Helena Smith was born in 1883 and appended Dayton to her name upon marrying Fred Erving Dayton on June 26, 1905. Dayton began her career as a reporter at The Hartford Courant and described her transition into sculpting as follows:

In one day I did everything there from writing up the latest society scandal to the death of a whole family by gas, with eight hours of ordinary work thrown in. From reporting I went to writing for magazines, and [in early 1914] I was sitting at my typewriter, when my fingers began to itch for something to mould, though I didn’t even know what artists’ clay was, and had never seen an artist or sculptor at work (“Caricatures in Clay Are Her Contribution” B12).

Equipped with nothing more than copious amounts of clay, nimble fingers, a sharpened match, a hairpin, and “an incorrigible sense of humour,” Helena began crafting hundreds of eight- to twelve-inch tall statuettes inspired by “modern city life” (“Cartoons in Clay by a Woman” B7). Lining the many bookshelves of her brownstone residence at 313 East 18th Street in New York City, these water-colored clay figures would ultimately play starring roles in some of the earliest known works of stop-motion clay animation.

In the second half of 1914, only a few months after the start of Dayton’s foray into sculpting, numerous articles written in celebration of her innovative and “delightfully grotesque” (“Caricatures in Clay Are Her Contribution” B12) figurines began to pop up in the likes of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the New York Tribune, and the Richmond Times-Dispatch. These articles reveal many crucial aspects of Dayton’s creative process, including her extensive background in dance, which endowed her with a trained eye for human anatomy and movement. The numerous photographs and vivid descriptions of Dayton’s sculptures lining the pages of such articles also attest to the breadth of her subject matter: not only did she craft models of “fashionable society leaders” to be showcased in “many of New York’s finest palaces,” but she also parodied classical art with a “pensive salamander” in the style of Rodin’s The Thinker, and exhibited a willingness to forsake realism through creations such as a slack-jawed, anthropomorphized lighthouse (“Fashionable Society Leaders in the New Clay Cartoons” S6).

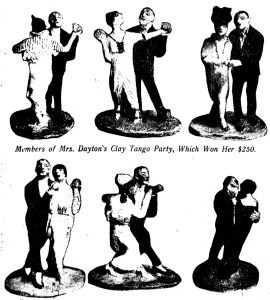

An announcement dated January 16, 1915 in the popular humor magazine Puck marks the start of what became an extremely lucrative year for Dayton:

Mrs. Helena Smith-Dayton, wonder-worker in clay, carries off Puck’s $250.00 for the best cover submitted before January 1. Her entry in the prize contest [“Tango Party”] is by long odds the quaintest conceit that has come into the Puck sanctum in many moons. So original, so strikingly new in conception is it, that we felt obliged to repress a natural impulse to print a black-and-white reproduction of it on this page. We prefer to let the cover speak for itself upon its appearance February 6, in order that your surprise may be as complete as ours, when the cover was first show to us (“What Fools These Mortals Be!” 3).

In the same issue of Puck, Dayton debuted a recurring comedic series, “Mrs. Canary’s Boarding House,” which she wrote and illustrated with photographs of her clay figures. She began copyrighting some of her sculptures (“Works of Art” 450-451), attracting local artists to her weekly Sunday studio salons, and establishing herself as a frequently reported upon somebody within the flourishing Greenwich Village art scene. By year’s end, Dayton netted more than $12,000, as detailed in a New York Tribune article patronizingly titled, “Woman’s Place, If You Insist, Is in the Home; but Who’s Going to Fuss About It If She Wants to Earn $10,000 Or So a Year Somewhere Else?” As Chairwoman of the Art Committee of the Empire State Woman Suffrage Party, Dayton applied this commercial savvy to organizing fundraisers that featured her artwork before the unsuccessful statewide referendum in November 1915.

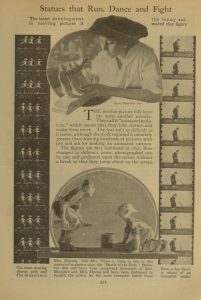

With a considerable amount of capital at her disposal, Dayton began developing a photographic means by which to animate her characters of clay. Despite the common misconception that Dayton’s first (or only) film was the one-reel Romeo and Juliet, which was distributed by Educational Films Co. in the fourth quarter of 1917, the earliest documented screening of her shorts actually occurred at the Strand Theater half a year earlier, on March 25, 1917 (“Latest Picture Novelty” 58). It remains unclear exactly when she started to experiment with the technique she called “stop action,” though in the same year Dayton recounted, “the difficult thing at first was to determine just how much to move an arm or a head, to avoid an appearance of jerkiness. I used to make the changes too great, but am learning to overcome that now” (“Romeo and Juliet–In Clay!” 434). The two reviews below, both concerning Dayton’s untitled films shown at the Strand, shed a glimmer of light on the impact of her technique on audiences:

Helena Smith Dayton’s animated sculpture was a weird and amusing picture, quite baffling to the lay mind (“On the Screen” 11).

Animated sculpture is the best novelty in motion pictures. It owes its existence to Helena Smith Dayton, a New York sculptress of note. The method employed in making the Animated Sculpture films is similar to that of animated cartoons. The figures are first modeled in clay, then changed to different poses, photographed one by one and projected upon the screen, showing them jumping about as if they were real. The effect is highly amusing […] (“Sparks from the Reel” C13).

In the months between her theatrical debut at the Strand and the wintertime release of Romeo and Juliet, Dayton juggled her participation in a large independent art exhibition at Grand Central Palace, suffragist parades and fundraisers, and the continued production and release of comic films. The various strands of her professional and personal life appear considerably interwoven during this period. For example, one of Dayton’s films, produced by the S.S. Film Company of New York, seems to have been shown to Governor Whitman at a suffragist fundraising event on August 29 (“Animated Sculpture Appears” 546); Pride Goeth Before a Fall (1917), her short which concluded Pathe’s Argus Pictorial No. 2 program, featured “dances and other stunts” (“Pathe’s Argus Pictorial No 2” 1523); Dayton’s miniature statues of actor George M. Cohan were on display in the Strand lobby during the theatrical run of his film Broadway Jones (1917) (“Statues of Cohan” 175); and a description in Moving Picture World of her contribution to Pathe’s Argus Pictorial No. 3 program–starring “clay figures around the banquet board”–is reminiscent of a banquet scene from Dayton’s aforementioned recurring series in Puck (“Items of Interest” 1774).

Much of what is currently known about Romeo and Juliet comes from a full-page review in Film Fun from November 2, 1917. Three stills from the short film are accompanied by the uncredited author’s confession, “when the immensity of the thing had dawned upon us, we hustled over to the studio to find how the wheels went round.” To the interviewer’s surprise, Dayton confesses, “there are no wheels and no strings.” Special attention is drawn to a ballroom scene in Romeo and Juliet containing thirty moving figurines, no small accomplishment for an independent animator even by today’s standards. The image of a bug-eyed moon spying on Romeo beneath Juliet’s vine-covered balcony reveals a busy mise-en-scene and asymmetrical composition. Clay figures are draped in elaborate costumes, and each shot incorporates a belabored use of shadow (“Romeo and Juliet–In Clay!”434).

While various sources suggest that Romeo and Juliet was produced and/or “filmed” (at least in part) by the S.S. Film Company (“Animated Sculpture Appears” 546), distributed by Educational Films, and made “under the guidance of J. Charles Davis, Jr.” (“Prominent Sculptor in Film” 1164), calling into question both the extent of Dayton’s financial investment in Romeo and Juliet and whether or not she operated the camera, a reviewer for Moving Picture World noted that the film actually begins by showcasing Dayton’s authorial role and creative process:

Little need be said here of the wonderful talent of Helena Smith Dayton: her work speaks for itself. In the introduction to the picture we are privileged to watch her deft fingers fashion the form of Juliet from an apparently soulless lump of clay. This mere lump of clay under her magic touch takes on the responsibilities of life, and love, and sorrow which the play requires, and finally grasps in desperation the dagger with which it ends its sorry life, falling in tragic fashion over the already lifeless form of its Romeo (“Prominent Sculptor in Film” 1164).

In addition to appearing onscreen as herself in Romeo and Juliet, Dayton reportedly also wrote “the clever jingles which sub-title her pictures,” according to the Film Fun coverage of the film (“Romeo and Juliet–In Clay!”434).

Despite being well covered by a variety of media outlets, and despite her ambitious plans to create more shorts for Educational Films at the rate of “one picture a month” (“Romeo and Juliet–In Clay!” 434), Dayton’s career as a stop-motion animator was unfortunately short-lived. A few months after achieving the right to vote in New York, in November 1917, Dayton took up a new cause by relocating to Paris to manage a YMCA canteen for soldiers. Upon her return to America after World War I, Dayton pursued work as a columnist, novelist, playwright, and portrait painter, but never again, it seems, as an animator.

At present, Library of Congress records contain no mention of Dayton’s films or copyrights for those films. Online searches through the websites of several prominent American film archives return no results for her name, the few known names of her shorts, or the Argus Pictorial reels. The apparent absence of her films from the archive–a consequence of, at least in part, her gender, her chosen medium, the brevity of her career, the small scale of her productions, and the limited distribution afforded to her films–may continue to drive Dayton into the margins of early animation history. However, the sheer volume of words penned after screenings of Dayton’s stop-motion animation testifies to the magnitude of her impact on New York City audiences. The absence of Dayton from most influential histories of animation, then, speaks to the need for scholars to look beyond extant films when it comes to writing film history. The rich variety of reviews of–and photographs from–Dayton’s productions can easily serve as a launchpad for further research and analysis, and the timing of Dayton’s career places her contributions in direct dialogue with exalted American contemporaries such as Willie Hopkins and Winsor McCay. With any luck, such research may lead to the identification of one or more of Dayton’s innovative animated works.