A Report on the Recent “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto”

Kate Saccone recaps Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, which took place recently in Pordeneone, Italy (September 30-October 7, 2017):

The 36th edition of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, the world’s foremost international silent film festival, took place a few weeks ago in Pordenone, Italy. This year marked my first visit to the annual event and I was far from disappointed. Over the course of the week, I saw delightful, challenging, and provocative films across a broad range of genres and from around the world. I was moved by Dimitri Kirsanoff’s Impressionistic Ménilmontant (1926) and Yasujiro Ozu’s neo-realistic Tokyo no Yado (1935), charmed by comedies like The Deadlier Sex (1920) and She’s a Prince (1926), and perplexed by Ubaldo Magnaghi’s Mediolanum (1933). From European Westerns and World War I documentaries to a recently restored fragment of the Louise Brooks film Now We’re in the Air (1927), I know I will be processing everything I saw (and the wonderful musical accompaniment that I heard) for weeks to come.

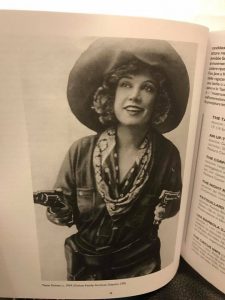

I attended the festival with a keen interest in seeing how many women film pioneers were represented by the programming and, as soon as I got my hands on the hefty catalogue, I looked for familiar names from our lists of published profiles, assigned profiles, and unassigned/unresearched women. I found pioneers in many different parts of the festival, though none were directly highlighted this year (except perhaps Texas Guinan, whose gun-toting image appears in the catalogue twice). For example, Florence Lawrence appeared in The Taming of Jane (1910) and Her First Biscuits (1909), both included in the timely “Nasty Women” program, which was co-curated by WFPP contributors Laura Horak and Maggie Hennefeld and focused on a wide variety of unruly, messy, and disruptive women. Marion Leonard’s Lucky Jim (1909) was also a part of this series, as was Florence Turner’s vehicle Everybody’s Doing It (1913). In the latter, Turner, who would go on to direct, produce, and star in Daisy Doodad’s Dial (1914) the next year, appears as a young woman who tries to woo a surly bachelor. While her skills as a facial contortionist were not utilized as much here, Turner’s expressive eyes and mouth were instantly recognizable. Elsewhere in the festival’s lineup, episodes of the Italian serial Il Fiacre n. 13 (1917)—featuring director/producer/screenwriter/actress Diana Karenne in episode four—were included in a series dedicated to the seventieth anniversary of the Cineteca Italiana.

La Fiancée du Volontaire (1907), directed by Alice Guy, was shown as part of the mid-week Tableaux Vivants presentation, where Valentine Robert went into fascinating detail on the relationship between painting and early cinema. An adaptation of the play “Anna-Liisa”—by assigned Finnish source author Minna Canth—was screened as part of a focus on Scandinavian cinema and French actress/stuntwoman Berthe Dagmar (profile forthcoming) made more than one appearance in the “Beginnings of the Western” program. Tungusi (1927) and Bukhara (1927), both edited by assigned Russian pioneer Yelizaveta Svilova from unused footage from Dziga Vertov’s A Sixth Part of the World (1926), were included in the “Soviet Travelogues” section. Russian film director Yuliya Solntseva (profile forthcoming) was seen in Aelita (1924), which was part of the annual “The Canon Revisited” strand of the festival (the costumes for the film were designed by another assigned pioneer, Aleksandra Exter).

I was particularly charmed by Manden uden Fremtid/The Man Without a Future (1916), a Danish comedy/Western written by Harriet Bloch. According to the WFPP profile on the prolific screenwriter, not only was this her favorite film, but she also wrote the cowboy part specifically for actor Valdemar Psilander at his request. The story follows an energetic cowboy who falls in love with a rich young woman. While she certainly likes him, she’s not impressed by his profession. However, the film is more than just a cross-class romantic comedy. Bloch’s cowboy is a nuanced mixture of rowdiness and sensitivity and his paramour, Grace, is very likeable.

The Night Rider (1920), starring Guinan, was a strong entry in the “Nasty Women” program and very fun to watch. Clad in leopard-print chaps and a big hat, Guinan stars as a ranch owner who is faced with ongoing nighttime cattle raids. Her character is spunky and outspoken: when told by locals she probably needs a husband to help protect the ranch, she responds “I never met a man yet fit for a husband.”

Most of all, I was blown away by the experience of watching the closing night film, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927), accompanied by the Orchestra San Marco of Pordenone. The film, starring the equally charismatic Ramon Novarro and Norma Shearer as lovers ultimately not destined for each other, was a nuanced and romantically tragic tale. Marian Ainslee and Ruth Cummings, two women from WFPP’s assigned pioneers list, wrote and created the well-placed intertitles, which were a mix of the comedic, somber, practical, and creative (at one point, the titles are used to illustrate the characters’ passion and excitement for each other, expanding as they say the other’s name). It was a strong ending to a wonderful week of celebration—of powerful and affecting films, of the tireless archivists who care for them, of the musicians who transform them, and of the numerous women and men who created them. I’m already looking forward to next year.