by

Laura Vichi

Although Eliane Tayar is undoubtedly a fascinating figure, she is a relative footnote in any study of the silent film era, having made her first appearance as a film actress at the end of the 1920s. Daughter of Salomon Tayar, a Libyan stockbroker of Caucasic origins, and of Jeanne Monteauzé, a French woman, she had a difficult childhood. She lost her mother when she was six years old and grew up in a convent until the age of seventeen, marrying soon after in 1921. It may be that she established contacts in the cinema world through her first husband, Fraisse Zamisky, who was probably introduced to her by her father, and who was a banker and owner of the celluloid factory Anel et Fraisse. Tayar’s father died in 1922 and Zamisky, who was addicted to gambling, killed himself in 1923 after filing for bankruptcy (Mazet 2000, 14). At nineteen years old, Tayar was both orphan and widow. She had a younger sister, Henriette, who studied fine arts starting in 1930 and most likely introduced Eliane into the Parisian artistic milieu.

Practically speaking, Tayar was a self-taught woman. Keen on reading and history, she was acquainted with several important intellectuals of her time, including Louis-Ferdinand Céline whom she met in 1930, together with film critic Aimée Barancy, on the houseboat “Le Malamoa,” which was the painter Henri Mahé’s studio. The relationship between Tayar and Barancy is detailed in Eric Mazet’s introduction to his 2000 edited collection of Céline’s letters (7-32). In late 1930, Tayar began writing for the journal Le Courrier cinématographique and for the film magazine Pour vous in 1931.

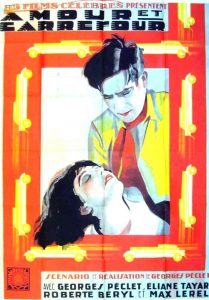

Poster for Amour et carrefour (1929).

Tayar’s exotic beauty, her big green eyes and olive complexion, did not pass unnoticed, and, beginning in 1928, she was invited to appear in a few films. According to her daughter, Colette Forestier, she would have preferred to become a poster designer, which was a male-dominated profession at that time (2006, n.p.). In 1928 and 1929, she worked on several film sets as an extra or in supporting roles. From the magazines of her time, it is clear that Tayar was considered an emerging film star (e.g., Despa 1928, 21-22). Yet, the only film in which she played the lead role is Georges Péclet’s Amour et carrefour (1929), a comedy where her character seems to exhibit qualities similar to Tayar’s, for she is outgoing, active, enterprising, and a sports car lover, especially of the Bugatti (Barancy 1929, 54).

However, she did not become a star actress. Instead, Tayar’s exuberant and ambitious nature, which is evident in her writing style and her willingness to take minor parts, led her to become an assistant director. Tayar felt the need to give herself to this profession completely and wanted to become more involved in various aspects of filmmaking. On December 6, 1930, in Le Courrier cinématographique, she expresses her position: “Assistante…c’est bien moins glorieux que d’être artiste, mais c’est faire partie de l’équipe; c’est être liée intimement avec tout ce qui est le cinéma proprement dit” [Trans.: Assistant… it’s less prestigious than an artist, but it means to belong to the team; it means to be intimately connected to everything that cinema is] (11). She started her career by working with Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer, whom she may have met through the cameraman Gösta Kottula, one of Mahé’s “Malamoa” regulars. In 1928, she worked as an extra and, according to her daughter Colette, became the assistant director on the silent classic La Passion de Jeanne D’Arc (1928) after the shooting of the film had already started (Forestier n.p.).

Barancy’s 1933 “L’archange et les vampyres,” her first published piece, describes her friend Tayar’s attempt to become the lead actress in Vampyr (1932) (307-338), but this may be a fictional account. What is certain is that Tayar worked as Dreyer’s assistant between the summer of 1930 and the beginning of 1931. The film was Vampyr and the director entrusted her with finding locations and set pieces for it. However, this experience turned out to be traumatic because of the director’s difficult, if not impossible, demands. Tayar wrote about this experience in a series of articles in Le Courrier cinématographique titled “Quand j’étais assistante de Carl Dreyer,” which ran from December 1930 to February 1931. However, her relationship with Dreyer continued. When the director was asked by the leaders of the Fédération Nationale des Blessés du Poumon et Chirurgicaux/The National Federation of Lung and Surgical Wounds (FNBPC) to make a documentary film about the sanatorium under construction in Clairvivre in Salagnac, Dreyer sent Tayar.

Eliane Tayar, in 1928 in Le Courrier cinématographique. Private Collection.

Before shooting La Cité sanitaire de Clairvivre (1935) between the summer and the fall of 1933, Tayar co-directed Versailles (1934) with Maurice Cloche. This documentary film was received positively by the critics because, even if its subject matter was considered quite challenging, the film managed to break from established models of both tourist films and cinematic portrayals of historic events (Fainsilber 1933, 826; Mazet 21). Later, Tayar entrusted a print of Versailles to Henri Langlois, but the film is presently missing from the archives of the Cinémathèque Française.

A 35mm print of La Cité sanitaire de Clairvivre was discovered in 1999 in the basement of the village film theater by Gabriel Peynichou, the grandson of the man who founded the Clairvivre theatre. Clairvivre had a very challenging goal, since not only was it supposed to make the public aware of the FNBPC, but its mission was also to spread Clairvivre’s ideals. In a style reminiscent of Eisenstein’s The General Line (1929), the film shows tuberculosis as a disease determined by social and economic factors and proposes the utopian solution embodied by Clairvivre, “lieu de paix et de fraternité” [a place of peace and fraternity], where life is based on citizen cooperation. Modern, well-equipped facilities and lodgings were set up in the village thanks to agricultural, commercial, and industrial activities. The film promotes an idea of modern life close to that trumpeted by architect Le Corbusier who believed that architectural structures must optimize their residents’ health and welfare. The camera pays attention to both the structures and the machinery in this new town and the faces of the citizens, highlighting both the modernity of the buildings and the town’s humanity. We see patients who no longer need to leave their families to be cured, as an intertitle says at the beginning: “Living like all the other people.” This approach to illness was not obvious, since it conveyed the will of creating a community and a model for a new society where everybody would give his or her contribution in proportion with his or her possibilities (Moreau 2002, 148-149). In Clairvivre, Tayar met her future husband, architect and town planner Pierre Forestier, creator of the modern sanatorium town (Moreau 41).

From the extant documentation, it is possible to speculate that Tayar held ideals that we would understand today as feminist. Moreover, she was an appreciated figure in the cinema industry, as we can read in a letter from Céline about the project of translating the story Secrets dans l’île, previously called Ouessant and then Tempête (Mazet 35), into a film: “Les personnes consultées te trouvent un talent ‘fou.’ J’ai ajouté ‘génie’ et je m’y connais” [Trans.: The people who have been consulted find that you have a ‘tremendous’ talent. I added that you were a ‘genius,’ and I know a thing or two about that] (Mazet 41-42). He concludes by saying that he is sure that Jacques Deval, the director of the future film (which, in the end, was not made), would give Tayar “la place,” or the assistant director position. Tayar wanted to make the film after seeing Jean Epstein’s Finis terrae (1929), which enthused her (Mazet 35). Nevertheless, as her daughter Colette recollected, it seems that since she was not encouraged by her husband and her family in general, Tayar reduced her film activity to dedicate herself to the Montessorian education of her daughter, who was born in 1936 (Forestier n.p.). After La Cité sanitaire de Clairvivre, Tayar worked on a few other documentary films—an unidentified title on Chartres (1937-38) and Orléans (1938). Later, she worked as Jean Vidal’s assistant on Le Roi Soleil (1958) and then on a series of three films on the French Revolution. Orléans is still extant, but it does not have the same freshness as Clairvivre. Tayar’s role on the 1938 film was limited to a technical one as it was directed and produced by Jean-Claude Bernard. However, it is possible to notice the same attention of the camera to architectural structures as seen in Clairvivre. One can safely say that Tayar’s greatest film remains Clairvivre, her most ambitious project.

Tayar’s career and her commitment to documentary cinema deserve more investigation. The story of each of her films needs more research too, since we know little or nothing about them. Finally, a Tayar collection (presently there are only some scattered archival sources), even if small, would be worth setting up in a public establishment, not only for its intrinsic value, but also because Tayar’s career represents a cross-section of key moments in French film and cultural history from the 1920s to the 1960s. Moreover, she represents a case study in women’s history: her whole life and career represent a further piece in the male-dominated panorama of the cinematic industry and, ultimately, of society.

Bibliography

Barancy, Aimée. “L’archange et les vampyres.” Les œuvres libres 139 (January 1933): 307-338.

------. “Un quart d’heure avec Eliane Tayar.” Cinémagazine 28 (12 July 1929): 54.

Bierre, René. “Quand on tournait le film de ‘Clairvivre,' ville d’harmonie et de lumière.” Pour vous 331 (21 March 1935): 11.

Chirat, Raymond, ed. Catalogue des films français de long métrage. Films de fiction 1919-1929. Toulouse: Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 1984.

Chirat, Raymond, and Jean-Claude Romer, eds. Catalogue des films de fiction de première partie 1929-1939. Service des Archives des Films du CNC, 1984.

Despa, M. “Eliane Tayar.” Le Courrier cinématographique 20 (19 May 1928): 21-22.

Fainsilber, Benjamin. “Entretien avec Maurice Cloche.” Cinémonde 259 (5 October 1933): 826.

Forestier, Colette. Personal Interview. 23 December, 2006.

Francès, Robert. “Embrassez-moi.” Le Courrier cinématographique (6 October 1928): 33-34.

“Les principaux films documentaires et reportages filmés en 1935, 1936 et début 1937.” La Cinématographie française 973 (25 June 1937): 257.

Mazet, Eric, ed. Au fil de l’eau: lettres de Louis-Ferdinand Céline à deux amies, Aimée Barancy et Éliane Tayar, et documents annexes. Tusson: Editions du Lérot, 2000.

Moreau, Pierre. Clairvivre, une ville à la campagne. Paris: Editions du Linteau, 2002.

S.A. “Artiste et assistante!” Le Courrier cinématographique 48 (29 November 1930): 17.

------. “Champagne. ” Pour vous 450 (1 July 1937): 11.

Tayar, Eliane. “Quand j’étais assistante de Carl Dreyer.” Le Courrier cinématographique 49 (6 December 1930): 11; 50 (13 December 1930): 16; 51 (20 December 1930): 16-17; 52 (3 January 1931): 33-34; 53 (10 January 1931): 15; 54 (17 January 1931): 22; 56 (31 January 1931): 21; 57 (7 February 1931): 23-24; 8 (21 February 1931): 17-18. Partially reprinted in Dreyer, Carl Th. Réflexions sur mon métier. Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 1997. 169-181.

------. “Quelques clairs secrets du ‘Vampire.'” Pour vous 205 (20 October 1932): 11.

“Une présentation de films documentaires organisée par les Grands Réseaux Française.” La Cinématographie française 971 (11 June 1937): 14.

Vidal, Jean. “Clairvivre.” Pour vous 340 (23 May 1935): 12.

Wahl, Lucien. “Versailles.” Pour vous 257 (19 October 1933): 14.

-----. “Vivre.” L'Œuvre (22 March 1935): n.p.

Archival Paper Collections:

Various journals. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Fonds Albatros, Fonds Henri Fescourt, Fonds Yves Kovaks, Fonds Robert Lachenay. Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française.

Filmography

A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles:

1. Eliane Tayar as Director and Screenwriter

La Cité sanitaire de Clairvivre. Dir./sc.: Eliane Tayar, cam.: R. Moreau and G. Clerc, mus.: Michel Levine (Fédération Nationale des Blessés du Poumon et Chirurgicaux [FNBPC] FR 1935) sd, b&w, 35mm. 1932 ft. (21 min). Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée.

2. Eliane Tayar as Director

Orléans. Dir.: Eliane Tayar (Les Films J.C. Bernard FR 1938), commentary: Roger Leenhardt, cam.: G. Raulet and M. Théry, sd, b&w, 35mm, 16mm, 1722 ft. (19 min). 1 reel. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Cinémathèque de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (16 mm), Cinémathèque Française (1280 ft., 35mm English print).

3. Eliane Tayar as Assistant Director

La Passion de Jeanne D’Arc. Dir./sc.: Carl Theodor Dreyer, ed.: Carl Theodor Dreyer, Marguerite Beaugé, ph.: Rudolph Maté (Société Générale des Films FR 1928) cas.: Renée Falconetti, Eugène Silvain, Maurice Shutz, Louis Ravet, André Berley, Antonin Artaud, Gilbert d'Alleu, Jean d'Yd, Paul Delauzac, si, b&w, 35mm, 16mm, 1/2" video. 7251 ft. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Bulgarska Nacionalna Filmoteka, Cinémathèque Française, Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, Cinemateca Brasileira, Cinemateca do Museu de Arte Moderna, Svenska Filminstitutet , Deutsches Filminstitut, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Filmoteca Española, Filmoteka Narodowa, George Eastman Museum, Museum of Modern Art, Národní Filmov Archiv, BFI National Archive, Österreichisches Filmmuseum, Gosfilmofond, Cineteca Nazionale, Fondazione Cineteca Italiana, Cinemateca Romana, Cinémathèque Québécoise, Norwegian Film Institute, UCLA Film & Television Archive, UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, Deutsche Kinemathek, Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, Harvard Film Archive, Danske Filminstitut, Jugoslovenska Kinoteka, Anthology Film Archives, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Academy Film Archive, Lobster Films, Cineteca Nacional, EYE Filmmuseum, Cinemateca Nacional de Angola.

Vampyr ou l'étrange aventure de David Gray. Dir.: Carl Theodor Dreyer, sc.: Christen Jul, ed.: Tonka Taldi, ph.: Rudolph Maté, mus.: Wolfgang Zeller (Tobis Klangfilm FR/DE 1932) cas.: Julian West, Maurice Shutz, Sybille Schmitz, Rena Mandel, Albert Bras, Henriette Gérard, Jan Hieronimko, Jane Mora, sd, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Danske Filminstitut, Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna.

4. Eliane Tayar as Actress

La veine. Dir.: René Barberis, adp.: Albert Jean, cam.: André Reybas, (Société des Cinéromans FR 1928) cas.: Sandra Milovanoff, Paulette Berger, Elmire Vaultier, Eliane Tayar, Norman Rolla. André Nicolle, Jules Moy, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Lobster Films.

5. Eliane Tayar as an Extra

Should a Girl Marry?/Destin de femme. Dir.: Scott Pembroke (textes version française: Lucie Derain) (Trem Carr Productions FR 1928) cas.: Helen Foster, Donald Keith, si., b&w, 35mm. 3281 ft. (83min). 7 reels. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée.

L’âme de Pierre. Dir./adp.: Gaston Roudès, cam.: Albert Duverger (Gaston Roudès FR 1928) cas.: Jacqueline Forzane, France Dhélia, Sylviane De Castillo, Eliane Tayar, Georges Lannes, Gilbert Dany, Léon Malavier, Maurice Schutz, Jean Godard, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Cinémathèque Française.

L’argent. Dir./adp.: Marcel L’Herbier, ph.: Jules Kruger (Société des Cinéromans FR 1929) cas.: Pierre Alcover, Marie Glory, Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel, Yvette Guilbert, Henry Victor, Pierre Jouvenet, Marcelle Pradot, Antonin Artaud, Jules Berry, Alexandre Mihalesco, Jean Godard, Raymond Roulot, Armand Bour, si, b&w, 35mm. 12,139 ft. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée. [Note: Tayar is one of the three telephone operators].

L’eau coule sous les ponts. Dir.: Albert Guyot (FR 1929) cas.: Mireille Severin, Jacques Arnna, Blanche Beaume, Eliane Tayar, Johann van Canstein, si, b&w. 35mm. Archive: Cinémathèque Française.

Monte-Cristo. Dir./adp.: Henri Fescourt, ed.: Jean-Louis Bouquet, ph.: Julien Ringel, Henri Barreyre, Goesta Kottula, Maurice Hennebains (Les Films Louis Nalpas FR 1929) cas.: Jean Angelo, Lili Dagover, Gaston Modot, Marie Glory, Jean Toulot, Michèle Verly, Pierre Batcheff, Rozet, Germaine Kerjean, Henri Debain, Ernest Maupain, Bernard Goetzke, si, b&w, 35mm, 18,832 ft. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée.

B. Filmography: Non-Extant Film Titles:

1. Eliane Tayar as Director

Versailles, 1934; Champagne, 1937; La Cathédrale de Chartres (ca. 1937-1938).

2. Eliane Tayar as Actress

Embrassez-moi!, 1928; Amour et carrefour, 1929.

C. DVS Sources:

Clairvivre. Enquête sur une utopie. DVD/VHS. (France 3/Lilith Production/Chamaerops Productions France 2001) - contains parts of La Cité sanitaire de Clairvivre (1935).

Histoire de Clairvivre. VHS. (Chamaerops Productions/L'Etablissement public départemental de Clairvivre France 2002) - contains Clairvivre, l'utopie au présent, Archives de Clairvivre (2001) by Gabriel Peynichou, and La Cité sanitaire de Clairvivre.

La Passion de Jeanne D’Arc. DVD. (The Criterion Collection US 1999).

Vampyr ou l'étrange aventure de David Gray. DVD. (MK2 France 2007).

L’argent. DVD. (Carlotta Film France 2008).

Monte-Cristo. DVD. (TF1/Diaphana édition vidéo France 2005)

Credit Report

The film La maison du maltais (Henri Fescourt, 1929) is held in Archives Françaises du Film ( Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée). Tayar’s name is not credited, however, in a Cinémagazine interview with Aimée Barancy titled “Un quart d'heure avec Eliane Tayar,” she confirms her participation in the film (54).

Similarly, for the film Maldone (1928), which was directed by Jean Grémillon and is also held in Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée's collection, Tayar’s participation is again not certain, However in “L'archange et les vampyres” written by Barancy on Tayar in 1933, we read the sentence pronounced by Tayar “J'ai tourné aussi dans Maldone et me suis battue avec un clochard qui exagérait” [Trans.: I participated also in Maldone and I fought with a tramp who was going too far] (qtd. in Mazet 74).

The title La Cathédrale de Chartres is not certain, even if, according to Tayar's daughter, the documentary was centered on that monument (Forestier n.p.). While there is no evidence beyond the date, it could be the same La Cathédrale de Chartres produced by Caméra-Films in 1937. (See a June 1937 La Cinématographie française article entitled “Les principaux films documentaires et reportages filmés en 1935, 1936 et début 1937.”)

Secrets dans l’île was ultimately never made. The screenplay was published by Gallimard under the titles Secrets dans l’île in 1936 in the story collection Neuf et une, a collection dedicated to the winners of the Renaudot award (Mazet 35).

A handful of Tayar's later films are extant. These include four short non-fiction films, all held at Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, where she was assistant director: Le Roi Soleil (Jean Vidal, 1958), Quatre-vingt treize (Jean Vidal, 1964), La Fin d'un Monde (1965), and La Nation ou le Roi (Jean Vidal, 1965).

As an actress, Tayar had prominent roles in the silent films Embrassez-moi! (1928) and Amour et carrefour (1929), both considered lost. In Amour et carrefour, she was the leading actress. The film was produced by Les Films Célèbres and directed by Georges Péclet. In addition to Tayar, the other cast included Péclet, Roberte Beryl, Max Lere, and Manoel. In Embrassez-moi!, Tayar appeared as a secondary character. The film was written and directed by Robert Péguy and produced by Alex Nalpas. The cast included Suzanne Bianchetti, Hélène Hallier, Geneviève Cargèse, Prince Rigadin, Jacques Arnna, Henry Richard, Félix Barré, Ernest Verne, and Marcel Lesieur.

Citation

Vichi, Laura. "Eliane Tayar." In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2017. <https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-8d8b-8219>