by

Victoria Duckett

Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre programme, 1900. Private Collection.

Sarah Bernhardt is the most famous actress of the late nineteenth century stage. Celebrated by an emerging and very vocal group of young female workers and artisans in her native Paris in the late 1860s and the 1870s called “les saradoteurs” (Rueff 1951, 48-49; Bernhardt 1923, 290), she went on to become the most popular actress of her generation in Europe, North America, and Australia. Attention has been paid to her “golden voice,” the clever ways she marketed and promoted herself, her pioneering patronage of artists such as Alphonse Mucha and René Lalique, and her capacity to be at once a successful actress, manager, and theatre director (Pronier 1942, 93; Musser 2013, 154-174; Stokes 1988, 16-30). Scant attention has been paid, however, to Bernhardt’s involvement and success in the early motion picture film industry, both in France and abroad. This is surprising. Indeed, she was among the first celebrities to engage with the motion picture, playing Hamlet in a one-minute film that formed part of Paul Decauville’s program for the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre at the Paris Exposition of 1900. The first feature film that she released–Camille (1911)–was promoted the following year by the French American Film Company in Moving Picture World as “Making New Records for Selling States Rights” (982-983). A subsequent advertisement in the same trade press claimed that the film was “The Fastest Seller Ever Offered State Right Buyers” (1088-1089). As many film historians know, Bernhardt’s Queen Elizabeth (1912) was the Famous Players Company’s first release in the U.S. It similarly enjoyed success, helping to open the market for legitimate motion picture exhibition in the U.S. Queen Elizabeth thereby provided audiences with their first experience of the longer-playing narrative feature film (Quinn 2001, 48).

Sarah Bernhardt in Hamlet (1900), a Phono- Cinema-Théâtre production. Courtesy of the Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Although cinema critics, cinéphiles, and scholars have critiqued her theatrical acting on film (Lindsay 2000, 108; Bowser 1990, 204-205; Abel 1994, 316), Bernhardt’s contribution to the nascent cinema was broad as it was profound. She appeared not only in roles that were familiar to the late nineteenth century stage (Camille and Queen Elizabeth) but in new and original contexts. Of the films that survive, we can see her in rare celebrity “home movie” footage in Bernhardt at Home (1915), a social problem film Jeanne Doré (1916), as well as in a propaganda film sponsored by the French Ministry of War seeking American involvement in World War I (Mothers of France, 1917). The only film that survives from the post-war period is a fragment of the death scene from Daniel (1920). This shows Bernhardt at the age of seventy-seven performing as a young bed-ridden man dying of morphine addiction. Daniel is testimony to Bernhardt’s fame as an actress who specialized in the performance of death. Like her previous films, it is also testimony to Bernhardt’s refusal to accept invisibility even when she was aged and infirm (her right leg had been amputated in 1915).

Queen Elizabeth (Sarah Bernhardt) dies on film. Queen Elizabeth (1912). Courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Bernhardt in her atelier, Sarah Bernhardt at Home (1915). Courtesy of the Filmarchiv Austria.

As an actress, Bernhardt was renowned for the innovative way she developed the spiral. She made this the structuring motif for theatrical action. We can see the spiral most obviously in the way she swivels to her death in Camille. We might argue, in this context, that Bernhardt incarnates the French art nouveau movement, bringing the signature tendril of this decorative art form to film. As Stephen W. Bush argued in the Moving Picture World in 1912, she accordingly made herself “more enduring than brass” (760). It would be remiss to separate the agency Bernhardt enjoyed as an actress literally shaping the meaning of her films from the making of the films themselves. Indeed, we need to ask: who directed theatrical action in her films? Who organized and framed the mise-en-scène, particularly since there are visual overlaps between photographs of Bernhardt’s stage productions and the mise-en-scène in some of her films? Finally, who modified the story of the original theatrical play for the screen? While directors such as André Calmettes, Henri Pouctal, Henri Desfontaines, Louis Mercanton, and René Hervil are (often jointly) credited with directing her films, and while Jean Richepin is famously credited for the screenplay of Mothers of France, we still need to determine the role that Bernhardt played as director and perhaps even manager, producer, and screenwriter of her own films. Indeed, it is inconceivable that a mature woman who was an actress, manager, director, and playwright on the live stage would relinquish creative control on film.

Bernhardt beseeching Paul Dubois’s Joan before the cathedral at Reims, Mothers of France (1917). Courtesy of Lobster Films.

Bernhardt spirals to her death, Camille (1911). Courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Of Bernhardt’s extant narrative films, only three are available on DVD. These are Camille, Queen Elizabeth, and Mothers of France. Although Hamlet (1900) was newly presented in color as part of the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre 35mm program organized by Laurent Mannoni at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, Pordenone, in 2012, it is still unavailable online. It features only as a black and white “bonus” on David Menefee’s Camille DVD. Of the narrative films commercially available, these often show intertitles and feature music that has been adapted and inserted according to the contemporary taste of the DVD producer. The more representative examples of Bernhardt’s films reside, therefore, in various film archives in Australia, Austria, France, and the United Kingdom. For example, the best and most complete copy of Camille is located in the National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra, Australia, and must be seen on location. This contains the first two scenes that are missing from all available DVDs. Lobster Films in Paris, France, has a copy of Mothers of France that shows some of the original tinting. The film also allows us to see, quite clearly, Bernhardt’s vision of Joan of Arc. This was an excerpt from Geraldine Farrar’s film Joan the Woman (1916) that Samuel Roxy Rothapfel inserted as a special effect into the film when it arrived in America through a process of double projection, according to Motography in 1917 (665-666). Lastly, Filmarchiv Austria holds the extant copy of the 1915 “home movie,” Sarah Bernhardt at Home. Fascinating for the support this footage gives the contention that Bernhardt was an astute manager of her own public image, it has yet to be made publicly available for further study.

A vision of Joan appears, Mothers of France (1917). Courtesy of Lobster Films.

Just as there is no single repository or archive that holds all of Bernhardt’s films, neither is there a library that centralizes materials about Bernhardt’s involvement in motion pictures. Trade press reviews and publicity for Bernhardt’s American releases–La Tosca (1908), Camille, Queen Elizabeth, An Actress’s Romance (1913), Jeanne Doré, and Mothers of France– provide insight into how Bernhardt’s films were exhibited and received in the U.S. We must thank Lantern as well as Domitor’s Media History Digital Library, for these online resources. For the first time, scholars have easy and ready access to publications that help us better understand Bernhardt’s U.S. reception.

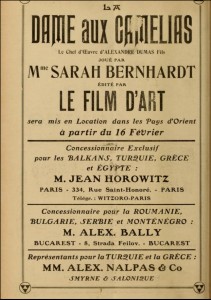

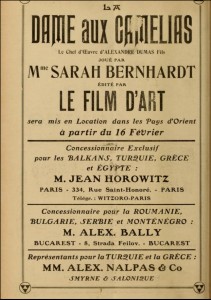

Advertisement for Camille (1911). Private Collection.

What, however, of Bernhardt’s reception elsewhere, in France or in any of the other countries across the globe that she vicariously toured as a “moving picture?” Online holdings for French film journals are sketchy, at best. Further, a January 27, 1912, advertisement for Camille in Ciné-journal advertises the film’s circulation in the Balkans, Turkey, Greece, Egypt, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and the Orient (32). How was the film marketed and received in these countries? How long was the film in theaters? Recent work on Asta Nielsen systematically scrutinizes her appearance and interpretation in local newspapers across the world providing an exemplary model of scholarship for the research yet to be conducted on Bernhardt’s distribution, exhibition, and marketing (Jung and Loiperdinger 2013). Bernhardt studies can follow Nielsen’s reassessment, which comes on the heels of research into the related histories of the Danish actress on both stage and screen. Our knowledge of Bernhardt’s contribution to the early film industry hinges as well upon scholarly consensus as to whether she was given or claimed the kind of agency as producer now attributed to Nielsen. For all the exhibition catalogues, publications, and biographies newly written about Bernhardt, she still needs to be explored as a celebrity who shaped theatrical film both locally and transnationally.

See also: Asta Nielsen

Bibliography

Abel, Richard. The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema, 1896-1914. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Bernhardt, Sarah. Ma Double Vie: Mémoires de Sarah Bernhardt. Paris: Eugène Fasquelle, 1923.

Bowser, Eileen. The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1990.

Bush, Stephen W. “Bernhardt and Rejane [sic] in Pictures.” Moving Picture World (2 March 1912): 760.

Ciné-journal (27 Jan. 1912): 32.

Duckett, Victoria. “The Actress-Manager and the Movies: Resolving the double life of Sarah Bernhardt.” Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film no. 45, vol. 1 (September 2018): 27-55.

------. “Celebrating transgressive celebrity: Sarah Bernhardt.” The Dangerous Women Project. The University of Edinburgh, The Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (9 June 2016): n.p. http://dangerouswomenproject.org/2016/06/09/sarah-bernhardt/

------. “Her Majesty Moves: Sarah Bernhardt, Queen Elizabeth, and the Development of Motion Pictures.” In The British Monarchy on Screen. Ed. Mandy Merck. Manchester: The University of Manchester Press, 2016. 111-131.

------. “Investigating an interval: Sarah Bernhardt, Hamlet, and the Paris Exposition of 1900.” In Reclaiming the Archive: Feminist Film History. Ed. Vicki Callahan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. 193-212.

------. “The Moving Pictures: Sarah Bernhardt and the Theatrical Film.” Cinegrafie 19 (2006): 314-326.

------. “A public precedent: Sarah Bernhardt, Gabrielle Réjane, and the early French double feature film.” L’Esprit Créateur vol. 58, no. 2, Special Issue, Femmes Créa(c)tives: Women’s Creativity in its Socio-Political Contexts (Spring 2018): 23-40.

------. “Sarah Bernhardt.” The Literary Encyclopedia. (06 August 2016): n.p. http://www.litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=391

------. Seeing Sarah Bernhardt: Performance and Silent Film. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

------. “The 'Voix d’Or' on Silent Film: The Case of Sarah Bernhardt.” In Researching Women in Silent Cinema: New Findings and Perspectives. Eds. Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett, and Lucia Tralli. Bologna: University of Bologna, 2013. 318-333. http://amsacta.unibo.it/3816/

------. “Who was Sarah Bernhardt? Negotiating Fact and Fiction.” Journal of Historical Biography 10 (Autumn 2011): 103-112.

“The Fastest Seller Ever Offered State Right Buyers.” Moving Picture World (23 March 1912): 1088-1089.

Jung, Uli, and Martin Loiperdinger, eds. Importing Asta Nielsen: The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. New Barnet, Herts: John Libbey, 2013.

Leveratto, Jean-Marc. “Sarah Bernhardt dans Queen Elizabeth (1912), du théâtre (français) au cinéma (américain).” In Théâtre, destin du cinema. Eds. Agathe Torti-Alcayaga and Christine Kheil. Paris: Le Manuscrit, 2013. 25-43.

Lindsay, Vachel. The Art of the Moving Picture. Ed. Martin Scorsese. New York: The Modern Library, 2000.

“Making New Records for Selling States Rights.” Moving Picture World (16 March 1912): 982-983.

Menefee, David. Sarah Bernhardt: Her Films, Her Recordings. Dallas, Texas: Menefee Publishing, 2012.

Musser, Charles. “Conversions and Convergences: Sarah Bernhardt in the Era of Technological Reproducibility, 1910–1913.” Film History vol. 25, no. 1-2 (2013): 154-174.

Ockman, Carol and Kenneth E. Silver, eds. Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005.

Pronier, Ernest. Une vie au théâtre: Sarah Bernhardt. Geneva: A. Jullien, 1942.

Quinn, Michael. “Distribution, the Transient Audience, and the Transition to the Feature Film.” Cinema Journal vol. 40, no. 2 (Winter 2001): 35-56.

Rueff, Suze. I Knew Sarah Bernhardt. London: Frederick Muller Ltd., 1951.

“'Split Reel' Notes for the Theatre Men.” Motography (31 March 1917): 665-666.

Stokes, John. “Sarah Bernhardt.” In John Stokes, Michael R. Booth and Susan Bassnett, Bernhardt, Terry, Duse: The actress in her time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. 13-64.

Archival Paper Collections:

Sarah Bernhardt clippings file. Museum of Modern Art, Film Study Center

Sarah Bernhardt Collection. University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center.

Sarah Bernhardt letters. New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Various archival materials relating to Bernhardt. State Library New South Wales, Michell Library.

An assortment of archival materials (images, clippings, and more) are held in various collections at the following institutions:

Bibliothèque-Musée de la Comédie-Française.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Départment des Arts du Spectacle, Départment des Audiovisuels, Départment des Estampes et de la Photographie, Départment des Imprimés, Départment des Manuscrits).

Broadway Photographs. David S. Shields Collection [online]. University of South Carolina.

Harvard University, Houghton Library (Harvard Theatre Collection).

Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Service de Documentation).

Musée d’Orsay.

Museum of the City of New York.

Petite Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris (Service de Documentation).

Filmography

A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles:

1. Sarah Bernhardt as Actress

Hamlet, duel scene/The fencing match from the Schwob-Moran translation of Hamlet. Prod.: Paul Decauville, cam.: Clément Maurice Gratioulet, aut.: Marcel Schwob and Eugène Morand, based on play “La Tragique Histoire d'Hamlet,” ard.: Marguerite Vrignault (Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre France 1900) cas.: Sarah Bernhardt, Pierre Lagnier, Mlle Seylor, si, b&w (tinted), 35mm, 174 ft. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives, Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Cinémathèque Française, Deutsche Kinemathek.

Camille/La Dame aux Camélias/Dama du Camelii/Kameliendame/La Dama de las Camelias. Dir.: André Calmettes and Henri Pouctal, aut.: Alexandre Dumas fils. sc./adp: Henri Pouctal (Le Film d’Art, Pathé France 1911) cas: Sarah Bernhardt, Lou Tellegen, Paul Capellani, Henri Desfontaines, Pitou, Suzanne Seylor, si, b&w, 16 & 35mm, English intertitles, 1,099 ft. Archive: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Cinemateca Romana, Cinemateca de Cuba, Cineteca del Friuli, Filmoteca Española, Museum of Modern Art, BFI National Archive, Deutsches Filminstitut, Cinémathèque Française, Harvard Film Archive, Lobster Films, Library of Congress, Filmoteca UNAM, Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Gaumont Pathé Archives, Fundación Cinemateca Argentina.

Queen Elizabeth/Les Amours de la Reine Élisabeth/la Reine Élisabeth/Élisabeth, la Reine d’Angleterre/Queen Bess–Her Love Story. Dir.: Henri Desfontaines and Louis Mercanton, sc./adp.: Émile Moreau, based on Moreau's 1911 play “La Reine Elisabeth” (Histrionic Film Company UK/France 1912) cas.: Sarah Bernhardt, Lou Tellegen, Mlle. Romani, Albert Decoeur, Max Maxudian, Georges Chameroy, Marie- Louise Dorval, Jean Angelo, Guy Guidé, Guy Favières, si, b&w, 16 & 35mm, 3,300 ft. Archive: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Museum of Modern Art, Svenska Filminstitutet , Cineteca del Friuli, Library of Congress, BFI National Archive, Academy Film Archive, UCLA Film & Television Archive, George Eastman Museum.

Ceux de chez nous. Dir./prod.: Sacha Guitry (1915), cas.: Sarah Bernhardt, André Antoine, Edgar Degas, Anatole France, Lucien Guitry, Sacha Guitry, Octave Mirbeau, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Jean Renoir, Auguste Rodin, Edmond Rostand, Camille Saint–Saëns, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Cinémathèque Française, Lobster Films.

Jeanne Doré. Dir.: Louis Mercanton and René Hervil, adp.: Louis Mercanton, st.: Tristan Bernard (Éclipse France 1916) cas: Sarah Bernhardt, Raymond Bernard, Jeanne Costa, Suzanne Seylor, Jean-Marie de I’Isle, si, b&w, 35mm, 5,230 ft. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Cinémathèque Française, BFI National Archive.

Mothers of France/Mères Françaises. Dir.: Louis Mercanton and René Hervil, sc.: Jean Richepin (Éclipse France 1917) cas.: Sarah Bernhardt, Gabriel Signoret, Georges Denuebourg, Jean Angelo, Jean Signoret Jr., Berthe Jalabert, Louise Lagrange, si, b&w, 35mm, 5,144 ft. Archive: Lobster Films, Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Svenska Filminstitutet .

2. Sarah Bernhardt as Actress and/or Herself (fragments of unknown films/newsreels, a documentary home-movie, and more)

Sarah Bernhardt (Gaumont Pathé France n.d) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives [Note: Footage consists of four seconds of a panning outside shot; appears to be cast of Vingt ans après visiting with Sarah Bernhardt]

Sarah Bernhardt. (Pathé Frères Cinema UK 1913) si, b&w. Archive: BFI National Archive, UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Hendricks Can No. 15, 1905-15. (1916) si, b&w. Archive: Library of Congress [Note: Miscellaneous footage from Sarah Bernhardt's US visit].

Sarah Bernhardt at Home/Sarah Bernhardt Intime/Bernhardt à Belle Isle/Bilder aus dem Leben der welt berühmten Schauspielerin Sarah Bernhardt auf Insel Belle-Isle. Dir. Louis Mercanton (Hecla Film Company Ltd. 1915), cas: Sarah Bernhardt, Sir Basil Zaharof, Georges Clairin et al., si, b&w (tinted), 35mm, German intertitles, 1,361ft. Archive: Filmarchiv Austria, UCLA Film & Television Archive, Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée [Note: made in 1912 but released in 1915].

A la Nouvelle Orléans, Mme. Sarah Bernhardt assiste à une course hippique organisée en son honneur. (Gaumont Journal France 1917) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Meudon-Obseques de du sculpteur Auguste Rodin (Gaumont Journal France 1917). si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Sarah Bernhardt Addresses Crowd in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. (United States 1917) si, b&w. Archive: Library of Congress.

Sarah Bernhardt (Gaumont Pathé France 1918) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives [Note: Footage of Sarah Bernhardt arriving in New York during WWI].

France. Mariage d’Artistes Sacha Guitry epouse Yvonne Printemps (Gaumont Journal France 1919) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Greetings from Madame Sarah Bernhardt. (1920) cas: Sarah Bernhardt, Maud Tree, si, b&w. Archive: BFI National Archive.

Madame Sarah in “Daniel.” (Pathé Gazette UK 1920) cas: Sarah Bernhardt, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: BFI National Archive.

Sarah Bernhardt. si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives [Note: Three different scenes taken of Sarah Bernhardt between April 10, 1919 and March 1923].

Sarah Bernard [sic] s’embarque pour Belle-isle-en-Mer/Sarah Bernhardt à Belle-isle-en-Mer/A Belle Ile les touristes sont reçus par Madame Sarah Bernhardt (Gaumont France 1920) si, b&w Archive: Cinémathèque Française, Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Le Tournage de Vingt ans après (France 1922) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives [Note: Includes footage of cast visiting with Sarah Bernhardt].

The Divine Sarah. (Pathé Gazette France 28/03/1923) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Funeral of Sarah Bernhardt (Reuters Gaumont Graphic Newsreel, April 2, 1923) si, b&w. Archive: BFI National Archive.

Funeral of Sarah Bernhardt (British Pathé, April 2, 1923) si, b&w. Archive: BFI National Archive.

Les funérailles de Sarah Bernhardt (Journal Gaumont, 1923) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Les Obsèques de Mme. Sarah Bernhardt (Pathé Journal Actualité, March, 28, 1923) si, b&w. Archive: Gaumont Pathé Archives.

Sarah Bernhardt. (1923) si, b&w. Archive: EYE Filmmuseum.

B. Filmography: Non-Extant Film Titles:

1. Sarah Bernhardt as Actress

La Tosca, 1908; The Clairvoyant/La Voyante, 1923.

2. Sarah Bernhardt as Actress and Screenwriter

An Actress's Romance/Adrienne Lecouvreur, 1913.

3. Sarah Bernhardt as Screenwriter and Producer

It Happened in Paris, 1919.

C. DVD Sources:

Camille and Le duel d’ Hamlet. DVD. (David Menefee US)

Queen Elizabeth. DVD. (Grapevine Video US 2011)

Queen Elizabeth. DVD. (David Menefee US)

Mothers of France. DVD. (David Menefee US)

Paris 1900. DVD-R. (Grapevine US) - compilation documentary made in 1947 about Paris in the early 1900s, includes footage of stars like Bernhardt.

D. Streamed Media:

Sarah Bernhard 1915. (Excerpt of Sarah Bernhardt with Sacha Guitry and an unknown women, maybe on the set of Ceux de chez nous).

Madame Sarah Bernhardt in “Daniel.” (Three excerpts that appear to be sequential although the third does not mention it is the death scene in “Daniel”): Excerpt 1, Excerpt 2, Excerpt 3.

Funeral of Sarah Bernhardt. (Reuters Gaumont Graphic Newsreel). April 2, 1923.

Excerpt of Sarah Bernhardt in “La Tosca” (British Pathé 1905) (It is unclear if this is related to 1908 film with same name).

The Gaumont Pathé Archives contains a great deal of streamed media relating to Sarah Bernhardt. A login is required to view these materials:

Credit Report

Sarah Bernhardt’s filmography was compiled using information from film trade journals, as well as the AFI catalogue and the FIAF database. While much information exists about Bernhardt’s involvement in the theater, it is unclear the degree to which her role as actress shaped and impacted the making of her films. Copies of prints also vary. The film of Camille that was screened at Il Cinema Ritrovato, in Bologna, in 2006 (from the Cinémathèque Française) does not include the opening scenes in Camille available in the copy held in the National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. We therefore still need to determine the placement and sequence of scenes in some of her key films. The length of Camille and Queen Elizabeth varies considerably. For Camille, I have listed the length of the print held in the Cinémathèque Française and for Queen Elizabeth the length of the copy held in MoMA. However, when I contacted the NFSA, Canberra, to verify the length of their holdings (since their copy of Camille contains the opening scenes), Clare Norton told me that: “Unfortunately our catalogue record doesn't state the length of either film in feet or meters. However, working backwards using a 'feet to time' converter that our Collection Reference has here within their team database, a running time of 35 minutes [Queen Elizabeth] is approximately 1265 ft. and a running time of 25 minutes [Camille] is approximately 900 ft. These figures are based on 16mm film run at 24 frames per second.” These lengths are clearly different from those I have listed. Further, the available DVD of Camille does not have the NFSA’s opening scenes; it also has titles written by the producer of the DVD and these have been inserted into the film in places that depart from the placement of titles in extant archival copies. Finally, David Menefee states that a copy of La Voyante exists, but I have not been able to confirm this (Menefee 2012, 346).

Citation

Duckett, Victoria. "Sarah Bernhardt." In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2015. <https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-cqt4-pc13>