M. Schneck (producer)

Pacific Motion Picture Company — 1914, Josephine Rector with Hal Angus (actor)

Petrova Pictures Corporation — 1917, Olga Petrova

Pickford Film Corporation —1916–1919, Mary Pickford

United Artists — est. 1919, Mary Pickford with Charles Chaplin, D. W. Griffith, and Douglas Fairbanks

Ruth Roland Serials, Inc. — 1919

Solax Company — 1910–1922, Alice Guy Blaché (writer-director) with Herbert Blaché (director)

Blaché American Features —1913, Alice Guy Blaché with Herbert Blaché (director)

Texas Guinan Productions — 1920–1921

Tiffany Productions — 1921–1924, Mae Murray with Robert Z. Leonard (director)

Trimball-Murfin Productions — 1922, Jane Murfin and Larry Trimball

Unique Film Company — 1915, Mrs. M. Webb (writer) with Miles M. Webb (producer)

Valda Valkyrien Production Company (announced)

Vera McCord Productions — 1921

Victor Films — 1912–1914, Florence Lawrence with Harry Solter (actor)

Touissant Motion Picture Exchange —Madame E. Touissant Welcome with E. Touissant Welcome (co-producers)

The Western Film Producing Company and Booking Exchange—Maria P. Williams (writer-producer – Jesse L. Williams (producer)

Motion Picture Distribution: 1910–1923

Independent companies were formed when economic factors favored their chances of securing commercial distribution. The fortunes of women who worked as producers and directors were tied to the corporate struggles to control the domestic motion picture market, the wars to line up production with exhibition and distribution. One approach to the industry battles is thus to see two uncertain periods as windows of opportunity for independent autonomous production companies. In the 1912–1915 period, the MPPC monopoly was breaking up and new production and distribution companies challenged their dominance.36 Then, around 1916–1923 “indie” companies responded strategically to motion picture mogul Adolph Zukor’s attempt to monopolize. He tried to sew up distribution then consolidated production, insuring exhibition outlets for his films by buying up motion picture theatres as the new entity Paramount Pictures. Independent production companies and the consortiums that arranged distribution are only part of the story, however, since in these years both company security as well as “her own” company independence produced opportunity for women.

Frame enlargement, Le Matelas alcolique/The Drunken Mattress (Alice Guy Blaché, Gaumont, 1906). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Considering Alice Guy Blaché as a director-writer-producer helps us to understand the transition from the MPPC power to independent uncertainty and the rule of distribution. She founded the Solax Company in 1910 with every expectation of profitability, perhaps because film distribution was then guaranteed through the French Gaumont company’s arrangements with MPPC licensee George Kleine. Indicative of the close connection between the two companies, the extant short Gaumont comedy Le Matelas alcolique (1906) was recut and distributed by Solax as The Drunken Mattress. But when in 1912 Gaumont broke off with Kleine, Solax released films in the US through the consortium of independents that opposed the MPPC, the short-lived Motion Picture Distributing and Sales Company (which became the Sales Company).37 While the Sales Company distribution could be seen as having offered a solution that saved the company, in the long run, without the wider distribution the MPPC offered, Solax was not economically viable (McMahan 2002, 70, 75–77). After the break-up of the MPPC, exhibitors formed consortiums that, through merger or transformation into new entities, came and went. The short-lived distributor Alco Film Corporation, another exhibitors’ consortium, handled distribution for such companies as the Manhattan-based Popular Plays and Players. In the years after the demise of Solax, Alice Guy Blaché, working for Popular Plays and Players,would write and direct The Tigress (1914) with Olga Petrova, whom she helped to make into a motion picture star (McMahan 2002, 1980). After Alco became Metro Pictures Corporation in 1915, the new company distributed The Empress (1917), one of the few extant feature-length Alice Guy Blaché titles, currently not restored.

This connection between economic viability and guaranteed distribution applies as well to all of the companies that belonged to the Motion Picture Patents Company cartel, effective between 1908 and 1912: Edison, Vitagraph, Kalem, Essanay, Biograph, Selig, Pathé, and Lubin. The one- and two-reel short films these women wrote and performed in were distributed through a tightly controlled system of exchanges and licensed theatres. In leaving the MPPC-member Vitagraph Company in 1911 and setting up Helen Gardner Picture Players to produce Cleopatra (1912), Helen Gardner calculated that her best option would be the “road show” approach to print distribution (Bowser 1990, 192).

Later, Lois Weber and other “Universal Women” were guaranteed distribution through Universal Film Manufacturing Company, founded in 1912 by Carl Laemmle, one of the challengers of the MPPC monopoly. Whether her films were made as Rex, Bosworth, or Lois Weber Productions, they were released through Universal, which, in 1916, had ambitions to distribute worldwide in India, Mexico, Australia, and Japan, where the Bluebird brand proved to be popular (Thompson 1985, 72).

The second window of opportunity for independents, which corresponds with Mahar’s 1916–1923 wave of star name companies, was far more important for women’s companies, which benefited from the exhibition-distribution wars. The First National Exhibitors’ Circuit was formed in 1917 by an exhibitors’ consortium in the revolt against Zukor who was then forcing them to accept his prices for the most popular film product. First National, which grew to control perhaps as many as half of the theatres in the country by 1920, was an outlet that made independent companies financially viable for a few years.38 The consortium released the films of Norma and Constance Talmadge and Anita Stewart, among others, and the films of Trimble-Murfin Productions, the company writer Jane Murfin set up with her then-partner Larry Trimble.Setting up Petrova Pictures in 1917, Olga Petrova began with a First National Exhibitors’ Circuit contract for eight films although she finally made only a few of them. As Richard Koszarski explains the situation, Zukor threatened exhibitors because he controlled box-office draw stars, the most important of whom was Mary Pickford. He could, therefore, through the strong-arm tactic of what was called “block-booking,” force exhibitors to take inferior films in order to get Pickford films. First National’s move undercut Zukor’s strategy, which was an orchestrated takeover of his own distributor, Paramount, ousting Paramount founder W. W. Hodkinson and founding Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount (Koszarski 1990, 69–73). See “The Star Name Company.”

A few independent backers left standing outside First National and Paramount in 1922 sometimes helped to fund a single independent feature film. Photoplay’s 1923 article on twenty-two-year-old Grace Haskins features her as the “only other female producer” besides Lois Weber. For her first scenario Just Like a Woman, which she was to direct, Haskins received financial backing from the W. W. Hodkinson Corporation.39 Hodkinson, the founder and former president of Paramount Pictures when it had been a distribution company, was ousted from it in 1916 by Adolph Zukor. Anthony Slide tells us that with his new distribution company, Hodkinson handled the features of Bessie Barriscale. W. W. Hodkinson, however, went out of business in 1924 (Slide 1998, 237). This would explain the fate of Haskins’s film, although Leah Baird Productions, also helped by Hodkinson, stayed afloat until 1927. For a female producer outside Hollywood, the distribution options were limited, but at least they were not directly affected by the upheavals of the great motion picture profit centers. In Florida, once Ruth Bryan Owen had the support of the Federation of Women’s Clubs, she secured distribution through the Society of Visual Education for Once Upon a Time (1922). The history of the distribution company or consortium correlates with the existence of silent era 35mm film prints. If a producing company was ensured wide, even international distribution, more total prints were originally struck, and they were scattered throughout the world, sometimes ending up with foreign language intertitles.

One-Reel to Multireel Productions: The Feature Film

Florence Lawrence, in her “Growing Up with the Movies” recalls that the first production in which she appeared for the Edison Manufacturing Company, Daniel Boone; or, Pioneer Days in America (1907) sold outright for $150, which was 15 cents per foot (41). Within the next two years, however, the MPPC, of which Edison was the controlling member, put in place a system of film print rental as opposed to purchase, an attempt to control the 35mm print duplication considered a copyright violation. Thus we understand the 1909–1912 years of the MPPC as the period of rented shorts and the all-shorts mixed-genre exhibition program.

The one- or two-reel short film represented creative opportunity, and if there is a Golden Era of writing, producing, and directing for women in the US industry, it corresponded with the vogue in shorts. The very first women’s independent companies organized by Marion Leonard (Gem) and Ethel Grandin (Grandin Films) made shorts exclusively, and the prolific output of Alice Guy Blaché at the Solax Company, 1910–1912, was predominantly shorts. While it can be said that the MPPC actively sabotaged the independent producers and distributors, MPPC policy extended the heyday of the short film program even after it was clear that features were the future of the industry. On this point, Eileen Bowser makes the case that it was not the MPPC producer-members but the exhibitors that resisted changing the variety program over which they had more programming control. Although features were exhibited in 1910, they would have been distributed outside the exhibition system sewn up by the MPPC (1990, 192).

The bonus for women in the extended life span of the one-reel short is evident in the sheer number of credits for those who started at Vitagraph as an actress or a writer (Florence Turner, Marguerite Bertsch), Biograph (Mary Pickford ), or Kalem (Gene Gauntier). Most of the “Universal Women,” in addition to Lois Weber, Cleo Madison, Ruth Ann Baldwin, Ruth Stonehouse, and Ida May Park, practiced on the short films that Universal continued to make in the 1914–1916 period when other companies had made the transition to feature films. Most important, the popularity of comedy shorts made the careers of comediennes Alice Howell, Gale Henry, Marie Dressler, Flora Finch, and Fay Tincher. Short serials, which continued after the dramatic feature film, became the norm, providing work for Pearl White, Helen Holmes, Kathlyn Williams, and Grace Cunard. While it may be impossible to determine exactly how many female as opposed to male actors wrote, as we will see, what we can say is that many actresses also wrote stories. See “Scenario Writer to Screenwriter.”

But the sheer number of creative opportunities was eventually reversed when the more expensive multireel feature film became the standard, and it became more difficult to secure financing for larger production budgets. As Karen Mahar has pointed out, although feature films originally provided opportunity for independent companies outside the MPPC distribution and exhibition system, as the multireel feature presentation became the standard, the competitive strategy behind the feature film business involved eliminating small companies by raising the capital investment required (2006).

What Happened to Them?

One answer to this question of what happened to the women’s independent companies, largely gone by 1923, is that they were caught in a second corporate power-grab, a second monopoly thrust after the court-decreed end of the first.40 Many factors, however, were contributive: the 1918 flu epidemic and 1921 business recession meant that demand was down and consequently production slowed in these years. But while this confluence of factors explains changes in the industry in economic terms, another set of factors are needed to explain the difficulty women had finding employment or their decision to go into “retirement.” Women who specialized in scenario writing, however, were more apt to continue working for the new studios or to make a living freelancing. It seems likely that independent companies started by writers bucked the trend as with, for instance, Marion Fairfax Productions in 1922 and Lillian Case Russell with husband John Lowell’s Lowell Film Productions in 1925. In two other cases former actresses resumed work writing and producing. The best example is Dorothy Davenport Reid (1924–1929) but Leah Baird also did more writing than acting for Leah Baird Productions (1921–1927), started as part of a husband-wife team with producer Arthur Beck. After director William Desmond Taylor was murdered, his screenwriter Julia Crawford Ivers produced at least one film for Kathlyn Williams in 1917 and directed another, The White Flower (1923). See “US Companies Outside Hollywood: 1915–1935.”

Scenario Writer to Screenwriter