Hettie Gray Baker, who is as yet undiscovered by film historians, had a long and exceptional career in motion pictures. She was a writer of motion picture titles and scenarios; of library science, theatre, and fan magazine articles; and, later in life, of highly regarded books about cats. In her heyday she was scenario and film editor and eventually production editor and censorship representative at Fox studios. The range of her work, however, is not so surprising given that she was employed full-time for the motion picture industry from the early teens through the early 1950s. In 1915, Book News Monthly proclaimed that Baker was “among the leaders of the photoplay world” (331). In 1918, Photoplay described her, then working as an editor, as “the supreme authority… responsible only to [William] Fox himself” (83); and in 1922, Filmplay Journal described her career as “pioneerical,” calling her “one of the most influential people in the production of the films” (18). Although she has not figured in accounts of studio film history, Baker was clearly far from being a marginal figure in her day. She also seemed well aware of the advances she made as a woman in the film industry, commenting in 1922, for example, that she believed that her editing credit on Daughter of the Gods (1916) “was the first time that a woman’s name ever appeared on the screen as an editor” (Block 19).

Hettie Gray Baker was born in Hartford, Connecticut, was educated at Simmons College in Boston, and spent several years as a librarian at Hartford Public Library, working in the private sector at the School for Social Workers in Boston, and then as a librarian at the Hartford Bar Library, starting in July 1907, where she was, of her own account, the first woman law librarian in the United States (Block 18; Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual 1920, 317; Leonard 69). Although she had never seen a motion picture scenario before, she had—since she was a child—spent her spare time writing, and began to compose one-reel scenarios while working as a librarian. She recalls: “I sent them out to the film companies one after another, hundreds of them in a year. Lots and lots were returned, but, not in the least dismayed, I put them into new envelopes and sent them on their way to a new address. Finally I sold one. Then another was accepted. At last I was a full-fledged writer and one after another was ordered by the producers” (Block 18). By the early teens Baker had sold scenarios to six early motion picture companies—Vitagraph, Selig, Edison, Kalem, Biograph, and Mutual.

In the spring and summer of 1913, Baker took a vacation to tour the studios that were making her scenarios into films, starting in New York, traveling through Chicago to California where she stopped at Los Angeles, Pasadena, Santa Barbara, and Niles, all over the course of three-and-a-half months. She met Hobart Bosworth at the Selig studio in Chicago and, shortly after returning from her vacation, received an offer from his newly formed company, Hobart Bosworth Inc., where she took a scenario writer position and moved to Los Angeles in September 1913 (Block 18). With Bosworth’s permission, during the period she was under contract to him, she worked as a freelance writer for a variety of companies, especially the William Selig Company. At Bosworth, one of her major jobs entailed work on the adaptations of American author Jack London, and, in addition to scripting and editing, this involved writing the publicity. Although Baker receives no on-screen credit on the extant prints of the Jack London films for either writing or editing, she is noted in the press of the day for “having filmized all of his [Jack London’s] novels for the screen” (Smith 331). Indeed, one of her surviving letters to Jack London, dated November 1, 1913, details the way that she and Bosworth proposed to change plot incidents in London’s novels; another proposes strategies for timing the preparation, production, and release of an adaptation of “The Sea Gangsters.” While at Bosworth, Baker clearly did many things—even on occasion acting. The Hartford Daily Courant reported that Baker “has been on the screen herself,” taking small parts in The Valley of the Moon (1914) as well as one film that still survives, Martin Eden (1914) (2). In February 1915, the same year she was described as favoring “woman suffrage” in Woman’s Who’s Who of America, Baker announced that she was “now out of Bosworth Inc.” in a letter to Mr. John Pribyl, a literary buyer for the William Selig Company, which was accompanied by a photoplay “written with Tom Mix in mind” that Mix had already read and endorsed (Leonard 69; February 3, 1915, letter to Mr. Pribyl).

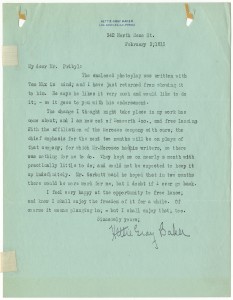

Letter from Hettie Gray Baker to Mr. Pribyl, 1915. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Baker seemed undaunted by the move from steady contract work with Bosworth to the less predictable life of the freelancer: “I feel very happy at the opportunity to free lance, and know I shall enjoy the freedom of it for a while” (February 3, 1915, letter to Mr. Pribyl). However, her freedom did not last long. She wrote again to Mr. Pribyl just twenty days later, announcing that she had already received and accepted an offer from the Reliance-Majestic Studio, where she was to work directly with D. W. Griffith (Block 19). Filmplay Journal in a 1922 article on her career further tells us that after eighteen months with Reliance-Majestic, Baker accepted a better offer from the Fox Corporation to work at their new Los Angeles studio as production and scenario editor (Block 19). Six weeks later, producer William Fox sent Baker back to New York, where she assumed her position as production editor, and, where, as her hometown paper reported in 1922, she became Mr. Fox’s “right hand man” (X2).

Fortunately for us, Baker described her duties as production editor. Her work began, she said, in the final stages after the film had already been shot and edited: “I take all the parts of the film which the film editors have considered unnecessary or unsatisfactory and have those run off for me on the screen. I pick a piece here and insert it there, clip a part from here and substitute it for another. Finally, I have the whole film run off as I have revised it. Then, if it looks almost censor-proof and yet retains enough interest and spice to hold the public, I let it go” (Block 19). At this stage, Baker was clearly working on making a film that could meet censor approval. Indeed, by the 1930s Baker had assumed the title of “censorship representative,” also referred to as “director of censorship” for the New York Fox office, her New York Times obituary tells us (28). It is worth noting that Baker does not appear to have been on a mission to clean up the movies for the sake of upholding America’s virtues. In fact, as early as 1913 she wrote a letter of protest to her hometown newspaper, the Hartford Daily Courant, protesting against “the implication that moving pictures were in any way responsible” for a murder that was being blamed on the corrupting influence of the motion picture industry (8).

There is as yet no substantive writing about the significant career of Hettie Gray Baker, yet the evidence points to her centrality and trailblazing in the fields of writing, editing, and executive work. Most of the secondary sources referenced here make only one passing mention of Baker, and many of her film credits had to be gleaned from casual contemporary references. Baker was clearly a mover and a shaker. She also appears to have had a rather wicked sense of humor, which is noted in contemporary accounts and is equally evident in the cat books she authored later in life. To give one colorful example of how she described the downside of censorship: “If it [a film] is so fixed that it will pass the censors—Lord help the people. It is usually so slow and stale that a church deacon would have a hard time not imagining that he is listening to the minister’s sermon, and you find him sound asleep—mouth open and all” (Block 19).

See also: Winifred Dunn, Katharine Hilliker, Viola Lawrence, Jane Loring, Irene Morra, Blanche Sewell, Rose Smith, “Shaping the Craft of Screenwriting: Women Screen Writers in Silent Era Hollywood”