Cleo de Verberena was the first woman to recognize herself and to be recognized as a film director in Brazil. She was the protagonist and the director of the silent feature film O Mistério do Dominó Preto/The Mystery of the Black Domino (1931), based on the story of the same name by Aristides Rabello. Born Jacyra Martins da Silveira in Amparo, a small city in the state of São Paulo, she moved to the capital after the death of her father to be with some of her eight siblings who already lived there.

Life in the capital was different than in Amparo, and São Paulo of the 1920s was changing and expanding dramatically. It was the home of the great coffee barons and a rising elite class that benefitted from industrialization, as well as a place of immigrants, especially Italians, and former slaves and their descendants. The center of São Paulo was already full of movie theaters, stores selling musical instruments, bookstores, theaters, haute couture studios, and confectioneries. Planned neighborhoods were built for the wealthy population, automobiles shared the streets with electric trams, and the streets were no longer as dangerous with the full installation of electricity in 1930 (Schpun 1997). Going to the cinema was a common practice for the modern women of São Paulo and Jacyra loved to watch films and think about the person behind the camera. According to an unpublished interview, given by her son, Cesar Augusto Melani, to the journalist José Maria do Prado, she was interested in the “brain” that put everything in order–the individual who oversaw the technicians and crew and made history come alive on the screen (Prado 1981, n.p.).

It was in the city of São Paulo that Jacyra met Cesar Melani, with whom she married and had a single child, around 1925. Melani was born in Franca, a small town in the state of São Paulo on May 28, 1903 and went to the capital to study medicine. When they got married, however, Cesar had already given up on that ambition and was trying to make it, unsuccessfully, as a businessman. According to their son in the aforementioned unpublished interview, the couple shared a common passion for the cinema (Prado n.p.).

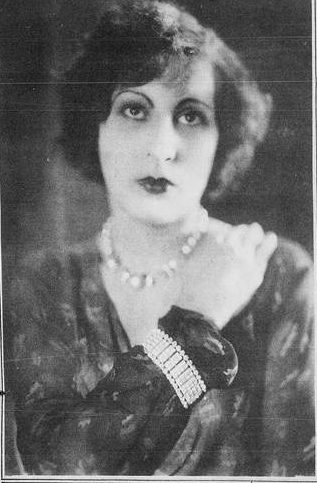

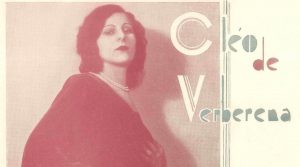

1930 Cinearte headline: “The first Brazilian woman filmmaker.” Courtesy of the Biblioteca Digital das Artes do Espetáculo.

Cesar was from an important family in Franca and after the death of a relative, he inherited a great amount of money. The couple decided to use this inheritance to start making films. Cesar hoped to become a great businessman and Jacyra desired to be a great filmmaker. Together, they opened EPICA-FILM, a production company that had an office in a building in Praça da Sé, one of the most prestigious neighborhoods at the time. They also rented a house in the upscale neighborhood of Santa Cecilia, where they built a small studio in the back and allocated equipment imported from France for the enterprise. In 1930, the couple started the production of O Mistério do Dominó Preto. Thinking about the sound of their names and the names of Hollywood stars, Jacyra adopted the pseudonym of Cleo de Verberena and Cesar became Laes Mac Reni.

There was a lot of publicity during the production of the film, especially in the magazine Cinearte, which was trying to strengthen Brazilian cinema through the consolidation of a star system similar to that of the United States. Between 1930 and 1931, many images of Verberena and stills from the film were published in Cinearte. For example, in May 1930, an article celebrated the pioneering work of Cleo de Verberena as the first Brazilian woman filmmaker (Rosa 1930, 6).

In addition to her role as director, Verberena also played a major role in the now lost O Mistério do Dominó Preto. It is likely that only one copy was made and did not survive the passage of time. Fortunately for contemporary scholars, shortly before its release, a considerable synopsis, as well as images from the film, was published in Cinearte (“O Mistério do Dominó Preto” 8-9, 40-41). The story centers on the murder of a married woman named Cleo, played by Verberena, who is dressed in a black Domino costume during the carnival in São Paulo. This famous character, coming from the tradition of Commedia dell’arte, allowed anyone complete anonymity since it was composed of a long tunic that covered the whole body, as well as a mask and gloves. O Mistério do Dominó Preto makes this anonymity part of the plot. On her way to see her lover, Cleo is poisoned by someone pretending to be him, who is also dressed as a Domino. Although killed early, Cleo appears very alive throughout the film through the use of flashbacks, which set up her relationships with various characters in the story, while an ex-lover leads the investigation into her murder.

Cinearte image of Cleo, dressed in the black Domino costume, going to see her lover in O Mistério do Dominó Preto (1931). Courtesy of the Biblioteca Digital das Artes do Espetáculo.

Rabello released three different versions of the film’s source material in magazines and a newspaper between 1912 and 1926. Today, we have access to all three and can compare them to the published film synopsis. Verberena considerably modified the narrative, making it less conservative and moralistic. In the film, after being poisoned while drinking juice with the man she thinks is her lover, Cleo is rescued in the street by an ex-lover, a medical student who takes her home to try to reverse the effects of the poison. In Rabello’s versions, the medical student is not an ex-lover, but rather just someone she knew. Additionally, in Verberena’s film, before running into her killer, Cleo tells her husband that she is going out to enjoy the carnival. In Rabello’s versions, the main character, who does not have a name, secretly goes to the carnival to see her lover. Ultimately, Verberena makes the female character more daring and independent, gives her multiple lovers, and has her go to the carnival alone, without having to lie to her husband about her activities. Verberena also changed the ending of the story. In her version, the murderer is a man and the character of Cleo is properly buried. On the other hand, in Rabello’s versions, the murderer was another woman, the jealous girlfriend of the lover that Cleo was going to meet. Additionally, the victim does not meet the same end in the source material; the police are unaware of the crime, and the body of the “unworthy” woman dressed as the black Domino is quartered, packed, and dumped into a wasteland by the lover, the medical student, and his friend in the first version and, in the other two versions, the body is thrown into the sea.

Cleo de Verberena and Carmen Santos in Cinearte in 1932. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Digital das Artes do Espetáculo.

O Mistério do Dominó Preto debuted in São Paulo on February 9, 1931. It was shown in five theaters in the capital and one in the city of Curitiba, according to the Cinemateca Brasileira’s entry on the film online (“O Mistério do Dominó Preto” n.p.). In order to increase the couple’s income and to cover the expenses of the film, Cleo acted in two theatrical pieces directed by Luiz de Barros in 1931. In the same year, it was announced by the newspaper A Gazeta that she would play the main role in the film Canção do Destino, by Plínio Ferraz (“Cinemas” 6). Unfortunately, this production was never realized. In 1932, the family left for Rio de Janeiro with the intention of having O Mistério do Dominó Preto screened there. They visited the Cinédia studios, the first Brazilian attempt at film industrialization, and Cleo met the producer, actress, and future director Carmen Santos and other big names in Brazilian cinema. However, there is no evidence that the film was shown in Rio de Janeiro.

Like other Brazilian productions of the period, O Mistério do Dominó Preto was more of a financial loss than a profit. The distribution of national films was difficult since exhibitors often gave preference to the titles that generated profit, such as American films. In the aforementioned interview, Cesar Augusto told Prado that in this period his father was suffering from nervousness because he had put his entire inheritance into the production of O Mistério do Dominó Preto. He said that his mother sold everything she had to try to cover the expenses of the film, but the gap was too big (Prado n.p). In 1935, on his son’s birthday, Melani was found dead in an armchair in his living room. He was only thirty-one years old.

Her premature widowhood and her financial loss were probably what forced Verberena to abandon the cinema. In the 1940s, she remarried a Chilean diplomat, Francisco Landestoy Saint-Jean, with whom she would live in Rio de Janeiro, England, and Chile. Her daughter-in-law, Judith Haltenhoff Meza, said that Cleo did not talk about her past in film (2017 n.p.). Verberena died at the age of sixty-eight in the city of São Paulo. Her history has never been told and in Brazilian cinema books, when mentioned, only a few lines are reserved for her. Yet, at a time when women did not have the right to make decisions for themselves—the Brazilian Civil Code of 1916, then in force, dictated that they should be treated as minors dependent upon a father or husband—Cleo de Verberena, or Jacyra Martins da Silveira, directed her own film, led a team composed mostly of men, and presented Brazilian audiences with a modern story and female character.

See also: Carmen Santos