Like many other early Russian film actors, Ol’ga Rakhmanova entered into a new career after a long professional life in theater, mostly in the provinces. She was born in Odessa, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, sometime in 1871 and studied there at the Drama School of the Russian Music Society. Abandoning her married name, Sokolova, and her three children, she first acted in semi-amateur troupes. In 1896, as the first Lumière films were shown in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, she made her professional stage debut under the guidance of a well-known provincial entrepreneur, Konstantin Nezlobin, in Vilna, now Vilnius, Lithuania. However, it would take her almost twenty years to branch out into cinema.

During those two decades, Rakhmanova worked as an actress, a theater director, and entrepreneur in various towns of the Russian Empire. In 1905 or 1906, in her hometown of Odessa, she opened declamation and elocution classes, which were later transformed into a theater school. In the 1910s she moved to Moscow, where she worked in the popular Drama Theater of V. Sukhodol’skii, whose company included most of the screen stars of the time, among them Vera Iureneva, Vladimir Maksimov, and Ivan Mozzhukhin (Mosjoukine). It is not surprising, then, that in 1915, Rakhmanova also made her screen debut–in Petr Chardynin’s sensational drama Mar’ia Lus’eva. After that, she mostly worked at Aleksandr Khanzhonkov’s studio, playing mothers of suffering young heroines, and occasionally aunts of heroes. Most famously, she was the merchant step-mother of Vera Kholodnaia in Evgenii Bauer’s A Life for a Life (1916), who shot her son-in-law in a dramatic finale. In a May 15, 1916 review of that film in Teatral’naia gazeta, Rakhmanova was acknowledged as “a wonderful grande dame” of Russian cinema (16).

In 1916 Rakhmanova’s first script was directed by Bauer himself. Only What’s Lost is Forever told the story of the tragic rupture between an artist and his family and friends, who are unable to understand his creative aspirations. Together with most of Khanzhonkov’s cast and crew Rakhmanova went to Crimea in the summer of 1917 for the annual location shoots. When Bauer suddenly died at the very beginning of the trip, several of his films were left unfinished, including the adventure melodrama The King of Paris (1917). Since all the interior scenes for it had already been shot in Moscow, the film was finished on location by members of the cast and crew. In the restored version of the film, preserved at the Russian State Film Archive, Rakhmanova is listed as its co-writer and co-director together with Bauer, which is also reflected in historical overviews of the period (e.g., Ginzburg 2007, 385). Some contemporary sources, however, stated that the film was finished by its cast headed by Emma Bauer, the director’s widow. At least, the studio’s head, Aleksandr Khanzhonkov, says as much in the unabridged, unpublished version of his memoirs, The First Years of Russian Film Industry, written in the mid-1930s and held at the Russian State Film Archive (310). Alternatively, Lev Kuleshov, who was the film’s art designer, claimed in his memoirs that he participated in the collective efforts to finish the film (1988, 43), and his participation has been recently more and more emphasized by scholars. Eventually, the new “restored” version of the film shown on Russian television in 2008 credited Kuleshov and Bauer, but left no mention of Rakhmanova.

This difficulty of attribution is characteristic of most of Rakhmanova’s output as a director. A simpler case is presented by her next film, The Tale of the Spring Breeze (1917). Although Ivan Perestiani, who played the main part, later claimed to have directed the film, an October 1918 article in Kino-gazeta clearly named Rakhmanova the film’s director (4). At the same time, a June 1918 article in Kino-gazeta called her next film, An Episode of Love (1918), her first work as a director (11). It had been, perhaps, begun before The Tale of the Spring Breeze, but completed and released later. Rakhmanova also wrote the script for An Episode of Love and, as usual, played the blind harpist mother of the heroine, Irina. The young version of her character in the film was played by Natal’ia Sokolova, who most likely was Rakhmanova’s own daughter. She had studied in her mother’s acting school in Odessa and also appeared in Rakhmanova’s next film, Faust (1918). One contemporary critic, going by the pseudonym “Ten,” had this to say about Rakhmanova’s work on An Episode of Love: “One feels that the new film director has a firm grip on her material, arranges mise-en-scènes clearly, and does not lose the action’s tempo. But the combination of author, actor, and director in one person hindered each of them individually” (1918, 9).

A publicity still for Only What’s Lost is Forever (1916) with Ol’ga Rakhmanova in Vestnik kinematografii.

In the last months of private film production in Russia, Rakhmanova wrote and directed an adaptation of Ivan Turgenev’s short story, Faust. Because of the absence of positive stock and electricity to power film theaters, the film was never released. In August 1919, in the atmosphere of diminishing opportunities for practical filmmaking, another former director of the Khanzhonkov studio, Boris Chaikovskii, organized a private film school called “Tvorchestvo,” which translates to “Creation,” with Rakhmanova as one of the main teachers. He was also behind her return to cinema, first as an actress. In 1920 Chaikovskii made two short agitation films, It Shouldn’t Be This Way, and On Peasant’s Land; in both of which he employed Rakhmanova.

Never quite leaving the stage, in 1921 Rakhmanova became the director of the newly-formed drama workshop/studio at the Moscow Military Sanitation Administration. It was created to promote sanitation education through “show trials,” for example, of prostitutes, as well as through performances of classical plays such as Ibsen’s “Ghosts.” Additionally, new works under the titles such as “Stigmatized by Shame” and “The Victim of Dirt” were performed (Wood 2005, 111-12).

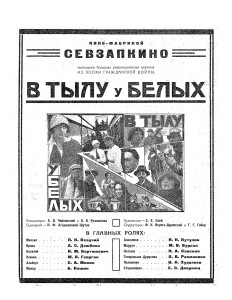

In the mid-1920s Rakhmanova continued teaching acting at Chaikovskii’s film school and took part in the production of his new film, Behind White Lines (1925), written by Nina Agadzhanova-Shutko. The cast included several of their students, and Rakhmanova herself played the wife of General Durasov. When Chaikovskii suddenly died of a brain hemorrhage in November 1924, she again finished the film. In this case, unlike the Bauer controversy, her own account of how much was done by each co-director survives. Rakhmanova’s slim personal file, held in the collection of the Union of Drama Writers and Composers at the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts, includes a statement that asserts that Chaikovskii had done all the outdoor scenes and had drafted the plan of the rest. After his death, Rakhmanova shot interior scenes and edited the film together with Agadzhanova-Shutko and Petr Malakhov. For the purposes of protecting her author’s rights, she concluded: “I think that half of the work was done by B.V. Chaikovskii and the other half by me” (8).

Rakhmanova’s obituary of Chaikovskii is the closest one finds to her own director’s creed. Dividing Russian directors into two “schools” according to the role they delegate to human beings on screen, Chaikovskii (and Rakhmanova with him) proclaimed man

the center of a film shot, its main part. All the other shots are supplementary. They don’t have intrinsic value on their own. Nature, sets, lighting, props–all this is only a background, elements needed to strengthen the general impression, and nothing else. Man with all his inner essence, with all his multifaceted alternation of feelings is the primary great force of cinema, the reason for its unprecedented influence on viewers (Rakhmanova 1924, 7).

In September 1925 Rakhmanova started making a film called Why? at the Proletkino film studio in Moscow. It was a semi-educational film, alternatively called Clap is a Woman’s Bane, about the dangers of venereal diseases and their improper treatment, possibly connected to her previous work for the Military Sanitation Administration theater workshop. For unknown reasons, however, the shooting was stopped after a couple of months and then continued by another director, Valerii Inkizhinov (of the future Storm Over Asia [1928] fame), and with a mostly new cast. The released film, renamed Payback (1926), again had Rakhmanova listed as a co-director, although it is very unlikely that any of the scenes shot by her crew made it into the finished film (Ryabchikova 2010, 390–92). This was her last attempt at directing. In 1926 she was expelled from the main professional organization of filmmakers, Association for Revolutionary Cinema, for “having nothing to do with Revolutionary cinema,” according to the “Minutes of the 8th Meeting,” which are held at the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (10).

When Chaikovskii’s school, which she headed after his death, was closed sometime after 1930, Rakhmanova retreated into teaching elocution in the main Moscow theater institute, GITIS. She primarily worked with “nationality classes,” teaching students from the republics of Latvia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, now Kyrgyzstan, and Chuvashia. According to her obituary, until her death, Rakhmanova continued working on a textbook for theater, in addition to the previously written book on the phonetics of speech, declamation, and acting (Filippov and Saricheva et al. 1944, 4). Neither was ever published.

See also: Nina Agadzhanova-Shutko