Mrs. Maria C. Downs (née Godoy), variously referred to as owner, proprietor, and manager, opened the Lincoln Theatre in Harlem in 1909. The theater, a nickelodeon and vaudeville theater that openly catered to the neighborhood’s Black community, was the first of its kind in the city, which operated under de facto segregation. Downs sought Black patronage, booked Black performers, and did not segregate her customers. While it is unclear if she was born in the United States, Downs lived in New York City and self-identified as Cuban (Jackson 94). Secondary sources, however, are conflicted on her race: Bernard L. Peterson’s The African American Theatre Directory notes that she was “white or nonblack” (125), while Eric Ledell Smith’s African American Theater Buildings describes her as “African American” (146). Primary sources, including the trade press and Black newspapers, either left off a descriptor or labeled her as white. Regardless of her identity, Downs quickly gained a reputation as a “charming, genial, and most courteous” proprietor (“Owner of New Lincoln Theatre on European Trip”), whose theater became “a part of the life of the colored people of Harlem” (“At the Nation’s Metropolis”).

Before getting married and investing in the Lincoln, Downs was a prima donna with a flair for the dramatic. She performed in the city as early as 1893, appearing at the Eden Musée as a “Spanish troubadour” (“Changes at the Theatres”). “I loved the theatricals,” she noted in a 1924 interview with Billboard, “and that love persisted even after my husband and his business obliged me to forsake the stage after our marriage” (Jackson 94). This interest led her to invest sight unseen in the uptown storefront theater at 135th Street and Seventh Avenue that she turned into the Lincoln. Then known as the Nickelette or Nickolette, the theater had a capacity of just 167 seats. After managing the place by herself for six months, she employed further help and expanded it to 300 seats. For around $300/week, she put on a mixed bill with four live performances and a film screening. About five years later, in 1915, Downs expanded the Lincoln yet again to 1,000 seats. By the 1920s, Downs was paying about $2,500/week for film rentals and performer salaries, offering a fifty-minute performance coupled with a feature film or serial installment and a newsreel, all with a top ticket price of 50 cents.

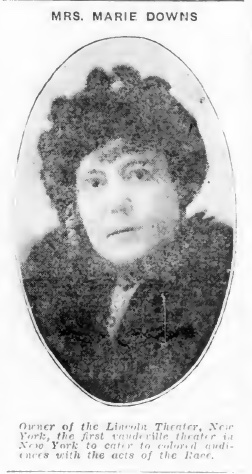

Maria C. Downs, date unknown, before opening the Lincoln Theatre. Billboard (December 13, 1924): 94.

Though Downs almost always put on a mixed bill at the Lincoln, the theater is most well-remembered for its promotion of Black performance. For example, various stock companies were formed at the theater, including the Anita Bush Stock Company, and the theater offered early performances by some of the best-known Black entertainers of the day, including Florence Mills, Clarence Muse, Ma Rainey, and Ethel Waters. As Mary Carbine and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart have explained, mixed bills were not uncommon in early twentieth century Black urban theaters as live performances supposedly provided “more authentically ‘Black’ forms of entertainment” (Stewart 163; Carbine 21) and received more frequent and favorable attention in the press before films gained in popularity (Stewart 127-129). Still, Downs actively linked her promotion of Harlem stage talent to the film industry, asserting that “some of these artists have acquired fame in the motion picture field” (Jackson 94). She also embraced film production activities, such as when the Lincoln was used as a location for screen tests for a major motion picture, most likely King Vidor’s Hallelujah (1929). “The Lincoln,” one article shared, “will inaugurate a series of screen tests to find out if any patron of the theatre will be among the lucky ones to be selected for the million dollar motion picture to be made by one of the leading firms in the United States” (“Lincoln Theatre to Give Screen Tests”).

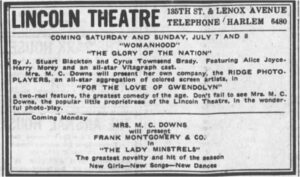

The Lincoln’s film offerings were certainly not ignored by reviewers and critics. The theater’s bills regularly offered mainstream American features like Where Are My Children (1916), Male and Female (1919), The Ten Commandments (1923), The Great Gatsby (1926), and serials, including The Grip of Evil (1916) and The Bar C Mystery (1926). Downs also showed race films, such as The Colored American Winning His Suit (1916), Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920), and Doing their Bit (1918), a film featuring actuality and local shots of Black soldiers produced by the New York City-based Toussaint Motion Picture Exchange. In one case, it appears that Downs may have had a role in one of the race films shown at the theater. A 1917 advertisement read: “Mrs. M.C. Downs will present her own company in the Ridge Photo Players, ‘For the Love of Gwendolyn,’ in an all-star cast of colored artists” (“To Present Negro Picture”). Confusingly written, the advertisement could be read as an announcement of her role in the film or her ownership/management of the Ridge Photo Players. Perhaps offering a bit of clarity, another advertisement warned: “Don’t fail to see Mrs. M.C. Downs, the popular little proprietress of the Lincoln Theatre, in the wonderful photo-play” (“Lincoln Theatre to Have Lady Minstrels”). Beyond these two articles, it is difficult to locate more on Downs’s potential film appearance or any potential relationship to the Ridge Photo Players.

Advertisement for Mrs. M. C. Downs’s appearance in For the Love of Gwendolyn. New York Age (July 5, 1917): 6.

Downs’s commitment to her audience and to quality shows only grew with advancements in film technology. In 1928, it was reported that Downs made the decision for the Lincoln to become one of the first Black-oriented theaters to be wired for sound. She also changed her film policy: for the first time, she would shift to offering only Black films (“Harlem Wires Theatre”).

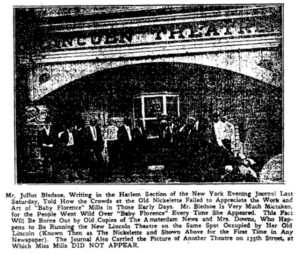

Despite opening the Lincoln in 1909 and its status as the first theater in Harlem to cater to the growing Black population there, neither Downs nor the Lincoln are mentioned by the city’s leading Black weekly, the New York Age, until 1916. By then, the paper was forced to note that “the Harlem theatre goer is quickly becoming adicted [sic] to the movie [sic], as is evident by the manner in which the big photoplays are received by the large audiences that nightly frequent the Lincoln (“The New Lincoln Theatre” [June 22, 1916]). This absence in the press may have been a deliberate refusal to acknowledge Downs’s theater given its initial status as a storefront nickelodeon. Nickelodeons like the Lincoln were deemed immoral and dangerous by reformers, and “contributed to the tenuous position of moviegoing as a legitimate leisure activity” (Stewart 161). A line in a New York Amsterdam News article nearly twenty years after its opening confirms this: “many will recall that it was not considered ‘the thing’ among the so-called social elite to patronize the Nickollete” (“Mrs. Downs’ Lincoln”). It may be the case that the final stage of Downs’s renovation to the theater in 1915 removed any vestiges of its nickelodeon past, making it possible for more reform-minded, middle-class journalists to report on Downs and her theater.

Though we know almost nothing about Downs’s husband Henry, he “took no part in the running of the house, leaving this to his charming little wife” (“Mrs. Downs’ New Lincoln”). Yet Downs likely still benefited from the respectability added to her name through the formal title of “Mrs,” which was always used when she was referenced in the press (Caddoo 33-34). Even after Henry passed away around 1924, Downs, donned in mourning attire, maintained her married name and her stake in the theater, refusing any offers to sell—this despite a few extensive overseas trips to Europe during that period (“Owner of New Lincoln Theatre on European Trip”; “New Lincoln Owner”). The press, both trade and local, certainly afforded Downs a distinct respectability and praise by the time journalists started reporting on her. In her role at the Lincoln (which was alternatively listed as owner, proprietor, or manager in various newspapers, though it is certain that she had some, if not a significant, say in its operation) she was consistently praised for her charity work and promotion of Black talent. In other words, like some other women exhibitors, her work at the theater was usually tied to the betterment of the community, not merely a business venture.

Indeed, Downs considered her theater ownership less a money-making scheme and more a means to give something back to Harlem’s Black community. Beyond her emphasis on Black performers and entertainers, she regularly donated money and the theater space for charity functions. For example, she annually provided free Thanksgiving and Christmas shows for Harlem’s poor children in conjunction with a local chapter of the Knights Templar, and donated to the Salvation Army’s attempts to build a home for destitute and needy men in Harlem. While the managers at the Lincoln were always white men, Downs did employ Black men and women from the local community. It seemed she also fostered an environment that made for employee longevity. By the mid-twenties, the pianist had been there since the theater opened and the band, ticket taker, and cashier were there for around seven years. Over the course of her long tenure at the “pioneer playhouse” (“Lincoln and Alhambra Theatres”), Downs only had one very large, publicly shared spat with her employees when she accused her manager, cashier, and ticket taker of stealing money from the theater.

Similar to Josephine Stiles, a Black businesswoman who opened the first Black theater in Savannah, Georgia, the same year that Downs opened the Lincoln, Downs’s monetary investments were not limited to just the motion picture business (Newsom 31-32). She held property throughout the city and was president of the H. Hicks & Sons Corporation, a grocery store, and Hicks-Downs Realty Corporation. Yet despite all of these investments, one journalist in the Age insisted that “her interest in this playhouse has always been closest to her heart” (“Two Harlem Theatres”)

In the aforementioned 1924 interview in Billboard, Downs’s closing words provided a reflection on her by then twenty-five-year career: “Isn’t it wonderful to be a part and parcel of a big human movement that means progress for a whole people? There is a profit in it that’s not measured in terms of money” (Jackson 95). And yet, despite Downs’s affinity for her work at the Lincoln, she sold her interest in the theater in early 1929 to Frank Schiffman, who took over the theater and owned most of Harlem’s theaters by that year (“Schiffman Leads Amusement World”). Schiffman maintained the theater for less than a year before selling it again (“Lincoln Theatre Reopens”). The Lincoln lasted about six months under this new ownership before it was sold to the Mt. Moriah Baptist Church (Romilio). It is difficult to ascertain what exactly Downs did after she “retire[d] from the theatrical business” (“Mrs. Downs’ New Lincoln”). Lamenting the loss, Romeo Dougherty, a critic and friend to Downs, wrote in the New York Amsterdam News, “this paper is forced to witness the passing of Mrs. Downs and her assistant with a great deal of regret, for the harmonious contact of twenty years cannot be suddenly withdrawn without leaving a void which only Time can fill” (Dougherty).

In many ways the history of the Lincoln Theatre is nearly synonymous with Downs’s career. At the moment that she sells the Lincoln, Downs also drops out of the public record. Downs’s positionality as a wealthy woman with a respectable reputation and connections to the theatrical world certainly gave her the means to have such sway and ability in Harlem. Indeed, her interest in theater and film seems to have emerged from these experiences and made it possible for her to act as an important influence in Harlem’s entertainment scene, both in terms of live performances and film, for two decades. Yet, so much more is unclear about Downs and her career before and after the Lincoln. And beyond a recommendation from a friend, why did she become invested in Harlem’s theatrical and film scene? What was her involvement in For the Love of Gwendolyn? Did she appear as herself or a character? Was she a backer for the film company or did the performing company appear at the Lincoln? Did her interest and financial support for Black performers and film end with her sale of the Lincoln? Did her trips to Europe or home to Cuba (Jackson 95) involve a similar patronage of these art forms? And, perhaps most basically: what years bracket her life? Where was she born? Where is her final resting place? Census records are inconsistent here: one possible reference gives a birthdate of 1889. But this conflicts with a marriage certificate between a Maria C. Godoy to a Henry Downs dated 1901. Elsewhere, a plain, unadorned gravestone in a Masonic cemetery in upstate New York reads: “Maria C. Downs 1871-1954.” These lingering questions reveal the fact that what remains known of Downs, though relatively detailed compared to the lives and businesses of some American women involved in early Black silent film, is only a small sliver. Future research could delve deeper into her New York City connections, explore potential linkages between performers at the Lincoln and film work, or, perhaps, investigate her voyages abroad to determine any relationship between her career in Harlem and international Black performance and film networks.