While existing scholarly and documentary efforts are obsessed with naming Li Minwei (黎民偉) as the founding father of Hong Kong cinema, the contributions of female figures like his wife Yan Shanshan—except for being fetishized as the legendary first Chinese film actress—have been largely overlooked. On the other hand, while contemporary feminist film scholarship strives to recover the history of women working behind the scenes, the act of being in front of the camera in the particular historical and cultural context of early twentieth-century China cannot afford to be ignored. Yan’s role as a pioneer in Chinese film history thus not only derives from her involvement in business matters at her husband’s film companies, but also from the mere fact that she displayed her body, with an uncertain degree of willingness, in a new, and public, medium.

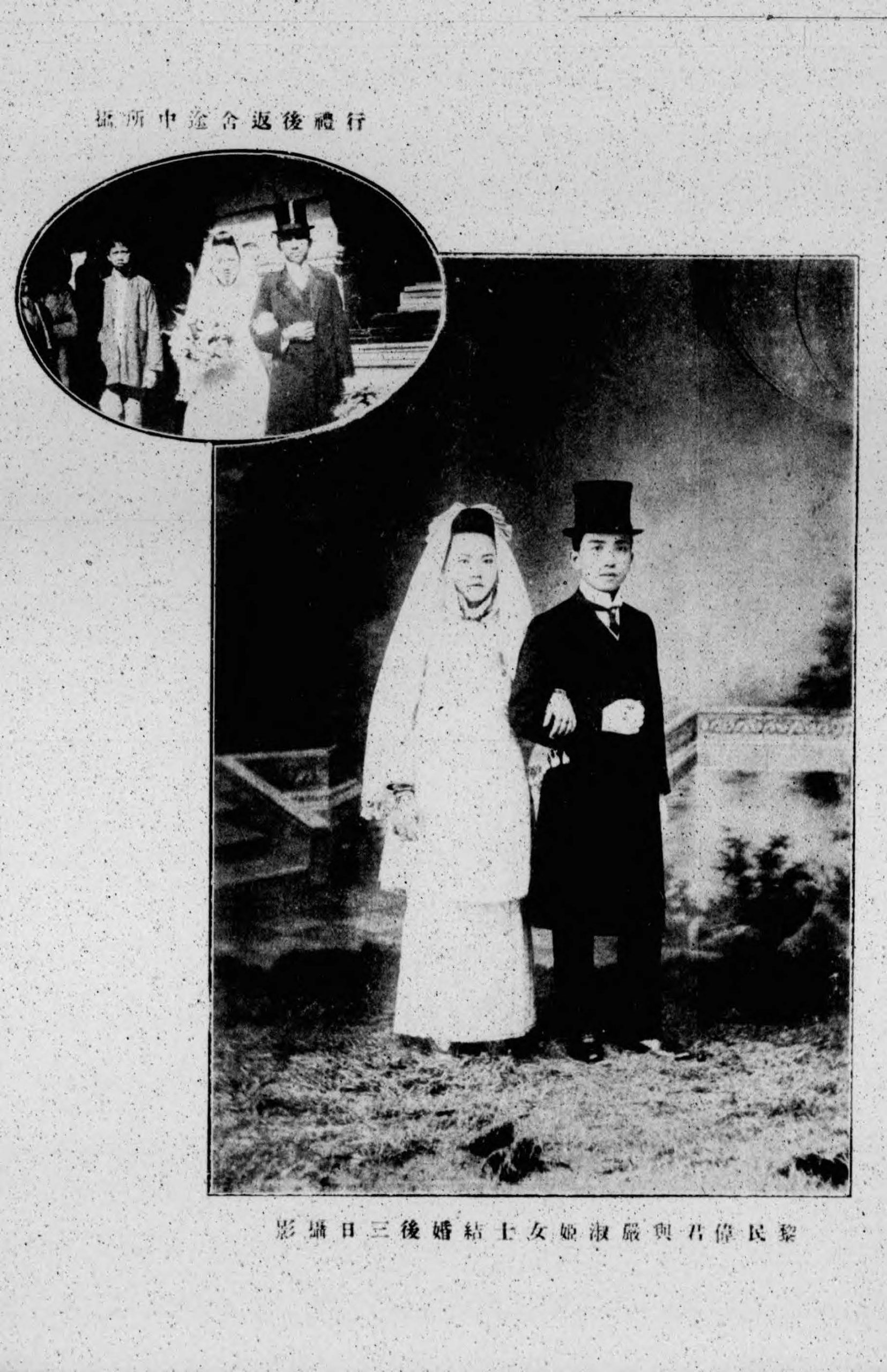

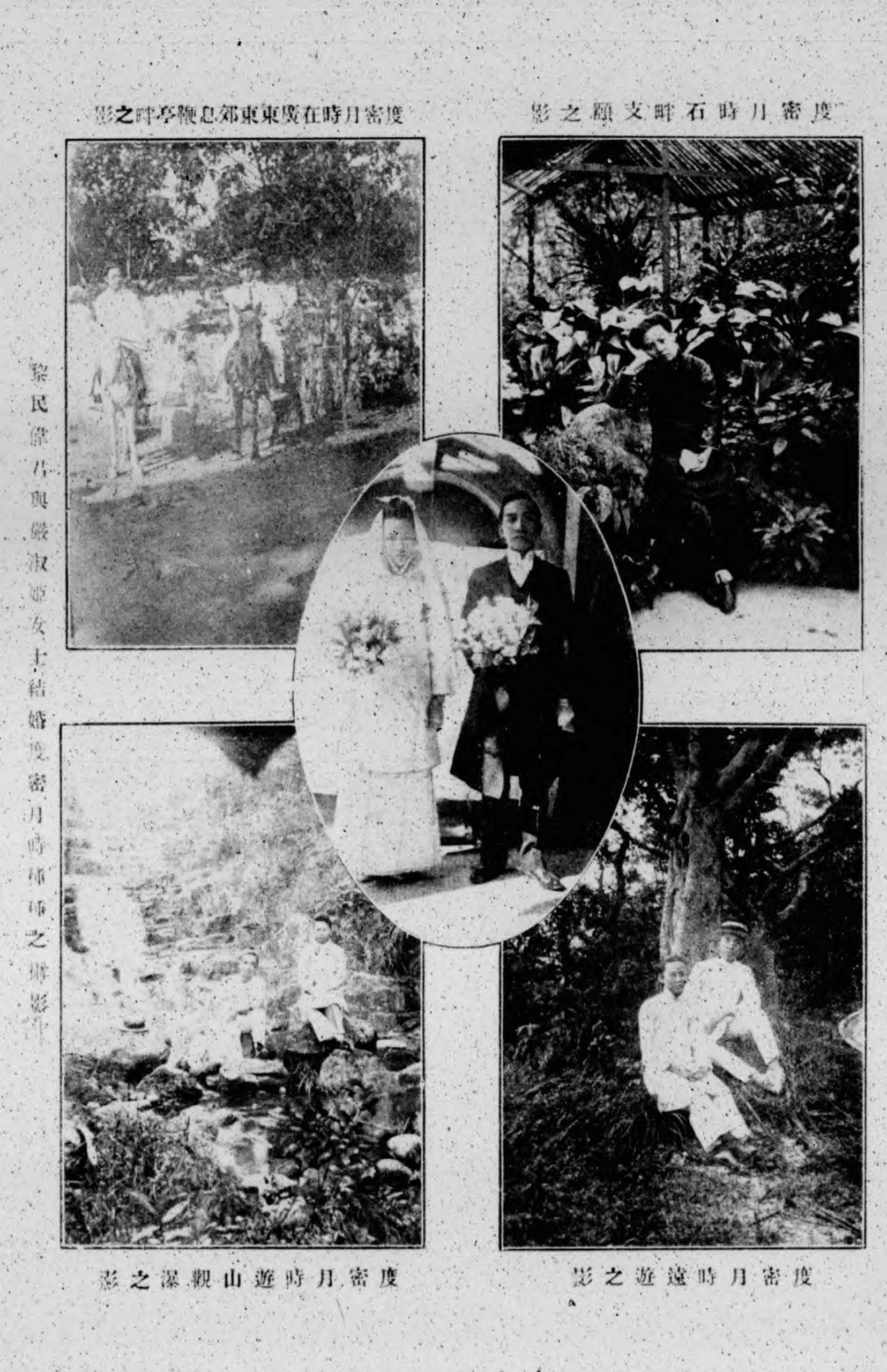

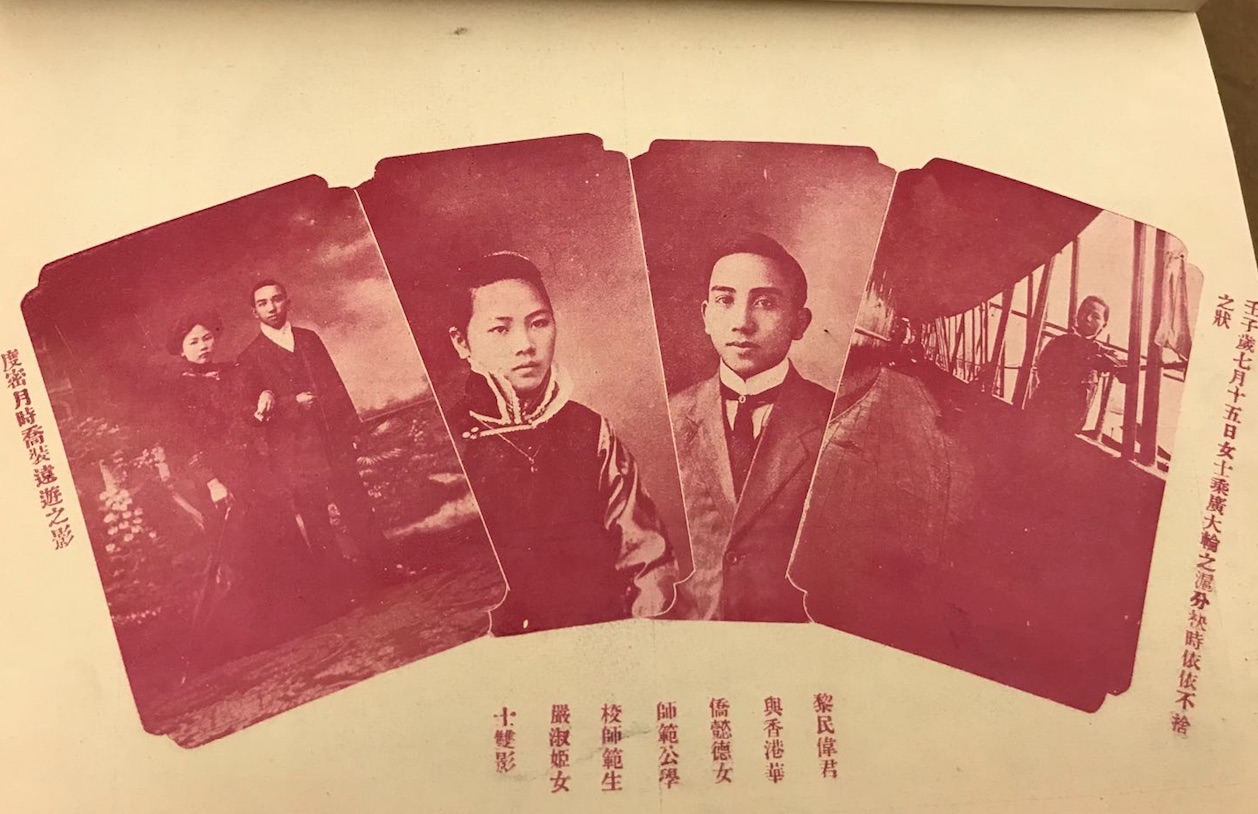

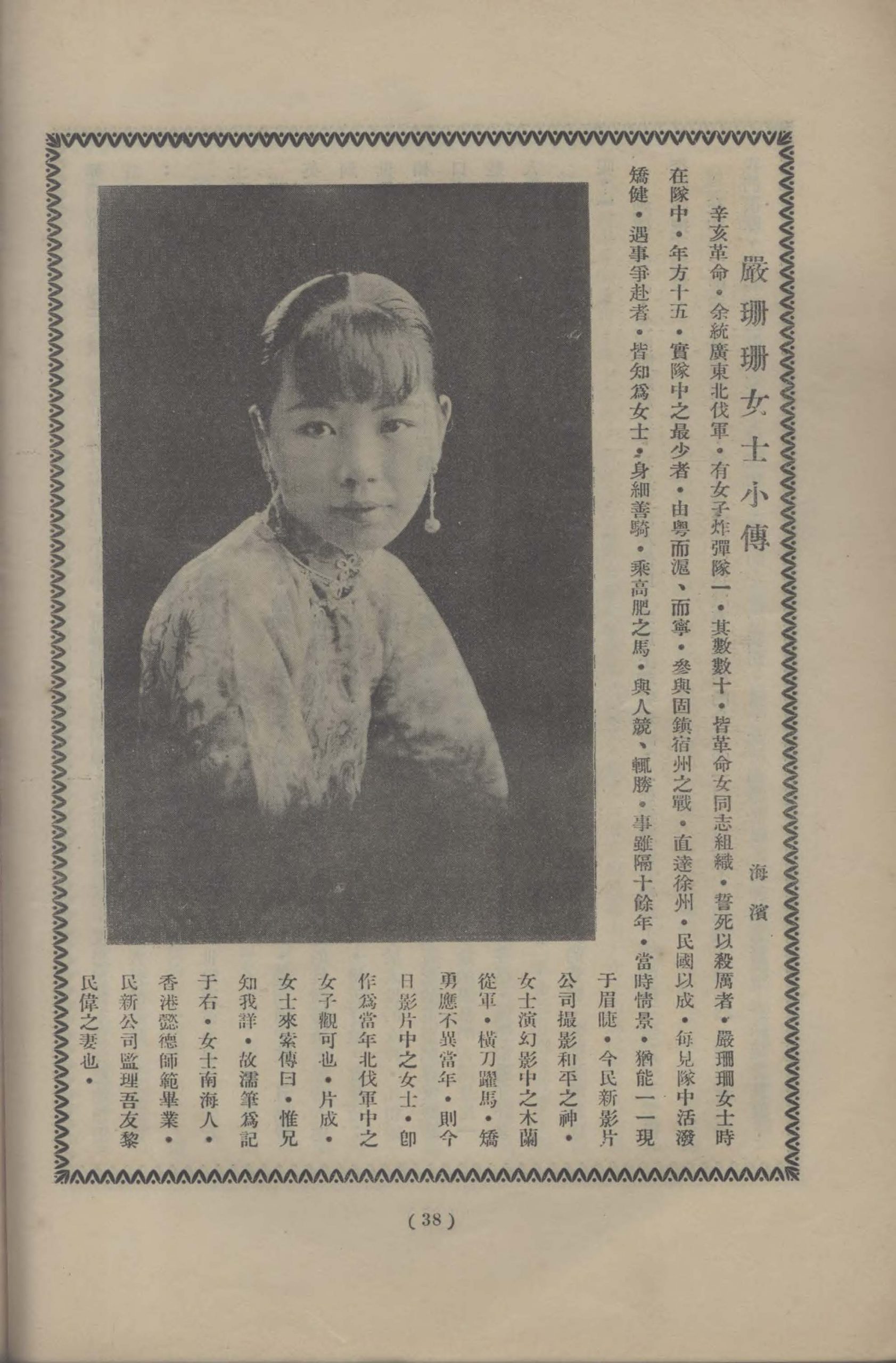

Born Yan Shuji (嚴淑姬) in Nanhai County, Guangdong Province, at the end of nineteenth century and the twilight of the Qing dynasty, Yan was among the first generation of Chinese women to obtain a modern education. The earliest public information about Yan that I am able to locate under her birth name Shuji (lit. virtuous/fair lady) appears in Women’s Times/婦女時報 in 1914. A photo insert features images from Yan and Li’s wedding and honeymoon, showcasing her Western-style wedding dress and their modern lifestyle with honeymoon travel. A caption also references Yan’s status as a student at the Hong Kong Overseas Vernacular Yide Normal School for Women (香港懿德女子師範學校). Before her marriage, in March 1912, the then fifteen-year old Yan joined the first-aid team of Guangdong’s North Expedition army at the dawn of the Xinhai Revolution and did rescue work in Nanjing and Xuzhou for several months (Li 2003, 4). In 1926, Zou Lu (aka Zou Haibin), the leader of the revolutionary army and later a Guomindang high official, wrote a short piece for Minxin Special/民新特刊 in memory of Yan’s bravery, agility, and youth, recalling how she was adept at horsemanship, a skill that came in handy when she played Mulan in The God of Peace/和平之神/heping zhi shen (1926) (38). Yan’s remarkable horsemanship was also a valuable asset behind the scenes. On July 22, 1926, Shen Bao/申報 published an article about how, during the production of The God of Peace, a horse-riding Yan rescued a friend who fell from a startled horse right in front of an approaching car (23).

In either 1913 or 1914, Yan became the first woman in China to perform onscreen when she played the servant girl in Zhuangzi Tests His Wife/莊子試妻/zhuangzi shiqi. (Scholars have not reached a consensus on the year of the film’s production and release.) She appeared alongside Li, the writer of the film, who cross-dressed as the wife. Female impersonators were the common practice in Imperial China since actresses were viewed by the public as comparable to prostitutes. The stigmatization of the actress’s body did not dissipate with women’s increased public visibility onscreen as China transformed into the Republican era. Consequently, as Yiman Wang powerfully argues, contrary to the conventional argument that writing—an assumed sign of female authorship—entails more agency than performing, in Republican China, acting proved to be a more politically provocative and precarious profession for women like Yan (2011, 244). The suicides of Ai Xia (艾霞) and Ruan Lingyu (阮玲玉) in the 1930s testify to the precarity of acting as a profession for women, which may help, in retrospect, to explain the phenomenon of Chinese actresses retiring from film en masse in the late 1920s. Yan was but one of them.

Apart from acting, Yan was involved in the financial matters of her husband’s film companies, though this often took the form of domestic labor. According to film director Ouyang Yuqian (歐陽予倩), Li Minwei’s Minxin Company (民新公司) was a family business created by two friends, Li and Li Yingsheng (李應生), whose wives, it seems, were also involved in company business. According to Ouyang’s memoir, “[There are] two bosses, three official boss ladies—Li Yingsheng’s wife, Li Minwei’s wives Yan Shanshan and Lin Chuchu (林楚楚)—and another intimate lady friend of Li Yingsheng, Xu Yingying (許盈盈). They are all bosses” (1984, 2). Little else is known about Yan’s role as “boss” here. In the context of Ouyang’s memoir, the term “boss” (老板/laoban) may have meant business owner, especially considering the nature of family business in which everyone was involved, and private funds were often used for the sake of the public entity.

After the founding of Minxin Film Company in 1925, Yan retreated off-camera, while Li’s second wife Lin Chuchu became one of the main actresses for the company. Entries in Li’s diary document how Yan took charge of financial matters in Hong Kong on behalf of her husband. In 1926, she dealt with a debt crisis while Li and Lin were shooting in Shanghai. For example: “27/3/1926 – Lily [Yan] goes back to Hong Kong by sea to handle the problems of World Theatre shareholding and a bank overdraft of 27,000 dollars [yuan] to first brother Hoi-shan” (10). Yan again oversaw financial matters for the film company in 1930 when she had to cable Li saying that “the money is barely enough for the [Lunar] New Year expenses” (13). Yan was, at that time, facing the Hong Kong creditors’ pressure for repayment alone in Shanghai while Li was shooting He’s Back from the Jailhouse/故都春夢/gudu chunmeng (1930) in Beijing. She acted as mediator between Li and his business partner Li Yingsheng, who refused to help them out with the crisis initially, but eventually lent them 2000 yuan after negotiations (12). Given Yan’s experience with financial matters, it is not surprising that after the destruction of another of Li’s film companies, Qiming (啟明) Studio, by Japanese bombardment in 1942, she accompanied Li to visit the director Chen Junchao (陳君超) with a request to “solve the livelihood of Qiming employees” (24). Yan’s financial and social activities remain sparse in the published diary, but we are still able to trace the important role she played to keep these film companies running.

In addition to her pioneering status as an early actress and her involvement behind the scenes in financial matters, I contend that Yan is also important through her relationship to actress Lin Chuchu. In a still-polygamous society, a man like Li Minwei was expected to have more than one wife, and his diary details how proactive Yan was in picking Lin as his future wife, inviting her to stay over when he was away, negotiating with Lin’s parents, and arranging the bride-price with his father (6). With Yan’s matchmaking, Li and Lin were married in 1920, and a few years later, Yan and Lin appeared together in several films produced by Li’s company, such as Rouge/胭脂/yanzhi (1925), The God of Peace, and Five Revengeful Girls/五女復仇/wunü fuchou (1928). Given the blurred boundary between family life and business, as well as domestic and public labor, it is important to challenge the view of Yan’s matchmaking as merely a residue of the premodern, polygamous culture. In fact, this personal relationship could invite a speculative reading that sees Yan as Lin’s scout and an unofficial agent for both Li and Lin. That is to say, in bringing Lin into the family, Yan discovered and nurtured a major star in the Chinese film industry and, in so doing, managed to extricate herself from appearing onscreen after 1928.

The elliptical evidence of Yan as an influence behind the camera speaks to the complexity of understanding domestic labor in both the archive and traditional historiography. Breaking the taboo of women performing in public onscreen, handling financial crises for her husband, and potentially fostering a young actress to become a star, Yan presents challenges to a woman pioneer model that privileges creative labor behind the scenes in the traditional sense. Her life and career call for a more contextualized way of thinking about female agency in early cinema in relationship to specific national industries and cultural formations.