Constance Bromley had a wide-ranging career as a stage performer, screenwriter, magazine editor, theater and cinema manager, and film publicist, work that took her across the globe. Her outspoken comments in the press on the influence of films from the West on Indian audiences, following her management of a cinema in Kolkata, have rightly given her a lasting notoriety in studies of Indian film and imperialism.

Bromley was born Constance Annie Jubb, in the Burley area of Leeds, Yorkshire, in the United Kingdom. She was the eldest daughter of the six children of draper George Bromley Jubb and his wife Sara Hannah (née Petty). Her maternal grandfather was John W. Petty, a prominent Leeds councillor and printer. Though she was known by the name Constance Bromley throughout her professional career, others in the family used the surnames Jubb or Bromley-Jubb.

Early on, Bromley had a passion for drama and literature, making her first theatrical performance locally in 1904 as a singer and reciter (“Northern Items”) before becoming a professional actress when she joined the touring company of theater-manager Herbert Beerbohm-Tree in 1905. Though she would never appear in a London production, she toured the English regions extensively, playing for Tree in “The Darling of the Gods” and as Iris in a famous production of “The Tempest” (“Manchester Amusements”). She moved on to touring companies managed by Charles Frohman and Edward Compton, the latter specializing in revivals of Restoration comedies (Culme). In 1909, she joined the touring company of Frank Benson, the precursor of the Royal Shakespeare Company, having by this time worked her way up from small parts and understudying to playing Olivia in “Twelfth Night,” Emilia in “Othello,” and Gertrude in “Hamlet” (“Social and Personal”).

Bromley wrote her first and only performed play, “The Ranchman’s Romance,” which was produced in Leeds in June 1906, with Bromley herself as co-lead (“Leeds Actress-Playwright”). It was not a conspicuous success, but its Canadian setting was an interesting reflection of her changing family circumstances. Bromley’s mother and siblings, but not her father, had emigrated to Canada, settling in Victoria. She joined them there in early 1912, having ceased theater tours of the United Kingdom in 1910 to spend a year in India with friends. After eighteen months in Victoria, during which she took part in and organized local stage productions, she returned to England, then set out once more for India (“Social and Personal”; “Fills Two Offices”).

She returned to England in 1913. According to the Canadian newspaper The Daily Colonist, she became involved that same year with Will Barker’s ambitious biopic of Queen Victoria, Sixty Years a Queen, her first known engagement with film. Her role in its production is not recorded, however, but it could have been her first foray into publicizing films. She also referred to screenwriting work around this time, evidence for which is elusive (“Fills Two Offices”). She may be the Constance Bromley who is credited as author of the Vitagraph two-reeler Twice Rescued (1915), though there is, so far, no record of her having worked in the United States (Twice Rescued).

Bromley re-emerges early in 1916 back in India as a stage performer with the Howitt-Phillips touring company, taking part in a production of Arnold Bennett’s “Milestones” in Lahore (“Milestones”). She was with the company the same time as Wheeler Dryden, Charlie Chaplin’s “lost” half-brother, whose existence at this time had yet to be acknowledged by Chaplin (Robinson 216-219). They do not, however, seem to have appeared together on the same stage.

That year, her career underwent two dramatic changes. First, Bromley joined and quickly became managing editor of the Indian weekly illustrated magazine The Looker-On, which was aimed at a British expatriate audience. (The journal included an interview with Wheeler Dryden in its January 12, 1918, issue, though this was probably after Bromley had given up the editorship [“Wheeler Dryden”].) Second, and for a while simultaneously, she became secretary-manager of a theater in present-day Kolkata (then known as Calcutta), the Grand Opera House (“Fills Two Offices”). This was converted, by new owner E. H. Du Casse, into a cinema that opened as the Bijou Grand Opera House in June 1917 (“Among the Picture Theaters”).

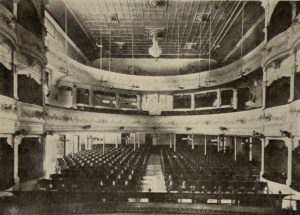

The Bijou Grand Opera House in Moving Picture World, February 1918.

The sumptuous venue seated 1,200 people, with stalls, dress circle, and twelve boxes. Its luxuries included marble flooring, a pipe organ, refreshment bars, an open-air terrace with a spraying fountain, and one hundred electric fans to soothe those seated in the stalls. Aimed primarily at the occupying British, indigenous audiences were restricted to the gallery, at least for evening performances. All attendees were catered to by “white-clad native” staff (“Films in India”). It was the very image of the British Raj. The films that Bromley ended up booking, for the Opera House and other cinemas in India and the Far East that were part of the same Bijou circuit, were exclusively American and British, chiefly obtained through the British distributor Phillips. Titles from the cinema’s opening weeks included Tatterley (UK 1916), The Ware Case (UK 1917), Camille (US 1917), and The Social Secretary (US 1916) (“The Theatre De Luxe of the East”; “Miss Constance Bromley”).

Bromley made a trip to London early in 1919 to undertake bookings for the Grand Opera House, but her employment with Bijou ended that year and she remained in Britain (Thacker’s [1920], Calcutta section, 117). It is at this point that she gave interviews and published a number of articles on film in India that were calculated to be controversial and have remained so (Arora; Burns; Mazzarella; Sharma). She began innocently enough in March 1919 with a lively, opinionated analysis of the Indian film business for the American journal The Moving Picture World (Bromley, “Too Much Competition in India”). But it was what she said in general British newspapers that was inflammatory. The first was a short interview given for the Daily Mail in July 1919:

The white woman in India realises that she is receiving less respect from the natives than before, and a great deal of this is due to the indiscriminate showing of films on social and marriage problems…The natives are great film enthusiasts, and there are 14 picture houses in Bombay alone. They will sit right through all the parts of a long serial film from dawn to dusk. The trouble is that most of the audiences are illiterate. The wording on the film is occasionally translated, but even then it is not understood. They, therefore, put any construction they like on the plot of stories, and get their ideas of European women inextricably mixed. They think of their own treatment of women and the rigid customs of law they have to obey. If the women go to the picture theatre they have to sit apart in a well-curtained box. The European women, too, are careful in their conduct, and are not seen in evening dress in public. And then comes the great contrast of the film, where the natives see white women in all sorts of garbs; on one occasion they saw the heroine of a long film, mainly garbed in a bathing costume. They see white wives on the screen in compromising situations, and the result is that they get a low opinion of European morals. (“White Women Films”)

The interview was read by many, aided by wide distribution through local newspapers that repeated Bromley’s words, particularly in the United States. She expanded on her theme of the “many undesirable films” that were “lower[ing] the prestige of the Englishwoman in Eastern eyes” in articles for The Evening News in September 1919 (Bromley, “Woman on the Film: The Position in India”) and the Daily Express in January 1921 (Bromley, “Firing the Train: Danger of ‘Third Degree’ Films in India”), both widely-read pieces. An informative interview for the film trade journal The Bioscope in October 1920 on the operations of the Bijou Grand Opera House turned into her by then familiar complaints about the presentation of white women, the supposed dangers of film serials shown to an illiterate audience (“some of the serials screened are the worst possible kind of stuff to give the native, and they don’t get it in homeopathic doses either”), and the need for greater film censorship in the British Raj (“Films in India”).

The Evening News article led to an interesting exchange in the pages of the Kinematograph Weekly between Indian musician Rajah Rham Singh, a composer of scores for Indian films, and Bromley. Singh stated that Bromley’s words displayed an ignorance of self:

Miss Bromley’s mem-sahib experience of India is very limited. No nation is perfect, and the average Englishwoman and the film actress are not immaculate or supernatural creatures…The gharri wallah knows the difference between the genuine article and the jumped-up imitation. He is no fool, nor is he illiterate because he is ignorant of Shakespeare and Charles Dickens…Miss Bromley must see her own country first, and then criticise others. (Singh)

Bromley replied that Singh had failed to understand the European mind: “In pleading for more moral films for India I do not defend European morals” (Bromley, “A ‘Facer’ for the Rajah”). This was both accurate and blind. Bromley’s arguments were aimed at two de facto camps. One was those who viewed American films in particular, and the industry that produced them, as requiring censorship to protect audiences from their perceived immorality. Such arguments would lead, in 1930, to the implementation of the Motion Picture Production Code, popularly known as the Hays Code, which set down moral guidelines for the production of motion pictures in America.

The other camp was the British Raj itself. British power in India had, by this point, passed its apex. Direct rule of the Indian subcontinent had been imposed by the British Crown in 1858. Indian nationalism, driven by British exploitation and administrative decisions that affected religious divisions, grew from the 1880s onward. It was greatly accentuated by the First World War and Gandhi’s campaigns of civil disobedience and non-cooperation. There were British moves toward eventual Indian representative government (Indian independence would be achieved in 1947), but there was much fear and resentment among the British living in India at the perceived threat to their way of life.

A focal point of change was the infamous Jallianwala Bagh, or Amritsar massacre, on April 13, 1919, in which many hundreds of pro-independence protestors were killed by British troops. Not only did this occur in the year that Bromley started writing her articles, but she specifically connected it with film censorship. She stated that it was only since Amristar that “any serious effort has been made to stop the exhibition of unsuitable films,” her implication being that some films, through their encouragement of “disrespect,” could encourage rebellion (“Films in India” 18e). For Bromley, cinema was an expression of the democratic threat the British Raj faced. She refused to see, or at least would not admit to seeing, that it was fear and not morality that governed her thinking.

Constance Bromley in the Leeds and Yorkshire Mercury, May 1906.

Given the perceived authority of the newspaper, nationally and internationally, Bromley probably made the greatest impact with her contribution to a special cinema supplement published by The Times of London in February 1922 (Bromley, “India – Censorship and Propaganda – Influence of Foreign Films”). Here, she praised the Bijou Grand Opera House as a bastion of censorship when it came to films that were “a travesty of Indian life and opinions” (she cited Alla Nazimova’s Stronger Than Death [1920], set in India, as an example). She claimed that interest in film censorship in India had been revived on account of “numerous articles,” in particular her own, though formal censorship was already in place following the Cinematograph Act of 1918, which introduced certification of films in India, managed by provincial Boards of Censors (Hunnings 223-224). She argued that “scores of unsuitable serial films still find their way on to the screens in hundreds of native cinemas, a first-class handbook to the teachings of Mr. Gandhi” and advocated for the government’s use of film as propaganda “to combat sedition-mongers.”

Critical discussion today on the issues that so animated Bromley, of “disrespect” to British colonizers and sexual licence in the cinema, views them as profoundly interconnected. For Miriam Sharma, cinema in British India became a highly contested area that exposed the limitations of empire. She argues that “the perceived need to guard against the revolutionary thoughts of communism and ideas from America that seemed to promote democracy and promiscuity fueled censorship as a major multivocal imperial policy” (41). For William Mazzarella, Bromley was typical of the British colonialists who were alarmed by the “eroticized egalitarianism” of cinema (63): “Bromley’s hand in raising the stakes of the moral panic of the 1920s is invariably noted by students of the period–hers is the one voice guaranteed to appear in any article on the topic” (82n5). This alarm was “inevitably diffracted through anxieties of empire and racial hierarchy” (65). He identifies a British colonialist ambivalence about cinema, at the heart of which lay a sense that Hollywood “had solved the global communicational puzzle by deploying a hypermodern technology to resonate with a savage sensorium” (66), meaning that film, as a medium that spoke to all people, needed to be controlled and exploited as part the British “civilizing mission” (63). Thus, calls such as Bromley’s both for film censorship and the exploitation of film’s potential for propaganda “were two sides of the same coin” (68). Mazzarella concludes that “movies in several ways laid bare the contradictions and tensions upon which colonial cultural politics were based” (81).

Bromley’s articles, and several from other correspondents making similar complaints, were considered by the Indian Cinematograph Committee (ICC), formed in 1927 to look at censorship and the promotion of British Empire films (Mazzarella 32). Contrary to Bromley’s hopes, the ICC’s 1928 report expressed exasperation at those who complained of the deleterious effect of films on morals without any empirical evidence to back this up. Instead, it found film censorship in India as it stood to be quite adequate (Barnouw and Krishnaswamy 56).

While producing her articles on film and censorship in India, Bromley found work as a publicist for British film companies. She started with Trans-Atlantic, managing film star appearances such as American serial star Eddie Polo when he visited the United Kingdom in 1919, and then moved to Granger’s Exclusives as publicity manager (“To Leading International and British Film Stars”; “Granger’s Exclusives, Limited”). She established an independent business in London doing star publicity under contract. This was bitty work, including temporary positions promoting individual films, such as the South African production King Solomon’s Mines (1919), which featured a lunch attended by the author Henry Rider Haggard (“Sir Rider Haggard on Films”), and publicity for the British film Adventures of Captain Kettle (1922) (“Service for Showmen”).

Such work dried up by 1925, a period of severe slump in the British film business. Bromley turned once more to the county of her birth, Yorkshire. The last of her Indian polemics was published in the Leeds Mercury in 1926, stirring up stale controversies in a regional rather than a national newspaper (Bromley, “Films That Lower Our Prestige in India”). Before then, she tried her luck once more as a writer of fiction, co-writing a dramatic serial of stage life, Doors of Destiny, with a former Benson and Howitt-Phillips actress Isabel Fladgate (“Behind the Scenes”). The thirty-part serial also appeared in the Leeds Mercury, in February 1925, before being syndicated across other regional newspapers. It enjoyed some success by being re-syndicated (credited to Bromley alone) across the United Kingdom and overseas up to 1933. A second serial by Bromley, The Isle of Romance, was published by the Leeds Mercury in August 1926. She wrote some occasional articles for the regional press, but her byline disappears after 1927. Her mother and sisters had returned to the United Kingdom from Canada by this time, living in Poole, Dorset, while Bromley herself, who never married, moved to Salisbury. She died there in 1939, aged fifty-seven.

Constance Bromley was a headstrong character, more determined than gifted in each of the many activities that she undertook, but her ability to seize the varied opportunities that came her way was remarkable. Her views of Indian cinema audiences, and her call for censorship, reflect the blinkered outlook of the British ruling class in India. Problematic as those opinions undoubtedly are, it is important for feminist film historiography that we study all aspects of women’s contributions to silent cinema, the difficult as well as the praiseworthy. Film in these pioneering years was such a stimulus to the imagination. It is that stimulus, and its expression in every form, that is our topic.