Best known for acting with wild animals in short comic and Western adventure films in France in the 1910s, Berthe Dagmar was also the co-director—with her husband, Jean Durand—of at least three feature films: Palaces (1927), L’Ile d’amour (1928), and La Femme rêvée (1929). For Dagmar, as for many women film pioneers, being close to one of the most popular male filmmakers of the silent era was both a blessing and a curse. While she gained access to opportunities behind the camera through her acting roles in Durand’s films, her work as a director (and possibly as a producer and writer) has remained largely obscured.

Strangely enough, we know much less about Berthe Dagmar than did previous generations of film historians. I think primarily of Francis Lacassin, whose book A la recherche de Jean Durand (2004) relied on interviews, letters, and personal archives that have since been displaced or no longer exist. Although Lacassin was primarily interested in Durand’s career, he gathered information about Dagmar, especially her childhood in Normandy, her first meeting with Durand at the Lux studios in 1908, her acting roles in Durand’s films for Gaumont, and their work as independent producers and directors after World War I. But at least two problems arise when using Lacassin’s work to reconstruct Dagmar’s life and career today. First, the bulk of Lacassin’s primary sources, which included letters between Durand and French director Henri Fescourt, an interview with Durand, and various documents from Durand’s great-nephew Philippe, have gone missing. I have at least been unable to locate them in French archives. For example, the interview with Durand has since disappeared from the collection of the Commission de recherches historiques (CRH) at the Cinémathèque française. An excerpt of it was published in Georges Sadoul’s 1951 Histoire générale du cinéma. 3. Le cinéma devient un art 1909–1920 (159, 162). But only invitations to Durand from Henri Langlois in 1944 remain at the Cinémathèque française (CRH10-B1). Durand is otherwise mentioned during the meetings of the CRH that discussed early French comedy, on June 26 and 29, 1948 (CRH 54-B3, CRH55-B3).

Second, except for a few telegrams penned by Dagmar herself, Lacassin relied on secondhand accounts, not only from Durand but also from fellow screen actors and directors like Gaston Modot and Joë Hamman. Whereas Durand was apparently full of praise, others emphasized Dagmar’s “harmful, even catastrophic influence on her husband,” her “overbearing character,” and her “humiliating infidelities,” which Lacassin then reported in his book (154, 155). As far as I can tell, no account of Dagmar’s career by Dagmar herself is known to be extant. Archival materials were also never collected with the specific goal of learning about Dagmar, who has become, absent previously known primary sources, only more elusive with time.

Even though primary sources related to Dagmar are scarce, extant films as well as online resources like the Media History Digital Library and Gallica make it possible to recover some aspects of her life and career, first as an actress, and then as a director. How Dagmar developed the physical skills that she demonstrated in most of her acting roles remains unclear. So does the exact date when Dagmar began to appear in films. What I can say with more certainty is that Dagmar became well-known during her time at the Gaumont studios, where she acted in dozens of short comic and Western adventure films directed by Durand, from 1911 through 1914 or 1915. Both genres were hugely popular in France and the rest of Western Europe, probably due to the talent of the comedians and comediennes, and, in the case of Durand’s Westerns, the picturesque landscapes of the Camargue region where these films were shot. In Durand’s short comic films, Dagmar’s roles were admittedly minor compared to those of Clément Migé, Lucien Bataille, and Ernest Bourbon, who portrayed the titular characters in the popular series “Calino,” “Zigoto,” and “Onésime,” respectively. Yet Dagmar repeatedly distinguished herself, as in, for example, Calino dompteur par amour (1912), and Onésime et le gardien du foyer (1912), where she played strong fearless women who came in close contact with ferocious lions. Likewise, Durand’s Western adventure films like Coeur ardent (1912), Sous la griffe (1912), and Le Collier vivant (1913), which featured Dagmar in more prominent roles, often relied on the sensationalism of her performances with wild animals.

A comparison may be drawn here between Dagmar and the US serial queens, whose films were contemporaneous. Once described as “Europe’s Kathlyn Williams” in Picture-Play Weekly, Dagmar indeed calls to mind these “intrepid young heroine[s] who exhibited a variety of traditionally ‘masculine’ qualities: physical strength and endurance, self-reliance, courage, social authority, and freedom to explore novel experiences outside the domestic sphere” (Dench 13; Singer 221). In Durand’s films for Gaumont, Dagmar participated in lively chases, fought with wild animals, and rode horses, among other action sequences. She was, in Lacassin’s words, the “queen of the Pouittes,” which designated the troupe of performers—Dagmar, Modot, Hamman, Bourbon, Migé, Bataille, Léon Pollos, Edouard Grisollet—who regularly appeared in Durand’s films (Lacassin 153). Later, in the 1920s, Dagmar had her own series, “Marie,” discussed in more detail below, which I suspect was meant to emulate the very popular serial queen melodramas coming from the United States. It is also possible that, like Kathlyn Williams, Cleo Madison, Grace Cunard, and other US serial queens, Dagmar not only acted in but also wrote and produced some of her husband’s short films where she was the main performer.

After World War I, during which Durand and several other male members of the Pouittes served in the French Army, Durand and Dagmar’s return to filmmaking appears to have been somewhat difficult. Not only were they not as stably employed as in the early 1910s, when they worked for Gaumont, but also few (if any) of their post-war films received much popular and critical success. In 1920, Dagmar likely appeared in Durand’s serial Impéria, whose twelve episodes are now considered lost. That same year, the newspaper L’Intransigeant announced that the couple would soon travel to the United States, where they would, “with Léonce Perret, see how French methods could be combined with American craft” (“Le Cinéma”). Comoedia also reported that Dagmar had signed a “brilliant contract” with Perret, formerly from Gaumont, now at the head of Perret Productions, Inc., on the East Coast (“Les Cinémas”). But although Lacassin credits Durand with writing Tarnished Reputations (1920), produced by Perret and directed by Alice Guy Blaché, I have found no evidence that would confirm Durand and/or Dagmar’s involvement (Lacassin 242). The US press indicates instead that Tarnished Reputations was written by Perret himself.

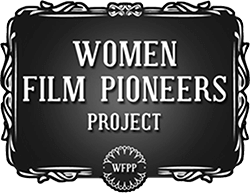

Yet more traces of Dagmar and Durand may be found in France, where, like many others in the 1920s, including Jacques de Baroncelli, Jean Epstein, Abel Gance, Marcel L’Herbier, Musidora, and Jean Renoir, Durand created his own company, Les Films Jean Durand, in an attempt to make new films as an independent producer. Although no evidence remains, Dagmar was very likely co-producer of Durand’s films during that time. Their first, and probably only, fiction film with Les Films Jean Durand was the series “Marie,” which was released in France between 1921 and 1922, and which capitalized on Dagmar’s success as “the star of the wild animals” (Desclaux 11). “Marie,” considered lost today, included four episodes, Marie-la-gaieté, Marie chez les loups, Marie chez les fauves, and Marie la femme au singe, in which, press reports tell us, Dagmar interpreted four different women who may be seen as various avatars of the same woman, further embodiments of the French New Woman on screen. Dagmar was, successively, a single housekeeper working at a castle in Camargue (Marie-la-gaieté); a former ballerina turned street performer who marries in order to provide for her nephew (Marie chez les loups); a widow in Africa soon to be remarried to her one true love (Marie chez les fauves); and a “bohemian” who performs on the street with her monkey Peter and raises her child alone (Marie la femme au singe). On the one hand, Dagmar’s characters in “Marie” were similar to the US serial queens, with several publications reporting that Dagmar—like Williams and others—did her own stunts and had been attacked by a panther on set (“Une artiste”; “French Notes”). On the other hand, it is unlikely that “Marie” enjoyed the same level of success as the US serial queen melodramas.

Besides short nonfiction films like Aigues-Mortes (1923) and Voyez comme l’on danse (1927), which Lacassin attributes to Les Films Jean Durand, Dagmar and Durand probably did not produce any more titles with their own company (Lacassin 243, 244). In 1924, at least one newspaper indicates that Dagmar performed “a sketch, very perilous in fact,” on the stage of L’Alhambra with a certain Marcel Marceau (no relation to the famous mime artist and actor) (“Courrier théâtral”). But no further evidence of Dagmar’s work on stage remains in the archive.

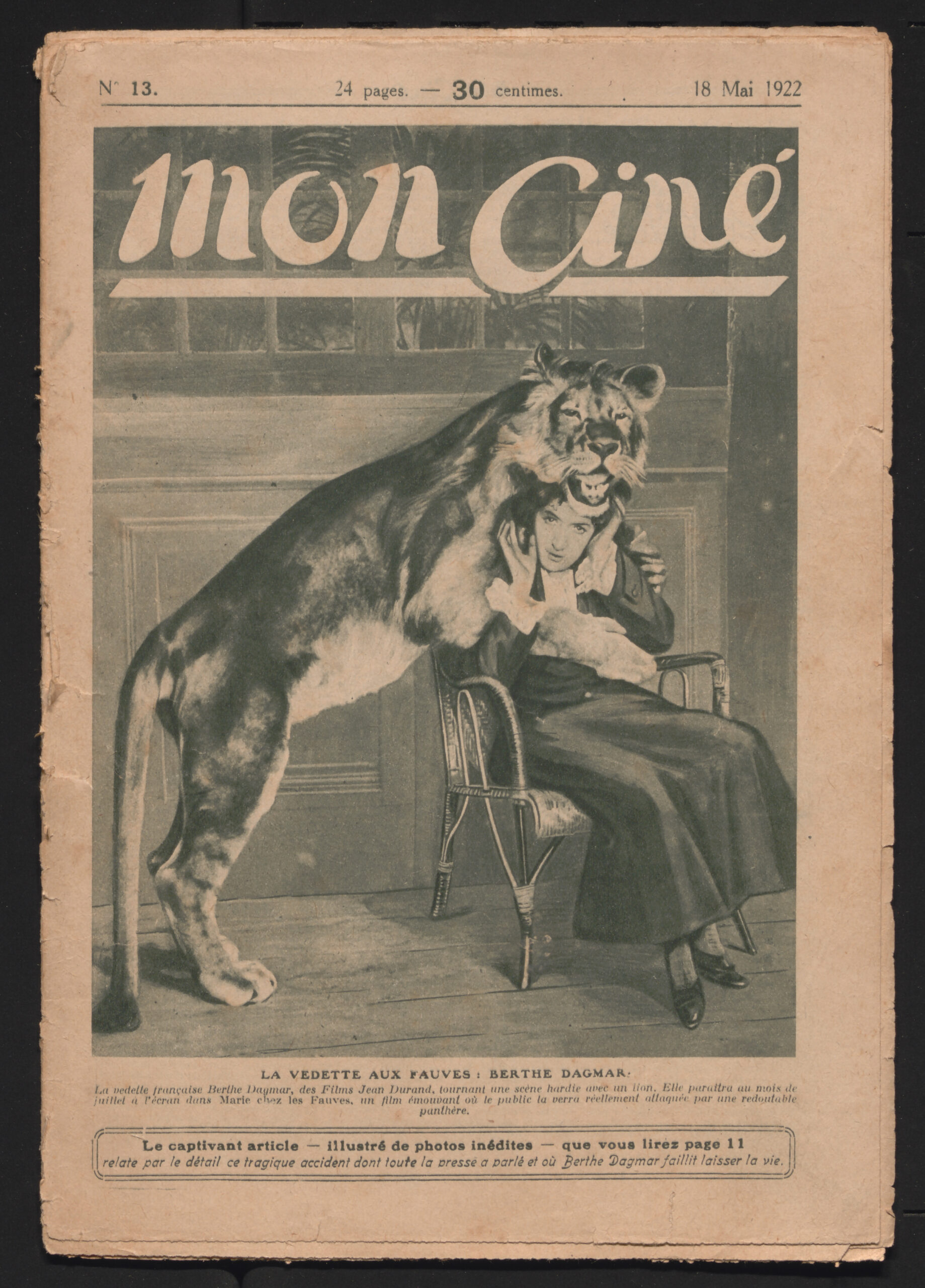

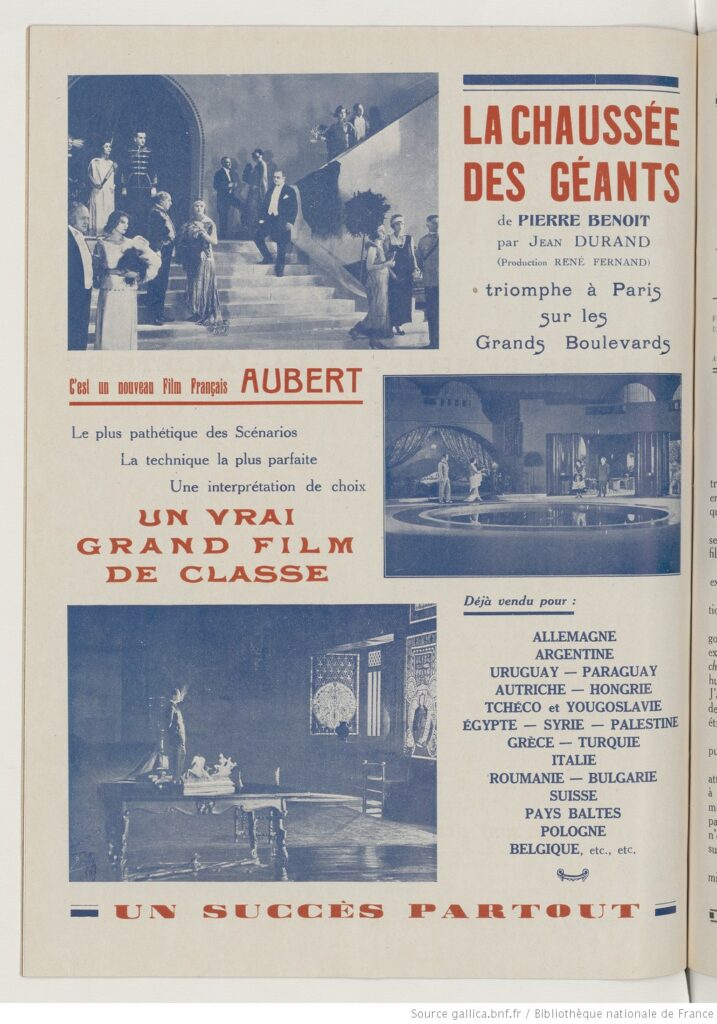

After Les Films Jean Durand ceased regular production, around 1923, Dagmar remained Durand’s closest partner. Although the feature film La Chaussée des géants (1926), which was based on a novel by Pierre Benoit, is considered lost today, articles published in French newspapers tell us that Dagmar was, with Marceau, assistant director to Durand on that film (“Votre autorisation”; “Ce qu’on a fait”; “Sous les projecteurs”). A trade press advertisement also suggests that the film had little to do with Durand and Dagmar’s previous comic and Western adventure films (La Cinématographie française). It was instead a prestige literary adaptation with lavish Art Deco set and costume design, taking place within the luxurious milieu of the wealthy upper class.

Photograph of Berthe Dagmar (in the white hat), Marcel Marceau, and Jean Durand during the filming of La Chaussée des géants (1926), from “Votre autorisation s.v.p.” Le Plaisir de vivre (5 March 1926): 8.

La Chaussée des géants, in fact, initiated a new cycle for Dagmar and Durand, one that responded to the trends of “Les Années folles,” especially Art Deco and its futuristic designs; the music hall, with its attractive leading ladies and chorus girls; and jazz music and dancing, which Petrine Archer-Straw, in her book Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s (2000), calls the “pulse beat of modernity” (109). The three other feature films in that cycle, Palaces, L’Ile d’amour, and La Femme rêvée, this time co-directed by Durand and Dagmar for Natan and Franco-Film, are available online at Gaumont Pathé Archives. Palaces, based on a novel by Saint-Sorny and shot partly on location at the luxurious Hôtel Régina in Nice, tells the story of a rich young woman (Huguette Duflos) torn between two men, her fiancé (Gaston Norès) and a charming gambler with a mysterious past (Léon Bary). L’Ile d’amour, also based on a novel by Saint-Sorny, was shot at the Natan studios in Paris, as well as on location in Corsica. Several landmarks like the Monument to Napoleon and his Brothers, and the ancestral home of the Bonaparte family, in Ajaccio, appear in the film, which focuses on a rich woman from Nice, Xénia (Claude France), who falls for a young Corsican man of modest means nicknamed “Bicchi” (Pierre Batcheff). La Femme rêvée, adapted from a novel by Spanish writer J. Perez de Rozas, begins in Seville, where a young local noblewoman (Alice Roberts) becomes infatuated with a French banker (Charles Vanel) whom she then follows to Paris. The rest of the film depicts how she struggles to adapt to a life filled with excitement without losing herself and giving in to the temptation of adultery. It includes several remarkable scenes shot on location, for example, at the now-defunct indoor swimming pool of the Lido cabaret on the Champs-Elysées, on the mighty stage of the Casino de Paris, and at the historic car-racing tracks of Montlhéry.

All three films deserve further scholarly attention. For example, L’Ile d’amour is a compelling example of how cinema in 1920s France intersected with the popular stage through casting, performance, and mise-en-scène. It also illustrates that colonialism, mediated through the popular stage and cinema, played a central yet often conveniently overlooked part in the fashioning of French modernity. Near the end of L’Ile d’amour, when Xénia hosts a lavish party at her villa, Dagmar, wearing a shimmering white dress, comes down the stairs with a group of chorus girls and then dances the Charleston with Harry Fleming, a Black performer from the Moulin Rouge. The film, which survives in incomplete form, also included another sequence, either before or after, where Mistinguett, the “queen of the music hall” in France, made an appearance on the same stage, with her white dance partner Earl Leslie. But that Dagmar danced the Charleston, which Josephine Baker largely popularized in France, is most relevant here. Terri Simone Francis tells us that Baker was, since her breakout performance in “La Revue nègre” in Paris in 1925, “a known attraction, and she was part of the growing interest in and presence of African and African American cultural events, products, and people among Parisian tastemakers” (14). With her banana skirt, dance moves, and overall aesthetic on stage, “Baker’s performance tapped into colonialist culture as she helped to generate a new iteration of it” (Francis 15). In Les Spectacles, a journalist mentioned Baker when they wrote about visiting the Natan studios during the filming of L’Ile d’amour. They not only saw Dagmar and Fleming dancing together, but they also noticed “someone in the audience giv[ing] the signal for applause: it is Josephine Baker, who has come to advise and encourage her colleague [Dagmar], for the beautiful dancer, [who is] Black [de couleur], has become, as we know, a film artist” (“On tourne”). Whether Baker was really involved in the making of L’Ile d’amour, or simply visiting the set, remains unclear. But she certainly provides a valuable reference point for L’Ile d’amour, which might have been influenced by Baker’s La Sirène des Tropiques (dir. Mario Naplas, Henri Etiévant, 1927), released in France shortly before, with several dance sequences, and also co-starring Pierre Batcheff. More importantly, L’Ile d’amour, through Dagmar’s performance and appropriation of Baker’s signature style, engages in the “colonialist culture” that shaped modernity in France.

Photograph of Jean Durand and Berthe Dagmar with Mistinguett on the set of L’Ile d’amour (1928). Courtesy of the Cinémathèque française.

Based on the extant newspapers and magazines I have consulted online, Dagmar was rarely credited, at least explicitly, as the “director” or “co-director” of Palaces, L’Ile d’amour, and La Femme rêvée. That the press danced around the role she played in the making of these three feature films is somewhat expected. Indeed, the contributions of women filmmakers working in close collaboration with their husbands during the silent era were often systematically downplayed and even erased. Whereas La Semaine à Paris clearly indicated that Palaces was “directed by Jean Durand and Berthe Dagmar” (“Palaces”), most other publications employed the terms “collaborator” and “collaboration” to describe Dagmar and her contribution to Durand’s films. To cite but a few examples, the newspaper La Presse announced that Palaces had been “directed by Jean Durand, with the collaboration of Berthe Jean Durand” (“Ecrans et studios”). The next year, Le Courrier des cinémas told their readers that “Jean Durand, with the collaboration of Mme Berthe-Jean Durand, is finishing, for Franco-Film, ‘La Femme rêvée,’ [which he directs]” (“La Femme rêvée”). On the digitized copies of Palaces and L’Ile d’amour available for viewing online at Gaumont Pathé Archives, title cards in each film likewise indicate that the film was “directed by Jean Durand, with the collaboration of Berthe Jean Durand,” and with Marceau serving as “assistant.” However, no such title card appears in La Femme rêvée.

After the release of La Femme rêvée in 1929, Dagmar apparently retired from filmmaking. Durand made one more film, Détresse, in 1929. Their names then resurfaced in 1932, when Durand and Dagmar co-wrote a serialized novel for the Breton newspaper L’Ouest-Eclair, titled Marie-la-Gaieté, based on their film series “Marie,” and illustrated with movie stills. That same year, Dagmar alone wrote “Les Animaux chez nous” for Paris-Soir. I suspect that Durand and Dagmar—like Alice Guy Blaché around the same time—might have turned to writing in the popular press as a way to make ends meet. Dagmar died of causes unknown to historians in 1934, about twelve years before Durand. The two had no children, but their personal archives ended up, at least for a while, in the care of Durand’s nephew Louis Durand and great-nephew Philippe Durand (Lacassin 211). If extant, and when located, these archives could reveal more about Dagmar’s work as a film director in the 1920s.