by

Victoria Sturtevant

Bess Meredyth is mentioned in nearly every account of women screenwriters of the silent era, but very few details about her work seem to make it into print. The richest source for information about this extremely prominent screenwriter is Eighty Odd Years in Hollywood, the autobiography of Meredyth’s son, John Meredyth Lucas. This text, too, however, leaves large gaps in detail and in the chronology of the author’s mother’s career, and the son reflects: “It, unfortunately, never seemed important that I learn Mother’s early history. She never wrote it, only mentioned a few disconnected anecdotes. I never asked. By the time the questions were formed, the answers had died” (19).

Bess Meredyth. Private Collection.

Born Helen MacGlashan in Buffalo, New York, Bess Meredyth’s father was the manager of a local theatre, and she began working as an organist and later a vaudeville light comedienne in her teens. She came to Hollywood in 1911, working as an extra for the Biograph Company for a short while, and quickly began writing scenarios on a freelance basis to supplement her income. While at Biograph, Bess Meredyth met and married actor and director Wilfred Lucas, who became her frequent collaborator. In 1914, the couple left Biograph to run their own unit at the Universal Manufacturing Company, where she became a fairly well-known comic actress, appearing primarily in “Willy Walrus” and “Bess the Detectress” shorts. The period from 1914 to 1920 seems to be Meredyth’s most prolific, a period during which she wrote, acted, and directed motion pictures with her husband. A 1927 Moving Picture World profile by Tom Waller claims that Meredyth wrote roughly two hundred original stories while she was at Universal, then quit acting to devote herself to writing full time, producing a story per week for Kalem serial star Ruth Roland. Waller further notes that Meredyth then returned to Universal to cosupervise the Yonkers, New York, Triangle Film Corporation Studio, and codirected some motion pictures with Allan Dwan (15). Published sources assign her only one feature directing credit, as codirector of the 1918 Bluebird release Morgan’s Raiders. The American Film Institute catalog also notes, however, that copyright records for the National Film Corporation feature release The Girl from Nowhere (1919) indicate that it was “Written and Directed by Bess Meredyth and Wilfred Lucas,” although the press book credits only Lucas (324). Because they collaborated so closely, “credit” is ambiguous and inconsistent, especially in their early work, as was the case with so many other married couples who collaborated as writers throughout the silent and into the early sound era. Yet the differences between these collaborations is also significant, and Meredyth and Lucas were perhaps more like Agnes Christine Johnston and Frank Mitchell Davey than Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman, the difference being that Lucas, like Davey, in addition to writing screenplays also worked as a director.

In 1920, Meredyth and Lucas sailed to Australia to make action films with stuntman and star Reg “Snowy” Baker. Although they only stayed in Australia for a year, the experience with a small crew far from Hollywood gave Meredyth the chance to take a more active role in motion picture production, including the cutting and titling of her films (Waller 15). This episode also suggests that Meredyth was very much at home with the masculine ethos of action filmmaking, and was willing to travel halfway around the world to pursue her work, infant son in tow.

Bess Meredyth. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

When the family returned to Hollywood in 1921, Bess Meredyth resumed a career during which she was ultimately to accumulate more than one hundred and twenty-five writing credits, working in succession for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Warner Brothers, Goldwyn Productions, First National Pictures, and Columbia Pictures, before landing again at MGM in 1928. Her credits include a remarkable number of milestones and prestige pictures. She was a fast-working studio contract writer and consummate technician who appears to have had a very pragmatic approach to her work. Famously, MGM sent Meredyth to Italy in 1924 to help rescue the production of Ben-Hur that was falling grossly behind schedule and running over budget, and she is listed on the writing credits with Carey Wilson as “continuity,” although she is widely known to have supervised the enormous production.

As in the Ben-Hur episode of her career, Meredyth seems to have been prized particularly for her ability to handle sticky situations in a way that helped the studio run smoothly. Meredyth’s fellow screenwriter Gene Fowler praised her ability to humor the volatile John Barrymore, who would show up at her house with new and often outrageous passions or ideas for his films (1976, 236–237). John Meredyth Lucas also admiringly described his mother’s ability to fend off advances from amorous leading men with a wry retort, a talent that probably served her well in her work with male film stars and in male genres throughout her career (29–30, 36).

Bess Meredyth was equally adept with women’s films, however, and notably adapted a series of delicate vehicles for Greta Garbo, including Michael Arlen’s racy novel The Green Hat, which was produced by MGM as A Woman of Affairs (1928). Meredyth was faced with the more or less impossible task of maintaining narrative coherence while evading Production Code censure of the novel’s original narrative material, which involved venereal disease, alcoholism, infidelity, unwed pregnancy, and suicide. For A Woman of Affairs, a remarkable melodrama that survives from the silent era, Meredyth received a best adapted screenplay nomination at the first Academy Awards ceremony, held in 1929. One of the thirty-six artists (including screenwriter Jeanie Macpherson) who founded the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1928, Meredyth was nominated for two screenplays, Wonder of Women (1929) as well as A Woman of Affairs.

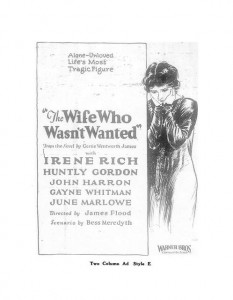

Ad The Wife Who Wasn’t Wanted (1925). Private Collection.

It is perhaps surprising, given such honors, that Bess Meredyth’s career faded quickly in the 1930s—a fact that is partially attributable to changes in the organization at MGM, particularly the death of her friend Irving Thalberg, whose support had also advanced the screenwriting career of Frances Marion in that competitive studio writing department. But the studio upheaval also coincided with a series of illnesses that would render Meredyth bedridden for much of the rest of her life. Lucas describes a series of panic attacks that began to affect his mother while she was still at MGM in the early thirties, and left her under a doctor’s care for much of the rest of her life (62, 72–74). Though she no longer maintained a formal career during these years, it is likely that she continued to exert herself creatively through the films of her third husband, Michael Curtiz, director of Casablanca (1942). Years later, Casablanca screenwriter Julius Epstein would recall her contributions to her husband’s career: “When we had a story conference and Mike came in the next day and made criticisms or suggestions, we knew they were Bess Meredyth’s ideas, not his, so it was easy to trip him up. We’d make a change and say, ‘What do you think, Mike?’ and he’d have to go back and ask Bess” (Harmetz 123).

See also: “Shaping the Craft of Screenwriting: Women Screen Writers in Silent Era Hollywood”

Bibliography

Fowler, Gene. Good Night Sweet Prince. 1943. Cutchogue: Buccaneer Books, 1976.

Fowler, Gene, and Bess Meredyth. The Mighty Barnum, A Screenplay. New York: Garland, 1977.

Harmetz, Aljean. Round Up the Usual Suspects. New York: Hyperion, 1992.

Lucas, John Meredyth. Eighty Odd Years in Hollywood: Memoir of a Career in Film and Television. Jefferson: McFarland, 2004.

Miles, Allie Lowe, and Bess Meredyth. When a Man Loves: The Story of a Deathless Passion. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1927. [Note: This book is based on the motion picture story by Bess Meredyth.]

Waller, Tom. “Bess Meredyth.” The Moving Picture World 2 July 1927: 15.

Filmography

A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles:

1. Bess Meredyth as Screenwriter, Coscreenwriter, Source Author, Adaptation, and Continuity

The Modern Prodigal/One Good Turn Deserves Another. Dir.: D. W. Griffith, sc.: Bess Meredyth, st.: Bess Meredyth, Dell Henderson (Biograph Co. US 1910) cas.: Clara T. Bracey, Kate Bruce, Dell Henderson, si, b&w, 16mm, 992 ft. Archive: Library of Congress, Museum of Modern Art, UCLA Film & Television Archive, George Eastman Museum, BFI National Archive.

Spellbound/The One-Eyed God. Dir.: Harry Harvey, sc.: Bess Meredyth (Balboa Amusement Co. US 1916) cas.: Lois Meredith, William Conklin, si, b&w, 35mm, 5 reels. Archive: Library of Congress.

The Little Orphan. Dir.: Jack Conway, sc.: Bess Meredyth, Elliot J. Clawson (Bluebird Photoplays, Inc. US 1917) cas.: Ella Hall, Margaret Whistler, si, b&w, 35mm, 3 reels of 5. Archive: Library of Congress, Library and Archives Canada.

Scandal. Dir.: Charles Giblyn, sc.: Bess Meredyth, Charles Giblyn (Selznick Pictures Corp. US 1917) cas.: Constance Talmadge, Aimee Dalmores, si, b&w, 5 reels. Archive: Museum of Modern Aart [USM], BFI National Archive.

The Man from Kangaroo. Dir.: Wilfred Lucas, sc.: Bess Meredyth (Carroll-Baker Australian Productions AT 1919) si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

One Clear Call. Dir.: John M. Stahl, sc.: Bess Meredyth (First National Pictures, Inc. Louis B. Mayer Productions US 1922) cas.: Claire Windsor, Milton Sills, si, b&w, 8 reels, 7,450 ft. Archive: George Eastman Museum.

The Song of Life. Dir.: John M. Stahl, st.: Frances Irene Reels, sc.: Bess Meredyth (Louis B. Mayer Productions US 1922) cas.: Gaston Glass, Grace Darmond, Georgia Woodthorpe, si, b&w, 6,910 ft. [orig. 6,920 ft.], 35mm. Archive: Library of Congress.

Thy Name Is Woman. Dir.: Fred Niblo, adp./cont.: Bess Meredyth (Louis B. Mayer Productions US 1924) cas.: Barbara La Marr, Edith Roberts, si, b&w, 9 reels, 9,087 ft. Archive: George Eastman Museum.

Ben Hur. Dir.: Fred Niblo, Ferdinand P. Earle, Charles J. Brabin, William Christy Cabanne, J. J. Cohn, Rex Ingram, story: Lew Wallace, adp.: June Mathis, sc./cont.: Carey Wilson, Bess Meredyth, titles: Katherine Hilliker (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1925) cas.: Ramon Novarro, Francis X. Bushman, May McAvoy, si, b&w/color, 35mm. Archive: Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, Bulgarska Nacionalna Filmoteka, Cineteca del Friuli, Filmoteka Narodowa, George Eastman Museum, BFI National Archive, EYE Filmmuseum, Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, Cinemateca Romana, UCLA Film & Television Archive, Harvard Film Archive, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Lobster Films, Library of Congress, Danske Filminstitut.

Ben-Hur. [Trailer]. Dir.: Fred Niblo (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1925) si, b&w, 35mm & 16mm. Archive: Cineteca del Friuli, Library of Congress, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

The Sea Beast. Dir.: Millard Webb, sc.: Bess Meredyth, Herman Melville, Rupert Hughes, Jack Wagner (Warner Bros. US 1926) cas.: John Barrymore, si, b&w, 35mm, 10 reels, 10,250 ft. Archive: Cineteca del Friuli, George Eastman Museum, Library of Congress, Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, UCLA Film & Television Archive, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lobster Films.

Don Juan. Dir.: Alan Crosland, sc.: Bess Meredyth, Walter Anthony, Lord Byron, Maude Fulton (Warner Bros. US 1926) cas.: John Barrymore, Mary Astor, si/sd, b&w, 35mm, 13 reels. Archive: Fondazione Cineteca Italiana, George Eastman Museum, Library of Congress, UCLA Film & Television Archive, Cineteca del Friuli, Filmoteca Española, BFI National Archive, UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, Harvard Film Archive, Lobster Films.

When a Man Loves. Dir.: Alan Crosland, sc.: Bess Meredyth, Abbé Prévost (Warner Bros. US 1927) cas.: John Barrymore, Dolores Costello, si, b&w, 35mm, 10 reels, 10,049 ft. Archive: George Eastman Museum, Filmoteca Española.

The Scarlet Lady. Dir.: Alan Crosland, st.: Bess Meredyth (Columbia Pictures Corp. US 1928) cas.: Lya De Putti, si/sd, b&w, 35mm, 7 reels, 6,443 ft. Archive: Cineteca Nazionale.

A Woman of Affairs. Dir.: Clarence Brown, sc.: Bess Meredyth, Michael Arlen, Marian Ainslee, Ruth Cummings (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1928) cas.: Greta Garbo, si/sd, b&w, 35mm, 8,319 ft. Archive: George Eastman Museum, Svenska Filminstitutet, Danske Filminstitut, Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, Cinemateca Romana, Münchner Stadtmuseum.

The Yellow Lily. Dir.: Alexander Korda, cont.: Bess Meredyth (First National Pictures, Inc. US 1928) cas.: Billie Dove, Jane Winton, si, b&w, 8 reels, 7,187 ft. Archive: BFI National Archive.

Wonder of Women. Dir.: Clarence Brown, sc.: Bess Meredyth (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1929) cas.: Lewis Stone, Leila Hyams, Peggy Wood, si/sd, b&w [incomplete]. Archive: UCLA Film & Television Archive.

2. Bess Meredyth as Actress

A Sailor’s Heart. Dir.: Wilfred Lucas (Biograph Co. US 1912) cas.: Bess Meredyth, Blanche Sweet, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Museum of Modern Art, Cinémathèque Québécoise.

When Bess Got in Wrong. Sc.: A. E. Christie (Nestor Film Co. US 1914) cas.: Bess Meredyth, Stella Adams, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: Library of Congress.

B. Filmography: Non-Extant Titles:

1. Bess Meredyth as Co-Director and Co-Screenwriter

Morgan's Raiders, 1918; The Girl from Nowhere, 1919 [uncredited].

2. Bess Meredyth as Screenwriter and Adaptation

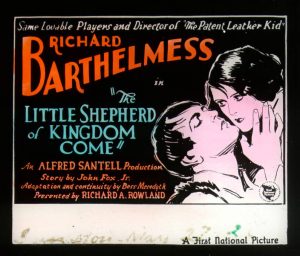

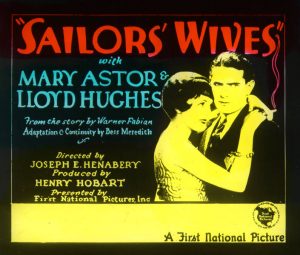

Cross Purposes, 1913; The Gratitude of Wanda, 1913; The Mystery of Yellow Aster Mine, 1913; The Countess Betty's Mine, 1914; Cupid Incognito, 1914; The Forbidden Room, 1914; The Love Victorious, 1914; The Mystery of Wickham Hall, 1914; Passing the Love of Woman, 1914; The Severed Hand, 1914; The Voice of the Viola, 1914; The Way of a Woman, 1914; The Blood of the Children, 1915; The Fascination of the Fleur de Lis, 1915; The Fear Within, 1915; The Ghost Wagon, 1915; The Human Menace, 1915; In His Mind's Eye, 1915; The Mystery Woman, 1915; Putting One Over, 1915; Stronger Than Death, 1915; Their Hour, 1915; Wheels Within Wheels, 1915; A Woman’s Debt, 1915; Borrowed Plumes, 1916; Bringing Home Father, 1916; Cross Purposes, 1916; The Decoy, 1916; The Heart of a Show Girl, 1916; It Sounded Like a Kiss, 1916; Number 16 Martin Street, 1916; Pass the Prunes, 1916; Pretty Baby, 1916; A Price on His Head, 1916; The Twin Triangle, 1916; The Wedding Guest, 1916; The White Turkey, 1916; The Girl Who Lost, 1917; His Wife's Relatives, 1917; The Light of Love, 1917; The Midnight Man, 1917; A Million in Sight, 1917; One Thousand Miles an Hour, 1917; Pay Me/The Vengeance of the West, 1917; Practice What You Preach, 1917; Three Women of France, 1917; The Townsend Divorce Case, 1917; Treat 'Em Rough, 1917; A Five Foot Ruler, 1917; A Wife's Suspicion, 1917; The Grain of Dust/A Grain of Dust, 1918; The Man Who Wouldn't Tell, 1918; Pretty Babies, 1918; The Red, Red Heart/The Heart of the Desert, 1918; Big Little Person, 1919; The Jackeroo of Coolabong, 1920; The Grim Comedian, 1921; The Shadow of Lightning Ridge, 1921; A Marconi Sleuth, 1922; The Woman He Married, 1922; Strangers of the Night, 1923; The Red Lily, 1924; The Love Hour, 1925; The Wife Who Wasn't Wanted, 1925; The Magic Flame, 1927; Rose of the Golden West, 1927; The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come/Kentucky Courage, 1928; The Mysterious Lady, 1928; Sailors' Wives, 1928.

3. Bess Meredyth as Co-Screenwriter

Women and Roses, 1914; Breaking Into Society, 1916; Fame at Last, 1916; From the Rogues, 1916; He Almost Lands an Angel, 1916; He Becomes a Cop, 1916; A Hero by Proxy, 1916; Hired and Fired, 1916; The Mother Instinct, 1916; The Soda Clerk, 1916; A Thousand Dollars a Week, 1916; Why, Uncle! 1917; Morgan's Raiders, 1918; The Romance of Tarzan, 1918; That Devil, Bateese, 1918; Girl From Nowhere, 1919; The Fighting Breed, 1921; Grand Larceny, 1922; Rose o' the Sea, 1922; The Dangerous Age, 1923; A Slave of Fashion, 1925; Irish Hearts, 1927.

4. Bess Meredyth as Actress

Bred in the Bone, 1913; Gold Is Not All, 1913; Bess the Detectress in Tick, Tick, Tick, 1914; Bess the Detectress or The Dog Watch, 1914; Bess the Detectress or The Old Mill at Midnight, 1914; Dangers of the Veldt, 1914; The Desert’s Sting, 1914; Father’s Bride, 1914; Her Twin Brother, 1914; The Little Autogomobile, 1914; Stolen Glory, 1914; Willie Walrus and the Awful Confession, 1914; The Wooing of Bessie Bumpkin, 1914.

D. Streamed Media:

Clips from The Man from Kangaroo (1919) via the National Film and Sound Archive

Credit Report

While The Modern Prodigal, a 1910 D. W. Griffith film is extant, Bess Meredyth is not credited on FIAF and AFI. Victoria Sturtevant claims the film is “based on the novel The Southerner by Bess Meredyth.” Paul Spehr also lists Bess Meredyth as the source author, and Braff lists her as screenwriter. Both Spher and Braff list Henderson as cast only, not as story writer as he is credited by AFI. A Sailor’s Heat (1912) is another extant title, but Bess Meredyth is not credited on FIAF, nor is the film listed in AFI. Spehr lists Bess Meredyth as an extra in this title. The not extant section of “4. Bess Meredyth as Actress” is based on Spehr’s list. Many of these titles do not appear in AFI and the ones that do make no mention of Meredyth.

Research Update

March 2023: A Five Foot Ruler (1917), a two-reel presumably lost film with a story credited to Bess Meredyth in the trade press, has been added to the filmography.

Citation

Sturtevant, Victoria. "Bess Meredyth." In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. <https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-1g0x-gr09>