Katharine Hilliker, best known for her work as a team with her husband, Harry H. Caldwell, began her career writing silent motion picture titles and shaping European films for release in the United States before becoming a freelance production editor for Samuel Goldwyn, United Artists, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Fox Film Corporation. As a production editor, her responsibilities, she states in her resume, involved “consultation on story and cast and the supervising of scripts before production to the job of preparing the picture, after it was shot, for theater presentation.” Hilliker’s papers, which include a number of personal letters, are a rich source of information on the films she edited and titled and the people she worked with, including producers Harry Rapf, Irving Thalberg, and Samuel Goldwyn; director F. W. Murnau; and Fox studio head Winfield Sheehan.

Hilliker was born Katharine Clark in Tacoma, Washington. Her father died when she was young, and she was later adopted by her stepfather, thus becoming Katharine C. Prosser. She attended high school and college in Savannah, Georgia, before moving to San Francisco to become a society editor for the Berkeley Independent in 1909. In addition to working as a society editor, she was a proofreader and rewriter. From there she worked at other publications in the San Francisco area including the Oakland Inquirer and The Call.

It is at The Call where she met her first husband Douglas “Bill” Hilliker. Douglas Hilliker was a talented graphic designer who would also work in the motion picture industry designing the publicity posters and materials for studios such as Paramount. In a strange twist of fate, Bill Hilliker would later remarry and have a daughter who would marry Katharine’s son from her second marriage. But it is from Bill Hilliker that Katharine became familiar with and learned quite a bit about graphic arts, which would aid her in collaborating with art departments later in her film titling and editing career.

Her journalism career led her to New York, where she became the motion picture editor for the New York Morning Telegraph. In 1915, she left journalism to become an associate editor in the scenario department at Universal Film Manufacturing Company. Reaching a salary cap and figuring there was not much of a future in reading, in 1917 she resigned and became an assistant to Vivian Moses, the director of publicity at Lewis Selznick and Adolf Zukor’s Select Pictures, where Hilliker wrote publicity copy for magazines and newspapers. That year she also published an article in Motion Picture magazine in which she was identified as a scenario editor and gave advice to aspiring writers. A 1927 profile of Hilliker reports that she wrote the titles for The Lesson, which Select released in 1918 (106). In a small personal statement, Hilliker reminisced that the film had sat on the shelf for six months and over that time several attempts were made to make it releasable with little success. Seeing this as an opportunity to get into the production circles, Hilliker wrote new titles and working with a cutter reedited the whole film. When it was released, after Hilliker had left Select, the new version made back production costs and a profit.

During World War I, she joined George Creel’s staff as an assistant editor for the Division of Films of the Committee on US Public Information, writing publicity and helping to make films shot in military camps and munitions factories. For these pictures she traveled extensively, visiting the locations and overseeing various aspects of production. During this time she also returned to publicity, working for magazines like Vogue and Vanity Fair writing up and conducting star interviews and putting together layouts. It was while working for the magazine Film Fun that the editor, Jesse Nile Burness referred her to C. L. Chester, a travel and comedy picture producer.

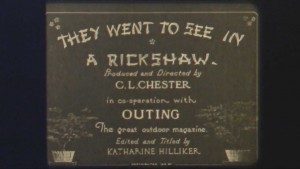

Following the war, Hilliker joined the independent company C. L. Chester Pictures Corporation as a production editor, which meant overseeing scripts, cameramen, and cutters. According to the Motion Picture Studio Directory and a “List of Pictures” found in her personal papers, she edited and titled the first two Torchy comedies and Toonerville Trolley comedies at Chester Pictures (306). All Chester Pictures would eventually be absorbed by Educational Pictures, which sadly lost the majority of their film library to a laboratory fire in 1937.

Hilliker’s primary contribution at Chester Pictures was writing the titles for the “Chester Outing scenics,” or “screenics,” a series of short films produced by Chester Pictures for Outings, an outdoor magazine. These travelogues depicted people and scenery in locations ranging from the Philippines, China, and New Zealand to Taos, New Mexico, and Yellowstone National Park. According to the Los Angeles Times, the Chester Outing scenics “brought us to every part of the picturesque old world, and their beauty made us glad. Too, their humor made us laugh.” This humor, the Times noted, was to be found in the intertitles, which we know were written by Hilliker (III1). A 1920 Photoplay article describes Hilliker’s approach to titling the scenics: “If you give her a waterfall scenic, does she write gentle things about the waterfall whose splashes clear bring sweetest music to our ear? She does not. She turns it into a half-whimsical, half-hilarious treatise on prohibition” (124). While with Chester, she would title over fifty scenic pictures, and meet her second husband, a man with an illustrious military career, H. H. (Harry Hadley) Caldwell.

In 1920, Hilliker was hired by S. L. “Roxy” Rothafel, who owned the Capitol Theatre in New York, to write English titles for Ernst Lubitsch’s German film, Madame DuBarry (1919). She was repeatedly called upon to title European films, including the Weimar era German classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), for which, according to Motion Picture, she wrote the prologue and epilogue of the US release print (106). In 1922, she began part-time work as an assistant to Major Edward Bowes in the Goldwyn Company New York office. In her resume, Hilliker explains that her work at Goldwyn involved taking care of all possible censorship problems and that she had quite a lot of responsibility, as she “passed on the possibilities of pictures offered for distribution [and] sat in on all editorial matters.” This resume, a remarkable narrative of eighteen years of work experience, is perhaps the most comprehensive description we have of the function of a story editor as well as that of a film editor and title writer between 1915 and the end of the silent era. Its value is in its confirmation of the early participation of women in so many aspects of motion picture pre- as well as post-production work.

In 1921, Hilliker married Harry H. Caldwell, the vice president and general manager of the C. L. Chester Pictures Corporation, which produced the Chester Outing scenics, and the two, often referred to as The Captain and Miss Kit, began titling films as a team. A 1927 profile of the couple published in Motion Picture magazine describes their collaboration: “The two look at a picture two or three times and write down ‘scratch’ titles. They each write their own titles. Then they compare them. Sometimes the title of one is used, sometimes that of the other, or thirdly, they often combine or work out a title together that satisfied both” (106). In order to avoid being separated, the couple often signed joint contracts, at a reduced salary, sharing credit for titling and editing the films they worked on from this point forward. However, it appears that Hilliker enjoyed more prestige within the film industry than her husband did. In a 1925 letter to her agent, Cora Wilkenning, Hilliker complains bitterly that “a lot of dumb Doras seemed to think I wrote his stuff for him.” This impression may have been due to the fact that it was generally Hilliker who pursued and negotiated the joint contracts. Even outside the industry, Hilliker had made a name for herself. A Washington Post article about the new profession of title writing and the couple notes, “Mrs. Caldwell had herself won such distinction her maiden name was retained” (n.p.).

Soon after their marriage, Hilliker and Caldwell moved to Los Angeles to title Samuel Goldwyn’s releases of two Italian feature motion pictures, Théodora (1919) and The Ship (1921), that Goldwyn had imported. In a 1922 Photoplay article, Hilliker describes her role in rescuing problem-plagued films, compensating for a miscast actor or covering up missing scenes in Goldwyn’s print of Theodora, for instance. During this period, Hilliker became increasingly frustrated with cutters who would refuse to make changes she suggested, the cutters often claiming the reasons were too technical for her to understand. Enlisting the help of a friend in the cutting room, Hilliker learned all about the various editing practices, from cutting to other post-production effects. From then on, if the cutters refused to make the changes she suggested, she would do them herself.

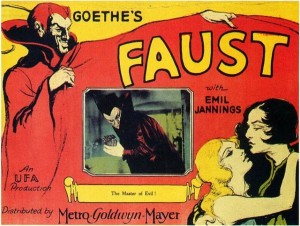

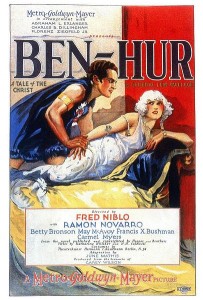

In 1922, according to the Moving Picture World, the couple began work as personal assistants to June Mathis, producer at the Goldwyn Company, where they would become heads of both the film editing and what was then called the “art title” department (732). However, they were not given the creative freedom they would have liked, and in January 1923, they informed Mathis that they would return to New York upon completing their work on Lost and Found on a South Sea Island (1923), complaining in a 1923 memo to her that “a job that has nothing to commend it but the salary involved is not much of a job.” For the next two years, the couple freelanced, working for large companies, the US First National Exhibitors Circuit, the German UFA, and independent producers Jules Brulatour and E. K. Lincoln, as well as the Canadian government, “whipping productions into shape for theater showing,” she writes in her career resume. In 1925, Katharine Hilliker signed an individual contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which had absorbed Goldwyn in 1924. Her signing was an important enough event to receive mention in the Moving Picture World (451). Her resume says that she was “adviser on editorial problems; trouble-shooter on censorship snags; [and was] responsible for final editing and titling of productions assigned.” Hilliker moved once again to Los Angeles, although Caldwell initially stayed behind in New York. Her letters to Caldwell during this period vividly describe working with Harry Rapf and Irving Thalberg. She was, she says, thrilled to be working with Thalberg on Ben Hur (1925), although the film was plagued by production problems. Ultimately, though, her experience at the studio was not happy, and she would write to her husband in June 1925 of what she saw as the chaos and inefficiency of the studio system. With three “continuity men” on the same story, she complained, the final continuity script made no sense. “I have yet to read a continuity here,” she writes, “which is not as full of holes as a Swiss cheese.” In an effort to keep Hilliker, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer eventually gave her a suite of offices with her own screening room and even revised her contract to include Caldwell. However, the work remained unbearable to the couple, and before they left the studio, they requested that their names be removed from The Scarlet Letter (1926), the Lillian Gish star vehicle credited to writer Frances Marion.

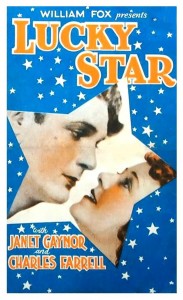

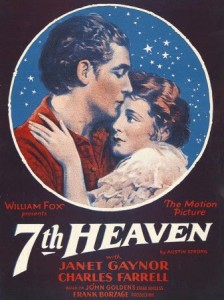

In July 1926, Hilliker and Caldwell signed a contract with Fox Film Corporation, where, according to publicity that they may have written themselves as part of a letter to Sol. W. Wurtzel, general superintendent of the company’s West Coast studio, they would be “supervising editors and personal aides to Wurtzel.” Further, in addition to supervising scripts and titles, they would have control of the final edit on every production, and be given full publicity credit as production editors for each film they cut, unusual contract stipulations for editors at the time. Evidence that Fox lived up to the contract is the advertisement for Seventh Heaven (1927), which features a photograph of the couple, identified as the film’s “editors and title writers,” accompanying photos of the film’s director, Frank Borzage, and its stars, Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell. The pair were permitted a great deal of creative control over the films they worked on, and were trusted by the studio’s directors, including F. W. Murnau. Hilliker and Caldwell consulted on story and cast, supervised scripts, and even wrote new sequences in order to fill narrative gaps.

Given Hilliker’s comfort around the drawing table and graphic design, she would often work with the art department giving input on the artistic design of the title cards as well. It is speculated that on the film Sunrise (1927) it was Hilliker who conveyed Murnau’s vision for the title cards to the art department, resulting in the famous animated title card “couldn’t she get drowned” along with the stylistic elements of the other title cards. Hilliker’s thirst for learning and taking on new projects and skills raises questions and speculation about the connections between script and title writers, editors and the art department, and how they all worked together. Hilliker provides one of those links, as according to her family, she was fastidious about overseeing her titles down to the last detail, including design and how and when they would appear on screen. In both the MoMA archives and the personal family collection of papers, there are hundreds of drafts of titles the couple worked on, some with the most minor change of word choice or word order. That fastidiousness and attention to detail may have been part of the reason they worked so well with the stern F. W. Murnau. It has been said that the couple were two of the only people on the set or otherwise that could openly poke fun and joke around with the director. Looking through Hilliker and Caldwell’s papers, one finds various drafts to get the titles just right, correspondence working to the same end, and other notes, letters, and memorandums all in an effort to support the creative vision of the director. She and Caldwell’s dedication to the director and his vision seems to imply more of an artistic and personal partnership with Murnau than a mere professional one.

According to Janet Bergstrom, Hilliker and Caldwell were so essential to the endangered production of City Girl (1930) that they effectively were responsible for “saving Murnau’s vision” of the beleaguered film (448). During this period, publicity for Hilliker, says Bergstrom, often described her as “one of the best known title writers in the industry” (451). The couple’s activities were even reported in the society pages of the Los Angeles Times, as in the 1928 coverage of their travels (C15).

The advent of sound brought an end to Hilliker’s film career. Intertitle writers did not fare well in the transition to sound, for theirs was a skill developed for the silent cinema. Eventually, independent producer Sol Lesser hired Hilliker to write a sound version of the popular stage play “Peck’s Bad Boy.” However, her script was scrapped when Lesser sold the property to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which released the film in 1934. In 1932, after being turned down for a contract with Universal, the couple signed a two-month agreement with Joe Brandt at World Wide Pictures in New York. According to their contract, their role there would be to “read stories, prepare synopsis of such stories; read treatments, continuities, dialogues, etc., and [give] opinions on them.” The financial difficulties of World Wide Pictures, however, brought an end to Hilliker’s motion picture career. Despite having had a creative hand in many of the most prestigious films of the silent era, Hilliker found herself out of money in Los Angeles, selling off her belongings in order raise enough cash to return to her husband and son in New York.

Hilliker returned to writing with some success. She contributed to the WPA, collecting oral histories, and she and Caldwell wrote three plays together. Following his death, she returned to magazine writing, working for various publications. She lived out the rest of her life in New York City, maintaining her independence by writing and creating ads for The Grosvenor, where she lived. Katharine Hilliker, as Katharine Clark Caldwell, and her husband are interred in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

With additional research by Bethany Czerny

See also: Hettie Grey Baker, Winifred Dunn.