Daisy Sylvan—the producer, director, and star of two motion pictures, both lost—was born Elena Mazzantini in Rome. She moved to Florence, where she started a film production company, Daisy Film. In 1920, she became the widow of her husband, Francesco Rosso, and the beneficiary of a retirement fund, as we can infer by the registry office certificate only discovered recently (Pepi 2008, 11). Her education is still unknown, though she was not a Florentine nor an aristocrat, as has been erroneously reported by sources until today (Strazzulla and Baldassini 1995-1996, 25-27; Martinelli 1998, 47).

In fact, she was legally separated from her husband, having married in Rome in 1897, by the judgment of Florence Courthouse in September 1902, according to the Civil Registry and Graveyards Archive of the city of Florence (Pepi 15). After the completion of the two motion pictures in Florence, the only two produced by her company, all trace of her was lost.

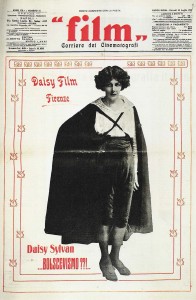

The first press mentions about Daisy Film, established with legal domicile on the very centralized Via Strozzi 1 at the end of 1919 (Martinelli 1998, 47), is the publication of an announcement in L’Arte Italiana Giornale del teatro e del Cinematografo on April 25, 1918: “Two wonderful scripts have already been written, one of which set in Russian location with traditional costumes. A beautiful lady, who possesses all the quality to become a good and sublime actress as well, will be the protagonist” (Cardini 1918, 3). The script quoted by the journalist Gino Cardini is evident: we are talking about …Bolscevismo??/Bolshevism??, whose shooting was concluded before June 10, 1920, according to an ad that appeared in Film in 1920. …Bolscevismo?? is a work that Italian film history knows because of a harsh journalistic controversy that may have been the reason the film was not distributed: “The base seems to be union nature matters: the critic Giuseppe Lega gets to accuse Daisy Film of anti-union behavior towards society’s personnel, suddenly fired for unclear reasons. Daisy Film strikes back with great announces on all the specialized press, précising that, on the contrary, the reasons were grave and plausible, and it presents a legal action which consequently leads to a counteraction… After that, no one heard anything about the movie and it is reasonable to doubt that it has ever been presented to the audience” (Martinelli 1998). But Giuseppe Lega was not just a critic: in 1924 he directed Piccola Monella/Little Brat, sold in France, Belgium, and Great Britain.

In 1920, Lega founded the fortnightly review L’Arte del Silenzio/The Art of Silence in Florence, whose management, in 1921, was passed to Paolo Azzurri, founder of the school of acting of the same name, first in Palermo and then relocated to Florence, in an ancestral building on Via Cavour. In 1920, Azzurri directed the film Il Soldato cieco/The Blind Soldier, produced by Azzurri Film (and financed by the National Pro-Blind Institutions Federation), performed by the students of the school and presented in every Italian city. What seemed to be a journalistic controversy appears, in fact, to have been a turf war between producers and actors-directors (Azzurri had debuted as an actor at The Ambrosio in Turin in 1908). Sylvan, Azzurri and Lega had, each one of them, to defend their personal interests, which explains the legal actions taken as well as the delinquencies Sylvan was accused of as a producer.

But the city’s acting schools appear even more at the very center of Sylvan’s production adventure if we consider that, at that time, the most prestigious of them was the Florence School of Acting, founded by actor and theater historian Luigi Rasi in 1882. Rasi managed the school until his death in 1918, the very same year production of Sovrana /Sovereign began. His teaching emphasized a naturalistic style of acting. Rasi was the most important male actor in Sovrana, which, according to the leading actress, director, and producer of the movie, was completed in April of 1920 (“Conversando con Daisy Sylvan,” 1). Of both these lost works, the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze stores two commercial pamphlets, printed in Rome and void of date (edited by Daisy Film dealer, A.M. Capasso, located in Via Gregoriana 5, Rome), which contain accurate synopses of the motion pictures, set photos, and Sylvan portraits. The first line of the description of Sovrana, adapted from a theatrical comedy by Dario Nicodemi, states: “Giana, with no family, is saved from the underworld by the great actor Luigi Rasi and launched through the glorious paths of the art.” Considering that the Florence Courthouse ratified the legal separation of Elena Mazzantini in 1902, the most reliable hypothesis is that Daisy Sylvan was an “artistic creation” of Rasi himself: presumably she was an apprentice “saved” from a disreputable life (at that time, the say-so of the Sacra Rota was necessary in order to obtain a legal separation).

Contrary to what was thought until that time, a careful reading of the synopsis contained in the pamphlet of …Bolscevismo??, held at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, presented by several ads as a “cinedramma di avventure” [dramatic adventure film] (Film 1920, 5; Contropelo 1920, 3), highlights the structure of a morality play, with “social life violent scenes” (Baiardo 1920, 14), whose central theme is love of work. Talking about it in the only interview she granted, Sylvan defines it, “a great moral and social motion picture,” adding, “I wish to develop novels not only consisting of a storyline, but involving moral and social content, taken from real life. Cinema must have an educational purpose as much as theater” (“Conversando con Daisy Sylvan,” 1). The pamphlet introduces the film with the sentence, “We can achieve Good through nothing but Good itself: which is Love – Duty – Work.” The narrative scheme is resolved in a battle between Good and Evil, in which Sylvan interprets the double role of Elena Morgani, who represents Good, and her sister Enelia, who represents Evil, though both are burdened by the vicious journalist with the adventurous and exotic name of “Zobisant” (in the set photos he is portrayed with Lenin’s Mephistophelean goatee), an “ill-omened man who already once spread the pain of Elena Morgani’s soul for evil passion.” Elena, a “flower of beauty and goodness” is a hard-working woman who, from her office, of Work and Homeland, guides “the industriousness of the industrious village,” Selenio (a reference to the Goddess). Zobisant persecutes the two sisters (the evil one stole the other one’s husband) because he has been harboring hatred “during the years of absence spent in a Country which has been made barbaric by internal fights and revolutionary disorder.” Zobisant is the real Bolshevik, the personification of Evil. On the other hand, Elena accomplishes quite another kind of revolution, which is fulfilled in the finale, when, after many misadventures, “She stands there, despising the danger she is exposed to, and dominates… dominates… ‘Bolshevism???'” An instant later, Zobisant has fallen to his knees at her feet, begging for mercy and forgiveness. The final sentence of the pamphlet’s description of the film ends the morality play with the necessary victory of Good: “The Evil that passes, swamps but does not destroy: it restores the blooming forces to the right and holy fight of right and duty.” Even the complex sentimental storyline of Sovrana, defined by La Nazione as “a delicate and interesting plot on the suggestive background of the majestic Florentine beauty” (3) ends with the protagonist’s final victory. Giana (an allusion to the two-faced divinity, but in its female inflection), rejects the insisting avances of a prince, who is a beau of hers: “victorious, she is the sovereign of her heart.” Separated, with an adult son obliged to take her defenses during an argument (L’Arte del Silenzio 1920, 4), but educated at the Rasi’s school, Elena Mazzantini attempts the adventure of artistic emancipation by producing, directing and acting in two motion pictures. However, Paolo Azzurri’s campaign against her proved to be a major obstacle for Mazzantini’s artistic endeavor. The pamphlet of …Bolscevismo?? describes very carefully how Zobisant orchestrates a libelous campaign against Elena Morgani, playing her own employees against her, spreading distrust and dissatisfaction towards her, while “under the ruins of the disasters that the evil ones carry out all over the Country, the innocent victims are amassed without any remorse.” The first page of the pamphlet presents the film as based on the novel La fiamma nella steppa by Danilo Korsakoff, a Russian exile, according to Martinelli, “adapted to a different kind of environment” (1981, 20).

...Bolscevismo?? was shot in the Florentine villas and in vividly realistic locations, including miserable hovels (Baiardo 14), likely because Daisy Film possessed a just barely passable studio (Cardini 3). The film seems, in fact, to reread the adventure set in Russia with traditional costumes in a more private, intimate way, including traces of the real production conflicts which animated this cinematographic endeavor. Furthermore, Florence, artistically speaking, was a hostile environment. However, in spite of that, they succeeded for a short time in that town. The Elena portrayed in ...Bolscevismo?? fights for “justice, right and duties;” the Elena the magazines of the time refer to, often by the denigrating epithet “Lady,” is the tyrannical ruler of Daisy Film who repeatedly laid off workers without notice: after all, we find numerous signs of mysterious personnel alternation in reviews in Film. An article of the controversy (Azzurri 1920) reveals that Azzurri rented Sylvan some cameras, provided Kodak film stock, and directed photography on behalf of her. His son, Natale Azzurri, the operator of Daisy Film who abandoned the set (or was fired, depending on the version) was substituted by Luigi Martino, of the Roman company Guazzoni Film, which provided Daisy Film with technical and artistic personnel after the layoffs. From that moment on, the battle blustering in L’Arte del Silenzio was covered by all of the main film publications. It is fair to suppose that the dispute was not really about anti-union behavior, but rather about the fictional motion picture that alluded frequently to reality to substantiate Sylvan’s side of the argument with Azzurri in the audience’s eyes: an unbiased media confrontation, Cinema versus Press, transfigured into a fantastic narration cast into a physically recognizable universe of everyday objects and landscapes.

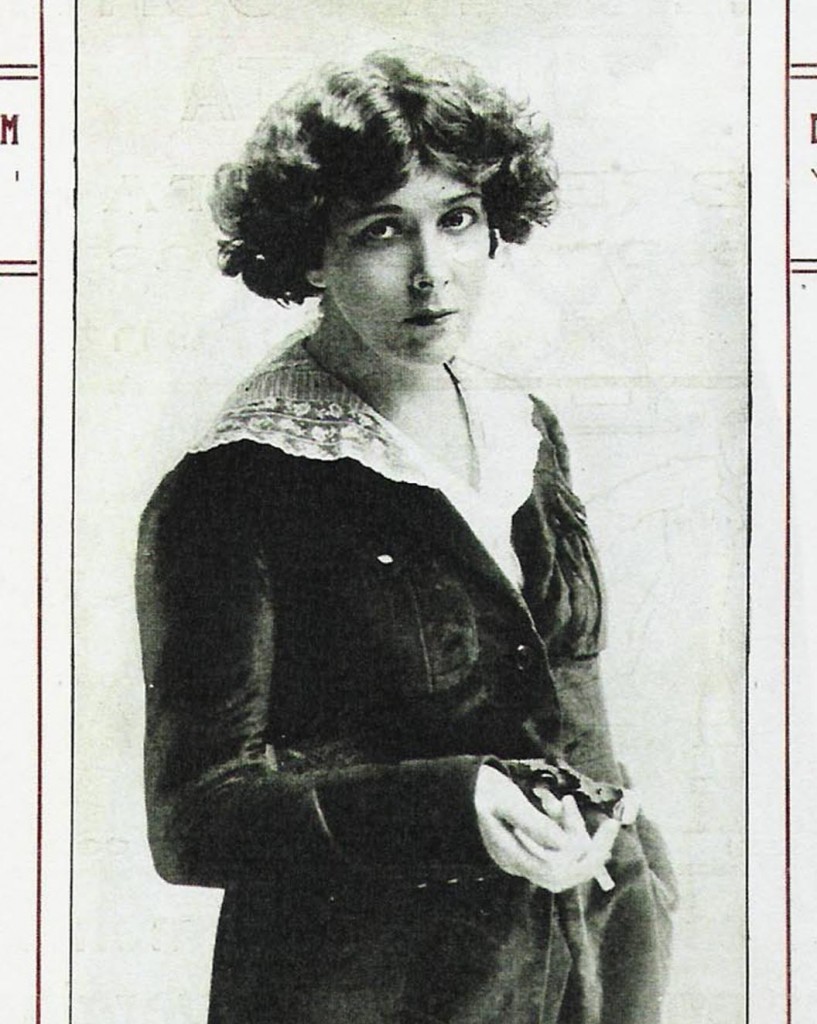

Therefore, in the fiction, the beautiful Elena wins the “arm wrestling” contest against Zobisant; in reality, Azzurri surely gained the upper hand by attacking Sylvan in public, accusing her of dishonesty and tyranny (Azzurri 4). Sylvan filed a complaint for defamation (Kines 1920, 3). The movie, after a private showing in 1921, which was only reported by the fortnightly Febo Periodico bisettimanale d’arte, spettacoli e mondanità, appears not to have been distributed. …Bolscevismo?? gained the censorship’s stamp on March 3, 1922, after making cuts to a scene “in which we can see two violated woman struck down to the ground” (Strazzulla and Baldassini 25-27), and in 1923 was given to Turin by Itala Film on behalf of U.C.I. to be distributed. Indeed the title appears quoted in a letter from a functionary of U.C.I. who asks Itala to recover and send to Rome several hundred posters of the motion picture, printed in Turin by the Buttery society at Via Mantova 45 (Carteggio UCI-Itala Film, n.d.). So this film, as many others, though distributed, was never shown in theaters. The same fate befell Sovrana, which constituted, along with ..Bolscevismo??, a sort of “package.” Hundreds of other films languished in the same obscurity, stowed in warehouses of the bankruptcy consortium Unione CInematografica Italiana. Eventually, the only documents we can use to reconstruct the first film remain the commercial pamphlet and the anonymous review that followed the private showing in Rome, not examined by historians until now because it was published in an artistic magazine (repr. in Pepi 2008, 259-261). The columnist claims that he attended the showing with a “very restricted number of friends.” The event appears “new” to him, “partially human and partially adventurous,” “elegantly, modernly, detail-oriented” staged. But his attention is focused on the leading actress’ execution, playing two different parts, “unrecognizable between one and the other,” author of a splitting accomplished “with marked and distinct psychological characters, with a different set of movements, with a complete substitution of attidutes [sic], expressions, gestures” (“Una visione private di ‘Bolscevismo’” 3). Elena and Enelia Morganti, but also Elena Mazzantini and Daisy Sylvan, represent the different souls of a leading actress, director, and producer, whose films have not survived. However, several portraits attributable to ...Bolscevismo?? still exist, the most amazing of which remains a full shot of a woman with a pants suit tight under the knee, ankles exposed, short frothy hair à la Clara Bow, white starched lace collar and hands in the pockets: it portrays a radiant working girl who, as a cinematographic character, only 1940s American Cinema would be able to completely define, that is, socially validate (Pravadelli 2007, 157-194). From the top of her affiche, Daisy Sylvan smiles, looking happy and a little spiteful, questioning us (Gaines 2008, 19 – 30).