Elizaveta Thiemann is the first credited female film director in Russia, which is a substantial accomplishment in and of itself. But she is best known for her work as a producer. Together with her husband Paul Ernst Julius (Pavel Gustavovich) Thiemann (1881-1954), she managed one of the most successful film companies in pre-revolutionary Russia, known, at different times, as Thiemann and Rheinhardt Trading House, Russian Golden Series [Russkaia zolotaia seriia], and Era. In his memoirs, director Viacheslav Viskovskii writes about the “missises” [“khoziaiki”] who were often in charge of film company affairs no less than their producer husbands. Apart from “madame Thiemann,” he mentions “madame Khanzhonkova” (Antonina Khanzhonkova, the wife of legendary film producer Alexander Khanzhonkov), who he describes as “a very business-like lady, yet ignorant in literature and art” (Viskovskii 4-5). While most characterizations of Khanzhonkova in memoirs are similar to Viskovskii’s, or even more negative, Thiemann is usually described more positively: director Vladimir Gardin mentions “Thiemann, with his wife who knew the film industry quite well and took part in directing films” (Gardin 116); and cinematographer Alexander Levitskii recollects the Thiemanns very favorably, writing that, “Thiemann was set apart [from other producers] due to his high level of culture as well as decency. His wife Elizaveta Vladimirovna was also a great admirer and expert of art. Their house was often packed with Moscow writers, artists, and actors” (Levitskii 67). While the prominent role played by Elizaveta Thiemann in Russian film history was emphasized by memoirists, as well as later film scholars like Neia Zorkaia, Vladimir Mikhailov, and Denise J. Youngblood, it is hard to determine the extent of her contributions; her name was rarely mentioned in the trade press, and there are few surviving documents from the time.

We cannot even be sure about the spelling of Elizaveta’s maiden name, which she returned to at the end of her life (it seems to have been “von Mickwitz” in Russia and “von Minckwitz” in emigration), nor about her birthdate (1889 in the official family documents, 1885 in one of the earlier papers). Either way, she seems to have started her career in literature and arts quite early. In 1902, she corresponded with the famous Russian and Ukrainian writer Vladimir Korolenko whose short stories she translated into German, to his satisfaction (Korolenko 331). His daughters and biographers, Sofia Korolenko and Natalia Korolenko-Liakhovich, also note that Elizaveta Mickwitz had published several translations under the pseudonym Heinrich Harff (Korolenko 331). Between 1900-1905, several more translations of Russian prose into German were signed by this name: among them, the works of Maxim Gorky, Aleksandr Kuprin, and Vikenty Veresaev. These were probably done by Elizaveta as well—which makes 1885 a much more realistic birth year than 1889, unless she was a child prodigy. It is also likely that she herself wrote fiction. In 1931, a short story entitled “She Remembered” by a certain E.V. Mickwitz was awarded the second prize at a small literary contest in Tartu (at that time, Elizaveta had already emigrated from Russia and indeed spent some years in Estonia) (Shor et al. 340-341).

In 1909, Elizaveta married Paul Thiemann, who soon afterwards established a film production and distribution company together with Friedrikh Rheinhardt. As Ivan Kavaleridze, sculptor and film director, recalls:

The company belonged to Pavel Gustavovich Thiemann, a German born in Moscow, on Kuznetskii Most. At the age of twenty-eight, he married Elizaveta Grigorievna [sic] von Mickwitz; he used to work under the supervision of her father at some enterprise and proved himself a man of business. The daughter received five thousand rubles as a dowry. The sensible and practical newlyweds decided to invest this money into a film. Death of Ivan the Terrible, the first film of their studio, was scandalous but commercially successful. (Kavaleridze 47)

Paul was born in 1881; if Kavaleridze is accurate, the wedding indeed coincided with the foundation of P. Thiemann and F. Rheinhardt Trading House. The beginnings of this successful enterprise were described in the trade press frequently, but Elizaveta’s name was never mentioned (“Za piat’ let”; “Pavel Gustavovich Thiemann”). However, according to various memoirs, her role in Paul’s business was evident (in fact, it is the extent of Rheinhardt’s participation that still remains unclear to film scholars). It is difficult to say which of her father’s enterprises Kavaleridze had in mind, but we know that before 1909 Paul was employed by the Russian office of Gaumont (“Za piat’ let”), whereas Vladimir Mickwitz made a career as an engineer and, for his services in that field, was granted a barony. Later, however, Vladimir was actively engaged in the family film business and even became the director of his son-in-law’s trading house (“Khronika” [May 31, 1916]).

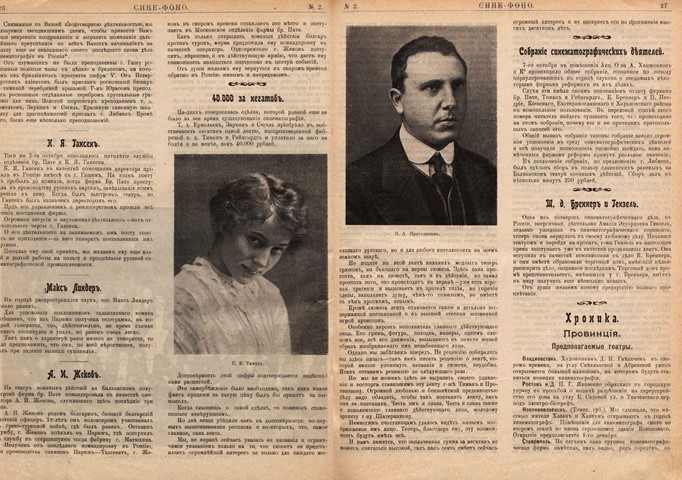

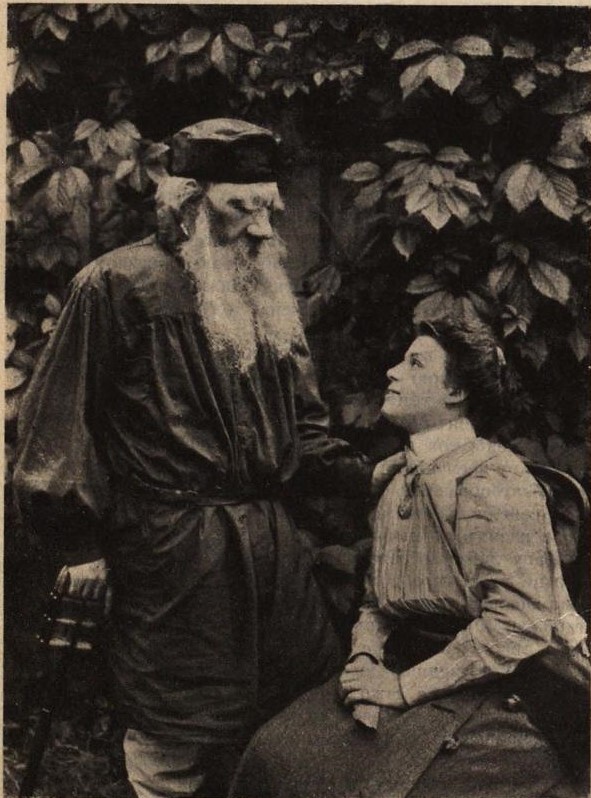

One of the most significant films of the new trading house was The Passing of the Great Old Man (1912), a chronicle of the last days of Leo Tolstoy during which he left his home and family and, after a day’s train journey, died at a rural railway station. The film was directed by Elizaveta Thiemann and Yakov Protazanov, who later became one of Russia’s most prominent film directors (and who made his screen debut, as an actor, in Thiemann’s first blockbuster, Death of Ivan the Terrible [1909]). The events depicted in the film took place only two years earlier, and the memory of Tolstoy’s death was still fresh and scandalous. This, along with the fact that the film shows Tolstoy’s wife Sophia Andreevna, still very much alive in 1912, in a rather unfavorable light, earned it severe criticism. Yet some reviewers gave it considerable credit and argued that it would play an important role in film history. For example, one critic wrote: “In this picture, you will find neither trendy tricks, nor a plot that would affect your nerves. The simplicity of the plot itself, of the acting, and everything revealed on the screen is where the world tragedy lies. That is what causes silent but scalding tears. That is what fills the viewer’s soul with something hard but also mild and clear. Aside from the plot, this film is marked by detailed staging and profoundly vivid performance” (“40.000 za negativ”).

The Passing of the Great Old Man is the only official directorial credit in Elizaveta’s filmography, whereas Protazanov enjoyed thirty plus years of a distinguished film career in Russia, France, and Germany. It is no wonder that at some point this early motion picture became associated with Protazanov alone, while Thiemann’s contribution is usually overlooked or misrepresented. For instance, Mikhail Arlazorov, the author of an essential biography of Protazanov, notes that Thiemann was “assisting” Protazanov (Arlazorov 165). If he had any evidence for this assumption, he did not cite it in his book. Surviving contemporary sources suggest nothing of the kind; as the aforementioned critic wrote: “We cannot help expressing our amazement and admiration for Ms. Thiemann and Mr. Protazanov who directed the film. One should have enormous love and self-hearted devotion to the cinema to direct a film in the way they did it. Hats off to them!” (“40.000 za negativ”). Additionally, portraits of Thiemann and Protazanov were published next to each other. One may argue that Elizaveta received equal billing because the producer wanted to promote his wife, but, in pre-1914 Russia, directors were neither mentioned in the credits nor on posters, and their names were rarely discussed outside of the trade press.

Elizaveta Thiemann as Alexandra Tolstaya in The Passing of the Great Old Man (1912), Sine-Fono no. 2 (1912).

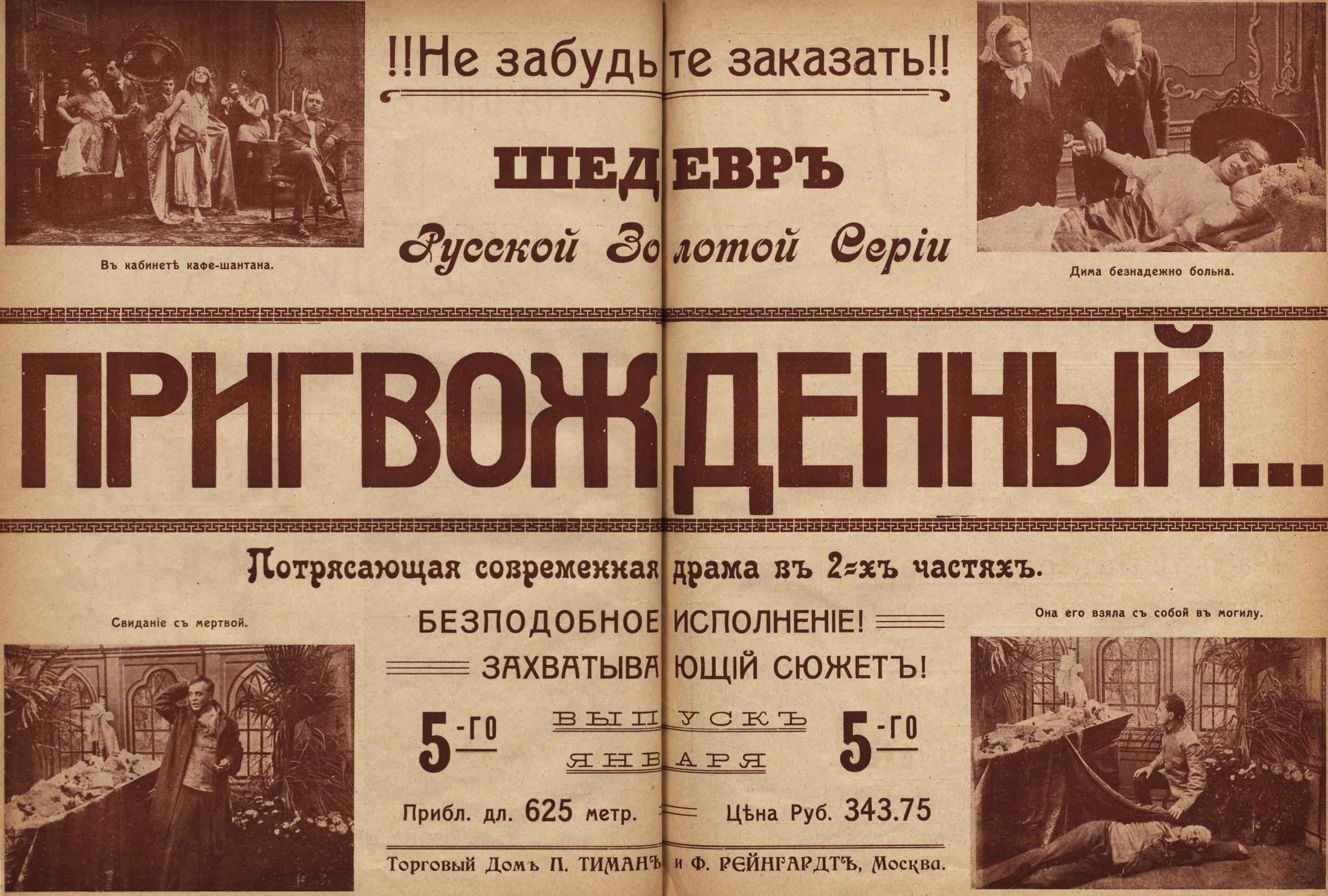

Elizaveta also made her debut as an actress in The Passing of the Great Old Man, playing Tolstoy’s youngest daughter Alexandra. Her manner onscreen seems to meet the average level of Russian screen acting for 1912, which, we must admit, was not particularly high. She acted in four more films: The Nailed One (1912), For the Honor of the Russian Banner (1913), How the Child’s Soul Cried (1913), and Fleeting Dreams, Carefree Dreams Are Dreamed Only Once (1913). In the early 1910s, Russian film reviews were often laconic, and acting was rarely discussed. However, Thiemann’s performances received noticeable praise. For example, a review of The Nailed One stated: “Ms. Thiemann, who played Dima, acted very successfully” (“Sredi novinok” [1912]). Elizaveta’s work in Fleeting Dreams also received favorable criticism: “Ms. Thiemann and Mr. Volkov, who played the leading parts, are excellent. Their performance breathes with poetry and lyricism” (“Sredi novinok” [1913]). After 1913, following the rise of the first Russian film stars—the so-called “Kings” and “Queens” of the screen—Elizaveta refrained from acting. She was wise enough to perform only while there were still no specific requirements for film acting and gave up her screen career when such requirements were established. The success of her company must have been more critical for her than her acting career. By late 1913, Thiemann and Rheinhardt had its own set of film stars—including such major names in the history of Russia cinema as Vladimir Maksimov and Olga Preobrazhenskaia—most of whom had proper theatrical training.

Photo of Paul Thiemann’s pavilion with the the cast and crew of The Love of a Japanese Woman (1913), Kino-gazeta no. 27 (1918).

According to the most fundamental filmography of early Russian films, compiled by Veniamin Vishnevskii, The Passing of the Great Old Man was the only film directed by Elizaveta Thiemann. However, Vladimir Gardin recalls that she “took part in directing films” (Gardin 116; emphasis added). We do know that she was frequently on set. One of the rare surviving behind-the-scenes photos for Russian Golden Series, as the company was known by 1913, depicts the cast and crew of The Love of a Japanese Woman (1913). While Elizaveta is not mentioned in the credits for this film, which was a Russian production with a partially Japanese cast released in the summer of 1913, she is at the very center of the picture (“V pavilione P. G. Timana”). Does her presence mean that she participated in the filming, or was she just curious to meet actors from an exotic country (including the legendary Hanako)? She certainly contributed to the studio planning as much as her husband. According to Levitskii’s memoirs, it was Elizaveta and Levitskii himself (but not Paul) who suggested one of the most ambitious projects of early Russian cinema, an adaptation of Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1915) in two parts (Levitskii 64-65).

The logo for Russian Golden Series. Reproduced in Rannii russkkii kinoplakat, 1908-1919 (2019), p. 73.

Russian Golden Series was an outstanding cinema enterprise. Being active in both production and distribution, it gained a reputation for adaptations of classical and contemporary literature, the most notable of them directed by Protazanov and Gardin. Many of these films played a significant role in the the history of Russian cinema, including: Protazanov’s Anfisa (1912), which was based on Leonid Andreyev’s play, and Plebei (1915), based on Strindberg’s “Fröken Julie”; Gardin’s Anna Karenina, A Nest of Gentlefolk, and The Kreuzer Sonata (all 1914); and The Keys to Happiness (1913), an adaptation of Anastasiya Verbitskaya’s scandalous bestseller, and War and Peace (1915), directed by both. However, soon after the start of World War I, the company faced a severe crisis.

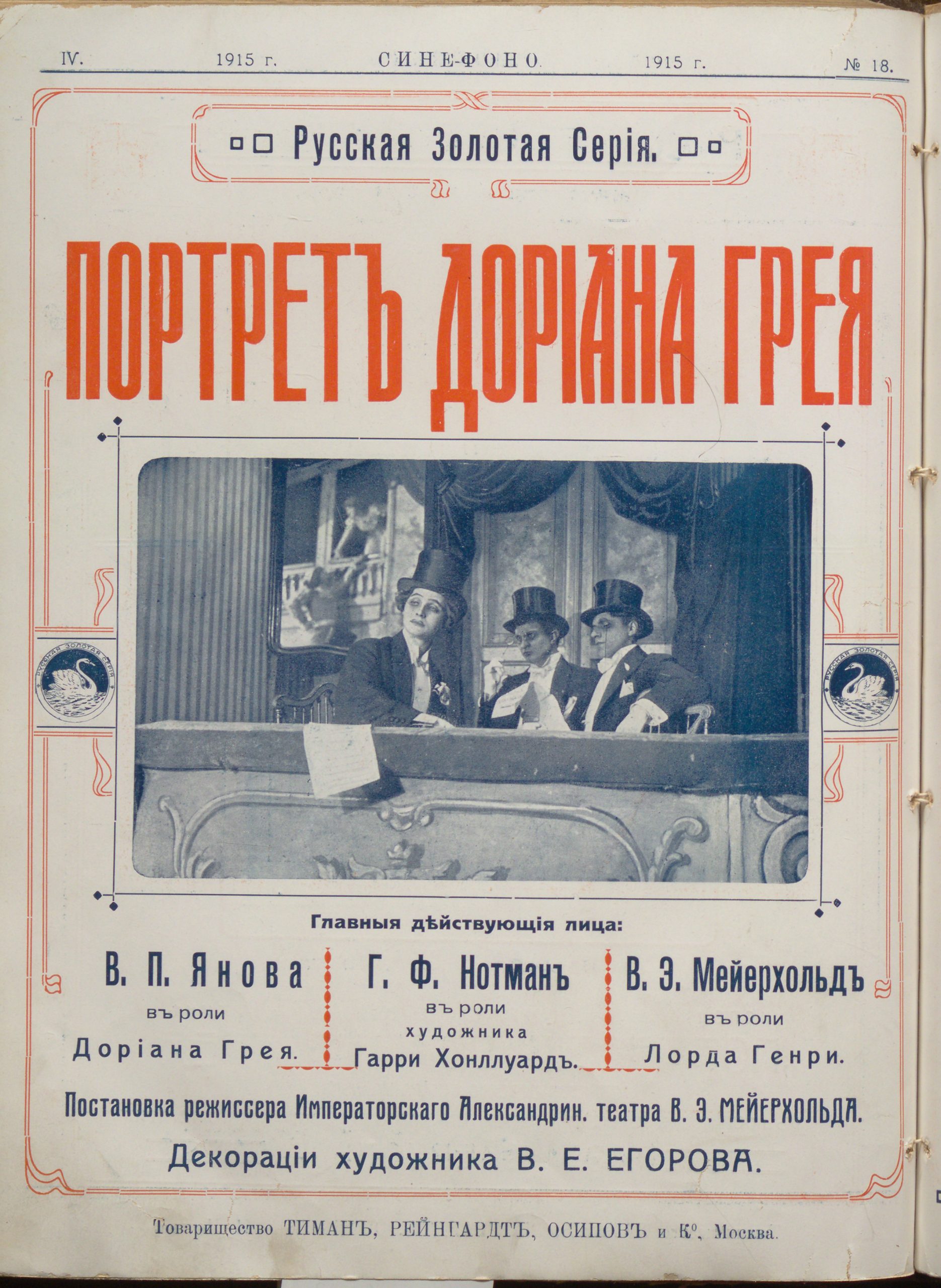

Symbolist writer Aleksandr Kursinskii, the studio’s principal screenwriter who also served as its literary director, left his job to join the army field forces (Kovalova and Ranneva 366-388). Vladimir Shaternikov, one of the company’s best actors (he played Tolstoy in The Passing of the Great Old Man) also left to fight, and was killed in action. Several months later, in April 1915, unsatisfied with their inadequate compensation, Gardin and Protazanov turned in their resignations (“Khronika” [April 4, 1915]). One month later, Paul Thiemann, who was a German subject, was exiled to Ufa, a small city in the Asian part of Russia (Deriabin et al. 178). He continued to work remotely while the Moscow office was run by Elizaveta, with certain assistance from her father Vladimir Mickwitz. It seemed that the whole business was falling apart. It was then that Elizaveta started negotiations with the director Vsevolod Meyerhold, a key figure in the history of twentieth-century theater. The outcome of these negotiations was The Picture of Dorian Gray (1915), based on Oscar Wilde’s novel, which not only helped to save the company, but also became one of the most significant films in the history of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema.

Advertisement for The Picture of Dorian Gray (1915) directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold, Sine-Fono no. 18 (1915).

The film is considered lost, but reviews and memoirs show that it was a unique example of a literary adaptation that truly interpreted the original text rather than just illustrating it. Particular attention was paid to the film’s visual style, which belonged to a symbolic rather than realistic mode (Kovalova 69-74). Elizaveta’s involvement in this project is extensively described in Levitskii’s memoirs. Among other things, he mentions that it was she who came up with the idea of having a woman play Dorian Gray and suggested Varvara Yanova for the part (Levitskii 87).

At the end of 1915, the company announced a particularly challenging project of adapting two canonical texts of Russian literature (both in verse): Alexander Griboedov’s comedy Woe from Wit and Alexander Pushkin’s novel Eugene Onegin (“Khronika” [December 19, 1915]; “Khronika” [January 15, 1916]). Both productions were highly anticipated; however, they were “frozen” in the summer of 1916. One possible explanation for this can be found in the memoirs of cinematographer Yuri Zheliabuzhskii. According to him:

In the summer of 1916, there was a falling out between E. V. Thiemann and the leading staff of the atelier. Thiemann himself was in exile, as a German subject. His wife was a rather quarrelsome woman and, besides, had a lack of taste. In reality, business was run by the five consisting of the leading director and manager [Aleksandr] Volkov, director [Aleksandr] Uralskii, head of the screenwriting department [Vitold] Akhramovich, actress and administrator [Evgeniia] Uvarova. E. V. Thiemann started writing to her husband that she is being pushed into the background, people are pressing their tastes upon her. In response to this, not seeing the actual state of affairs from his exile, Thiemann decided to manage blindly. As a result, all of us, except for Uralskii, left Thiemann. (Zheliabuzhskii 182)

This recollection cannot be completely accurate. Elizaveta could not have sent Paul such a letter in the summer of 1916 because she herself was forced to leave Moscow on May 23 of that year to join him in Ufa (Deriabin et al. 202). In the following two years, Thiemann’s company (which changed its name to Era) was able to produce a number of aesthetically challenging films (including Meyerhold’s The Strong Man [1917]). However, this new “poetic” period for the company (and, more generally, in Russian film adaptations) fell victim to either these disagreements within the studio or simply to Elizaveta’s forced departure.

The Thiemanns must have returned to Moscow after the February Revolution of 1917. Half a year later, soon after the October Revolution, Paul Thiemann announced his decision to leave Russia and set up a film company abroad (“Khronika” [1918]). He did produce a number of films in France in the early 1920s before settling down in Germany. While researching his émigré career, film scholar Rashit Yangirov came across what he thought was an obituary of Elizaveta’s younger sister Lydia, published in March 1926 (Yangirov 282). In reality, the obituary referred to Elizaveta’s mother, whose name was also Lydia. But somehow the confusion spread even further, and now, in a number of sources, such as Viktor Korotkii’s fine guide to early Russian film directors and cameramen, 1926 is wrongly provided as the date of Elizaveta’s death (Korotkii 364).

Yet the fact that, in the 1920s, Elizaveta was quite alive is confirmed by Natalia Noussinova’s important book on the history of the Russian émigré cinema. Noussinova cites a business letter from the cameraman Nikolai Rudakov to the producer Alexandre Kamenka, dated November 14, 1931, in which a new cinema enterprise organized by Elizaveta Thiemann is discussed (Noussinova 89-90). This venture most likely failed, otherwise we would know more about it. Life in Europe for the Thiemanns was rather chaotic, and full of financial problems, bumps in the road, and twists of various kinds. Both Thiemanns and Vladimir Mickwitz continued to associate themselves with cinema as long as they could. When Meyerhold visited France in 1928, he received several letters from Mickwitz, who tried to persuade him to renew his cooperation with Thiemann (Minckwitz). In 1941, Elizaveta and Paul divorced, but they had separated long before that, around 1933 (G. Thiemann 2).

It was because of Lydia the younger that we were able to track the later years of Elizaveta’s life. Lydia was married to Jimmy Winkfield, a legendary Thoroughbred jockey and horse trainer. In Winkfield’s biography, written by Ed Hotaling, Elizaveta is described in a somewhat ironical manner: “Beautiful and more than a bit eccentric, Elizabeth costarred at the Thiemann’s large estate, with fourteen servants, a monkey who had the run of the mansion, and a snake, a literal, living boa that Elizabeth wore around her neck at parties. She and Paul had a son and a daughter, who were apparently considered less amusing than the pets” (Hotaling 148-149). Hotaling was mainly relying upon the recollections of Elizaveta’s son Yuri (later George) Thiemann (1925-2018).

Jeannette Thiemann, George’s widow, generously shared with us a collection of family photos, letters, and stories. Unfortunately, there is practically nothing about Elizaveta’s work in cinema and not much about her later years. She was rather detached from her family. Soon after the separation with Paul, she sent both of her children away to be cared for by their aunt Lydia. “In 1941,” George recalls in an unpublished text, “my mother lived in Turin, Italy. One day she ‘remembered’ she had a son in France and sent for me. […] I was a minor and I had to follow my mother’s wishes. My mother and I lived there for a few months. Since it was too cold in Turin, she decided to move to San Remo, in the Italian Riviera. I started to work to support the two of us. My mother refused to work because it was too humiliating for her” (G. Thiemann 2). George worked as a waiter and bartender in a hotel, and later as an interpreter for the American troops with a side job as a night watchman (2-3). In 1954, he got married and two years later moved to the United States. Soon his first child was born, and he was no longer able to support his mother. Enraged, she tried to sue him. This did not improve their relationship, which was already somewhat tense (J. Thiemann).

Elizaveta stayed in San Remo until the end of her life. Some of her letters to George from the 1950s and 1960s survive. They are full of ellipses and exclamation marks and mainly consist of complaints and accusations: “I have to save my life from this barracks at any cost. Another winter like this—I’d rather die” (E. Thiemann [June 14, 1951]); “I want to scream till death like an abandoned dog” (E. Thiemann [December 18, 1956]); and “The solitude kills me: weeks without exchanging a word” (E. Thiemann [June 27, 1964]). Time and again, she wrote about suicide. She did not kill herself, however. She died sometime in the late 1970s, approaching the age of ninety. The family was informed of her death via a letter from a local priest. Now that letter is lost, and the exact date of Elizaveta’s death remains unknown (J. Thiemann).

Elizaveta Thiemann’s letter to George Thiemann from August 20, 1964 (in French). Courtesy of the Thiemann Family Archive.

“She never worked a day in her life,” her son repeated on multiple occasions. And it looks like she did not—in his lifetime. Was it the misfortunes of a nomad life, isolation from the culture she knew, vain attempts to relaunch her film business in Europe, or simply the approaching old age that changed one of the most active people in the Russian film industry into a permanently discontent hysterical woman? Hopefully, now we can understand better that Elizaveta’s short filmography does not at all reflect her true participation in pre-revolutionary Russian film culture. As we continue to unearth more about early Russian cinema, the significance of Elizaveta Thiemann’s contributions as a director and producer will likely only grow.

See also: Natalia Bakhareva

The authors would like to express heartfelt gratitude to Arina Ranneva and Aleksandr Sobolev for their kind and open-handed help in this research. They authors are also deeply indebted to Jeanette Thiemann and Cynthia Stegman for the priceless family documents and photos that they have generously shared as well as for their support.