Although she told several versions of the story, in 1920, Scottish-born Lorna Moon left her job in Minneapolis for Hollywood at the invitation of Cecil B. DeMille after sending him a critique of Male and Female (1920) in which she “razzed him wickedly” for embellishing the original Scottish play (de Mille 1998, 176). She trained with DeMille at Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount Film Corporation for a year then moved on to write three more films for producer Jesse Lasky, two of which were written for Gloria Swanson (de Mille 1998, 178). In 1922, her career was interrupted when she gave birth to screenwriter William de Mille’s son, a baby named Richard whose real parentage was kept secret. Richard was adopted and raised by his uncle Cecil B. DeMille as his own, but in later years all was revealed and the son wrote the biography of Moon, entitled My Secret Mother. Battling tuberculosis for the four years after her son’s birth, Moon wrote short stories and plays from her bed in the sanitarium. In late 1926, she was well enough to return to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where she worked on film scripts for Norma Shearer, Lionel Barrymore, and Lon Chaney. With Frances Marion, she adapted Anna Karenina for a film entitled Love (1927) starring Greta Garbo and John Gilbert. When the tuberculosis again forced her to return to the sanitarium, she completed Dark Star, a novel that reached the best-seller list before her death in 1930.

MGM publicity portrait, Lorna Moon. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library.

Moon was working on adapting a Clara Beranger story for her fourth film, Her Husband’s Trademark (1922), when fatigue forced her to seek a medical examination that not only diagnosed her tuberculosis but confirmed her pregnancy (de Mille 1998, 203). At a time when the Fatty Arbuckle trial and the William Desmond Turner murder were still making headlines, public judgment would have been harsh, and thus cover-up was imperative. As a window into how this was achieved, Moon’s clippings file at the Margaret Herrick Library offers a case study in how to cover up a scandalous pregnancy by means of studio spin. In October 1921, the Morning Telegraph reports that Moon is on “a four month’s tour of foreign countries.” In December it reports that she is “gathering material during her European trip for another original for Gloria Swanson,” and in April 1922, the Morning Telegraph writes that Moon is back after six months of writing short stories in Scotland. In reality Moon was convalescing in Monrovia, just east of Pasadena, in the California tuberculosis sanitarium where baby Richard was born (de Mille 1998, 212). After eight months, William de Mille’s lawyer arranged for Cecil and Constance DeMille to adopt the baby, whom the newspapers reported had been left in the lawyer’s expensive car (de Mille 216). Weakened by the pregnancy and birth, Moon spent another two years in the sanitarium.

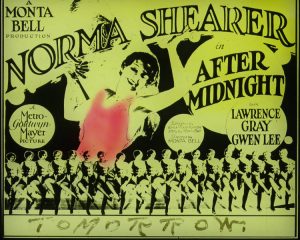

Moon returned to screenwriting at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios in 1926, where she worked in the scenario department with Marion and wrote scripts for Irving Thalberg’s wife Norma Shearer (de Mille 1998, 221). She wrote four films in less than a year, but only After Midnight (1927) has survived. She claimed to have returned to scenario writing only for the money, but by spring 1927, she had to return to the sanitarium and finished the rewrite of Love with a studio secretary typing at her bedside (de Mille 1998, 223).

Lantern slide, After Midnight (1927), Lorna Moon (w). Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery, W. Ward Marsh collection.

Indiana University’s Lilly Library holds the archives of Bobbs-Merrill, the Indianapolis company that published both the novel Dark Star and Moon’s 1925 short story collection Doorways in Drumorty. Richard de Mille augmented the Bobbs-Merrill correspondence and publicity material in 2005 with the Moon Mss., another small collection of Moon’s personal letters. Moon’s letters to Bobbs-Merrill show a writer who swings between confidence and insecurity. In 1928, for example, she writes to her editor, D. L. Chambers, “I’m always either convinced that nobody can write as I can—or that I’m the world’s louseyest [sic] writer.” She complains extensively to Chambers about the demands of the film industry. “The truth is, that when I hired myself to the movie brothel for fifty thousand a year,” she writes in 1926, “I had an optimistic and childlike belief that God was good and that nobody would expect me to do anything for the money. Now I find to my dismay that these sons of Israel expect me to earn it.” Some of the best letters from the Lilly Library are reproduced in Moon’s Collected Works and provide an engaging narrative that details her struggles with Hollywood, writing, and tuberculosis.

Although Moon was able to move back into her house, she never regained enough of her strength to return to the studio. Dark Star was on the best-seller list, but Lorna Moon needed more money in order to try a very expensive new sanitarium in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The story of how Marion and Kate Corbaley tricked the studio executives into paying Lorna Moon seventy-five hundred dollars, while reviving Marie Dressler’s career, should be a legend in the history of female networking in the motion picture business. Marion pitched Dark Star to the male screenwriting team, but instead of telling them Moon’s tragic story, she presented Dark Star as the story of Min and Bill, which was then produced as a comedy from the original script she had written for Dressler (Beauchamp 1997, 264–6).

Richard de Mille’s biography, My Secret Mother, revived interest in Moon and is the most extensive and well-documented exploration of her life and her writing. Since the publication of My Secret Mother, Moon’s work has attracted the attention of literature scholars including Glenda Norquay, who recently edited the Collected Works of Lorna Moon. While this volume returns her novel and stories to print and publishes some of her letters, little attention has been directed to her screenplays. Moon’s complaints about working for the studios suggest that further investigation into the production files may turn up other examples of conflicts that she had with producers or directors. In addition, the complex relationship between Moon and the de Mille family and the way in which the brothers chose to cover up the scandal of her pregnancy suggest how moguls such as Cecil B. DeMille had the power to also write the script of women’s lives.