Contributor Spotlight: WFPP Interview with Joe Yranski

WFPP is delighted to introduce a new series of contributor spotlights, beginning with longtime contributor Joe Yranski.

Yranski, who provided numerous stills for the project prior to our online launch, was the Senior Film and Video Historian at the New York Public Library for over thirty years. He has been involved in film restoration work for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Library of Congress, the Mary Pickford Foundation, NYPL, and Warner Bros., and has contributed to books and documentaries about film history. He acts as an adviser to various silent film series at Film Forum and serves on the executive boards of Cinecon, Syracuse Society of Cinephiles, the New York Film & Video Council, and the Theatre Library Association.

This Q&A, conducted by Megan Heatherly, has been condensed from a two-hour interview and edited for clarity.

Could you tell us a little bit about yourself? Did you grow up in New York?

I’m from Connecticut. I grew up in southern Connecticut, Southport, in the Fairfield area. My family has been there for about seven to nine generations in the same town. But I did most of my education in New York. […] Started at Wagner College, moved to Fordham University, got a double major. Then I went on and got a master’s degree in early childhood […] a library degree from Columbia, Oxford. […] The whole kit and caboodle!

How did you become interested in film?

I was always interested in film, and I had a grandfather who was particularly nice to me, and he would say “Do you want to see a film on Saturday or go to the opera on Saturday?”[…] I was seeing films at MoMA in the fifties, going to Woolsey Hall up at Yale and seeing a lot of nitrate prints that were subsequently destroyed in the late eighties, early nineties.

Why were the prints destroyed?

Nitrates were destroyed because [people] didn’t want to pay for preservation, and they weren’t making money off of them. […] Nitrate is unstable, I won’t deny it. You know that. It can turn to goo, it can turn to dust, it can explode, and the worst part is that it creates its own oxygen. […] When they used to melt down the films, it was for two reasons. Not only to make sure that you weren’t losing the [physical] film, but also to get back the $23.46 of silver that was in that one feature.

In the August 18, 2017 episode of the State of the Arts NYC radio show, you mentioned that previous versions of films would be destroyed once they were remade. Can you tell us more about that?

I have [acquired] contracts from “Colonel” Selig selling a feature film, Garden of Allah, to Joe Schenck in 1920 for a possible remake with Norma Talmadge. It clearly tells you that they destroyed the negative, all known prints except one viewing copy, and they turned over all the publicity material. The reason for [keeping] the viewing copy was so if a scene had to be recreated they would include it, but usually they used alternate types of scenes even if the plot was exactly the same.

What lost film do you wish you could see?

There are so many. The one I would most like to see is an Alfred E. Green production called Sally. It was made in 1925, and it was a silent film version of a musical comedy that played at the Ziegfield Theatre starring Marilyn Miller. Colleen Moore was the star of that version. In 1929, it was recreated as a talkie, and all of the prints were destroyed except for Colleen’s own print, which she gave to MoMA and they allowed it to be destroyed.

What do you like about silent film?

Unlike “talkies”—and I do use that term a lot—silent films are universal. They work just as well in China, Africa, India, and the United States. You just change the title cards. Also, the character types are much more black and white so that you know who is the villain, who is the questionable character. […] I always loved Mary Pickford’s quote, which was, “It would have made more sense if silent films grew out of talkies than the other way around.” Lillian Gish, who was an old friend, always said, “You had the whole world at your feet, and just for talking you went down to ten percent of the world who could understand your films?”

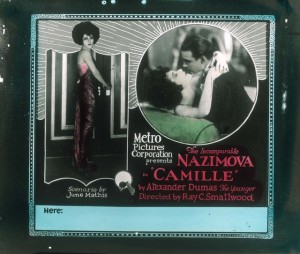

Glass slide advertising Camille (1921), produced by and starring Alla Nazimova, scenario by June Mathis, and art direction/costume design by Natacha Rambova. Courtesy of Joe Yranski.

What made you interested in collecting glass slides and other film media?

I’ve been a collector of other antiques since age twelve, and I swore for years that I was never going to collect film. Around 1980 or 1981, I started to collect stills of Colleen Moore, whom I had known since 1972 and was a good friend. […] Nowadays, I think I have between 20-25,000 stills and 4,000 glass slides. […] I started to collect glass slides because it was easier than doing posters (one sheets, half sheets, etc.) in New York. In New York, even in a five-room apartment, you just don’t have the space.

What’s the weirdest thing that you have in your collection?

I think the weirdest thing is a publicity item for Hotel Imperial (1937). It’s the equivalent of what a hotel key would have been like in the 1920s. It’s a regular key but there is a tag on it that says “Hotel Imperial, Room 222.”

What is your favorite item in your collection?

Well, that’s a little harder to choose. One of my favorites is a piece I was left, and it’s a portrait of Jack Pickford. It’s a pastel, and it hung opposite Mary Pickford’s bed in Pickfair. This was left to a friend of mine who used to be the artistic director of the New Amsterdam Theatre Company.

What are glass slides, exactly?

[The] earlier slides from before 1924 are usually two pieces of glass, much like a glass slide you would have under a microscope. […] Sometimes the later ones will have a cardboard edge so that they don’t break as easily…These things cost, originally, ten or fifteen cents. The way it used to go in the theater […] they would show three glass slides for maybe thirty or forty seconds for coming attractions and then the next would be an actual trailer. […] They [the slides] would usually say “Next Saturday!” or “Thanksgiving Day Weekend!” or something like that.

Do you display your glass slide collection?

I have two light boxes that I built. One is in my bathroom above the commode, so that when men stand they can look at the slides, and in the kitchen, I have a second one. I change them out every three months or so.

Who is your favorite early woman filmmaker?

Lois Weber. […] Suspense from 1913 is probably the best example of split screen in developing emotional content, much better than [D.W.] Griffith or anyone else in her time. And she had a twenty-seven-year career. Most men don’t have ten years, let alone twenty-seven.

What is your favorite Lois Weber film?

My personal favorite is Hypocrites [1915], which was repatriated from Australia/New Zealand about twenty-five years ago by Kino [Lorber].

Why do you enjoy films made by women?

People forget that until 1921 or 1922 […] women were allowed to do practically anything in the film industry […] It’s really amazing, because they have a different perspective and there’s room for all these different types of films. Some of them are very good. Some of them are bad, but what else is new? There are an awful lot of bad films by male directors as well.