A native of Hoboken, New Jersey, Emily S. McCain was already forty years old when she started publishing short stories in newspapers and magazines under the pen name Elizabeth R. Carpenter. Shortly afterward, she ventured into the field of screenwriting, where she established herself as a successful independent freelancer. By the mid-1910s, “Elizabeth R. Carpenter” was a prominent author at the peak of her career, and a celebrated figure in the burgeoning film industry. Sometimes also credited as E. R. Carpenter, she sold scenarios to major studios like Vitagraph, Edison, Kalem, and Lubin, and left behind a trail of praise in the early film press. But, despite her literary achievements, McCain kept her real identity well concealed, to the point that specialized film trade outlets, as well as film historians in the following decades, never referred to Carpenter by any other name or seemed aware that this was a pseudonym. Carpenter disappeared suddenly from the industry and press around 1919, leaving behind few clues about her life and identity. Putting a name to the person behind Carpenter has been possible only after the extensive research undertaken for this profile, which represents the first effort to shed light on the screenwriter’s real identity.

The possibility of Elizabeth R. Carpenter being a pseudonym came up as a result of researching an address that frequently appeared next to her name in early press publications: 723 Washington Street, in Hoboken. Examination of censuses, directories, and other primary sources yielded no connection between this address and any woman named Elizabeth R. Carpenter, but instead revealed a consistent association with three sisters: Nellie, Winifred, and Emily McCain. Numerous sources show the McCain sisters residing on Washington Street between the early 1890s and the late 1910s, a period that overlaps with Carpenter’s active years. This discovery reformulated my investigation by introducing a new dilemma about Carpenter’s identity: which one of the McCain sisters was the author?

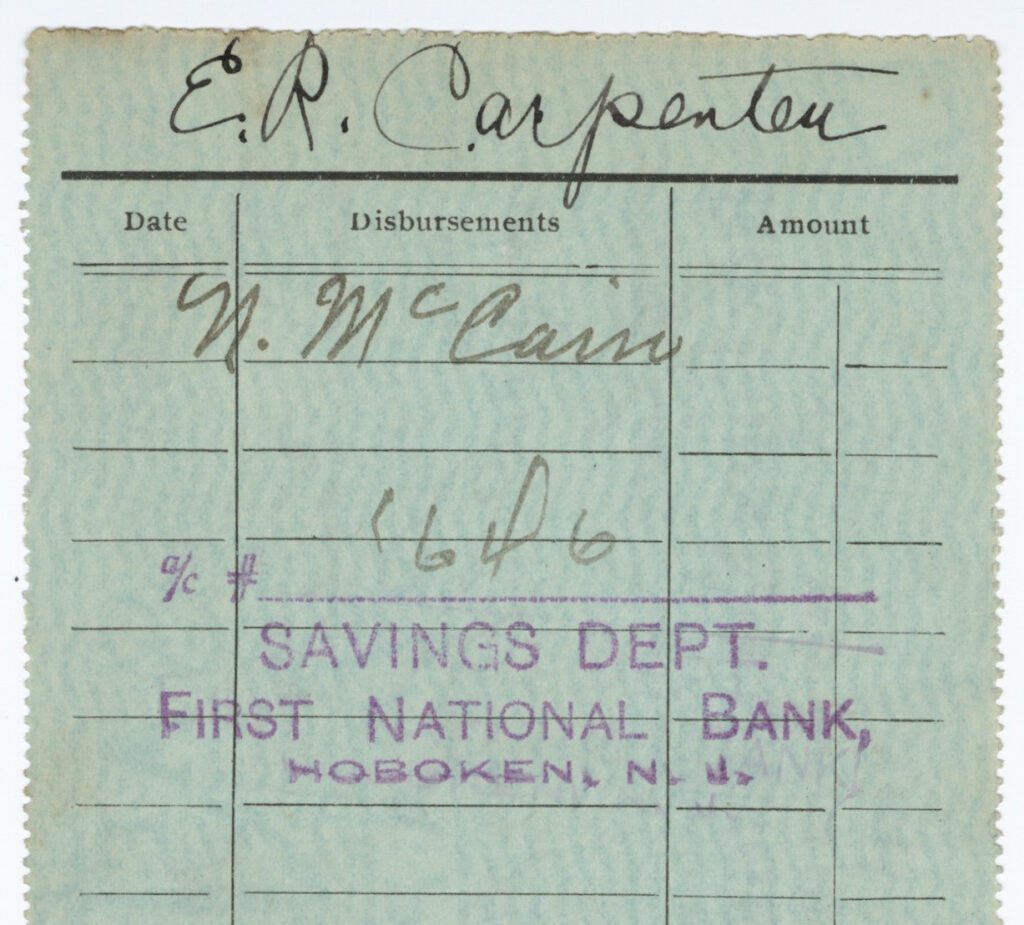

Detail of bank receipt signed with the names E. R. Carpenter and N. McCain. Courtesy of the Cinémathèque française.

Two pieces of evidence initially directed the investigation toward Nellie McCain. First, there was the discovery of a bank receipt inscribed with the name N. McCain, attached to a contractual document signed by Carpenter in 1912. This document reflects the sale of a script titled “A Chase for a Fairy” to the Majestic Motion Picture Company and is one of four contracts signed by Carpenter preserved in the Triangle Film Corporation/Harry E. Aitken collection at the Cinémathèque française. Nellie’s involvement in literary activities was further confirmed by the inclusion of her name among the non-winning participants in the writing competition “Advice for the Heart Hungry,” publicized in the press in 1913 (“S. Anargyros Announces”).

At this point in my research, Nellie McCain seemed to be the most plausible option, and the question of her identity might not have progressed any further if not for another, late-stage, discovery: a December 1910 article in the regional Jersey Observer documenting Emily McCain’s literary beginnings and her direct connection with the Carpenter name:

To-morrow [sic] the Observer will publish a short Christmas story from the pen of a young woman resident of Hoboken. The writer of this little story is Miss Emily S. McCain and her pen name is Elizabeth R. Carpenter. […] Miss McCain began writing short stories and occasional poetry only about a year ago and so far has been quite successful, for a new writer, and is gradually finding a more ready market for her productions. (“To Publish Story”)

Press article profiling up-and-coming writer Emily S. McCain. Jersey Observer (23 December 1910): 3.

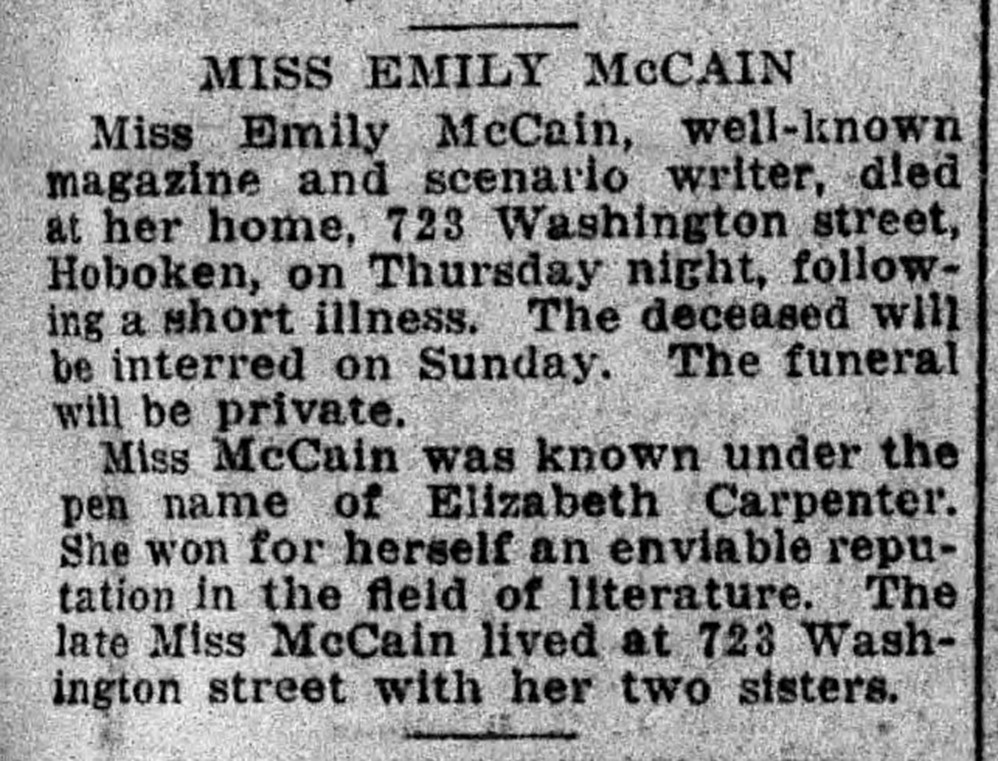

An additional finding came to support this connection to the youngest sister. In November 1918, an obituary for Emily McCain was published by the Hudson Observer, noting her reputation under the pen name of Elizabeth R. Carpenter (“Miss Emily McCain”). The confirmation of Emily’s death in 1918 also provided an explanation for Carpenter’s sudden disappearance before the end of the decade, for which no solid explanation was previously available. At this stage, the extent of Nellie McCain’s involvement in the Elizabeth R. Carpenter’s venture remains uncertain, but sources like the bank receipt at the Cinémathèque leave the door open for speculation about the possibility of a collaborative effort between the McCain sisters.

Emily McCain’s life developed quietly until her publishing breakthrough. She was born into a middle-class, socially connected family. The McCains were active in several Christian philanthropic groups that operated in association with Hoboken’s First Methodist Church. Along with her mother and sisters, Emily was an active presence at the town’s social gatherings and charity events, offering violin recitals (“For Hoboken’s Poor”) or participating in broom and dumb bell drills, popular gymnastic routines that incorporated props (“Among the Churches”). The family was also strongly involved in the editorial field. Emily’s father, Samuel McCain, worked as a bookbinder, and several of her brothers pursued careers in journalism and publishing. Following in the footsteps of Nellie and Winifred, Emily became a schoolteacher, after earning several specialized degrees in sewing instruction. In 1889, she received a special certificate of capacity from the New York College for the Training of Teachers (later, Teachers College) (“Instructing Women”). In 1893, she obtained a graduate degree from the Pratt Institute (“Six Classes Graduate”). From 1894 to 1901, she worked as a sewing instructor in schools in Brooklyn and Hoboken, although she had to step down from her position on at least one occasion due to health problems (Rue). In the following decade, censuses and directories often listed her as unemployed or without a specified occupation.

Hoboken address accompanying the publication of “The Dean’s Checkmate,” next to Carpenter’s name. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The earliest known short story credited to Carpenter, “The Dean’s Checkmate,” won the New York Evening Telegram’s weekly Prize Story Contest in January 1910. Other stories appeared in publications aimed at a children’s audience, such as the mail-order magazine Comfort, and the periodical Everyland, which billed itself as “a magazine of world friendship for girls and boys.” While it is reasonable to assume a transition from this literary pursuit to the craft of screen stories, Carpenter appears to have carried out both activities in the early 1910s. Even as late as 1915, with her screenwriting career well established, Comfort published a short piece, “Who Says Friday is an Unlucky Day?” credited to E. R. Carpenter.

Between 1913 and 1914, the name E. R. Carpenter appeared in the press regularly in association with film stories she sent to the Photoplay Clearing House, an organization that revised and sold scripts to production companies on behalf of authors. The Photoplay Clearing House referred to Carpenter as “a successful playwright who has sold many scripts” (“Send Us Your Scenarios”) and Carpenter’s letters of gratitude were regularly transcribed by them. These communications reveal she was working on three scripts during this period entitled “The Sword of Damocles,” “Judge Not,” and “Peter Grey,” although no released films under those titles have been located (“Rejected Photoplays”). In 1913, she also took part in the Motion Picture Story Magazine photoplay writing contest “The Diamond Mystery.” Although she did not win the award of a Vitagraph adaptation, she received an honorable mention along with other “contestants whose work was exceedingly good” (“The Great Mystery Play”).

By the time Carpenter was linked to the Photoplay Clearing House, she had already successfully sold several scenarios to the Majestic and Reliance companies, something evidenced by the four contractual documents signed by E. R. Carpenter and held at the Cinémathèque française. In addition to the already mentioned contract for the sale of “A Chase for a Fairy,” the other three records consist of contract documents addressed to the Carlton Motion Picture Laboratories in New York. They correspond to the sale of three scenarios: “Fairly Caught,” (c. 1913), “Turning of the Tide” (the back of document is stamped as received on January 10, 1913), and “Blue Lightning Sapphire” (date unknown, probably 1913). It is uncertain, however, if any of these scenarios ever made it to the production stage, a question to which I return in the Credit Report.

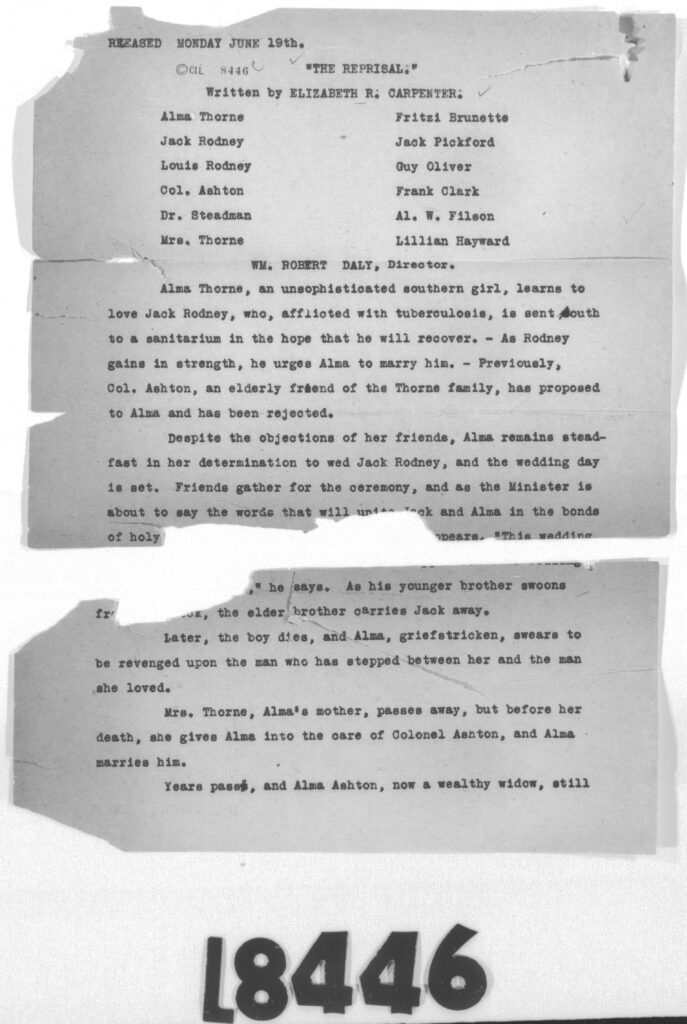

First page of the copyright description for The Reprisal (1916). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The earliest mentions of released films that can be undoubtedly credited to Carpenter come from late 1913. The release of The Disguise, an intricate melodrama featuring false identities, stolen jewels, and a star-crossed romance, was announced by several press sources in September, with Carpenter credited as the author. In connection with this notice, Reel Life listed Carpenter next to other “writers of reputation entering the moving picture field” (“Experienced Authors”). It is also verifiable that Carpenter was the author behind a film entitled The Reprisal that had been written as early as October 1913, when the Photoplay Clearing House reported that they had sold a script under this name to Kalem on behalf of E. R. Carpenter (“Plant Your Play Here”). No further information has been found about a Kalem release under this title, but, in 1916, Moving Picture World announced the release of a Selig short film also titled The Reprisal, with Elizabeth R. Carpenter credited as screenwriter (“The Reprisal”).

Elizabeth R. Carpenter advertises herself as a photoplaywright, next to the titles of her most two recent releases in the New York Dramatic Mirror (23 September 1914): 32.

The year 1914 marked the beginning of Carpenter’s most widely celebrated and best-documented period. Together with 1915, it was her most prolific year, and references to her scenarios can be found both in the press and in copyright catalogs. Between 1914 and 1915, William Lord Wright mentioned Carpenter three times in his column, “For Photoplay Authors, Real and Near,” in the New York Dramatic Mirror, giving us rare access to the writer’s thoughts and views. In July 1914, he transcribed an enthusiastic letter sent by Carpenter to the newspaper:

I’m writing only synopses at present, having discovered to my surprise that they bring as much as finished one-reel scripts. Time was when I felt quite proud at receiving $25 or $30 for a single-reel story, but Vitagraph is paying me that for brief synopses. The company has now taken quite a number. I’ve been writing two years now, but not entirely photoplays. Many of my stories and other odds and ends have been published in magazines and elsewhere. The reason I am doing synopses is that I have so little time to give to photoplay writing, and then editors seem to think we are poor in technique. But as you say, “practise [sic] makes perfect” and Vitagraph has never criticized my construction. My “Widow of Red Rock” was at Vitagraph Theater recently, and, best of all, my name appeared on posters in connection with my play. (“Selling By Synopsis”)

In September 1914, the column described Carpenter’s winning of a Vitagraph contest prize with a multiple-reel photoplay and how her work had been praised by Kalem’s editor Phil Lang. Lord Wright also mentioned that six of her submissions had been produced by Vitagraph since that past spring and emphasized that only two of them originated from synopses (“The Hall of Fame”).

In April 1915, Carpenter candidly elaborated on her trajectory and her current standpoint, through a new transcribed letter:

I have sold on an average more than three scripts a month during the past year. I am feeling very happy for it seems to me that I have really become a photoplaywright, not near, but real! You have said sometimes: “Keep at it, you will get there” and I believe you will now admit that I am there. Eighteen sold the past year were to Vitagraph and the others have been taken by Lubin, Edison, Biograph, American and Gaumont. I am resting a little now but I shall soon begin on the photoplays with renewed zest. I love the work. It seems very wonderful to me to think I have the power to create these plots, to keep it up day after day, and to be suiting first-class companies. (“She Writes Synopses”)

On these remarks, Lord Wright observed: “A year ago Miss Carpenter was discouraged. She was informed that just everyday synopses were not wanted by any company. We informed her that if she could furnish original ideas she would arrive. During the past year she has been selling nearly one idea a week.”

However, this approach also attracted some criticism. Just a month later, in his Moving Picture World column “The Photoplaywright,” critic Epes Winthrop Sargent directly criticized Carpenter’s letters, her focus on exclusively writing and selling synopses, and the encouragement received from Lord Wright (“Synopses”). While the habit of selling brief plot synopses instead of fully formed scenarios had been common at the time the industry was undergoing consolidation, it is clear that, by this point, the respectability of this practice was strongly disputed.

But despite her self-confessed habit of selling synopses, Carpenter’s preserved scripts do reveal a complete and structured layout. December 1914 saw the publication of the screenwriting manual How to Write a Photoplay by Arthur Winfield Thomas, which transcribed the entirety of Carpenter’s script for the film Fogg’s Millions (1914). Her work was introduced as a model of good craftsmanship for multi-reel picture plays. This document proves highly valuable not only because Fogg’s Millions is a lost film but also because it illustrates the complexities of screenwriting work at that historical point (Thomas 175-189).

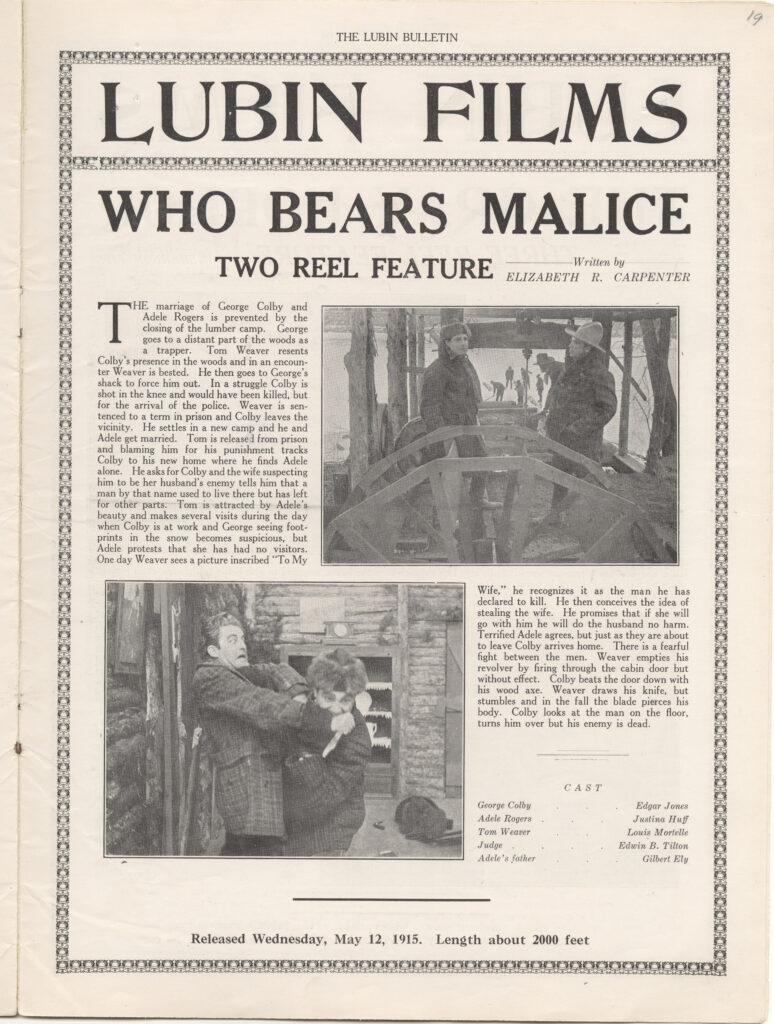

Advertisement for Who Bears Malice (1915) in the Lubin Bulletin (17 May 1915): 19. Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Preserved primary sources like original scripts and published synopses in the press also offer significant insights into the narratives that Carpenter specialized in. The majority of her stories fall into the domain of melodrama, with an emphasis on romance and moral conflicts. Recurring themes include endangered marriages or star-crossed lovers, lurking danger, kidnappings, monetary greed, or jealousy as plot-driving forces. Notable exceptions are Rooney’s Sad Case (1915) and Jane’s Husband (1916), which dabble in a lighter, comedic tone. Another example of Carpenter’s recurring narratives, the lost film Who Bears Malice (1915), featured a married couple whose lives are disrupted by the villain’s determination to take revenge on the lumberjack husband for causing his past incarceration, a conflict that concludes with the villain’s death.

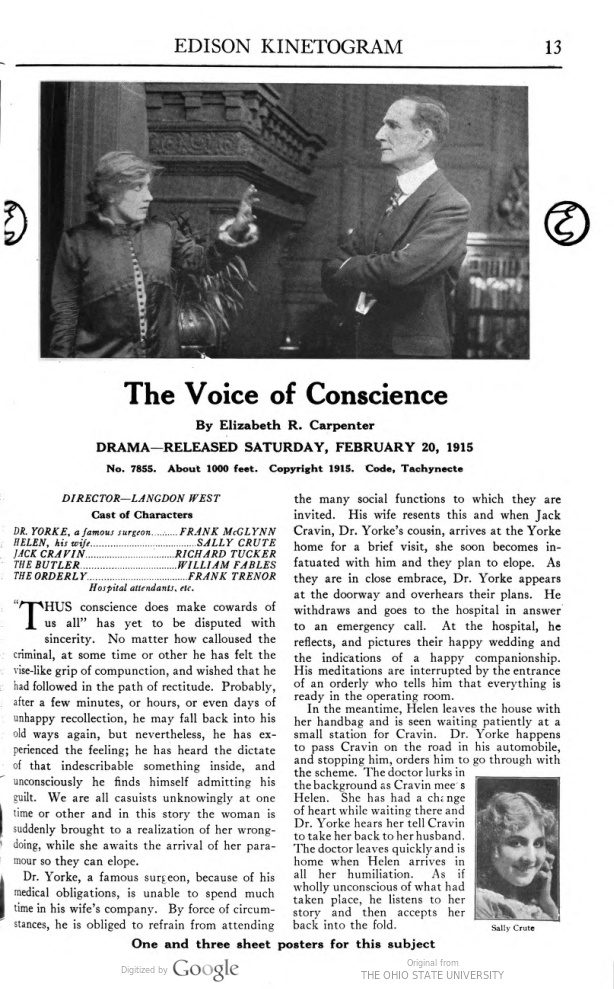

Only five of the several dozen films attributed to Carpenter are extant today. The 1915 films Her Husband’s Son and The Voice of Conscience have been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art as pre-print elements, 35mm fine grain masters. MoMA also holds original script materials and promotional images from these titles. Both films deal with married couples confronted with the risk of separation due to societal conflicts. Two other extant films, John Rance, Gentleman (1914), preserved in a private collection, and Behind the Veil (1916), held by the Deutsche Kinemathek, depict frivolous women facing retribution after trying to achieve their goals through manipulation and deception.

Carpenter’s fifth extant film, The Good in the Worst of Us (1915), is preserved at Eye Filmmuseum and the British Film Institute. It was screened in 2021 as part of the Women Screenwriters of American Silent Films program at the Giornate del Cinema Muto, in Pordenone, allowing Carpenter’s work to reconnect with contemporary audiences, as well as placing it in relation to other women screenwriters of the era. The story of a married woman whose happiness comes under threat when someone from her criminal past reappears, the film reflects the melodramatic mode in which Carpenter worked. A nitrate print of The Test of Chivalry (1916) was held by UCLA until 2008, when it was declared lost to deterioration. The film is, therefore, considered non-extant.

Carpenter’s success lasted through 1916. At least six films released that year can be solidly credited to her, and in July, Winthrop Sargent expressed a more positive view of the writer, referring to her as one of Lubin’s most valued freelance bookers, or “standbys” (“Another ‘Stolen’ Story”). However, 1916 also marked the beginning of a decline in the number of releases linked to Carpenter’s name, with only one known film credited to her in 1917, Mary from America (“Mary From America”). This may be related to another writing activity that occupied Carpenter’s time in 1917, the completion of several pedagogical plays about major historical figures. Intended as a tool for Hoboken’s teachers and conceived expressly to be performed by schoolchildren at yearly festivities such as Christmas or Thanksgiving, this work attests to Emily McCain’s commitment to her hometown, and to harnessing literary creativity in the service of pedagogy (“Pupils’ Dramas”).

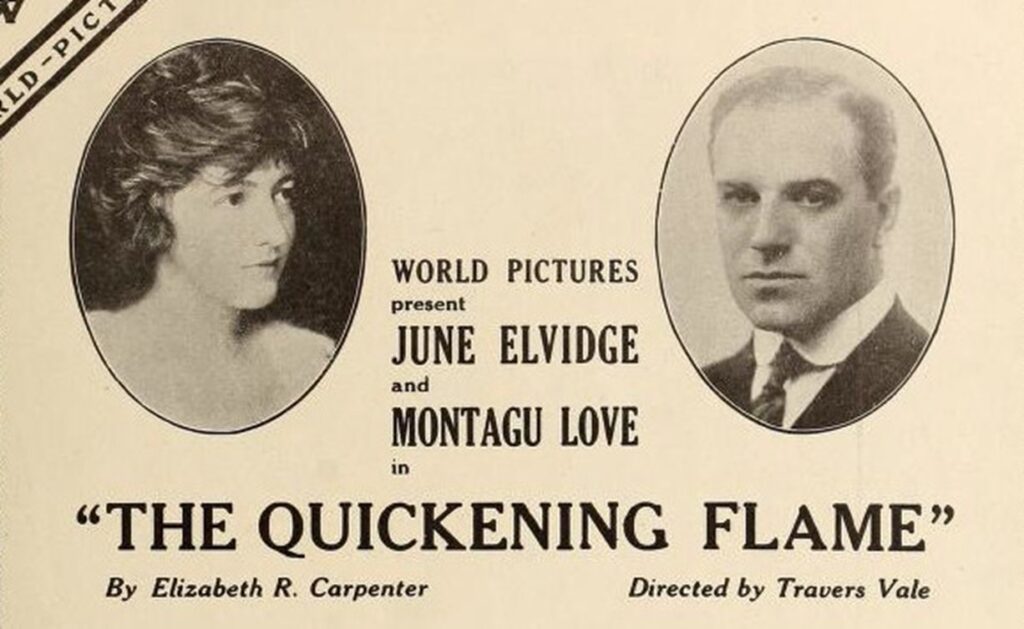

Detail of an advertisement for The Quickening Flame (1919) featuring Carpenter’s name in Motion Picture News (26 April 1919): 2603.

On June 22, 1918, Moving Picture World reported on the recent purchase of rights to Elizabeth R. Carpenter’s original story “The Quickening Flame” by World Pictures. The publication added that Carpenter was “a well-known writer” whose works had been “interpreted in motion pictures by the leading screen stars” (“Three Big Writers”). The Quickening Flame was not released until April 1919, a date that Emily McCain unfortunately did not live to see. Following a short illness, she passed away suddenly in November 1918, in the same house she had lived for most of her adult life with her two sisters, and where she had become Elizabeth R. Carpenter. After this posthumous release, media references to Carpenter soon halted, relegating her to obscurity for more than a century. Emily was buried in the McCain family plot at New York Bay Cemetery, later alongside Nellie and Winifred, who passed away in 1926 and 1946, respectively.

McCain family gravestone in the New York Bay Cemetery. Courtesy of James Cox of the Hoboken Public Library.

By the time Elizabeth R. Carpenter became a household name, the McCain sisters were all over forty, with Nellie, the eldest, being in her fifties. Emily McCain’s age, and her prolonged use of a pseudonym, challenge the patterns often assumed about women screenwriters of the silent era, many of whom pushed the boundaries of recognition as ambitious, younger women with public profiles. However, McCain’s case is not entirely unheard-of, as it evokes examples of women like Lillian Ducey, who began a late screenwriting career after participating in a short-story contest held by the New York Evening Telegram.

The three McCain sisters also never married nor had children, a position that inevitably singled them out as spinsters. Lodging with other women and working in elementary education were common ways to counteract the economic and social impact of extended female singleness. But this domestic position is not entirely at odds with the reality of authorial labor in the early film industry. Freelancing women authors had been a mainstay of popular magazine publishing since the nineteenth century, as it was an activity suited to being developed from within domestic spaces. For women who needed to circumvent gender or class barriers or who couldn’t afford to sacrifice their social stability, this was a great opportunity. This trend later carried over to the film industry, as explained by Donna Casella’s WFPP overview essay “Shaping the Craft of Screenwriting: Women Screen Writers in Silent Era Hollywood.” During the early 1910s, the press played a crucial role in connecting authors with studios and facilitating their constant supply of ideas, through advertisements, promotional campaigns, or contests. A large percentage of these literary contributions came from women who wrote from home. Motivated by creative ambitions and a desire for economic independence, they contributed extensively to the screenwriting field, which encompassed not just the writing of source stories but also adaptation, original scenario crafting, and continuity work. As Casella points out, the high number of scripts that audience members regularly submitted to scenario departments points to the existence of an extensive workforce of freelance authors that fit into what Wendy Holliday has called “the professional amateur.” The number of women contributing source material to the screen from their homes may have been high enough to warrant further investigation, something that is particularly important when it comes to those who have not been regarded as driving forces in the industry, such as elderly women, working women, or women who occupied the position of household heads. The use of pseudonyms may complicate this work considerably, but it also offers a very interesting opportunity for approaching the development of creative identities at the intersection of amateur writing and social class.

In closing, Elizabeth R. Carpenter’s career can be taken as exemplifying the evolution of women’s screenwriting labor throughout the 1910s, especially in relation to amateur and freelance work. Beyond speculation about the degree to which Nellie or Winifred McCain might have been involved in the Elizabeth R. Carpenter project alongside their sister Emily, it is clear that Carpenter’s writing activity grew out of a domestic space as an amateur enterprise, and was nurtured by a network of popular media that encouraged women with creative inclinations to direct their efforts toward the film industry, to the point that screenwriting eventually became codified as a woman’s job.

With additional research by Olivia Hărşan and John Jacobsen.

See also: “Shaping the Craft of Screenwriting: Women Screen Writers in Silent Era Hollywood”

This profile began as an expansion of earlier research on Elizabeth R. Carpenter, conducted by Olivia Hărşan, John Jacobsen, and María Hernández Ordeig for the Giornate del Cinema Muto 2021 catalog. The author would like to thank all the archives that assisted in making this research possible, as well as the McCain family descendants and all the people of Hoboken who advised her attempts to locate photographs of the McCain sisters.