Genevieve Harris was rather unique among women newspaper writers. Graduating from Eau Claire High School [Wisconsin] in 1908, she received a Bachelor of Arts (her major is unknown) from the University of Wisconsin in 1913 and did some graduate work at the Sorbonne in Paris. By late 1915, at the age of twenty-four, she was writing movie reviews for Motography (published in Chicago), a position she held until July 1918, just before the trade journal merged with Exhibitors Herald. Although several men also wrote reviews, Harris was the most constant, regular film critic. Her weekly reviews covered not only features but also serial episodes and short comedies, westerns, and other genres. She also conducted a few interviews with stars such as Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, and her last columns were notable for unusual interviews with local theater managers. This experience and her knowledge of the industry proved invaluable when, in August 1918, she took over writing daily movie reviews from Oma Moody Lawrence at the Chicago Post and, in November, began editing the weekly “Photoplay News and Comment” page.

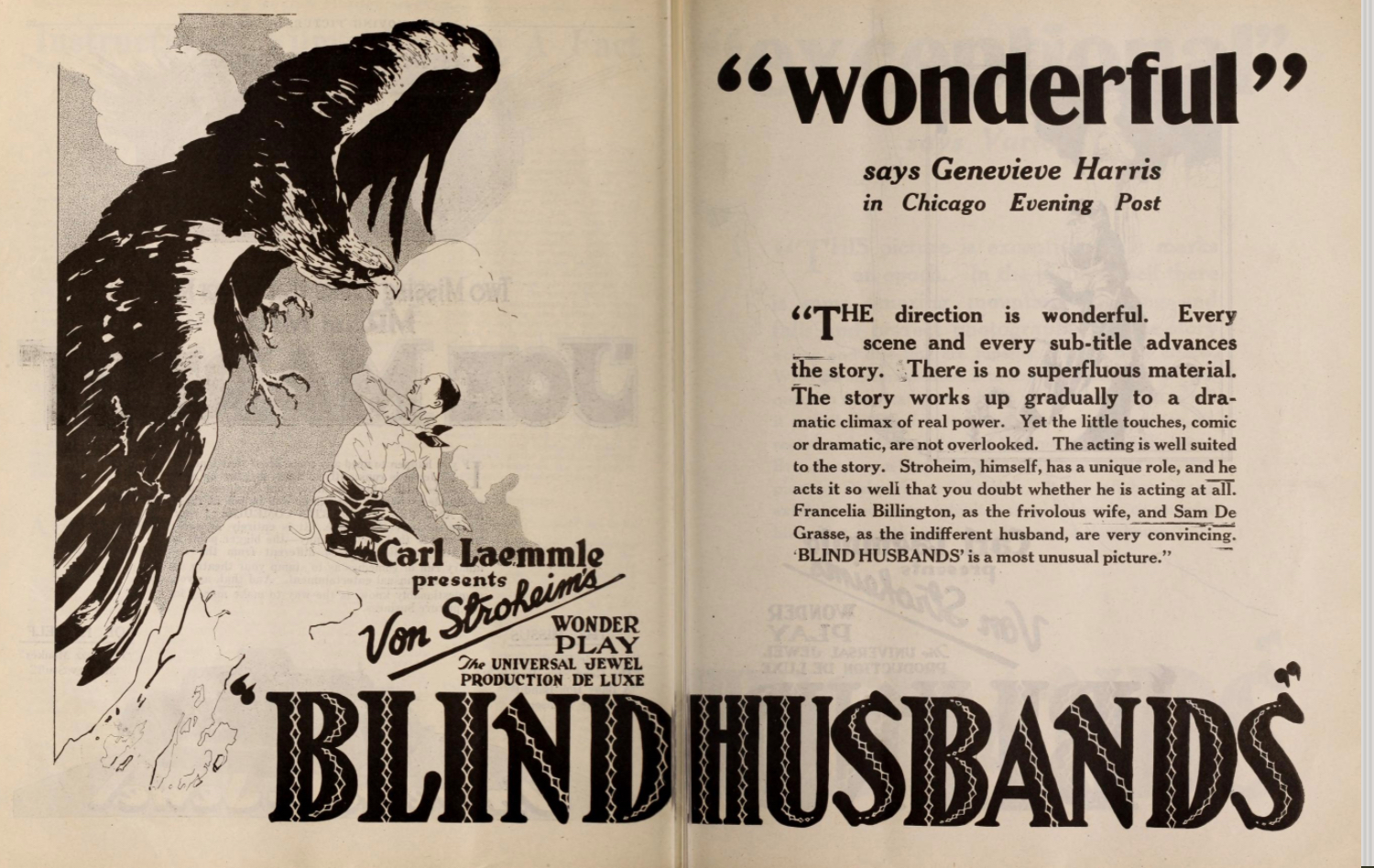

Despite the Post’s low circulation, Harris soon became an influential columnist, rivaling even Kitty Kelly and Mae Tinée in Chicago. Early on, she took readers on a surprising tour of the new Famous Players-Lasky rental exchange in the city, and the one department she highlighted was where many young women inspected and repaired film prints (“A Visit to the Film Exchange”). At the same time, she drew on local luncheon talks by Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel and Samuel Goldfish to ask what moviegoers found most important: “the artistic presentation” of a theater’s program or “the picture itself” (“Two Views on Film Problems”). She was an astute reviewer and, unlike Mae Tinée, rarely mocked a film or star. She was much impressed, for instance, with the acting, camerawork, and sets of London’s Limehouse district in Broken Blossoms (1919) (“Griffith Play Returns”). She recommended a second viewing of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), which confirmed its success, especially in the amazing Argentine section and in the moving scene between Julio, now in the uniform of France, and his father (“Second Thots on ‘Four Horseman’”). Her answer to the question “What makes a great picture?” was: “the perfect melding of story and star, that is, one in which the story provides a consistent, vivid characterization which the right player not only plays but rather brings to life” so that the picture gets “under your skin” (“What Makes a Great Picture”). Yet Harris’s interests ranged far beyond film reviewing. She was an early advocate of Mrs. Sidney Drew, not merely as a comedienne, but as a filmmaker in her own right (“Mrs. Sidney Drew as Film Director”). She wrote columns on the career of Jeanie Macpherson, Cecil B. DeMille’s chief scenario writer (“Screen Writing Distinct Craft”), as well as on Hettie Gray Baker, Fox’s managing editor responsible for the release print of a film (“Woman Editor of Film Plays”). She also took the unusual position of promoting the Society for Visual Education and its creation of “complete picture courses” as “a new and vital force” for teaching school children (“Motion Pictures in Education”).

Perhaps due to her early study at the Sorbonne, Harris also had an unusual fascination with French films. In late 1922, she devoted a whole column to the current state of French film art, summarizing the dozen film fragments shown at the second annual “Salon du cinéma” in Paris and reprinting (in translation) a lengthy quote from a Mercure de France article written by Léon Moussinac (“A French View of Film Art”). A year later, reporting directly from Paris, she quickly dispelled the myth that American films dominated the city’s screens and noted how French cinema was different. French movie stars did not receive a great deal of attention, and French audiences loved historical subjects, especially in lengthy serials, released weekly in “eight chapters of about four reels each,” with an emphasis on “picturesque backgrounds […] human interest and emotional appeal” (“French Films Show Artistry”). In late 1923, a story syndicated by NEA Services described Harris as a short story writer and “author of a course on scenario writing” as well as a movie reviewer (“Short Story Writer”). It also claimed that she was “the only American woman who wrote her criticisms of American films in French for publication in the Parisian movie magazine, ‘Le Courier.’”

Harris was the movie critic for the Chicago Post until it folded in 1934 and then began writing a Hollywood column, “Rambling Through the Studios,” for Movienews Weekly, a freely distributed newspaper (1933-1937) sponsored by a local department store in Chicago. Her last column, in early 1936, was devoted to one more important woman in the industry, Dorothy Arzner, who recently had become a producer at Columbia Pictures. In 1942, after writing publicity for the National Livestock and Meat Board, Harris joined the editorial staff of the Eau Claire Leader and Telegram and served as the woman’s page editor for the next five or six years. In 1973, obituaries named her not only as the “motion picture and drama critic for the old Chicago Evening Post” (“Obituaries” [Chicago Sunday Tribune]), but also as a publicist and freelance writer. Shortly before her death, Harris had traveled to Europe and begun writing “a series of articles comparing communist and socialist governments” (“Obituaries” [Eau Claire Leader and Telegram]).

The author made minor updates to the profile text and bibliography in November 2023.

See also: “Newspaperwomen and the Movies in the USA, 1914-1925,” Special Dossier on Early US Newspaperwomen