Little is known—and even less is written—about the role that women played within the Spanish silent cinema. Cinema, along with other visual arts, constituted what was known then as a frivolous entertainment industry. Although, in many countries it was an area that was more open to the presence of women than other established businesses or artistic fields, in Spain we can find very few names of women pioneers who gained the space to experiment and the freedom to create. However, Helena Cortesina was one of them. Cortesina started her career as a dancer in variety shows, then moved to acting, and then became a director and producer with the film Flor de España o la Leyenda de un Torero/Spanish Flower or the Bullfighter’s Legend (1921).

From left to right: Helena Cortesina with her sisters, Ofelia and Angélica, year unknown. Courtesy of the Archivo General de la Administración.

Cortesina managed to enter the Madrid cultural elite before the Civil War in 1936. Despite being one of the few women directors in the early Spanish cinema, she has not been studied by academia, and there are few references to her in encyclopedias and other overview books, which are full of undocumented and misleading information. Incongruities go as far as asserting that Flor de España had only been directed by its screenwriter José María Granada, even though all the press releases from the 1920s attribute the sole responsibility of the film to Cortesina.

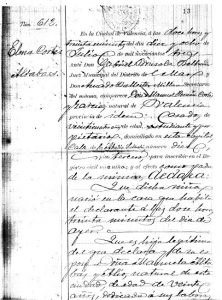

Her absence in the official history of the Spanish cinema, and the disappearance of the film and other personal documents, such as diaries or letters, determined the methodology of this research project to be one of archival science. Consulting press documents, libraries, museums, and archives, I found her birth certificate, being able to establish the authenticity of her name and date of birth for the first time. Cortesina was the oldest daughter in an artistic family. She began her career as a variety show dancer as a teenager, touring across Europe. Following in her footsteps, her sisters, Ofelia and Angelica Cortesina, were also performers and eventually formed part of the cast of the film she directed. They were known in the press as the “Hermanas Cortesina,” thus making it difficult to distinguish between the three in reviews and articles. However, Helena, a dancer influenced by classical Greek art, stood out from the others by choosing music from respected Spanish composers, such as Isaac Albéniz, Manuel de Falla, and Enrique Granados.

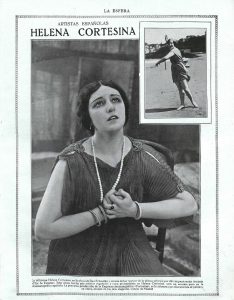

Her popularity started to grow thanks to her high visibility in the press, where she was often called “Venus valenciana” and praised for her sculptured body and talent as a ballerina. Helena even modeled for the famous Impressionist artist Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida for the painting “Danzarinas griegas”/ “Greek dancers” in 1917. A first sketch of the painting, found on the website of the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, led to discovery of the friendship between Sorolla and the Cortesina family. This fact can be verified by the correspondence from Helena’s mother to the painter that is kept in the Sorolla Museum in Madrid.

Cortesina made her cinema debut in 1920 with the film La Inaccessible/The Unapproachable Woman. The film was well-received, especially for Cortesina’s performance. For example, a writer going by the initials M.R. in La Correspondencia de España advocated that Cortesina was “not to stray far from cinematography, not to mistake it as a secondary art, but as the main career move for her future, a future full of glory, popularity and fabulous contracts” (1921, 3).

Cortesina’s transition from the theatrical stage to the silent film industry was a common career move in Spain for both men and women due to the lack of professional actors in the new medium. The theater world in Madrid was very conservative and close-minded, which made it difficult for new talents to break through (Dougherty and Vilches 1990, 37). Because of this, Cortesina established her acting career in the film industry very rapidly; her presence was welcomed and not overlooked despite her past as a variety show dancer.

Helena Cortesina with Florián Rey in La Inaccesible (1920). Courtesy of the Archivo General de la Administración.

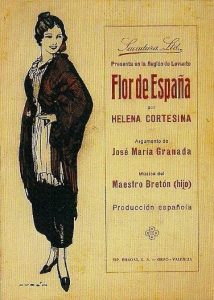

Enjoying her economic independence, and motivated by the success of La Inaccesible, Cortesina decided to invest in her own film production company, Cortesina Films. In 1921, she produced and directed her first and only film, Flor de España. Mundo Gráfico announced the creation of Helena’s company on May 25, 1921:

Ladies and gentleman: we have a new Madrilenian film production company. The beautiful dancer Helena Cortesina, praised by her successful role in La inaccesible, is jumping into the arms of the cinematographic industry. Like the North American film stars, she will produce her own films and choose her own cast. We sincerely hope to see beautiful Helena, if she has success, as she is bound to, to take this enterprise to a successful conclusion (Prada 31).

With this new film project, in which she would star, Cortesina could establish her professional credentials and support her sisters’ burgeoning careers in the new medium. The Cortesina family was used to collaborating with one another and helping to launch each other’s careers. For example, another joint venture, which most likely never left the planning stages, was the “Great Cortesina Company,” a project that was to allow them to tour around Europe performing Spanish songs and dances.

Flor de España was a melodrama about a bullfighter named Juncales (Jesús Tordesillas), following him from the beginning of his career up through fame and success. Having achieved his dreams, he becomes tired of his success and marries the dancing star “Flor de España” (Cortesina), who, years before, as an insignificant flower girl, had been his girlfriend. Both the storyline and the mise-en-scène were directly influenced by common topics in Spanish culture, which was a tactic consciously adopted by Cortesina and the scriptwriter Granada, who believed stereotypical representations constituted the best strategy to sell Spanish culture abroad (Fernández Fígares 2002, 260; Brasa 1927, 15). The film was officially released on February 13, 1923, in Madrid.

Helena Cortesina in Flor de España (1921), featured in La Esfera in 1921. Courtesy of the Hemeroteca Digital, Biblioteca Nacional de España.

After this cinematographic experience, Cortesina was able to transition back to a professional career in theater, which was her real goal because it had greater artistic and cultural prestige. Her first collaboration with a renowned theater group was with the Catalina Bárcena and Gregorio Martínez Sierra Company. It was within this company, in 1921, that Cortesina met her partner, the stage designer Manuel Fontanals, with whom she would have a relationship for the next fifteen years and two children. Through her involvement in the company and her relationship with Fontanals, Cortesina gained access to the intellectual elites of Madrid, making friends with some of the most renowned artistic figures of the time, the famous Generation of ‘27: Federico García Lorca, Rafael Alberti, and María Teresa León, among others. During these years, Cortesina’s career in the theatrical world pushed her further and further away from the film industry. She joined the Lola Membrives Company, with whom she would perform in numerous plays from famous Spanish and Argentinian playwrights.

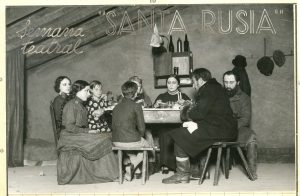

Helena Cortesina (seated on right), in scene from “Santa Rusia” (1932), in Teatro Beatriz in Madrid with the Lola Membrives Company. Courtesy of the Archivo General de la Administración.

Her second pregnancy (not recognized by Fontanals), and the death of her daughter, led to her separation from her partner. However, Cortesina did not give up on her cultural and political interests and, in September 1936, with the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, she joined the Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals for the Defense of Culture. Cortesina and her son Juan Manuel Fontanals were forced to go into exile. According to the database Centro de Estudios Migratorios Latinoamericanos/Center for Latin American Migratory Studies, Cortesina’s family arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on June 3, 1937, on the boat Lipari, in order to escape Spanish fascism. She joined the Argentinian artistic scene, taking parts in films along with other Spaniards in exile. She did not abandon her theatrical career, and with Andrés Mejuto, she created her own company. Together they produced a large number of Spanish plays and enjoyed great success in Argentina. Cortesina died at the age of eighty on March 7, 1984, in Buenos Aires.

Future research on Cortesina’s film career should focus on studying the practical conditions of the production and shooting of Flor de España. We need a more in-depth understanding of Cortesina’s behind-the-scenes work on the film. We still have much to learn about the history of Spanish cinema and the involvement of women during the silent film era.