A delicate hand-colored photograph of Eva Nil’s face graces the cover of 50 Years of Film Archives, 1938-1988, edited by the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) in 1989. The caption inside the book reads: “Eva Nil, one of the most famous Brazilian stars of the 20’s. […] All films she has starred in are lost” (1). Nil’s stardom, carefully built up in the late 1920s, certainly remains alluring today. Her star persona, though, has somehow eclipsed other dimensions of her brief film career that deserve to be brought to the foreground, such as her activities as a producer, her keen sense of publicity, her technical skills and, in a broader sense, the professional attitude she adopted toward her career.

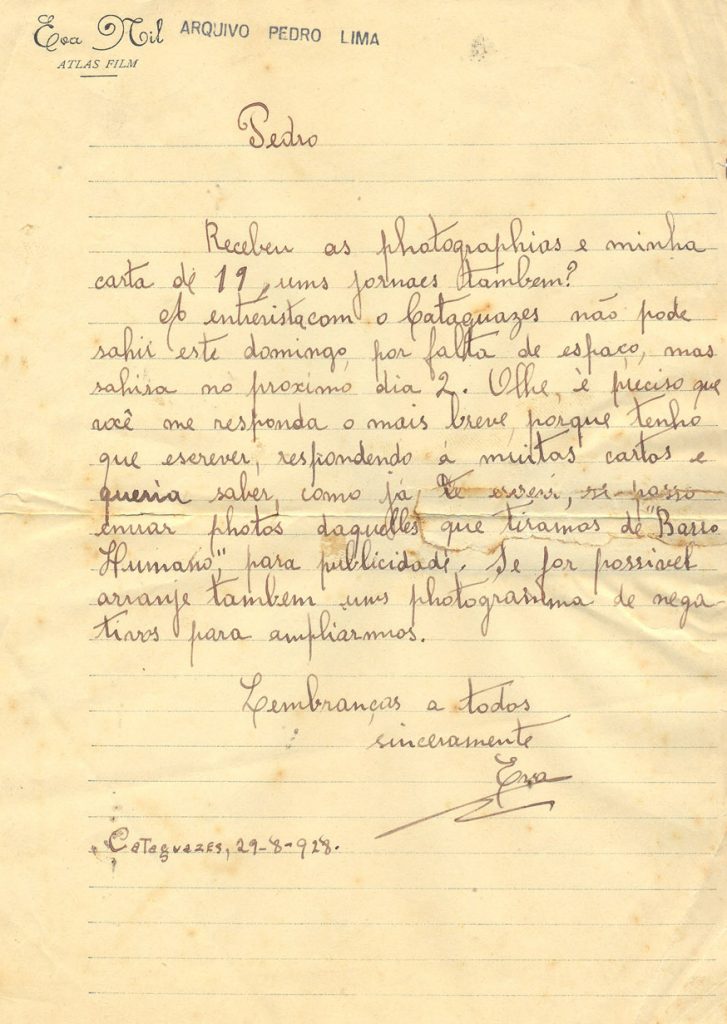

Letter from Eva Nil to Pedro Lima. Cataguases, 19 August 1928. Courtesy of Acervo Cinemateca Brasileira.

Mining archival sources proves fundamental to shedding light on Nil’s many activities. Her correspondence with journalist Pedro Lima—unfortunately divided between two archives, Cinemateca Brasileira, in São Paulo, and Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, in Rio—provides detailed information while also giving us access to Nil’s thoughts and opinions. Other letters, received from journalists and fans, are found at Cinemateca Brasileira in the artist’s personal archive, which also holds many press clippings and some movie theater programs. Rich material on Nil can also be found in newspapers and magazines, particularly in the Rio-based film magazine Cinearte. Engaged in a campaign to promote Brazilian cinema and to create its own star system, Cinearte journalists Adhemar Gonzaga and Pedro Lima gave Nil wide publicity through numerous articles and photographs. When Gonzaga directed his first feature, Barro humano/Human Clay (1929), which had Lima on the production team, Nil was even cast in a supporting role. That same year, however, when Nil was only twenty years old, she decided to withdraw from cinema, never working in film again (Ramos 514-516). Sadly, none of her films are preserved today, except for very short fragments of Barro humano and Senhorita Agora Mesmo/Miss Right Now (1927), the two-reel film she produced and starred in, which was directed by her father, Pedro Comello.

Nil’s connection with the early works of Humberto Mauro, who was to become one of the most acclaimed Brazilian film directors, along with the magnetism that her exquisite face and figure never fail to exert, has fueled a constant interest in her. Another decisive contribution to her long-lasting appeal was the essential book on Mauro’s early career, Humberto Mauro, Cataguases, Cinearte, published in 1974 by film historian Paulo Emilio Salles Gomes, which provides invaluable information on and insightful analysis of Nil’s films and personality.

Born in Egypt, where her father, the Italian Pedro Comello, served in the military and married Ida Tonetti, Eva Comello moved to Brazil with her family in 1914, settling in Cataguases, a town in Minas Gerais state. At the age of thirteen, Nil started helping her father in the photography studio he had opened in the early 1920s, an unusual job for a young woman in the eyes of the locals. There, she learned the craft and was in charge of the business during her father’s travels and after his death.

Nil’s first film role is usually considered to be the heroine kidnapped by the villain in Valadião, o cratera/Valadião, the Crater (1925), the first attempt at filmmaking by Humberto Mauro and Comello. In a letter to Cinearte journalist Pedro Lima, however, Nil claimed that she was filmed for the first time when working on the unfinished Três irmãos/Three Brothers, directed by her father in 1925 (Nil 1928). This information raises some questions, considering that Valadião, o cratera, shot with a Pathé-Baby 9.5mm camera, certainly preceded Três irmãos, a more professional project, in which an Ernemann 35mm camera was used. Perhaps Nil did not work on Valadião, o cratera, or she may have considered this amateur experience not worth reporting. Or it could be that declaring Três irmãos as her film debut was a way to reinforce her father’s importance in her career. A photograph published in Cinearte magazine a few years later shows Comello shooting a scene of Três irmãos. Interestingly, rather than being part of the scene, Nil stands at her father’s side, close to the camera, looking at the set, suggesting her concern with the technical aspects of production (Vidal 7).

In 1926, Nil starred in the feature Na primavera da vida/In the Spring of Life, directed by Mauro, with Comello operating the camera, and worked on Os mistérios de São Mateus/The Mysteries of São Mateus, another unfinished film directed by her father. She was to be the leading actress in Mauro’s following feature, Tesouro perdido/Lost Treasure (1927), but, after disagreements between her and the director, she refused to take part in it. This conflict with Mauro would last for years, which certainly explains Nil’s insistence in affirming, in her correspondence with Lima, that she was always directed by her father, even when he was credited only as the cameraman. The precise reasons she left Tesouro perdido remain unclear, but do seem to be related to a combination of financial, personal, and professional issues. Having already worked on the previous film, Nil did not accept being paid the same amount as the other unexperienced actors. Moreover, considering the story very uninteresting, she asked Mauro to make some changes; when he refused to do so, she quit the production (Nil 1928). Another reason may have been her refusal to be carried in the arms of an actor, in a scene that Mauro would not change (Schvarzman 154). This episode may reveal Nil’s conservative values, not unlike those of other young women of the time, as well as her professionalism. Right from the beginning of her career, she strove not only to make a creative contribution in shaping the roles according to her artistic—and moral—views, but also to be properly paid. As she had once declared to her mother, her goal was to earn a living working in cinema and photography (Estanislau 1).

Founding a production company seems to have been Nil’s way to pursue the professional standards she desired and to gain autonomy to develop more suitable projects. After Tesouro perdido, when Comello left Phebo Sul América, the production company he had founded with Mauro, he planned to produce non-fiction films (Gomes 179). Nonetheless, Nil convinced him to stay in fiction filmmaking and they both founded the production company Atlas-Film. In a 1927 letter to Lima, Comello reported that he decided to set up Atlas-Film “to satisfy my daughter’s aspirations,” adding that he also longed to make fiction films, “but the lack of capital is a big thing!” (Comello; emphasis in original).

Atlas-Film’s only production was the two-reel adventure film Senhorita Agora Mesmo, whose costs were limited to the purchase of film stock, according to a 1929 interview with Nil (“Ouvindo ‘estrelas’”). Although released at Cinema Glória, a first-run movie theater in downtown Rio, the film did not enjoy other commercial exhibitions, except for a couple of screenings in Cataguases and a nearby town, Miraí. Despite all the difficulties, which were far from unusual in Brazilian cinema at the time, owning a production company allowed Nil to develop a personal project in which she took on a variety of responsibilities. In Senhorita Agora Mesmo, not only did she play a strong female protagonist, but she also worked as a camera and laboratory assistant to her father alongside her activities as a producer and publicist.

In the film, Nil plays the fearless farm owner who, threatened by bandits, fights them to protect her mother and their property. The protagonist’s “energetic temper, always ready and determined” (“Senhorita Agora Mesmo”), earned her the nickname “Miss Right Now,” and mirrors the actress’s own personality. Instead of playing a romantic, fragile leading lady, Nil is an action heroine who, wearing masculine attire characteristic of the western genre, handles a gun and ties up the villains on her own—although in the end, imprisoned by the bandits, she is rescued by the young neighbor whose love advances she once rejected.

Modeled after the popular American serial queens from the 1910s, her character contradicted the dominant image of Nil built up by both the press and herself, through the pictures she regularly sent to journalists and fans. Nil was seen as “insinuating, gorgeous, gracious, natural in gestures, always with delicate expressions” (Folha Comercial), and as the “ethereal type of a Griffith ingénue” (IGO). For Atlas-Film’s follow-up film, Canção das ruas/Song of the Streets, which never came to fruition, she may have wanted to avoid a similar mismatch between her part and her star persona, announcing she would play “an interesting sentimental role” (Cinéfilo) this time.

While most references to Senhorita Agora Mesmo in the Brazilian press highlighted Nil as the film’s protagonist, sometimes also mentioning Atlas-Film as her production company, more detailed information on the technical work she performed was provided by the Portuguese film magazine Cine. Illustrated with a photograph of Nil with a dedication to the magazine, the piece, published in November 1928, presented information about her life and work, adding that in Senhorita Agora Mesmo she “held the megaphone and operated the camera’s hand crank. She also helped her father in film developing, cutting, editing and adapting the film according to her own artistic taste” (Cine). In Brazil, Nil’s camerawork was reported by Pedro Lima in Cinearte, who remarked that Pedro Comello was “substituted many times by the star of Cataguases [Nil], in the absence of anyone else who could replace him efficiently” (Lima [5 Oct. 1927]). Nil herself was the probable source of the information reported by both Cine and Cinearte, given her correspondence with Lima and the Portuguese journalist Mário D’Almeida, and it could be read as part of her effort to be regarded for other abilities, beyond acting.

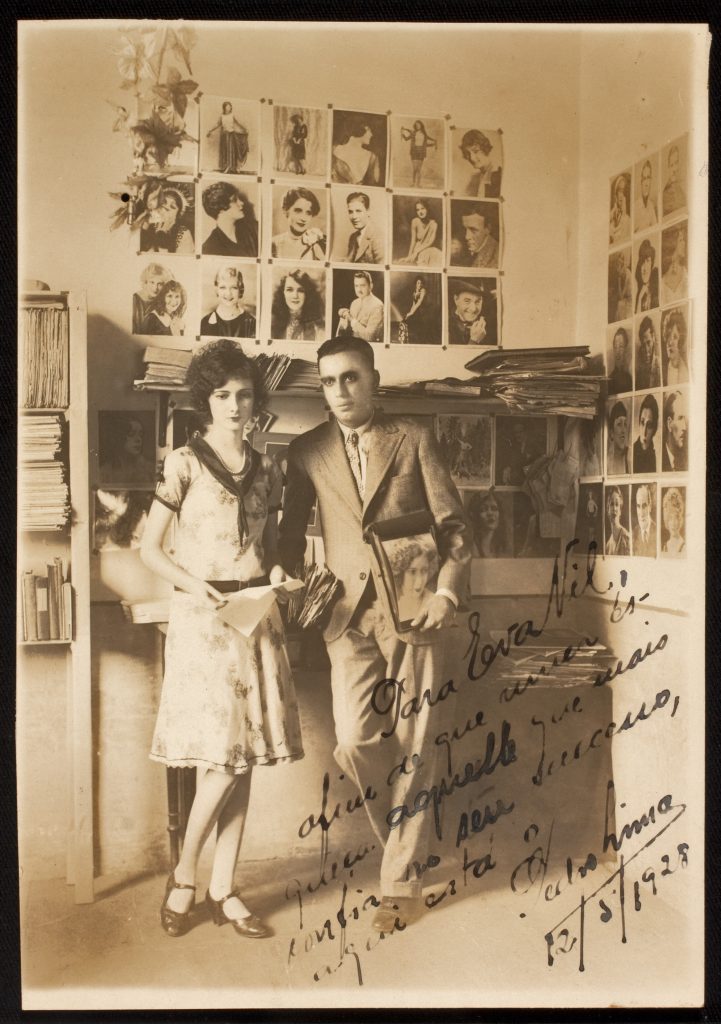

Eva Nil and Pedro Lima. Dedication: “For Eva Nil, so that you never forget the one who most trusts in your success, here is Pedro Lima 12/5/1928. Courtesy of Acervo Cinemateca Brasileira.

Lima also stressed Nil’s work in production, writing the following month that she was “the only independent female producer in our country, even though she is so young” (Lima [2 Nov. 1927]). Throughout their correspondence, it is clear how she was personally engaged in creating the production company Atlas-Film and in promoting Senhorita Agora Mesmo, in tandem with the promotion of her own star persona. Working in a photography studio gave Nil both the practical conditions and the technical skills to provide the press and her fans with a wealth of photographic material. Her portraits, some of them developed and printed herself, certainly benefited from her father’s basic knowledge of painting and visual arts.

Nil’s keen sense of publicity was soon spotted and praised by Cinearte as one of her most remarkable features. According to a brief note published in 1927, she was the only female artist who regularly sent them her most recent pictures; rarely a week passed without her writing to them. Likewise, her fans’ requests never went unanswered. The note, along with the three pictures published on the same page, is a striking example of Nil’s promotional abilities. Not only was she the only actress to congratulate the magazine on its first anniversary, but she also presented the publication “with each photo a treat”: one of them holds a dedication to Cinearte and, in the other two, Nil stands in a carefully arranged setting, flipping through the pages of Cinearte, while sitting next to a pile of what seems to be all the magazine’s previous issues (“Eva Nil”).

Nil’s professional attitude toward her career is also reflected in the way she faced her work in Barro humano, the only one of her films to enjoy distribution in several Brazilian states. In a letter to director Adhemar Gonzaga before shooting began, she expressed her excitement with the film. She looked forward to receiving his instructions, in order to study her part, which she wanted to be a sensation (Nil [2 Oct. 1927]). To Pedro Lima, she admitted that she desired a role “in which the work is not completely passive, but rather presents some challenges” (Nil [5 Sept. 1927]). Her critical concern about the role and her commitment to carefully prepare for it were not usual attitudes among Brazilian actresses and actors of the time. Nil’s work on the set was praised by Gonzaga in a letter to Humberto Mauro: “Eva Nil did very well. A sensation indeed” (Gonzaga).

The release of Barro humano in June 1929 to both public and critical acclaim encouraged Nil and her father to continue with their production company. A new project for Atlas-Film was announced, Canção das ruas, a feature film whose main scenes would be shot in Rio, and investments were made to remodel the studio and improve its technical resources. In a letter to Lima, Nil reported the acquisition of a new camera (“our Ernemann has already become a Debrie”) as well as professional printer and projection machines (Nil [29 June 1929]). Surprisingly, however, only a month after this letter, loaded with enthusiasm and promising news, Nil communicated to Lima her “complete withdrawal from working for the current national cinema” (Nil [20 Nov. 1929]). In stark contrast to her previous letter, Nil expressed her disappointment with Brazilian cinema. In doing so, she directly confronted Cinearte‘s discursive and promotional strategies, laying bare its false premises. “You say it [Brazilian cinema] does exist,” she wrote to Lima on November 20, 1929, “but you know very well it does not.” Her letter exposed “the awareness of an actress in the face of the economic and cultural limitations to which film activity in the country was imprisoned” (Melo 107). Although personal reasons cannot be discounted, the difficulties of making a living as a film professional in Cataguases certainly contributed a great deal to Nil’s decision. Nil and her father’s plan to pursue a film career in Rio, as Humberto Mauro would do soon afterwards, did not come to fruition. Nil stayed in Cataguases, working in the photographic studio until the 1970s, when it closed (Ramos 515).

See also: “Writing the History of Latin American Women Working in the Silent Film Industry”

The author would like to thank the Cinemateca Brasileira for kindly providing the photographs and the permission to use them and David Rushton for his collaboration with the translations.