Although best known as the premiere Hollywood gossip columnist of the classical Hollywood studio era, Louella Parsons began her career in the film industry in 1911 when she was hired by the Chicago-based production company Essanay as its chief scenario editor. Referencing a story published in Louella’s hometown Illinois newspaper the Dixon Telegraph in 1936, Parsons biographer Samantha Barbas writes that, although Parsons’s application for the position was initially discarded, she ingratiated herself with Essanay cofounder George Spoor’s wife, who subsequently persuaded Spoor to hire her. Barbas’s account of Louella’s hire differs slightly from that of Louella herself, put forward in her best-selling 1944 book, The Gay Illiterate. Barbas writes that Louella, upon discovering that her cousin Margaret Oettinger was friendly with Ruth Helms, the daughter of George Spoor’s wife’s closest acquaintance, begged the little girl to introduce her to Mrs. Spoor in exchange for movie tickets. In contrast, Parsons recalls that Helms was so impressed by a scenario she had written entitled Chains that the twelve-year-old took it upon herself to acquire Louella a job in the film industry: “Ruth hounded poor Mrs. Spoor so unmercifully that she, in turn, hounded her busy husband into giving me the appointment.” Parsons notes that Essanay not only hired her as scenario editor, but purchased the scenario for the sum of twenty-five dollars. Although no longer extant, Parsons reports that Chains was produced in 1912 staring Essanay heartthrob Francis X. Bushman (Barbas 2005, 33; Parsons 1944, 20–21).

Throughout her later career as a gossip columnist, Louella Parsons’s writing was maligned in the press. The title of her memoir The Gay Illiterate was, in fact, an epithet for Louella coined by screenwriter-producer Nunnally Johnson in a scathing 1939 Saturday Evening Post article on her entitled “First Lady of Hollywood” (Barbas 2005, 247). Four years prior, Joel Faith, in an equally devastating exposé printed in the leftist newspaper New Theatre, described Louella as “a poor reporter and a wretched writer,” attributing her success not to the quality of her work, but to her alliance with newspaper baron and paramour of actress Marion Davies—William Randolph Hearst (Faith 1935, 8). Regardless of the allegation’s veracity, it attests to the perceived influence of Louella in Hollywood—what she herself facetiously referred to as “Parsons Power, whereby with a slight flick of the typewriter I was credited with being able to save or ruin [Hollywood careers]” (Parsons 1944, 170).

Parsons’s critics were evidently unaware of her role in the history of the scenario form prior to writing syndicated gossip for Hearst papers. In addition to her significant editorial responsibilities at Essanay Studios from 1912 to 1915, Louella wrote the scenarios for at least four Essanay productions: not only Chains (1912) but Margaret’s Awakening (1912), The Magic Wand (1912), and the Charlie Chaplin film His New Job (1915). Parsons’s daughter, Harriet, made her film debut in Margaret’s Awakening under the pseudonym “Baby Parsons”; in The Magic Wand she acted alongside Francis X. Bushman (Barbas 2005, 35). Louella also wrote the story for The Isle of Forgotten Women (1927), adapted for the screen by Norman Springer and directed by George B. Seitz. In Louella’s first book, How to Write for the Movies (1915), Parsons proffers advice to aspiring “photoplaywrights” culled from her years in the editorial chair at Essanay. Glossy photographs of Hollywood stars—Pearl White, Theda Bara, Charles Ray, etc.—are interspersed throughout the book, accompanied by baroquely descriptive captions. The eyes of actress Clara Kimball Young are described by Parsons as “dark lustrous orbs [that] suggest the light that lies in a woman’s eyes,” while Geraldine Farrar is dubbed “A song bird whose pictorial solos have enriched the shadow stage” (2). How to Write for the Movies confirms Parsons’s significant role in the history of the scenario form as well as presages her fascination with the cult of Hollywood celebrity.

Discussing her childhood literary efforts, Louella Parsons in The Gay Illiterate writes: “A ‘wronged girl’ was usually the subject of my writings, and I was always violently on the side of ‘the Woman’ in the case. This prejudice in favor of my own sex has followed me along my entire career” (11). Indeed, Parsons’s career attests to a commitment to the rights of women in both the field of newspaper journalism and the motion picture industry. As Barbas notes, while employed at the Chicago Herald, where she wrote her first regular motion picture column, “Seen on the Screen,” Louella was handed a “sob sister” assignment. That is, she was asked to write on the eight hundred deaths that resulted from the capsizing of a Lake Michigan ferry using maudlin, characteristically “feminine” prose. Barbas explains that sob sister writing, although criticized as sensationalistic, made the careers of the best of the early twentieth century female journalists (56). After leaving the Herald for the New York Morning Telegraph in 1918, where she wrote the column “In and Out of Focus,” Parsons became involved with women’s organizations such as the Woman Pays Club, whose members included early screenwriters Anita Loos and Frances Marion; the Professional Women’s League; and the New York Newspaper Women’s Club (Barbas 2005, 69) In 1926, Louella shocked her male journalist colleagues when she joined them in the press box at the Dempsey-Turner boxing match in Philadelphia, on which she reported for Hearst’s the Los Angeles Examiner (Barbas 2005, 115). Parsons had joined the paper that same year to begin her column “Flickerings in Filmland.” In 1928, Louella and her daughter Harriet established the Hollywood Women’s Press Club, an informal forum for female reporters and fan magazine writers to exchange ideas and gossip over lunch at the Brown Derby (Barbas 2005, 124–5).

Like Louella, Harriet Parsons was a shrewd professional who combated the prejudices of her contemporaries in order to achieve success in the Hollywood film industry. Upon signing with Columbia Pictures to direct and produce the series Screen Snapshots in 1934, Harriet became the only woman producer and, with the exception of Dorothy Arzner, the only woman director working in Hollywood at that time (Barbas 2005, 166).

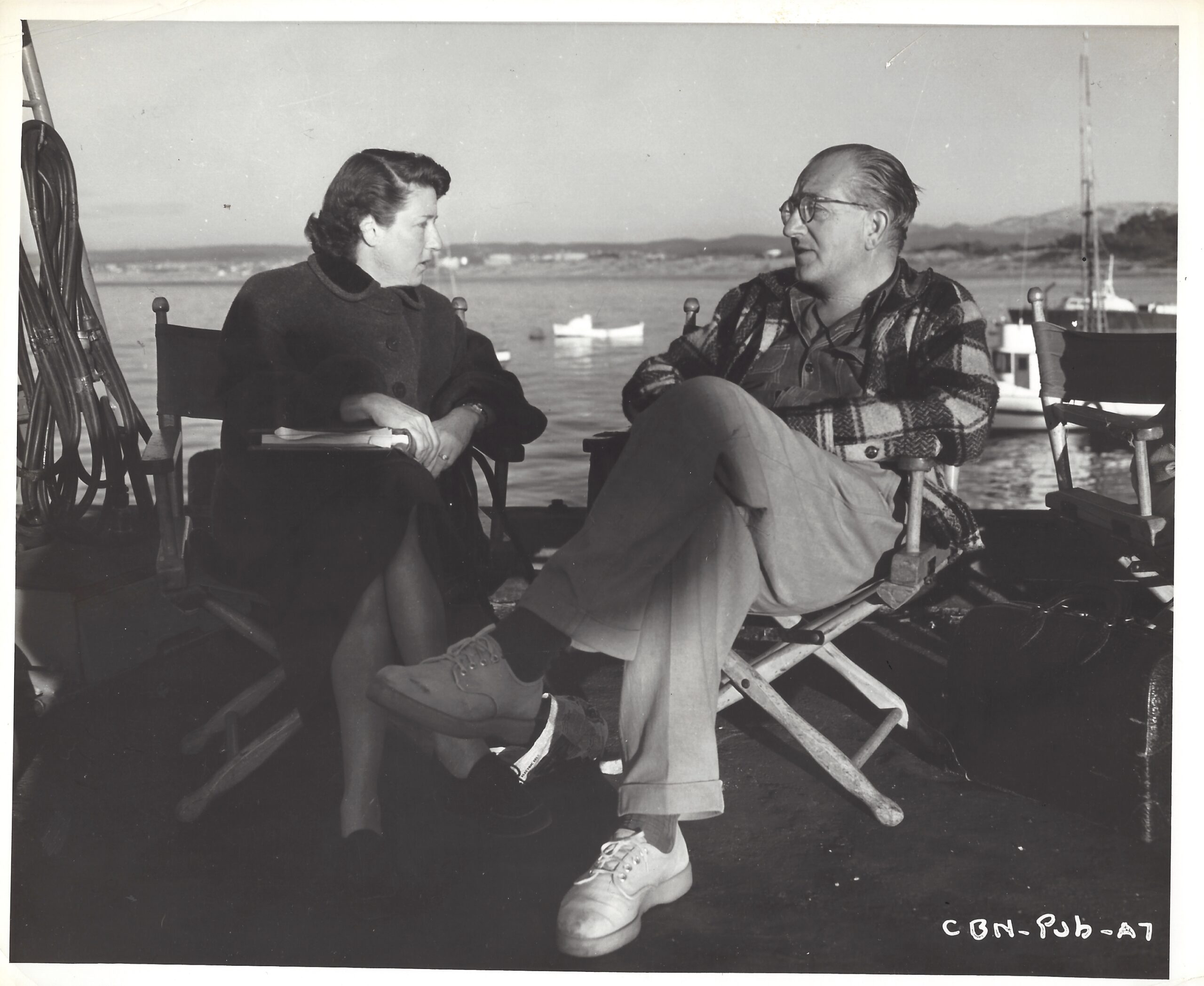

Although RKO initially denied her the opportunity to produce a film version of Arthur Wing Pinero’s play “The Enchanted Cottage,” she alleged because she was a woman, Harriet went on to produce several classic films for the studio (Crane 1982, 30, 35). And as film historian Arthur J. Mann notes, not only did Harriet exceed the circumscribed roles assigned to women within the studio structure—she was also one of a small coterie of lesbians to exert creative control behind the camera (Mann 2001, xvi). Although Harriet was indebted to her mother for helping to launch her career, according to columnist Tricia Crane, the iconic Louella cast a formidable shadow over her diminutive daughter. Following Harriet’s graduation from Wellesley College in 1928, Louella arranged for Harriet to begin work as a junior writer at MGM. Because Hearst was aligned with MGM in the 1920s, Louella knew she could appeal to the studio for the favor (Barbas 2005, 171; Pizzitola 2002, 217). “You couldn’t be any more junior than I was,” acknowledged Harriet in an interview with Crane shortly before her death. “I realized they had hired me because of my mother, and I quit to move to New York” (qtd. in Crane 1982, 30). In New York, Harriet achieved success as a writer for motion picture fan magazines and was appointed assistant editor of Photoplay. However, a severe bout of pneumonia forced Harriet to move back to Hollywood and to Louella, who acquired her a position at Columbia. There she produced Screen Snapshots, featuring “the stars at work and play,” until 1941, at which time Harriet left Columbia for Republic Pictures, tempted by the false promise of the opportunity to produce her own feature. She would not realize this goal until departing Republic for RKO, where she produced such films as The Enchanted Cottage (1945), I Remember Mama (1948), and Fritz Lang’s Clash by Night (1952). Although she achieved her greatest success after the coming of sound, beginning with her roles at Essanay, the foundation of Harriet Parsons’s career was established in the silent era.

See also: Gladys Hall