By operating traveling movie shows, managing nickelodeons and neighborhood theatres, playing musical accompaniments to films, selling tickets, and singing illustrated songs, thousands of pioneering women, long neglected in published histories, made vital contributions to the development of film exhibition throughout the silent film era. How did female exhibitors gain a foothold in the business in the first thirty years of film history, and why were all but the ubiquitous girl at the box office marginalized? Professionalization, at least in the US film industry, was a gendered process that negatively affected women, and eventually created a masculinized industry. Despite their eviction from picture palace management, women would nevertheless continue to work in all areas of theatres and would remain important as small town and rural exhibitors throughout Hollywood history.

When and How Women Became Film Exhibitors

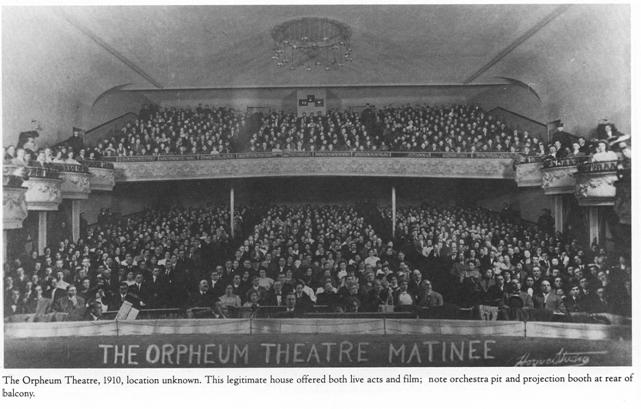

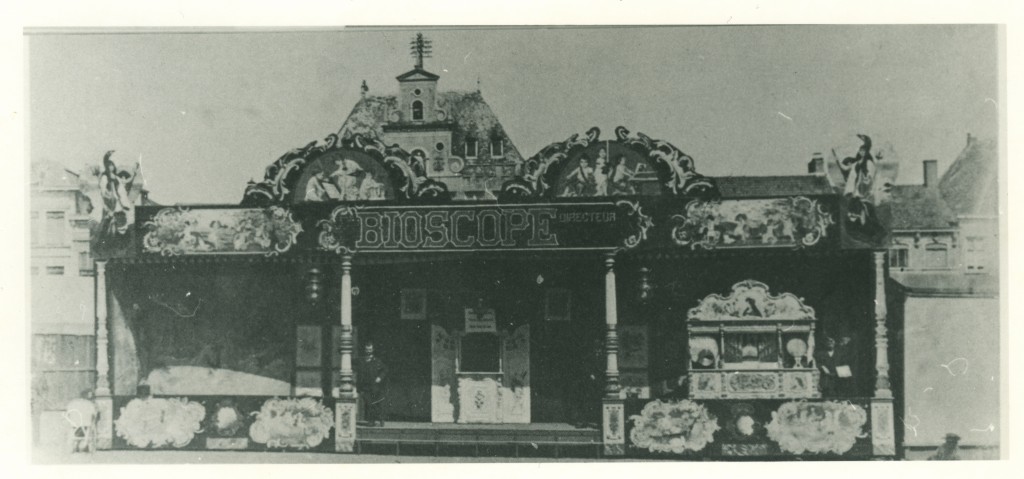

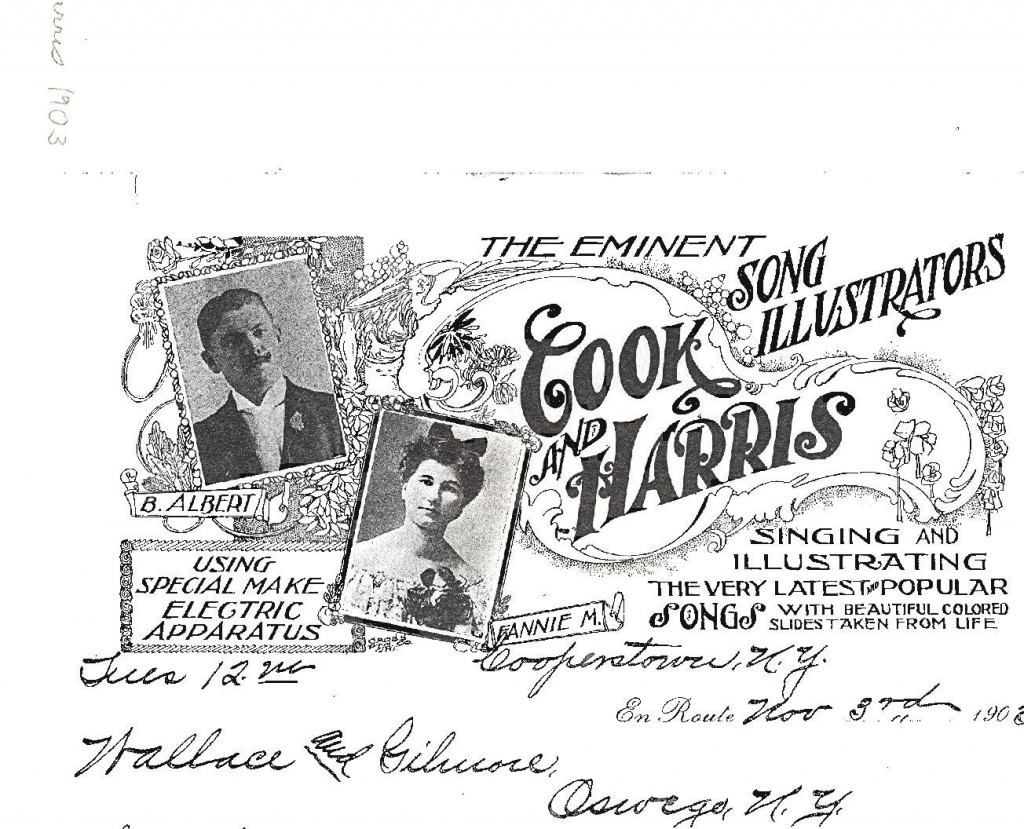

While many of the earliest movie shows were incorporated into urban vaudeville bills, itinerant exhibitors, some of whom were female, took film shows on the road, appearing in small town opera houses and church halls. Fannie Shaw “Harris” Cook and husband Bert Cook played villages in central New York State and northern New England with their Cook and Harris High Class Moving Picture Company from 1903 to 1911; French-born Marie de Kerstrat and her son took a movie show from the 1904 World’s Fair in St Louis to towns across Quebec. Sophie Hancock and Annie Holland were among women who operated Bioscope shows touring English fairgrounds.1Kathryn H. Fuller, At the Picture Show: Small Town Audiences and the Creation of Movie Fan Culture (Washington DC: Smithsonian, 1997; rpt. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001); Serge Duigou and Germain Lacasse, Marie de Kerstrat: L’Aristocrate du cinematographe (Quimer, France: Ressac, 1987); Vanessa Toulmin, “Women Bioscope Proprietors—Before the First World War,” in Celebrating 1895: The Centenary of Cinema, ed. John Fullerton (Sydney, Australia: John Libbey, 1998); Karen Ward Mahar, Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006). There were probably many other women like them, but it was not because film exhibition was an entirely new field and therefore ungendered. The skill required to run a film projector was already masculinized. The Latin-derived names of the first film machines—Kinetoscope, Vitascope, and Kineoptikon—suggest an association with science and technology, traditionally masculine areas of expertise. However, the business of running a small retail, entertainment, or service establishment was not as severely gender-typed. Women had headed troupes of actors and traveling companies from the middle of the nineteenth century, and women business owners can be traced back to colonial times.

Why did women go into film exhibition? Some had a family background in the amusement business, or were already performers; others sought a means to support children or family. A few women were single, but most were either widows with children or associates with spouses, parents, or siblings in a family operation. Fannie Cook was determined to take a full partner’s role, assuring Bert as they discussed starting a moving picture show of their own in fall 1903 (following her recovery from the birth of their child):

I’ll tell you what we will do, Sweetheart, when I get to working. I will pay every cent that is due on the machine, so that it is all paid up by November, and you can lay your money away to put into films, then you and I will take in what fairs we can get and next winter you and I will be in shape to start out for ourselves. Then we will be our own bosses and you can be handling your own door money and we can’t help but make money. Only do as I tell you to, Sweetheart, and you will see that when winter starts in you and I will have something of our own. That’s the only way to make money and you can just be sure that I am the little Girl that is in for making money.2Fannie Cook to Bert Cook, 11 June 1903, Cook papers, file 1903 personal, New York State Historical Association.

Nevertheless, like most working women, Fannie Cook faced many obstacles in entering the new field. Three managers of itinerant movie shows with whom Bert interviewed for projectionist jobs firmly rejected Fannie’s request to work and travel with their companies, arguing that it would be highly improper. Ironically, the most vociferous critic was Mrs. Alonzo Hatch, manager of the Alonzo Hatch Electro Photo Musical Company, who needed assistance while her husband recovered from burns sustained in a projector fire. When Bert rejected her solo offer and insisted that if not hired as a pair, the Cooks would form their own troupe, she responded tauntingly that he could never raise the two thousand dollars the new venture required. “To barn storm it I would advise you never to start.” To flaunt her own success, she ended her reply, “Well I must go to the Opera House. Business has been great.”3Mrs. Alonzo Hatch to Bert Cook, 2 March 1905, Cook papers, file 1905 business, New York State Historical Association. Fannie and Bert Cook thus decided to mount a traveling show of their own.

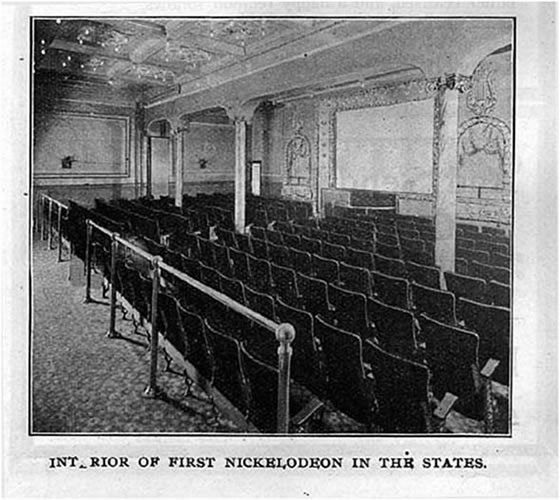

Even as a partnership, the division of labor employed by the Cook and Harris traveling exhibition company reflected traditional gender roles as they were expressed in small business—Bert was the manager of the troupe of four performers and an advance man; he also served as projectionist and occasional soloist. Fannie was musical director, accompanist, ticket seller, and treasurer. A similar gendered division of labor was seen in stationary nickelodeons; while the artists and even business managers were often female, the projectionists were always male.

By the time that Fannie and Bert gave up itinerant shows in 1911 to operate a nickelodeon, Fannie enjoyed considerable company with regard to other female exhibitors. Women appeared in 1907 in the very first pages of the Moving Picture World’s running account of buyers and sellers of nickelodeons. While always a minority, perhaps two to five percent of the total, the names of women in exhibition appeared with regularity over the next several years in published records of theatre property transfers. A sampling of the Moving Picture World from February to December 1909 reveals that there were female exhibitors in urban centers like Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, and Chicago, as well as in smaller towns, like Ardmore, Oklahoma; Connersville, Indiana; Cooperstown, New York; Maitland and Warrensboro, Missouri; Ottawa, Kansas; Paw Paw, Michigan; and the Illinois towns of Abingdon, Kankakee, and Leroy. In 1909, Mrs. F. F. Fuller bought all the moving picture theatres in Hartford City, Indiana.4This conclusion is based on a reading of the Moving Picture World from 1907-1911; examples are taken from Moving Picture World (20 April 1907): 102; (26 June 1909): 875; and (August 1909): 196. A survey of US film trade journals from 1907 to 1918 finds mention of nearly 140 women who were primary purchasers of theatres.5Max Alvarez, unpublished index of women in exhibitor trade journals, 1900-1918. They were a small minority of the approximately 12,000 theatre owners, but were nevertheless discussed in print as colleagues. The six female projectionists noted in the trades, however, were reported as curiosities. Perhaps hundreds more unmentioned women were key to movie theatres as participants in family businesses, partners, or employees holding major responsibilities.

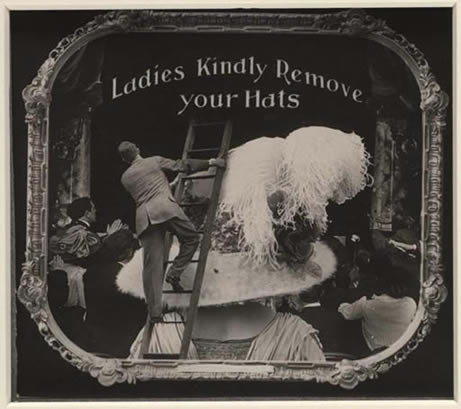

Intriguing for further investigation to enrich our changing view of early cinema is the fact that these women were involved in exhibition during the period when theatre managers exercised great power over the creation of the show. Exhibitors not only selected what films to rent or purchase, but arranged the two-to-fifteen-minute films into programs. “If a piece grows dull at any point,” noted the Moving Picture World in 1907, “the manager can take a pair of shears and cut out a few yards to liven it up.”6“The Nickelodeon,” Moving Picture World, 4 May 1907, 146. They chose the musical accompaniment, sound effects, “illustrated songs,” and other live entertainment. In early days they often interpreted the films for their patrons by providing a lecture to accompany the screening. The movies themselves were only one component of an exhibitor’s production of a sometimes quite elaborate and lengthy multimedia “show.”

What did the presence of female exhibitors mean to the industry? Because much more research needs to be done on exhibition, we do not know enough yet about what male exhibitors thought of their female colleagues. Most available information comes from the pages of movie theatre trade journals that, while aimed at a male-dominated readership, were fully engaged in the female-friendly project of social uplift. Press coverage of exhibitor politics, for example, depicted a high-testosterone, acrimonious milieu in which women exhibitors may well have felt out of place. Exhibitors organized themselves into a trade association at an early date, but getting them to march in the same direction was akin to herding cats. During the campaign to elect a president of the Motion Picture Exhibitor’s League of America in 1913, the challenger to the incumbent was a politically ambitious theatre owner from Fort Worth, Texas. He showed up at the annual convention “in full cowboy regalia, with his six-guns strapped on him,” which he patted menacingly. A New York exhibitor and former prizefighter named Sam Trigger supported his candidacy. But despite superior weaponry, the Texan lost.7Merritt Crawford, “The Organized Exhibitor,” Moving Picture World, 26 March 1927, 313.

While it appears that female exhibitors were notably absent from the highest ranks of internal exhibitor politics, it also appears that the industry’s concerns over outside censorship gave women influence in the business. Women were believed to be morally superior to men, thanks to lingering remnants of the nineteenth-century ideology of “true womanhood.” The mere presence of women could cleanse an audience, a business, or an industry, as it did vaudeville in the 1890s. Impresarios continued to exploit true womanhood after the turn of the century, and we can see evidence of this in the world of film exhibition. The trade journals made enthusiastic note when social reformer Jane Addams installed a movie theatre in the Hull House settlement in 1907.8Moving Picture World, 1 June 1907, 198; Billboard, 3 Aug. 1907, 119. Others female exhibitors facilitated public dialogue about political and racial issues. Amanda Thorpe, a forty-five-year-old widow and film exhibitor from Norwalk, Ohio, came to Richmond, Virginia, seeking virgin territory in which to open movie shows. With the financial backing of local vaudeville impresario Jake Wells, in 1907 she established the Dixie, the city’s first nickelodeon, and then in 1914 the Hippodrome in Richmond’s Jackson Ward, center of the segregated city’s African-American social life. She cooperated closely with the black community, arranging with the black newspaper the Richmond Planet to publish the novelization of the Thanhouser Company serial The Million Dollar Mystery while she played the weekly episodes at her theatre. Thorpe also offered the Hippodrome auditorium as a Sunday meeting hall for civil rights activists.9Motography, 12 October 1912, 304; “That Anti-Segregation Meeting,” Richmond (Va.) Planet, 27 March 1915; Kathryn Fuller-Seeley, Celebrate Richmond Theater (Richmond: Ditz Press, 2001), 24–26. In New Haven, Connecticut, in 1914, African-American exhibitor Anna L. Tucker and her husband, J. H. B. Tucker (publishers of a Black community newspaper, The Plain Dealer), opened the Pacific Theatre for local Black audiences. When the Universal exchange refused to place ads in their paper supporting the film showings, the Tuckers responded with a scathing editorial on their ill treatment, resulting in a flurry of lawsuits and trade journal publicity.10Motion Picture News, 29 August 1914, 64, Alvarez n.p. The Tuckers were not the only African Americans who found a niche in the Black community running theatres. In Chicago, Maria P. Williams was assistant manager of the motion picture theatre for which her husband Jesse L. Williams worked general manager.

The first female exhibitor celebrated by the film exhibitor trade journals was Josephine Clement, profiled by three different trade journals, the Nickelodeon, the Moving Picture World, and Motion Picture News, between 1910 and 1913. The Nickelodeon lauded Clement’s refined management of Boston’s B. F. Keith Bijou Theatre first when it noted her theatre’s “wholesome condition” and “spick and span attendants” in August 1910. Importantly, the Nickelodeon noted that Clement successfully raised the price of admission to twenty cents.11George J. Anderson, “The Case for Motion Pictures,” The Nickelodeon, 15 August 1910, 97. When the Moving Picture World profiled Clement a few months later, the journal attributed her success to the fact that she was a woman: “As we have said before, and as we say again this week elsewhere, the influence of good women in the moving picture field is of incalculable advantage and value.” Clement’s gender allowed her to “aestheticalize [sic] the moving picture house,” and distinguished her from “ignorant, obstinate commercialism of a short-sighted, money-grabbing” exhibitor, the type who “unfortunately rul[ed] the roost.”12“Mrs. Clement and Her Work,” Moving Picture World, 15 October 1910, 859. Becoming perhaps the most renowned exhibitor of her era, and publishing a book Standardizing the Picture Theater, Clement once again became the object of praise in 1913, when Motion Picture News gushed over her refined employees. Even the cashier is

not the giggling, gum-chewing kind;… the man at the ticket receiving box is most gentlemanly; the woman in charge of the coat room is a lady who might well grace a drawing-room; the ushers, all women, are courteous and thoughtful, and the show itself is beyond criticism. There is no comedian, with his disgusting and stale bowery jokes; the illustrated song is not twanged out to a rag-time tune… And as to the pictures themselves, not one is presented that has not some strong lesson to teach.13“The Current Problem and Opportunity of the Moving Picture Show,” Motion Picture News, 11 January 1913, 20, qtd. in Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915. (Berkeley: University of California, 1994), 123.

For their part, female exhibitors really did appear to be interested in cleansing the movies. In 1911, when the Moving Picture World related the surprising story that a film exhibitor filled the empty pulpit of a vacationing Baptist minister, it was, of course, a woman who did so. Miss Ida Mayor, an elocutionist and lecturer as well as a film exhibitor, claimed that her sermon-like shows were “carefully planned to elevate the spectators.”14“Observations by Our Man About Town,” Moving Picture World, 2 September 1911, 615. When several women in Los Angeles banded together in 1912 to buy an $80,000 theatre, it was to show “only pictures with real educational or artistic value.”15“Los Angeles News,” Moving Picture World, 18 May 1912, 641.

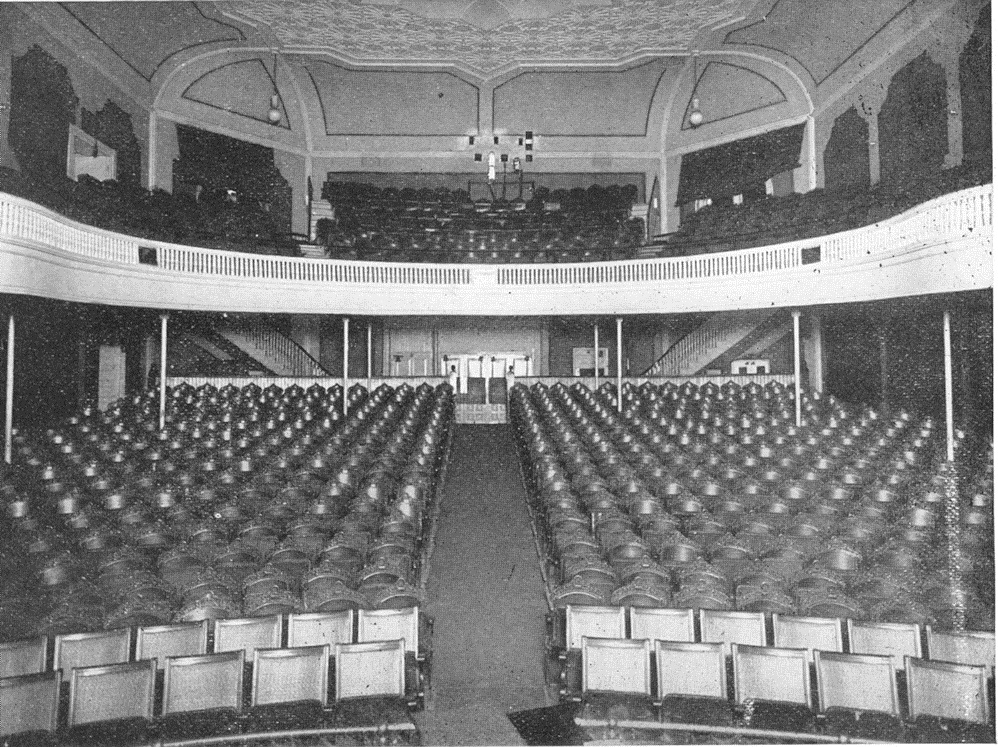

Female theatre owners could not exist in a neutral space since observers successfully played on the belief that women naturally uplifted the industry. But ironically, both male and female exhibitors also employed women for their ability to allure. The most famous example was the ubiquitous “girl in the box office.” It was considered good business to employ a pretty girl to sit in the ticket booth out in front of the theatre and attempt to attract passersby. Manuals for new exhibitors on how to run a theatre instructed them to carefully select a cashier as “the girl’s appearance and dress, her voice and her speech, her glance and her manner” are all noticed by patrons. “The impression she makes is lasting” wrote another, suggesting that a lovely box office attendant attracted like vibrant posters and shining marquee lights and distracted moviegoers from shabby theatre furnishings.16Harold Franklin, Motion Picture Theater Management (New York: George H. Doran Co., 1927), 70, https://archive.org/details/motionpicturethe00haro/page/n7; Frank Ricketson, Management of Motion Picture Theaters (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1938), 137, qtd. in “The ‘Theater Man’ and ‘The Girl in the Box Office,” in Exhibition: The Film Reader, ed. Ina Rae Hark (New York: Routledge, 2001), 148. The use of female employees to accomplish the contradictory goals of uplift and titillation increased as the theatres increased in size. Interestingly, female exhibitors seemed more likely to employ women. Clement was one of the first to use girl ushers, a common gimmick by the mid-1910s, and in 1918, Sara Maxon, the female manager of the 900-seat Ascher Brothers Theatre in Chicago, employed a seven-piece all-girl orchestra.17“Ascher Brothers, Chicago, First in Their City to Have ‘The Female of the Species’ for Theater Manager,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 28 September 1918, 143.

When its doors opened in Los Angeles in 1912, the 900-seat Mozart Theatre incorporated some of the hallmarks of women’s film exhibition—attractive décor, cleanliness, enlightening programming and an all-female staff—including a policewoman, photoplayer operator, and Nellie Lee, the only female projectionist in town. A daring innovator, Mrs. Anna Mozart, the Mozart’s owner and manager, was considered by some to have been the first to show five- and six-reel motion pictures on a regular basis. When they married in 1898, Anna and her husband Edward Kuttner purchased a “French cinematograph” with the intention of exhibiting films in Washington State. Seasoned vaudevillians, the Kuttners owned and managed theatres in Elmira, New York, and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, presenting live performance as well as motion pictures.18Bowser 46-47; Jan Olsson, Los Angeles Before Hollywood: Journalism and American Film Culture, 1905 to 1915 (Stockholm: National Library of Sweden, 2008), 132-152. Evoking nineteenth century lantern culture’s successful formula of education and entertainment while anticipating the art house cinema of future decades, the Mozart Theatre’s high-quality features, vivid travelogues, and Gaumont newsreels provided programs of exceptional interest and variety. It was considered highly unusual for a motion picture establishment to attract “automobile patronage” to the unlikely location of Grand Avenue and 7th Street, and for an audience to “break out into plaudits” for projected screen entertainment, but for several years Mrs. Anna Mozart attracted an appreciative, well-heeled audience of international luminaries, temporarily transforming a lackluster corner of downtown Los Angeles into a micro-cosmopolis.19“Premiere of Peck of Pickles,” Los Angeles Times, 7 August 1912, II5; “Labor Day at the Belasco,” Los Angeles Times, 3 September 1912, II5. See also “Success Hers in Woman’s New Field,” Los Angeles Times, 2 August 1913, III1; “Mrs. Kuttner, Veteran of Theater, Dies,” Los Angeles Times, 27 May 1952, 28.

How Did Male Exhibitors View Their Female Colleagues?

We can start answering this question by considering what the trade journals themselves identified as the best practices of theatre exhibition in the silent era. A model theatre was 1) physically well-maintained, 2) drew an orderly audience, preferably the family trade, and 3) enjoyed consistently high attendance. Female exhibitors drew positive attention because their theatres scored high on all three qualities. In a few cases, women claimed that their sex was particularly well suited to film exhibition. When a journalist praised the female manager of the Lafayette Theatre in Washington DC for keeping her theatre especially clean, comfortable, and well-ventilated, she replied that “it is attention of this nature that is a strong point in a woman’s management of a picture house.”20Motion Picture News, 19 December 1914, 37. Furthermore, families would naturally want to attend a nice, clean theatre. Women were assumed to come by these traits naturally, but male exhibitors could imitate them.

In 1925, when the manager of the large and impressive Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York, was asked what it took to run a picture palace, he cited qualities that could be defined as traditionally feminine: “The house manager of a big theatre is a combination of housekeeper, butler, host, and guardian of the property. His first duty is to see that his guests are happy and comfortable.”21John O’Neill, “The Patron is Right,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 26 December 1925, 33. But part of this role implied crowd control. One exhibitor objected vigorously to female ushers on this point in particular, arguing that if a fight broke out, the women would be screaming and climbing over the seats.22Monte W. Sohn, “Baker on Women,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 1 October 1921, 123. But more often women were admired for their allegedly innate ability to control the behavior of children, including rowdy adolescents. In 1924, exhibitor Janet Noon claimed she got off to a good start at her Schenectady theatre by making it known from the beginning that she would brook no “cutting up” by boys.23“Janet Noon Makes Her Theatre Pay in Dimes,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 17 May 1924, 12. Ellen Mohrbacher, a young widow and mother of three who bought a small-town Oklahoma theatre in 1921, also put her foot down on the first day on the job. When a group of rowdy boys persisted in throwing popcorn and nuts, she turned the lights on, stood in front of them, and said, “I’m going to tell you just like it is… I want you to come in here and enjoy the show and be ladies and gentlemen so your fathers and mothers can enjoy the show, too… I’ve never been used to all this noise and I won’t have it, that’s all.” For the next thirty-five years she enforced her code of conduct by making “purposeful” trips down the aisle with her flashlight.24Doris Henson Pieroth, “The Only Show in Town: Ellen Whitmore Mohrbacher’s Savoy Theatre,” The Chronicles of Oklahoma 60 (3): 268. Twenty-year-old Nettie Hutchinson, who inherited the Idle Hour in Leon, Iowa, in 1920, rued that it had “become sort of a clubroom for the Younger Masculine Set,” but soon she drew a thriving family trade.25“Mere Girl Takes Man’s Job and Makes Idle Hour Most Attractive Theater,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 10 April 1920, 2144.

Good attendance stemmed not only from an orderly audience but also from good showmanship. Showmanship required insight into human nature and human desires; in other words, it required intuition, a quality particularly associated with women. When the Exhibitor’s Trade Review asked a Belasco executive to define showmanship in 1925, he replied that it was “merely an applied knowledge of the strength and the weakness of human beings—of their likes and dislikes and of certain fundamental ideas that are common to us all.”26“Sebastian Defines True Showmanship,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 11 April 1925, 27. A good example of a female exhibitor using such insight was Theresa Nibler, profiled by the same trade journal in 1919. Having been promoted from box office girl to manager by the owner of the Electric Theatre in Springfield, Missouri, she observed that mothers hesitated to leave expensive baby carriages in the lobby. When she devised a way for women to bring their buggies into the auditorium, ticket sales rose. They rose again when she made an effort to reach farm families through direct mail advertising. She thought up all of her techniques, she said, while selling tickets in the box office and observing customers.27“Theresa Nibler, Graduate from Box Office, Became Manager of the Electric,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 17 May 1919, 1838.

Gender and Exhibition under the Studio System

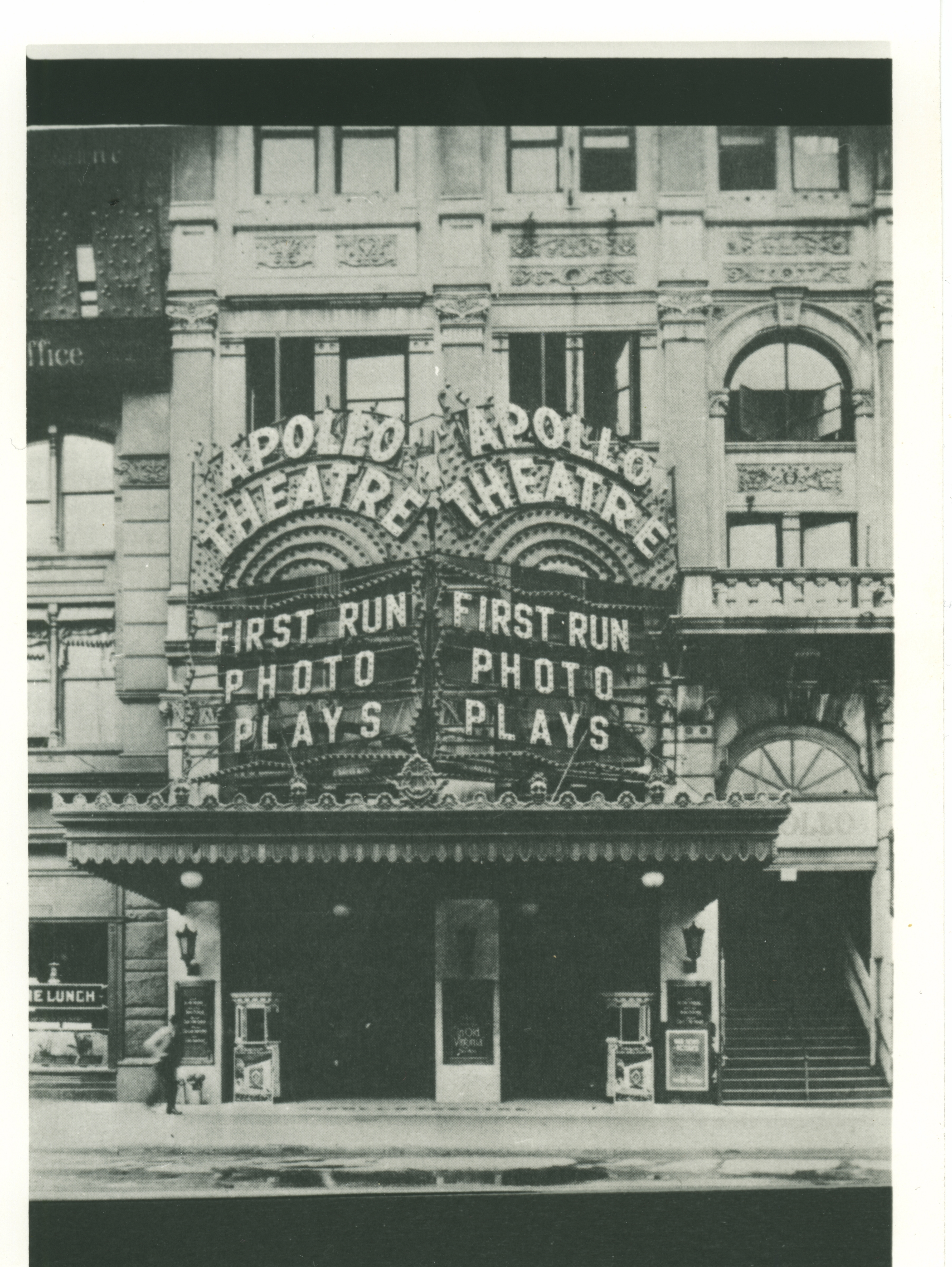

Women remained in exhibition in the 1920s, at which time the film production studios swiftly amassed theatre empires by building ornate urban picture palaces and purchasing established chains. How did this change the landscape for female exhibitors? Three specific questions come to mind: 1) What happened to women who wanted to enter the field when the picture palace upped the ante, requiring much greater outlays of capital, even in smaller towns? 2) Were female exhibitors, and their allegedly moral leadership, rendered obsolete as it became clear that the middle classes embraced the movies? 3) Were women seen as fit for the job of theatre manager as the vertically integrated studios increasingly controlled first-run theatres and attempted to professionalize exhibition on their own terms?

The first question concerns capital and credit. In the early 1910s, when theatres cost between $1,000 and $12,000 to open, the names of female exhibitors appeared in the trade journals with steady frequency. But by the mid-1920s, according to one trade journal, a new theatre cost upwards of $100,000.28“What Should Your Theatre Cost to Build?” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 26 December 1925, 49. Without knowing the exact numbers of women entering exhibition during this period, we can surmise that the most expensive first-run theatres were unlikely to be owned or run by women, as banks generally refused to grant women that level of credit. However, established female exhibitors and women in smaller towns probably experienced fewer obstacles in buying or renting larger theatres. Expansion wasn’t a problem for Ellen Mohrbacher, who ran the Savoy Theatre in a small town in Oklahoma. The twenty-nine-year-old widow, whose first-day-on-the-job speech cowed adolescent audiences into submission, was teaching music when two men approached her in 1921, wishing to sell her one of the only two movie theatres in town. She bought it, and despite an agricultural depression, the theatre did well. She easily gained building loans to expand for sound film in the late 1920s, and to expand again in 1937, in the midst of the Great Depression. Was she unusual? Apparently not; by 1940, women ran about ten percent of the movie theatres in Oklahoma, corresponding roughly to the proportion of women in exhibition during the nickelodeon era.29Pieroth, “The Only Show in Town,” 269.

The second question concerns the fate of the woman exhibitor as an uplifter, since the middle classes wholeheartedly embraced the movies in the 1920s and the censorship threat seemed at bay. Did the female exhibitor bring anything of value to the industry in the 1920s? The answer is yes—but it was no longer morality and the family trade. The time-worn belief in female moral superiority all but vanished in the 1920s, but the belief that women drew the better-heeled did not. This was especially true if the woman herself came from the upper classes. An extreme example of the female-exhibitor-as-high-class magnet occurred when MGM entered exhibition. The expensive, 600-reserved-seat MGM Theatre premiered at Broadway and 46th Street in New York City in 1926. At this event, MGM vice-president Edward J. Bowes introduced the theatre’s manager, Gloria Gould, the 19-year-old granddaughter of (reviled) railroad tycoon Jay Gould. She was appointed to head a staff composed entirely of women. The married Gould had an infant daughter, and, according to the publicity surrounding her appointment, practiced one hour of Russian ballet a week. But it did not sound like Gould’s value stemmed from her ability to spend long hours at the office. According to one account, “Society will be well represented due to the fact that Gloria Gould is the managing directress; screen and stage stars and literary folk as well as civic and national officials will be in attendance. Society matrons and debutantes will act as ushers and program girls on the opening night.”30“Embassy Theater Will Be Watched by Exhibitors,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 29 August 1925, 35, 37.

Gloria Gould’s debut as manager of the MGM Theatre was obviously a publicity stunt. It does not answer our last question: what happened to female exhibitors as exhibition outlets were bought up by the large corporations that comprised the burgeoning studio system? What we find is not surprising. As theatres became part of the new vertically integrated film studios, studio heads imposed a masculinized model of professionalization that rendered obsolete the female-run theatre novelty. This is most clearly demonstrated by the Paramount Publix chain of theatres that sprang onto the scene in the mid-1920s. Publix quickly established a training school for theatre managers. Despite the long history of successful women in theatre administration, its definition of the necessary management qualifications now emphasized masculinized skills and traits. When the Exhibitor’s Trade Review first profiled the school in 1925, students were visiting a factory that produced projectors and learning about the technical intricacies of the various lamps.31“Theatre Managers’ School Visits Nicholas Power Plant,” Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 17 October 1925, 41. Although the era when the exhibitor doubled as projectionist was long over, the Publix school for managers defined this masculinized skill as part of a professional theatre manager’s training. Not surprisingly, photos of the first three classes of theatre managers reveal no women in the ranks, despite the continued emphasis on the need for exhibitors to understand human nature.32John F. Barry, “Theatre Management,” Moving Picture World, 26 March 1927, 325. One reason may be that Publix managers no longer needed to have their finger on the pulse of the local community (women were believed to know intuitively how to reach their neighbors). Within the Publix organization, exploitation ceased to be the sole responsibility of the individual exhibitor. Instead, four former theatre managers ran a central office in charge of advertising and publicity.33Epes W. Sargent, “Exploitation: Its Beginning and Advance,” Moving Picture World, 26 March 1927, 288.

Did this mean that female exhibitors were squeezed out of jobs as movie theatre owners and managers? Our guess is sometimes yes, but mostly no. It is yes with regard to first-run theatres that were tightly controlled by the big, vertically-integrated companies that made up the studio system. It is no with regard to most theatres in the United States—smaller second- and third-run theatres that depended upon local community support. As long as running a neighborhood theatre was a small business—whether independent or franchised—there was room for female proprietors.

Female exhibitors can be compared to their colleagues in film production, who likewise appeared to flourish in the 1910s and disappear in the 1920s. Both occupied rising boats during the film industry’s high tide of emphasis on uplift before World War I, and both suffered when their fields professionalized, because professionalization is implicitly masculinization. But female exhibitors appeared to survive the 1920s much better than did their sisters in film production. This was because the chains of theatres controlled by the major studios did not completely eliminate the smaller neighborhood houses, and the most important factor for the presence of women was the size of the business enterprise.