This particular pioneer had a transcontinental career. As a result, her profile will include multiple essays by different authors.

Her American Career

By Robert Sitton

Iris went to America, taking along her husband of seven years, Alan Porter, the poet and literary editor of The Spectator. Arriving at the start of the Depression, they were little known in New York and their first five years were difficult. Barry ghost-wrote a book on Afghanistan and, with Porter, who was also trained as a psychologist, a directory of dreams. She published book reviews in the New York Herald-Tribune, but the two lived precariously on freelance fees and Porter’s income as a therapist and professor at the New School.

Iris’ prospects brightened in 1932 when she became a regular guest at the Askew salon, a remarkable assemblage of modernists who met on Sunday evenings at the home of Kirk Askew, the American representative of Durlacher Brothers art dealership, and his socialite wife, Constance. There, Iris became friends with Philip Johnson, the architect, composers Paul Bowles and Virgil Thomson, architecture historian Henry Russell Hitchcock, theater director John Houseman, art historians Agnes Rindge and Margaret Scolari Barr, dance impresario Lincoln Kirstein, A.E. “Chick” Austin, the adventurous director of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, and, most fatefully for Iris, Alfred Barr, Jr., director of the newly established Museum of Modern Art.

Iris and Porter divorced in July 1934 and within a month Iris married John “Dick” Abbott, a stockbroker six years her junior who liked motion pictures more than his job on Wall Street. Abbott, a somewhat dour numbers man, accompanied Iris to the Askew salon, but few remembered his being there. Barr, however, decided that Abbott and Barry should together write a proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation for funding a film library at the Museum. During the fall and winter of 1934-35 Iris and Abbott polled colleges and universities, assessing their interest in films for study. Positive responses included in the couple’s proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation resulted in the founding in 1935 of the Film Library of the Museum of Modern Art, supported by a grant of $100,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation and most of an additional $60,000 from John Hay “Jock” Whitney, who had introduced Technicolor to Hollywood. John Abbott was named the library’s first director and Iris Barry was named curator.

Campaigning to secure films for the library, Barry and Abbott went to Hollywood. On August 1, 1935, they appeared before a glittering crowd at the Pickfair mansion of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. Many in attendance were in control of major film collections, among them Pickford herself, Charlie Chaplin, Walt Disney, Walter Wanger, and Samuel Goldwyn. Barry and Abbott appealed to their desire for immortality, arguing that by donating their films for preservation they would live in popular memory. Their appeal was successful. Films were forthcoming and began to circulate in 1936.

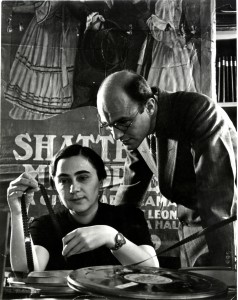

Pickfair guests (left to right): Frances Goldwyn, John Abbott, Samuel Goldwyn, Mary Pickford, Jesse Lasky, Harold Lloyd, Iris Barry in 1935. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

In May 1936 the couple traveled to Europe where many nascent film archives had been established as political instruments in a time of impending war. Iris undertook the trip with a dual purpose. In addition to seeking films of aesthetic significance she secured the approval of Secretary of State Cordell Hull to bring back films that, as she put it, “might become politically or militarily useful to the United States in the event of our entry into conflict” (Sitton 213). This ambition reversed her earlier tendency to avoid politics. Visits to London, Paris, Hanover, Berlin, Warsaw, Moscow, Leningrad, and Stockholm brought in films now regarded as iconic, including the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Murnau, Pabst, and Wiene, and the most controversial of which was Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935).

Although the Museum of Modern Art is known as a venue for film exhibition, exhibiting films was not an early priority of the Film Library. The first attempts in 1936 met with a mixed reception when many in the audience derided the antiquated styles of early cinema. More successful was an initiative in September 1937 to create a new kind of film course, one in which the audience interacted with filmmakers after their films were screened. The course was co-sponsored by Columbia University and the Museum of Modern Art and among those attending were many who would shape film education in the future, including the film critic Arthur Knight whose influential Thursday night classes at the University of Southern California were, in his words, “patterned precisely after those long-ago Tuesdays with Iris Barry” (1978, 19).

The approach of war brought pressures upon the Film Library. In the spring of 1939, Nelson Rockefeller became President of the MoMA board and that summer turned the administrative reins of the Museum over to Dick Abbott. In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Rockefeller Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, a role he carried out in cooperation with the Office of Strategic Services, a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. Through Rockefeller, Iris and the Film Library facilitated the production of many films favorable to U.S. policy in Latin America, including films produced by Walt Disney featuring his cartoon characters. She also screened German propaganda films for American filmmakers aiding the Allied cause. In response, Frank Capra, William Wyler, John Huston, and others produced the Why We Fight series, a major wartime recruitment tool.

After the war ended, Barry found herself faced with a generation of filmmakers using lightweight 16-millimeter film equipment to produce a decidedly personal art. Iris’ stated preference for narrative consistency in film left her unprepared for the non-narrative character of many post-war independent films. In late 1945, as arbiter of a grant application to the Rockefeller Foundation by the filmmaker Maya Deren, Barry rejected Deren’s proposal outright and concurred with a letter from the Foundation’s John Marshall that Deren would be wise to adopt another profession. In response, in February 1946, Deren rented the Provincetown Playhouse in New York’s Greenwich Village for a retrospective of her “abandoned” films. In the audience were Amos and Marcia Vogel who went on to found the highly influential film society, Cinema Sixteen. Others present formed the New American Cinema Group, followed later by the Filmmakers Cooperative, Canyon Cinema Cooperative, and countless other independent film groups. With the establishment of these organizations, American film culture became more complex and decentralized, challenging the leadership of the Film Library.

In February of 1949 Iris suffered a health crisis. She underwent treatment for cancer, which, although ostensibly successful, left her insecure about her mortality. At the same time, the French Ambassador to the U.S. notified her of her induction into the French Legion of Honor. Iris had helped Henri Langlois, director of the Cinémathèque française shelter many valuable films from the Germans during wartime, and the French were grateful. They also recognized her as the principal founder of FIAF (the International Federation of Film Archives, founded in 1938), for which Iris served as Life President. In the late 1940s Iris was increasingly asked to do what she did not care to do: raise money. Film activity at MoMA for too long had depended on Rockefeller support and the costs of film preservation were outstripping income. After her cancer operation she received a $4,000 gift from Nelson Rockefeller to support her recovery. She took the money and sailed for France. Iris had served on the jury of the first Cannes Film Festival in 1946. There, she met a Frenchman, Pierre Kerroux, a rough, handsome Breton twenty years her junior. Iris joined him again in the south of France in 1949 while on convalescent leave from the Museum. She quietly decided to remain there. With Rockefeller’s check she bought a car and a tumbledown farmhouse in Fayence, the village noted for its pottery.

For fifteen years this couple co-existed warily, selling antiques from the first floor of a townhouse lent to them by Chick Austin. Occasionally, Iris made trips for FIAF to foreign archives. In 1955 NBC asked her to consult on their Victory at Sea World War II series, although privately she despised television. In 1962 she returned to New York briefly as the honoree of the first New York Film Festival. Spurred on by deteriorating relations with Kerroux, she tried reconciling that year with her two children by Wyndham Lewis in England, but to no avail. Alone and ill with cancer of the throat (she had been a lifelong smoker), Iris entered the hospital in Marseilles where an operation in October 1969 left her unable to speak. She died there on December 22, 1969, and is buried in the cemetery above Fayence. Her grave bears no mention of her accomplishments.